Indian Government Bonds Added to JP Morgan Emerging Markets Index:

Who Loses, Who Gains?

1. Indian government bonds are added to the JP Morgan Emerging Markets index

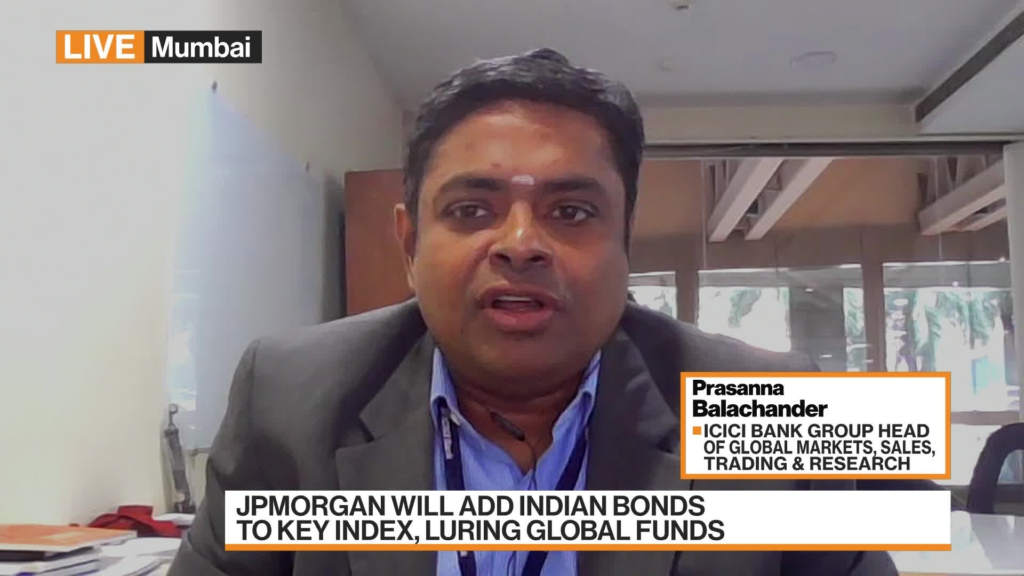

Almost two years ago, we wrote a note pointing to the strenuous efforts the Indian rulers were making to get Indian government bonds added to international bond indices. After two years of stalling and starting, the rulers’ efforts have finally succeeded: JP Morgan has now decided to add Indian government bonds to its “emerging markets government bond index” (GBI-EM), starting in June 2024.[1] The effects of this will be seen with a lag, over the next few years, but the impact will be far-reaching.

What are bond indices? International investors invest in baskets of government bonds of different countries. These baskets, or indices, are constructed by certain giant financial firms in the developed world, who certify that the bonds are stable, plentiful, and easily traded; and that each country’s economic policies make it creditworthy. Once a country’s government bonds are added to such an index, a certain amount of foreign investment would tend to automatically flow into its bonds.

There is much celebration about ‘index inclusion’ among financial circles and in the media. Hence we repeat below some points from our earlier note on this topic. For, when we examine who benefits from this, and who loses, that tells us much about the actual class basis of the present policies.

“We require flow of capital”

The groundwork for this development was laid more than three years ago. In her 2020-21 Union Budget speech, the Finance Minister declared that India would open up to foreign investment in Government bonds, saying, “To achieve the aspirational growth rate, we would require flow of capital in our financial system.” Accordingly, on March 30, 2020, at the height of the first Covid lockdown, the Reserve Bank of India removed the limits on foreign investors’ purchases of certain categories of Government bonds; these were now called the ‘Fully Accessible Route’ (FAR).

Following this, the RBI to date has made available bonds with a value of $417 billion[2] under the FAR, in which foreign investors may invest without limit. However, foreign investors as yet own less than 3 per cent of the total value of FAR bonds. Now, with JP Morgan’s inclusion of India, commentators expect sizeable inflows of foreign investment into Indian government bonds, in the range of $20 billion a year by mid-2025; some financial analysts see this rising eventually to as much as $50 billion a year if certain other international financial firms too include India in their indices.

