Modi Government Sees Migrant Workers as Mere Labour Resource, Not Human Beings: Some Articles

***

Centre Tried to Charge Migrants to Go Home. Now it is Resorting to Embarrassing Damage Control.

Rohan Venkataramakrishnan

Everything about the Indian government’s policy towards the country’s large, vulnerable population of migrant workers has been a mess.

Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s three-week lockdown was announced with just four hours’ notice, with no thought for their needs, leading to a mass exodus of people setting off for their home villages on foot and cycle. The government’s response was to ask the police to beat them into staying at home, forcing migrants into desperate measures like traveling in a cement mixer.

States ended up forcing them into shelters that were often unsanitary, with horrific facilities and insufficient food. The Centre refused to provide cheap foodgrains to the states, which would have helped universalise India’s food ration system and allow migrants didn’t need ration cards for the states they were stranded in.

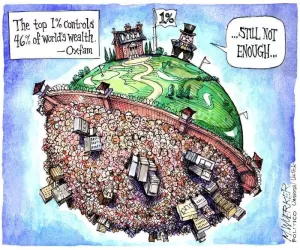

When movement of workers was finally announced, it was clear that the government saw them as labour resources, not human beings and citizens with desires, since they were only permitted to move to go to work, and not go home.

And now, five weeks after the lockdown, with the government finally permitting movement for a limited set of stranded migrants, it wants to charge them money to do so.

Special trains and buses were organised for the movement of those stranded, but the Indian Railways made it very clear in a May 2 order that the tickets would be printed and handed to state governments, which would then collect the ticket fare from the passengers and hand this to the Railways.

This naturally turned into a political controversy, since it seemed heartless for the Indian state – after all it had put migrants through, coupled with the fact that in almost all cases they had been left without wages and often with unpaid arrears – to charge them for a journey home.

Congress President Sonia Gandhi said that the party would collect funds to pay for all the migrants, a move echoed by other parties like the Rashtriya Janata Dal, prompting a day of political squabbling, with the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party forced into damage control.

Later in the day the BJP and the government attempted to claim that the fault was of the states, and Congress ones in particular, because the Centre was paying for 85% of the fare, and asking the state government to contribute just 15%. It also claimed that Congress states were the only ones charging migrant workers for travel.

All of this is untrue.

First, the Centre is not paying 85% of the fare. There is no order to that effect anywhere. Though it is unclear why he spoke about this, Lav Agarwal, the joint secretary, health, told reporters on Monday that the Centre was paying for 85% of the cost – not the fare – while states were paying for 15%. BJP National General Secretary attempted to explain this.

What is the difference? Indian railway fares are always subsidised to keep ticket prices low. The Centre wants to claim that paying this subsidy amounts to covering 85% of the cost, while it asked the states to collect the remaining amount – in other words, the full fare including an extra cost for taking fewer passengers because of physical distancing – from the workers.

Remember here that inter-state travel is a Central subject. All of this, from the organisation of travel to the cost, should have been sorted out by the Centre.

Next comes the claim that it only wanted states to pay the full fare, which it calls the remaining 15%, not the migrants. Yet the May 2 order belies that. And it claimed that only Congress states were passing this cost onto to the migrants.

The actual experience of workers taking trains in BJP states makes it clear that this is false. Workers taking a train from Gujarat (a BJP state) to Uttar Pradesh (a BJP state) told the Ahmedabad Mirror that they had to borrow money to be able to pay for the tickets. An Indian Express report from Gujarat reiterates this point.

Some state governments did say that they would cover the fares, but the Express reported that Jharkhand, Chhattisgarh and Rajasthan had decided to do this – none of them BJP states.

Clearly, the claims of the BJP and the government were entirely untrue. The Centre had wanted to charge labourers for the return journey. But the amounts would have been a pittance to the Centre, even in Covid-19 times. So why would it possibly have taken such a callous step?

One answer comes from Karnataka, where workers were also being asked to pay for state buses to go home.

“If we provide free transport, everyone will return home, creating problems both in the villages – triggering fear of spread of Covid-19 – and here in the city, hampering revival of economic activity, including construction work,” a senior Karnataka official told The Hindu. “As we are charging them, only those who genuinely need to go home will go.”

