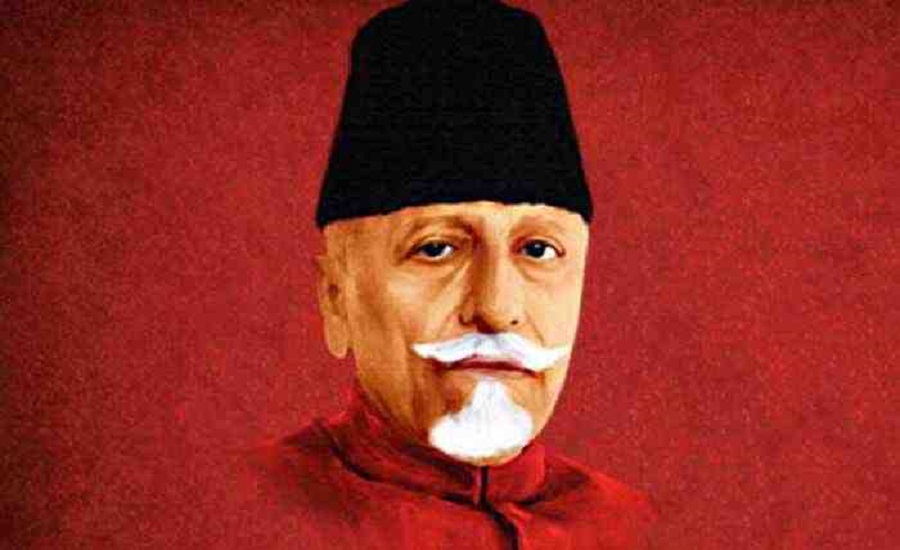

(This article was printed in The Wire last year on 11 November 2019. We are republishing it on the occasion of Maulana Abul Kalam Azad’s birth anniversary.)

November 11 is being celebrated as National Education Day, as it happens to be the birth anniversary of Maulana Abul Kalam Azad, scholar, freedom fighter and the first education minister of independent India. Maulana Azad’s contributions across the fields of education, communal harmony and journalism have been duly recognised, and he was posthumously awarded the Bharat Ratna.

Several books have been written and thousands of seminars and symposiums organised over the years to remember and celebrate his legacy, and rightly so. However, there is one aspect of his life as a freedom fighter that has often been forgotten in all of this, which is how he responded when he was charged with sedition in the year 1922.

This deserves to be remembered and highlighted for at least two reasons. Firstly, not many people know about the case. Usually, when famous sedition trials are discussed, this case does not find a mention. This despite the fact that Mahatma Gandhi, who was himself tried under the law, was highly impressed by Azad’s statement in the case. According to Gandhi, Azad’s 30-page written statement was an eloquent thesis on nationalism.

Secondly, more than any other writing and speech of Azad’s, this best explains his attitude towards the colonial government. This is important to remember because ironically, on the occasion of his birth anniversary today, the Central government-funded and -administered Indian Council of Historical Research (ICHR) is organising a day-long symposium on the life and objectives of Hindutva icon Vinayak Damodar Savarkar, who is often projected as the brave ‘Veer Savarkar’. Savarkar was a known loyalist of the colonial government, contrary to Azad.

Maulana Azad’s written statement before a colonial court in Calcutta is part of an Urdu book titled Qaul e Faisal, parts of which have been produced in A.G. Noorani’s seminal book Indian Political Trials (1775-1947). Azad was tried and arrested in Calcutta in December 1921, under the sedition law, for a few of the speeches he had made in July 1921. He was eventually sentenced for a year’s rigorous imprisonment, which he thought was too light for him.

In defiance of the colonial government, Azad’s written statement (as per Noorani’s book) reads,

“I have been charged with sedition. But allow me, please, to understand the meaning of ‘sedition’. Is sedition a name for freedom struggle which is not successful? If that be so, I would fully agree with it. At the same time, however, I would remind you that its name is also the highly respected ‘patriotism’, once the movement becomes successful.”