The authorities are pleased. V. Anantha Nageswaran, Chief Economic Advisor (CEA), portrays this as a sign of India’s growing strength: “We welcome this development. JP Morgan has made this decision on their own. It attests to the confidence that financial market participants and financial markets, in general, have in India’s potential and growth prospects and its macroeconomic and fiscal policies.” Large financial firms too gush praise. These inflows, we are told, will raise demand for government bonds and thus bring down interest rates, both for the Government and for the private corporate sector.

The CEA even claims that these inflows could be a source of funding for the current account deficit. (A current account deficit takes place when India’s foreign exchange earnings over, say, a year are not enough to pay for its foreign exchange expenditures. In that case, the deficit is met from capital inflows – by borrowing abroad, or getting foreign investment, or selling some of the RBI’s foreign holdings. Increased foreign investment in Government bonds would merely add to such inflows.)

Illusory gains

In our earlier piece, we had argued that:

- the claimed benefits of such investment are illusory, indeed India will incur net costs;

- the additional capital inflows would merely flow in and out of our system, without boosting the domestic economy;

- the risks of volatility – i.e., of large movements of capital in and out of the country – are grave; and

- even if the risks do not materialise, the country would be subject to a fiscal-financial regime of still greater obedience to the demands and strictures of foreign investors, requiring setting aside the needs of the domestic economy.

Today, all these points are borne out by the statements of the very persons who are celebrating the inclusion of India in the JP Morgan index.

Before proceeding, we need to remind ourselves of an elementary fact: when foreigners invest in Indian government bonds, they are not handing over money to the Indian government for free. Such inflows are an addition to India’s existing foreign debt, and a corresponding reduction of its domestic debt. While it is true that the foreign investors will be paid in rupees, they will convert those rupees into foreign currency and remit their earnings abroad. Thus, rather than declaring that “India could get $25 bn inflows”, newspaper headlines should have read “India could add an additional $25 bn a year to its foreign debt”.

The immediate trigger for index inclusion was that, due to the war in Ukraine, Russian government bonds have been removed from the global indices of JP Morgan, Bloomberg and other such western firms. So index providers needed another country’s bonds to fill the gap. And this in a period when many ‘emerging markets’ are already facing debt crises. India, ‘default-free’ and with large foreign exchange reserves, thus becomes a relatively stable and profitable opportunity for international investors. In this way, both push and pull factors played a role in India’s index inclusion.

Now let us turn to the statements of the authorities and the experts.

(i) Interest rates

While they claim that the increased inflows would reduce interest rates on government debt, the reduction in rates they actually project is small.[3] The CEA himself was careful to avoid predicting how much government borrowing costs would go down, noting that the interest cost of Government borrowing was already under control. He tentatively suggested that with the additional inflows “It might come down somewhat even further”.[4]

At any rate, such talk – of reducing borrowing costs through opening up to foreign investors in debt – is a red herring. It is not necessary to open the country to such flows merely in order to reduce borrowing costs; that can be done by a decision of the RBI to lower the interest rate at which it lends to banks, and/or by the RBI itself purchasing Government bonds. The problem is that the authorities are wedded to neoliberal economics, which believes in restricting Government borrowings and Government intervention generally, and advocates freedom for finance.

(ii) Volatility

Economists at private Indian banks admit that the inclusion of India in global indices will mean more volatility.[5] It is well established that volatile capital flows destabilise countries’ economies. Even the International Monetary Fund, which has been the principal proponent of opening up the capital accounts of countries to such flows, has been forced to admit the dangers of such volatility, and to repeatedly (though inadequately) revise its “institutional view” over the past two decades.[6] Recently, a former deputy governor of the RBI, also India’s former Executive Director at the IMF, warned in an op-ed article: “[India] should be particularly careful in opening the capital account, especially to volatile debt inflows into its bond market.”[7] (emphasis in the original) When the going is good, surges take place, which in turn attract speculators known as ‘bond market tourists’. When, however, there is a downturn, or when there is a change in the global economy, these ‘tourists’ depart with their cash, deepening the host-country crisis.