If this logic is the same that applied to the Centre’s decision on charging train fares, it appears to be yet another instance of utilitarian policymaking – thinking of migrant workers as nothing but resources to be saved in the city, even if their desire is to go home. This has been exposed by the current controversy, and now the BJP is engaging in an ugly, embarassing effort at backtracking to avoid the political fallout.

(Courtesy: Scroll.in.)

***

Jean Dreze, in an interview to G.S. Vasu, “Keeping Migrant Workers from Returning Home Will Deepen COVID-19 Financial Crisis”, adds:

G.S.V.: There has been a lot of debate over migrant workers, as a majority have gone back to their respective towns and villages. But even those who have remained in the cities would like to go back the moment they are in a position to do so. There is this concern that a good number of them are unlikely to come back. In such a scenario, what do you think is going to happen?

J.D.: I think the situation and impact is going to be even worse in poorer states like Jharkhand and Bihar where people are now returning because what is going to happen now is that people are going to be afraid of resuming migration for sometime, certainly as long as there are any lockdowns anywhere.

As you pointed out, there is going to be a labour shortage in some states, like Punjab, Gujarat, Maharashtra and so on, but more importantly, it is going to create a huge surplus of labour in places like Jharkhand and Bihar and this is going to create a crisis of livelihood because the wages are going to be under stress and the earnings are going to come down and people will have to fall back on survival activities.

I think the longer we hold them captive and prevent them from moving back, the more is going to be their reluctance to migrate again later on, and more serious is going to be the economic crisis. And this goes for both the labour-short states and the labour-surplus states.

And I have a feeling that one reason why there is so much of reluctance to let them go is not so much the fear of the virus spreading but the reluctance of the employers in these states, who are employing these migrant workers, to let them go because that is their source of cheap manpower.

G.S.V.: Are there any specific areas where employment opportunities could be created for these migrants in their hometowns?

J.D.: I think that the obvious potential is in the Rural Employment Guarantee Act. In fact, here in Latehar, so many people are asking for MGNREGA employment under the Rural Employment Guarantee Act because they have nothing to do. They have been sitting around for weeks and they know that it may last for quite a bit longer. So, naturally, they feel it is better to work on the National Rural Employment Guarantee Act and earn something, even if it is not very much, rather than continue doing nothing. There is a huge potential there, it is actually a very important opportunity to revise the NREGA.

Of course, there will have to be some safeguards like maintaining distance at the worksite but I think that can be done.

G.S.V.: There are two independent datasets that are emerging — one from the World Food Programme which states that a further 130 million people could face acute hunger this year. The other is that of the ILO which says that 40 crore workers in India are likely to be pushed into poverty because of this pandemic. Any sense of the numbers and is there anything that we could do to alleviate this crisis?

J.D.: Well, I think these numbers are a little speculative because, obviously, we don’t know how long this lockdown is going to last and even the baseline figures about poverty and hunger are not really reliable. The latest poverty estimates in India go back to 2011-12. What I can say is that these figures are plausible. For example, when you say that 130 million people could face hunger this year, if you remember that about 500 million people in India live in households that don’t have a ration card, we are basically saying that one-fourth of these households may be exposed to hunger in the next few months. And I think that’s quite a reasonable hypothesis.

I think we must also remember that there is one important group of people who may face hunger in the near future, and may already be facing it now, and that is the elderly. It is always the elderly who are the most neglected and that is more than 100 million people in India. So, we are basically talking of very large numbers, whether it is exactly 130 million or more or less, we can’t really say but it is in that range that we are talking about.

G.S.V.: While some are advocating direct cash transfers, you have been emphasising the need for food transfers over the next few months. Can you elaborate on that?

J.D.: I think most people recognise that we need both food transfers and cash transfers in this situation. It is very important to realise that right now, it is the food transfers, especially the public distribution system, that are keeping millions alive and secure from hunger. In the district where I am right now, in Latehar, Jharkhand, you can see very clearly, everywhere you go, that people depend crucially on the public distribution system to feed their families.

