Mahatma Gandhi famously argued that Bhagavad Gita needs to be seen as a metaphor of internal war, and has nothing to do with violence. Western scholars argue that the book does the very opposite – it actually promotes violence, and is therefore favoured by Hindutva. To understand this contradictory views, we must revisit the 19th Century, when a poetic retelling of the Bhagavad Gita became very popular in Europe.

Edwin Arnold had composed ‘The Song Celestial’ based on Bhagavad Gita after the success of his book ‘The Light of Asia’, that explained the life of Buddha. Suddenly, two major ideas of India became popular in the intellectual circles of Europe. On one side was Buddha, the pacifist, who wanted to conquer desires and end suffering, and on the other side was Krishna of the Bhagavad Gita, motivating Arjun to fight a war, despite his resistance. At a time when the British were busy following the divide-and-rule policy, and undermining Hinduism, this provided another example of the religion of the Brahmins as a violent oppressive religion, one that wiped out peace-loving Buddhism, and promoted war, an idea endorsed by Babasaheb Ambedkar who opposed Gandhi on many issues.

Everybody finds something in the Bhagavad Gita to suit their politics. In the process, we forget what the problem is to which Krishna offers a solution.

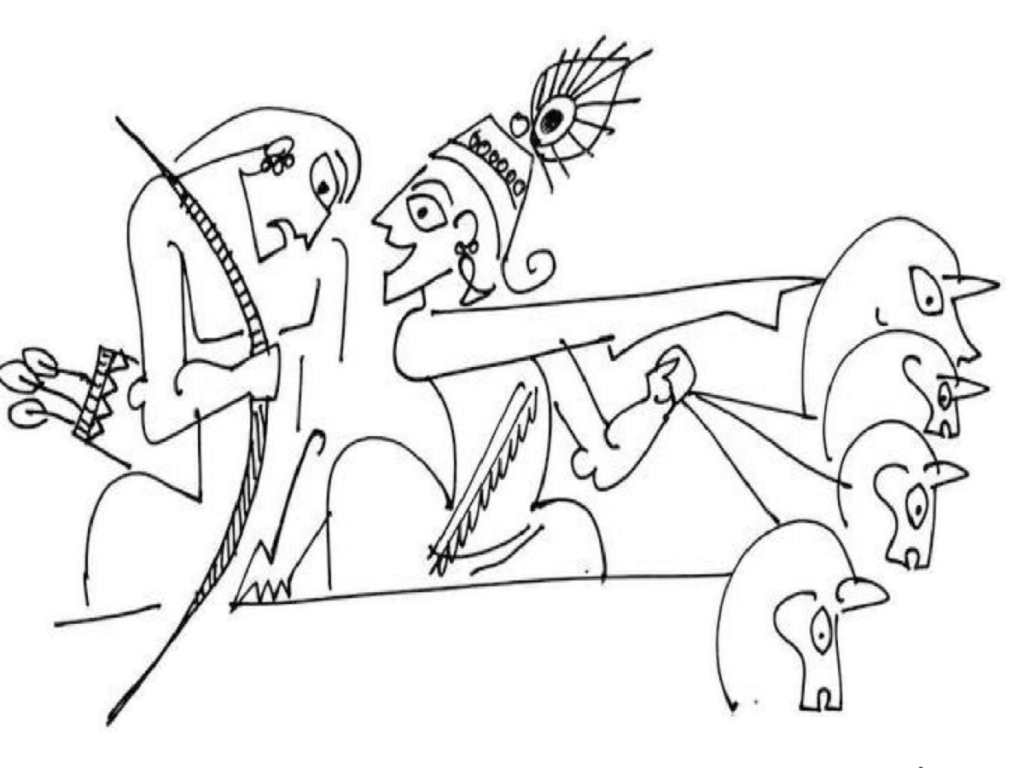

It all starts with Arjun’s issue with the war. His problem is that he does not want to fight a war against his relatives. He has no problem with killing people, he has no problem with war, he has no problem with murdering strangers. He has done so in the past. But, when it comes to fighting relatives – his cousins, his uncles, his teacher – he has an ethical dilemma. Is he not supposed to protect them? How then can he attack them?

This leads us to the key of Bhagavad Gita . Who do you define as relatives and who do you define as strangers? Who do you consider as yours, and who do you consider as not yours? It all revolves around the possessive pronoun: mine. For Kauravas, Pandavas are not family with whom wealth has to be shared; they are strangers, outsiders, trying to claim a share on their property. For Pandavas, Kauravas are cousins who are not sharing family land.

When Krishna becomes the cosmic being in the later chapters, he is effectively says, “I contain every one, thus, all creatures in this world are mine. When all creatures are part of me and everybody is mine, no one is a stranger.” How then does Krishna take sides? On what basis does he support one and oppose another?

Here comes the idea of dharma. Krishna takes sides on the basis of whether the powerful share their wealth with the powerless. The earth belongs to all humans. When powerful humans claim it, at the cost of others, then they are behaving like animals – predators feeding on prey. They are not behaving like humans who can share their food. When humans share wealth, it is dharma. When humans do not share wealth, it is adharma. Krishna supports those who share wealth.

In nature, animals fight over territory. In culture, humans create property. Unlike territory, property can be passed on to children, whether worthy or not. Humans create laws to ensure resources stay within the family, or the extended family – the clan, the tribe, the community, the caste, the religion, the state. To keep wealth within the family, outsiders are demonized. Marriage is not permitted with outsiders so that wealth stays within the family. My wealth thus stays with mine. For Krishna, this nepotism is indulgence of ego, and so adharma. In other words, Krishna’s argument for war, is an argument against hoarding of wealth by the in-group at the cost of the out-group. When humans do not share, war is dharma.

Later in the epic Mahabharata, Pandavas are upset to find Kauravas in Indra’s paradise. And the gods chuckle. Kauravas use material arguments not to share wealth with Pandavas on earth. Pandavas use spiritual arguments not to share heaven with Kauravas. Failure to share results in violence. Non-violence, or violence, that indulges people’s ego is certainly not dharma. This is the lesson of the Mahabharata.

(Devdutt Pattanaik is an Indian mythologist, speaker, illustrator and author, known for his fictional writing on Hindu sacred lore, legends, folklore, fables and parables. Courtesy: Economic Times and Devdutt.com.)