The inflows into India bond market may be small at first, but they could rise over time. Once foreign investors’ share in Indian government bonds rises to over, say, 10 per cent, any move by them would have a sizeable impact on not only the Government bond market but the value of the rupee. India’s Chief Economic Adviser himself acknowledges that

foreign holdings could introduce volatility in the Indian bond market or currency during times of global uncertainty, even if these fluctuations were unrelated to Indian macroeconomic fundamentals…. it was inevitable that external events causing financial market volatility worldwide would affect India’s government securities (G-sec) yields and currency…. Investors will be reacting to global developments in their portfolios and adjust their exposure to the Indian market accordingly. Such responses are to be expected (emphasis added).[8]

That means that interest rates in India may not only go down in the new regime, but also at times go up. This may happen if, say, interest rates are hiked in the US, or if any global crisis leads to capital flying out of countries like India. We have already been familiar with such volatility, ever since India opened its share market to foreign financial investors. Now, by opening its Government bond market as well, the volatility could be doubled.

Nevertheless, the prospect of India being made even more subject to fluctuations in the global economy does not deter the CEA, who says: “We are used to handling volatility. Our central bank is well-experienced in managing currency and interest-rate volatility.” He does not mention that managing volatility has a cost, which would more than cancel out the claimed interest-rate benefit.

For example, if there is too large an influx of dollars (or euros, yen, etc), the rupee’s value would rise. When the rupee’s value rises, it renders imports cheaper in rupee terms (displacing domestic production), and India’s exports become uncompetitive abroad. This loss of domestic and foreign markets for Indian producers depresses India’s economy. Nageswaran admits this is a potential problem, and says that the authorities would have to “ensure that the rupee remains competitive.”[9] That is, the RBI would step in and buy up the incoming dollars, giving rupees in exchange. However, this pumping out of rupees can in turn lead to an unplanned growth in the domestic money supply. In order to mop up the excess rupees, the RBI would then have to issue ‘monetary sterilisation bonds’. When investors buy these bonds, the excess money supply would get removed from circulation (‘sterilised’), but at a cost: the RBI would have to pay interest on these bonds – which the Government would in turn provide from its Budget. Ultimately, then, the ordinary public winds up paying for the costs of managing currency volatility. All this has actually happened earlier with surges of inflows of foreign investment in the 2000s.

(iii) Net drain

But there is another cost staring us in the face: the gap (‘spread’) between what we pay out on such debt, and what we earn on our foreign investments.

The CEA deceptively suggests that additional inflows could fund the current account deficit, but he does not mention a simple fact, of which he is perfectly aware: namely, that the existing large capital inflows already fund the current account deficit. Indeed, these inflows have consistently been so large, and so much in excess of the current account deficit, that the RBI is forced to buy up the excess inflows and store them in its foreign exchange reserves. In the specific years in which inflows do not fully cover the Current Account Deficit, the reserves are drawn down to cover the gap. But such years are few and far between, and the gaps to be covered are small in relation to the reserves.

The RBI’s foreign exchange reserves are not kept as notes in a trunk in the RBI. They are invested abroad by the RBI, in safe investments such as US government bonds. While such flows help sustain the US economy, they do nothing to help the Indian economy or achieve its “aspirational growth rate”. Since the inflows are consistently larger than the current account deficit, the foreign exchange reserves have kept piling up, year after year, with only small dips along the way, as can be seen from Chart 1 below.