He further declared that:

“I believe that liberty is the birthright of every person and every nation… I do not recognise the present government as a legitimate government and consider it my national, religious and personal duty to liberate my country and my nation from its rule…I am a Muslim and it is my duty as a Muslim as well.”

Azad also quoted Prophet Muhammad as saying:

“If you see a wrong being done, prevent and redress it with your hands; if you cannot do that, speak up against it. If you cannot do even that, tell yourself it is wrong. But that is a weaker form of faith (Iman).”

According to Noorani, Azad added that “since people in India lacked the power to set right the wrongs being done by the government, they adopted the second course to which they are entitled, namely to condemn the wrongs.” Azad also said, “I must say that in the last two years, I have done nothing except violate section 124A (sedition).”

Concluding his statement, Azad asked the magistrate to award him the maximum punishment, and without any hesitation. He said:

“I will feel neither aggrieved nor sad. I am concerned with the entire machinery, not with the individual part. I know that unless the machinery is changed, the parts cannot change against their task. The historian is waiting for us and the future has been waiting for us. Allow us to come here often and you may also continue to write your judgments. This will go on for days till the doors of another court are flung open. It will be the court of the law of God. Time will be its judge and will write its judgment. And its verdict will be final.”

Heavily coming down on the role of courts, Azad further said:

“History bears witness that whenever the ruling powers took up arms against truth and justice, the courtrooms served as the most convenient and plausible weapons. The authority of the courts of law is a force which can be used for both justice and injustice. In the hands of a just government, it becomes the best instrument for attaining right and justice. But, for a tyrannical and repressive government, there is no better weapon for wreaking vengeance and perpetrating injustice.”

Listing some of the famous cases of injustices, Azad declared:

“The list of injustices committed by courts is very long. History has not ceased to mourn them to this day. In that list we find a holy person like Jesus Christ, who was made to stand with thieves before a strange court of his times. We find in it socrates who was sentenced to drink a cup of poison for no other reason than that he was the most truthful person in his country. We find also the name of the great martyr to truth of Florence, Galileo, who refused to believe what he knew and learnt from his experiments though their avowal was a crime in the eyes of the court of his time.”

Now, contrast this with Savarkar’s attitude towards the colonial government. It is well documented that unlike Azad’s brave fight against colonial rule, Savarkar, who was sent to the notorious Cellular Jail in the Andamans for his revolutionary activities, petitioned the colonial government for early release within months of beginning his 50-year sentence.

Promising loyalty, Savarkar in his mercy petition wrote in 1913 from Cellular Jail:

“…no man having the good of India and Humanity at heart will blindly step on the thorny paths which in the excited and hopeless situation of India in 1906-1907 beguiled us from the path of peace and progress. Therefore if the government in their manifold beneficence and mercy release me, I for one cannot but be the staunchest advocate of constitutional progress and loyalty to the English government which is the foremost condition of that progress.”

The petitions further read, “The Mighty alone can afford to be merciful and therefore where else can the prodigal son return but to the parental doors of the Government? Hoping your Honour will kindly take into notion these points.”

Savarkar was granted clemency following his persistent petitioning. He was first transferred to a mainland prison in 1921 and finally released in 1924. Upon his release till the independence of India, as per promise, he worked in the interest of colonial power and against the people of India. Moreover, after independence and till his death in February 1966, he helped and worked towards turning independent India into a Hindu rashtra.

Savarkar was also tried for conspiracy as an accused in Gandhi’s assassination. Though the court acquitted him due to lack of evidence, a commission established his guilt posthumously. On the other hand, Azad, for his entire life, worked for the people of India and was one of Gandhi’s most trusted lieutenants in his fight against communalism and injustice. He spent eight years in jail for fighting against British rule.

It is a pity that a prominent governmental institute like ICHR, with its rich legacy, is discussing the life and ideas of Savarkar instead of Azad on his birthday.

(Mahtab Alam is a Delhi based multi-lingual journalist and writer. Article courtesy: The Wire.)