On food transfers, I feel more needs to be done. I feel that the central government should be releasing much more food grains — it has enormous stocks of food grains from what I have understood — and it is not clear why they are not releasing more. For example, recently, the Jharkhand government sent a request for a very modest amount of extra food grains so that more people could be covered under the public distribution system and that was refused.

I think we need more food grains to universalise the PDS, if possible, at least in rural areas and urban slums and also have, on top of that, emergency food distribution programmes like community kitchens or distribution to migrant workers in addition to the public distribution system.

G.S.V.: While you have clarity on the situation in Jharkhand, are you getting inputs from other states in regards to the food distribution programme — how efficiently it’s happening or otherwise?

J.D.: Obviously, the public distribution system is not perfect but you know, Jharkhand has been one of the worst for a long time and it is actually now working reasonably well. However, the main problem is that many households still don’t have a ration card but those that do are now getting double rations. And even though, it’s not working perfectly, it does work sufficiently well to ensure that a large part of the population is protected from hunger.

In many other states, there are better public distribution systems including neighbouring states like Odisha and Chhattisgarh that are very poor. I think that it can be improved a lot more but it works sufficiently well to be the primary source of security for a very large part of the population at the moment.

G.S.V.: Isn’t it time that we do away with ration cards? Can’t it be distributed based on, say, Aadhaar?

J.D.: No, on the contrary, I think it is the time to realise what an important asset for the country the public distribution system is and that is not to say that cash transfers are not necessary, I think they are also necessary, but the public distribution system has the advantage that it is right there and it is in place — there are ration shops in almost all villages. In this situation, it was very easy to activate because it was already in place.

I think, ideally, I would like ration cards to be given to every household, at least temporary ration cards for one or two years in this situation. Of course, it is true that to do that you may need one or two months and in that interim emergency period, you may have to distribute food to people who don’t have ration cards. What you need is not so much a ration card, what you need is a list of people to whom you are giving food. Once you have that list, I wouldn’t even say Aadhaar, I would say give it to them irrespective of whatever ID they come up with or even no ID, as long as you know who you are giving food to.

And in the immediate emergency, like the migrant workers who have nowhere to go, there are situations where you may not want to insist on any ID. But that’s an emergency situation, you cannot run the PDS like this for a year or two. We should be taking a slightly longer view, then it is better to give ration cards to everybody and universalise the PDS. That is a much more effective and rational approach.

G.S.V.: One of the flaws that has come out quite starkly in the wake of the virus spread is in the public health system in the country. What do you think needs to be done to put it back on track?

J.D.: I think the entire healthcare system needs to be rethought, it has been neglected for decades — that is a quite well-known issue. It is a very prioritised healthcare system, basically based on profit and also very poorly regulated and I think it is well understood in economics that the profit-driven healthcare system is very ineffective as well as being inequitable.

Ideally, there should be no profit-making in the field of healthcare — that may not be easy to achieve — but I think the basic principle of the healthcare system should be what is called ‘universal healthcare’. In other words, everybody should have the right to healthcare in a situation of illness. This does not mean that private healthcare will disappear, some people may still prefer to use the private health facility that is available but it does mean that the system has to be planned for the public good and not for profit and that is where there is a real gap in India because the system is mostly profit-driven. Other countries have done it at a time when they were not much richer than India. In fact, Thailand, which has a very impressive healthcare system based on the principle of universal healthcare, put that system in place around 2001-02 when its per capita GDP was not much higher than it is in India today. So, if Thailand could do that 20 years ago, I think India could do something similar today.

G.S.V.: Can you specify three major failures and three steps that need to be taken in the light of the experiences now and post the virus?

J.D.: Other than healthcare, I think, one of the big lessons of past development policies of India is the lack of attention to human resources through education, training, healthcare and social security. And one reason why Kerala is doing so much better than most other states at the moment is that it has developed human resources. So, it is much better equipped to face the crisis and involve people in fighting the virus.

Then comes social security. The fact that we have a PDS in place is helping us a great deal in this crisis to avoid hunger and starvation. And similarly, if we had a better-developed system of social security in general, including social security pensions, better functioning of the Employment Guarantee Act, maternity benefits and so on, it would have been much easier to go through this crisis and avoid the kind of humanitarian disaster that is happening at the moment with this lockdown.