The size of these reserves is a matter of pride for the rulers, who flaunt them as a sign of the strength of the Indian economy. But the reverse is true. India’s reserves are not accumulated from trade surpluses, as is the case with China, Saudi Arabia or Germany. They are accumulated from capital inflows, which we owe to foreigners. Side by side with piling up foreign assets, India has been piling up foreign liabilities every year. Indeed India’s foreign liabilities are 40 per cent larger than its foreign assets.[10]

Since the interest rate the RBI gets on its foreign currency assets is lower than the interest rate paid out on Indian government bonds, the entire operation in fact acts as a drain. For the year 2022-23, the RBI earned a 3.73 per cent return on its foreign assets,[11] a sharp improvement on the earlier year, thanks to the US raising its interest rates steeply last year. However, foreign investors’ returns on their investments in India are still multiples of that. By soliciting more inflows, and then parking these inflows abroad in the form of foreign exchange reserves, the rulers are merely stepping up the drain.

(iv) The regime of monitoring

Since India’s international liabilities were conservatively estimated at $1.27 trillion in March 2023, much of which can be withdrawn from India at short notice, India’s rulers pay close attention to the views of international capital, and tailor their fiscal and other policies accordingly. That is why the Indian government gets so upset about the way in which international credit ratings agencies (Moody’s, Standard and Poor) set its credit rating; a recent Economic Survey devoted a whole chapter to complaining about their unfairness.[12] That is, India’s economic policy is already under a regime of monitoring by international capital.

Now, with sizeable inflows projected to come into Government bonds in coming years, there will be a much tighter regime. After the JP Morgan index inclusion, the CEA “stressed that India’s fiscal and monetary policies would need to be cognizant of global perceptions and sensitivities”.[13] Those on the financial markets are well aware of this. Jehangir Aziz, head of JP Morgan Emerging Market Economics Research, says candidly that “finally you’ll have a set of investors who can actually move out of Indian bonds, if, for example, fiscal discipline isn’t maintained. So this is the first time I think you’re… going to get market discipline on the government, which we never had.”[14] (emphasis added)

India’s Finance Secretary says that JP Morgan’s step “is being done on their own, and is not based on Government action”, blithely ignoring the fact that it is precisely a response to Government action, namely, opening up Indian government bonds to foreign investment without limit. At the same time, he says revealingly that the JP Morgan decision is a “reflection of the record of (the Government’s) fiscal prudence.”[15]

2. The effect of the fiscal policies demanded by foreign investors

Indeed, the Government’s recent fiscal policy can be understood better precisely in this light: it has been grooming itself for index inclusion for some years.

One should keep in mind that the Indian economy is normally marked by a paucity of demand. The booms that it has witnessed from time to time have been the result of special factors, such as rapid inflows of foreign speculative capital for brief spells. The benefits of these booms are restricted largely to a small section, and they eventually collapse, to be followed by long spells of stagnation or depression. The reasons for this condition are to be found in the country’s underlying political economy. Within this overall frame, the rulers’ drive to groom the economy according to the wishes of foreign investors has the effect of further depressing demand.

Over the last two years, the Central Government has been on a drive of fiscal retrenchment, bringing down its fiscal deficit/GDP ratio each year even though the economy has not yet recovered from the Covid lockdowns, let alone earlier blows such as demonetisation and GST. So aggressive is the present fiscal retrenchment that, in 2023-24, the Central Government’s total expenditure is set to shrink as a ratio of GDP.

Within this, the Centre is in particular driving down ‘Revenue Expenditure’, i.e., the recurring expenditure which includes items such as salaries, welfare, and subsidies, and which thus adds directly to purchasing power in the hands of people. The Centre’s Revenue Expenditure (excluding interest payments) has fallen as a ratio of GDP for the last two years. This year, it is set to fall from 9.3 per cent of GDP to just 8 per cent (see Chart 2 below). In fact, this year, Revenue Expenditure (excluding interest payments) is budgeted to fall by 3.8 per cent even in nominal rupee terms; after assuming inflation at 6 per cent, the cut would come to 9.3 per cent in real terms.[16]

As a result of this regime of spending restraint, the percentage of the Central Budget spent on the basic needs of the people has declined. The budgeted figure for health, rural employment, social assistance, anganwadis, midday meals, and maternity benefits in the Central Budget of 2023-24 is Rs 1.2 lakh crore lower than the ‘Actuals’ figure for two years earlier, i.e., 2021-22. That is a drop of 26 per cent in nominal terms; the real drop, after taking into account inflation in the intervening two years, would be even greater.[17]

Deepening the depression

Note that this so-called “fiscal prudence”, which has won the hearts of JP Morgan and other international speculators, has deepened the depression of the economy.

