Nearly a third of the 100 cities in the world susceptible to ‘water risk’ — defined as losses from battling droughts to flooding — are in India, according to the WWF Water Risk Filter. This is an online tool, co-developed by the WorldWide Fund for Nature that helps evaluate the severity of risk places faced by graphically illustrating various factors that can contribute to water risk.

Jaipur topped the list of Indian cities, followed by Indore and Thane. Mumbai, Kolkata and Delhi also featured on the list.

The global list includes cities such as Beijing, Jakarta, Johannesburg, Istanbul, Hong Kong, Mecca and Rio de Janeiro. China accounts for almost half the cities.

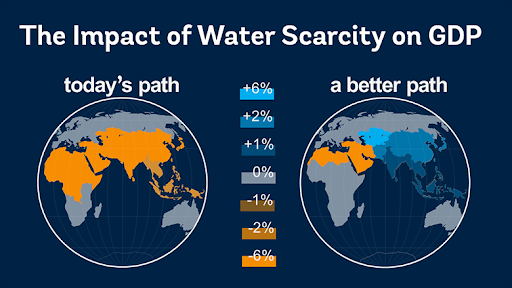

According to the scenarios in the WWF Water Risk Filter, the 100 cities that are expected to suffer the greatest rise in water risk by 2050 are home to at least 350 million people as well as nationally and globally important economies. Globally, populations in areas of high-water risk could rise from 17% in 2020 to 51% by 2050.

‘Restore wetlands’

“The future of India’s environment lies in its cities. As India rapidly urbanises, cities will be at the forefront both for India’s growth and for sustainability. For cities to break away from the current vicious loop of flooding and water scarcity, nature-based solutions like restoration of urban watersheds and wetlands could offer solutions. This is our chance to re-evolve and re-imagine what the future of the cities could be,” Dr. Sejal Worah, programme director, WWF India, said in a statement.

Other than droughts and floods, the city’s risk levels were scored by evaluating several factors, including aridity, freshwater availability, climate change impact, the presence of regulatory laws governing water use, and conflict.

The Smart Cities initiative in India could offer an integrated urban water management framework combining urban planning, ecosystem restoration and wetland conservation for building future- ready, water smart and climate resilient cities. Urban watersheds and wetlands were critical for maintaining the water balance of a city, flood cushioning, micro-climate regulation and protecting its biodiversity, the authors note.

There are many initiatives across the country that could be scaled up where groups have come together and revived wetlands such as Bashettihalli wetland in Bengaluru and the Sirpur Lake in Indore. Urban planning and wetland conservation needed to be integrated to ensure zero loss of freshwater systems in the urban areas, they noted.

(Jacob is a Deputy Science Editor with The Hindu. He writes from New Delhi. Article courtesy: The Hindu.)