(Jean Dreze is a noted economist, author and social activist; G.S Vasu is The New Indian Express Editor.)

***

Below are extracts from two more articles related to this issue:

‘Republic of Hunger’ in the Time of ‘Lockdown’

Shashi Kant Tripathi

As per the Global Hunger Report 2019, India’s position in the index is 102 out of 117 countries. Neighbouring Pakistan and Bangladesh are better than India in this index. The portion of undernourished in the population is 14.5 percent. 37.9 percent children under five years are stunted and 20.8 percent children under 5 year are wasted. Another serious food related issue is anaemia. More than 50 percent of women and children are struggling with anaemia. Another study regarding diet related deaths by Lancet shows 310 deaths per one lakh in 2017. In 2016, 28.1 percent of the total deaths are caused by cardiovascular diseases. Cardiovascular disease is one of the leading cause for deaths due to lack of a complete diet. According to the National Sample Survey, 68 percent population of rural India are not able to access 2200 calories (benchmark nutritional norms to define poverty) in 2011-12 and 65 percent of the urban population are not able to consume 2100 calories in same year. This data shows that India’s condition is bad as it is and that lockdown will only worsen the health condition of people further.

Availability of food is another pertinent problem in India. Per person food absorption has been declining slowly after economic reforms in the country. Data of the Ministry of Agriculture and Family welfare shows that the net availability of food grains per person per year was 177.9 kg in 2016 while 186.2 percent in 1991. While, in 2015, China and Bangladesh’s food availability per capita were 450 kg and 200 kg respectively. This picture is alarming for healthcare in India. Utsa Patnaik, in her article “The Republic of Hunger” (2004), stated that “this country was once a developing economy, but which has been turned into the Republic of Hunger.”

The stock of foodgrains in central pool till December 2019 was 564 metric tons. This highlights the incompetency and more importantly, a lack of will of the government to not distribute available food grains to its population. As Jean Dreze writes, “how would you feel if a family were to let its weakest members starve, even as the House’s granary is full to the brim.” He stressed the need for the central government to unlock the godowns and supply food to the States. Although there are some measures like food distribution by state governments, disbursal of Rs. 500 to 4.07 crore women as ‘ex-gratia’ in PMJDY account holders, these are not sufficient to tackle the hunger related problems….

For the sake of saying, the virus does not discriminate between people, but in reality, it does. To begin with, it was a rich man’s disease that has now been passed on to the poor who lack the strength to fight it, both physically, and financially. People who are daily wage labourers and barely manage two square meals a day are incapable of stocking ration and supplies so that they can sit at home and practice social distancing norms (most of them, not ironically, do not even have homes).

A decent life is a fundamental right of the people. But the government is leaving the masses to think that even ‘survival’ is a privilege. If India doesn’t want to label the death of these workers as ‘collateral damage’, the government must ensure universal nutritious food for all and also ensure minimum income for majority whereby people can purchase non-food essentials. Only ‘cards’ based ration cannot solve the problem of hunger in India. What is urgently required is the politicisation of the issue of hunger, otherwise, through neglect and unsound policies, the government will lead large sections of its own population to death.

(Shashi Kant Tripathi is Research Scholar at Jawaharlal Nehru University.)

Ethanol and Hunger in India

K P Sasi, 22 April 2020

With more than 200 million hungry people, India is the home to the largest number of hungry people in the world. More than 190 million people in India sleep without food daily. One out of 4 to 5 children in India is malnourished. Malnourished people are prone to different diseases much more easily than the nourished lot. Needless to say that this population of hungry people in India can be seen as the most threatened section due to COVID -19. While the number of deaths and suicides due to the lockdown is increasing among the poor in India, the real figures of indirect deaths due to the lockdown are either not estimated properly or not being reported properly. But our Government has come out with a beautiful solution to India’s hunger. Since there is a contrast between overfilled stock of grains in India, this stock of surplus food grain is going to be used for the production of ethanol to produce sanitizers to fight COVID-19! Let the hungry people in this country feed themselves on ethanol at least !

(K.P. Sasi is a film maker, cartoonist and writer.)