Both rural and urban real wages have been on a downward trend for some time now. This is not only the conclusion of economists critical of the Government, such as Jean Dreze and Himanshu.[18] It is now also the finding of two official documents, one of the Finance Ministry, and the other of the RBI.

The Finance Ministry’s Economic Survey 2022-23 admits that real rural wages, i.e. after discounting for inflation, have been falling. This can be seen most strikingly in the real wages of men in non-agricultural occupations (see Charts 3 & 4 below). The RBI’s Financial Stability Report of June 2023 reports that real wages in both rural and urban areas are “stagnant”; indeed, they are declining (see Charts 5 & 6).

How dire is the employment situation can be seen from the steep rise in demand for MGNREGS work. As can be seen from Chart 7, the demand for such work is now consistently higher than four years earlier. In April-September 2023, the monthly average of households demanding employment was 27 per cent more than in April-September 2019. It should be kept in mind that MGNREGS work is at below-market wages (the average wage rate in the current year is Rs 238/day).

A recent study by the National Council for Applied Economic Research (NCAER) finds that the real incomes of food delivery platform workers – i.e., after discounting for inflation – have fallen steadily. Moreover, their fuel costs have risen steeply. After deducting fuel costs, their real net incomes declined between 2019 and 2022 by 24 per cent (see Chart 8 below).[19] (Note: These calculations do not take into account the capital costs of these workers, in the form of smart phones, two-wheelers and kit bags.)

Note: The figures above are after (1) subtracting fuel costs, and (2) deflating using the Consumer Price Index 2011-12. The data are of long-shift food delivery platform workers. Source: NCAER.

Nor is the effect of the general depression of demand restricted to wage workers. It has also had an effect on farmers’ terms of trade, which have deteriorated during 2021 and 2022, as can be seen from Chart 9 below. (More recent data are not yet available.)

Shrinking consumption by labouring people

As a result of this outright decline in the incomes of workers and peasants, their consumption has shrunk in absolute terms. In the absence of timely survey data in this regard, sales by fast-moving consumer goods (FMCG) companies (which are in large measure items of mass consumption) do give us some idea of the consumption of working people. The market research firm NielsenIQ finds that the total volume of FMCG sales has not grown at all in the last two years, and the volume of rural sales has shrunk at the compound rate of 4 per cent a year (see Chart 10 below).

With depressed incomes, workers and peasants are forced to cut back even further on their purchases of durable goods. The sales of two-wheelers have not yet recovered to their pre-pandemic levels (see Chart 11).

The RBI carries out Surveys of Consumer Confidence every two months. Those surveyed express whether, in respect of employment, prices, income, spending (essential and non-essential), and the general economic situation, they are better off or worse off than a year earlier, or the same. The positive responses are netted out against the negative responses, and an index is constructed out of all these responses. Since March 2019, i.e. a year before the Covid lockdown, the index has been continuously negative. The majority surveyed have considered themselves worse off each successive year for the past four years uninterruptedly – i.e., they consider themselves to be in continuous decline. In the latest round of the survey (July 2023), 30 per cent considered the economic situation to be better than a year earlier; 19 per cent considered it to be the same; and 51 per cent considered it to be worse.[20]

As a result of lack of demand, industrial production has stagnated or fallen. In 16 out of 23 manufacturing industries in the Index of Industrial Production (IIP), with a weight of 56 per cent in the index, output was lower in 2022-23 than four years earlier. These included relatively labour-intensive consumer goods industries such as beverages, textiles, apparel, leather products, wood products, paper products, and rubber and plastic products; as well as durable consumer goods such as electrical equipment and motor vehicles.[21] The production of ‘consumer durables’ in 2022-23 was 12 per cent lower than for 2018-19.[22]

All these data show beyond doubt that the incomes and consumption of the mass of working people in the country have shrunk outright, and their condition is steadily deteriorating.

While the rulers may distribute a few well-publicised welfare payments or reductions in prices from time to time, they do so by cutting overall expenditure, and thereby reducing aggregate demand in the economy, reducing the purchasing power of the people and thereby starving the small units and informal sector which depend on that purchasing power. All this to impress foreign investors and thereby bring about what the Finance Minister considers to be increased “flow of capital in our financial system”.

3. The Indian ruling classes’ own calculations

(an excerpt from an earlier note)

By way of conclusion, we reproduce below a long excerpt from our earlier note of 2021. (Note: The figures are somewhat dated.)

Given that there are no benefits, only costs, for India from such investment, why are the Indian rulers striving for this?

Firstly, as is well known, India’s economy and political life have come under an unprecedented level of private corporate control; and the summit of India’s private corporate sector is now more closely integrated with international capital than ever. This takes the form of foreign loans, foreign portfolio investment and foreign direct investment. Surajit Mazumdar notes:

The spectacular expansion of Indian big business during the last two decades has heavily depended on, rather than being despite, international integration. Foreign capital flows and access to external capital markets has played an important role in enabling both domestic and overseas expansion of Indian capital. One expression of that has been the increased recourse to foreign financing by Indian firms. Capital inflows have also contributed indirectly; given India’s current account situation, they were essential requirements for the easing of norms for Indian investment abroad, and they have been important movers of the Indian stock market creating conditions whereby Indian firms could raise cheap capital. Access to technology and imports of capital goods and intermediate products where they are cheaper has contributed to the competitiveness of Indian firms and enabled them to find some niches in which they could grow, often in a collaborative arrangement with foreign capital.

By June 2021, India’s non-Government external debt – essentially the foreign borrowings of the private corporate sector – amounted to $464 billion, or 81 per cent of India’s external debt, and 16.4 per cent of India’s GDP. The large flows of foreign capital into India, and the surging foreign exchange reserves, also make the Indian corporate sector less ‘risky’ in the eyes of foreign lenders, and allow the corporate sector to borrow more cheaply abroad. Indeed, their foreign loans have to an extent reduced their dependence on credit from Indian banks.

It is noteworthy that the large foreign exchange reserves have reassured the Government that they can relax restrictions on large outward foreign direct investment (OFDI) by Indian firms, which is a step toward capital account convertibility; at present automatic approval is given for outward investments up to 400 per cent of the investing firm’s net worth. Cumulative OFDI during 2000-01 to 2018-19 came to $179.5 billion.[23] A substantial portion of this may be ‘round-tripped’ capital, i.e., Indian firms sending out capital as outward FDI, and bringing it back in under another name (benami) as inward FDI. As one study points out,

It is clear that Indian OFDI flows are dominated by economies considered to have an advantageous fiscal regime such as Mauritius, Singapore, the British Virgin Islands, the Netherlands, Switzerland and Cyprus. In addition to possessing favourable treaties covering bilateral investment, double-taxation avoidance or comprehensive economic partnerships with India, many of these countries also offer low tax rates and access to international financial markets in order to attract Indian firms. As such economies are less likely to be the ultimate destination of Indian OFDI flows, one part of such flows may be redirected to other countries while another part could be round-tripping, i.e. coming back to India as FDI inflows.[24]

The returns on such outward FDI are likely to be lower than the returns on the inward FDI (the foreign firms to which such investment goes are shell firms, whereas the Indian firms receiving such investment are real firms). Hence such ‘round-tripping’ flows also act as a continuing drain.

Apart from such round-tripped capital, the top Indian firms are major recipients of foreign investment and loans. Mukesh Ambani has sold 33 per cent of Reliance Jio to US firms, and has given them places on the board; and foreign portfolio investors hold more than 25 per cent of the parent firm Reliance Industries.[25] Foreign inflows have helped propel Ambani to the position of the richest man in Asia and 10th richest in the world. The Tata group’s giant foreign acquisitions were funded in large measure by foreign borrowings. The Adani group is among the most indebted corporate groups in India, with outstanding loans of $30 billion, but is still able to tap foreign markets for capital without difficulty. It has sold large stakes in its firms to foreign giants such as Total, and “international groups are queueing up to partner with the mogul.”[26]

The extent of integration is exemplified by the first-generation Indian tycoon Anil Agarwal, a metal scrap dealer-turned-industrialist who profited greatly off India’s early privatisations. In order to get access to international capital markets in the 2000s, Agarwal incorporated the firm Vedanta Resources in London. Eventually the group became a multinational conglomerate headquartered in London, where Agarwal himself resides.[27]

Given the above, India’s corporate tycoons welcome measures for further integration of the Indian economy with international capital, such as opening the government bond market and moving towards capital account convertibility. They look forward to a situation in which they are completely free (they already are partly able) to move their capital in and out of the country, much in the way they themselves do.

But even as Ambani, Tata, Adani and Agarwal have all attempted to ‘internationalise’ their groups and have purchased assets abroad, their stakes remain overwhelmingly in India. Their efforts to expand internationally have so far seen at best minor successes, and also some spectacular failures. (Interestingly, Tata’s largest foreign acquisition has proved a disaster; the group has survived and been able to service foreign loans taken for the acquisition of Corus on the strength of its domestic operations. And while Vedanta is headquartered in London, most of its assets are in India.)

It is not Indian big business houses’ technological dynamism or industrial entrepreneurship that secure their dominant position in India. Rather it is their India-specific capabilities – viz., their ability to ‘manage’ the Indian State regulatory machinery and political forces, their ability to capture Indian markets through anti-competitive methods, and the influence they wield in Indian society. Those ‘native’ mercantile skills in turn ensure their access to foreign capital for their expansion. Correspondingly, foreign financial capital turns to these ‘Indian’ firms for access to India. As such, the relationship of India’s top corporate firms to the Indian economy is subsumed in the relationship of imperialism with India.

Thus the interests of the top corporate houses have in a crucial sense seceded from India itself, even as their stakes predominantly lie here….

At the same time, the vast majority of the Indian people have neither such ties, nor free mobility options open to them, as the elite. For them, the further integration of India with the global economy portends a grim future, marked by a depression of demand and instability. When the economy is drained, it is the surplus created by their labour that gets drained. When the economy is destabilised by foreign capital flows, it is their livelihoods that get destroyed. When the economy is ‘restructured’, it is their labour that gets devalued. It is they who will have to wage a struggle for real independence, a travesty of which is being celebrated this year with pomp and wind.

Notes

[1] India would be added starting in June 2024, with a 1 per cent weight in the index, proceeding in steps till March 2025, by when it would reach a 10 per cent weightage in the index.

[2] NSDL FPI Monitor, September 29, 2023.

[3] Financial firms project the reduction at 10-15 basis points, i.e., 0.10 to 0.15 percentage points, in the near future.

[4] “Govt bonds’ JP Morgan index inclusion to boost rupee, help finance CAD: CEA”, Business Standard, September 22, 2023.

[5] For example, see the comments of the economists of HDFC Bank, Bank of Baroda and others cited in Reuters, “India’s inclusion in EM bond index can spark higher FX volatility: Bankers”, September 22, 2023.

[6] Bilge Erten, Anton Korinek, and José Antonio Ocampo, “Capital controls: Theory and evidence”, Working Paper, National Bureau of Economic Research, 2019; Anton Korinek, Prakash Loungani, and Jonathan D. Ostry, “The IMF’s updated view on capital controls: Welcome fixes but major rethinking is still needed”, April 18, 2022,https://www.brookings.edu/articles/the-imfs-updated-view-on-capital-controls-welcome-fixes-but-major-rethinking-is-still-needed/

[7] Rakesh Mohan and Amshika Amar, “Holes in the financial safety net”, Indian Express, August 22. 2023.

[8] “Govt bonds’ JP Morgan index inclusion to boost rupee, help finance CAD: CEA”.

[9] Ibid.

[10] This includes all types of foreign liabilities and foreign assets. RBI, “India’s International Investment Position, March 2023”, June 2023.

[11] RBI Annual Report 2022-23, Table XII.8, p. 276.

[12] Economic Survey 2020-21, Chapter 3, titled “Does India’s Sovereign Credit Rating Reflect Its Fundamentals? No!”

[13] “Govt bonds’ JP Morgan index inclusion to boost rupee, help finance CAD: CEA”.

[14] Interview with Bloomberg Quint, September 26, 2023 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KTYMooXrS7Y

[15] Shrimi Choudhary, “Bond inclusion shows our fiscal prudence: Fin secy”, Business Standard, September 23, 2023.

[16] The Central Government’s policies have squeezed state government spending, too, and so GDP data show that Government final consumption expenditure (GFCE) did not grow at all in 2022-23 in real terms. In the first quarter of 2023-24, GFCE has fallen year-on-year.

[17] Budget 2023-24 documents. See also Asmi Sharma and Nancy Pathak, “Narendra Modi’s Decade in Power Has Brought a Shrinking Welfare Landscape to India”, The Wire, September 27, 2023. https://thewire.in/economy/narendra-modis-decade-in-power-has-brought-a-shrinking-welfare-landscape-to-india This shows how Budgetary allocations for these heads have fallen since 2014.

[18] Jean Dreze, “Since 2014, the poorest communities are earning less”, Indian Express, May 25, 2023, https://indianexpress.com/article/opinion/columns/since-2014-the-poorest-communities-are-earning-less-8625367/; Himanshu, “Worker incomes in India are still signalling tough circumstances”, Mint, March 23, 2023, https://www.livemint.com/opinion/columns/worker-incomes-in-india-are-still-signalling-tough-circumstances-11679592796284.html

[19] National Council for Applied Economic Research (NCAER), Socio-economic impact assessment of food delivery platform workers, August 2023.

[20] https://www.rbi.org.in/Scripts/BimonthlyPublications.aspx?head=Consumer%20Confidence%20Survey%20-%20Bi-monthly

[21] Output in 5 industries, with a weight of 39 per cent saw growth between 2018-19 and 2022-23. These were capital-intensive heavy industries such as basic metals, non-metallic mineral products, pharmaceuticals and petroleum & coke. In the case of 2 industries, with a weight of 5 per cent, output remained at virtually the same level.

[22] Index of Industrial Production data.

[23] Reji K. Joseph, “Outward FDI from India: Review of Policy and Emerging Trends”, Institute for Studies in Industrial Development, Working Paper 214, November 2019.

[24] Jaya Prakash Pradhan, “Indian outward FDI: A review of recent developments”, Transnational Corporations, vol. 24, no. 2, June 2017 https://unctad.org/webflyer/transnational-corporations-vol-24-no-2

[25] See RUPE, Crisis and Predation, pp. 167-73.

[26] Stephanie Findlay and Hudson Lockett, “‘Modi’s Rockefeller’: Gautam Adani and the concentration of power in India”, Financial Times, November 13, 2020.

[27] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Anil_Agarwal_(industrialist)

(Research Unit for Political Economy is a trust based in Mumbai that brings out material seeking to explain day-to-day issues of Indian economic life in simple terms and link them with the nature of the country’s political economy.)