History of Luv-Kush

The word kushalava in Sanskrit literature like Manusmriti and Arthashastra refer to lowborn travelling entertainers. This feels strange as Kusha and Lava are the names of Ram’s twin sons — Ram who is the greatest king of Indian lore. In Sikh folklore, endorsed by the 18th century Bachitar Natak, the Bedi and Sodhi clans to which Guru Nanak (1st guru) and Guru Govind (10th and last human guru) belong, claim descent from Luv and Kush.

Thus we find Ram’s descendants linked to powerful royalty as well as to powerless nomadic communities of dancers, singers and storytellers. Spiritually this sounds sublime. Materially, one cannot help but wonder how two groups of people — at two ends of the political and economic hierarchy — trace descent to Luv and Kush. The answer may lie in the history of the story of Luv and Kush.

Vedic roots of early versions

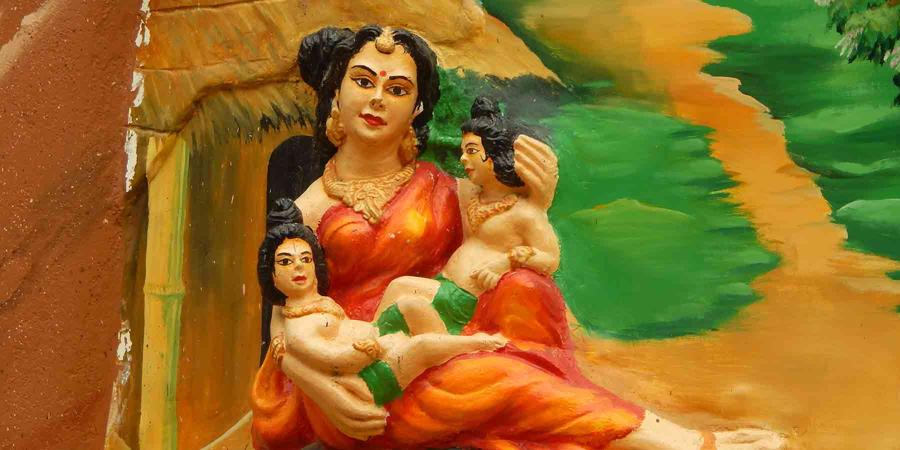

The final chapter of Valmiki Ramayana, known as Uttara Kanda, informs us about how the Ramayana was first narrated in front of Ram himself by his sons, the twins Luv and Kush. The father doesn’t recognise his children; the children do not recognise their father.

The children were born in the forest and raised by their mother in the hermitage of the poet sage Valmiki, who teaches them his Ramayana, and gets them to present this to the king. The location of Valmiki’s Ramayana is in dispute — some say it is on the Indo-Nepal border while others trace it to Avani Bettar in Karnataka.

In the earliest versions of the Valmiki Ramayana, dated between 200 BCE and 200 CE, the king hears the two boys sing with vina in their hand during the ritual and finally remembers his wife, recognises the children, after which his wife Sita decides to disappear under the earth. In Kalidasa Raghuvamsa, dated to 500 CE, the boys sing on the streets of the city. There is no vina in their hand. And there is no emphasis on the ritual arena.

This episode of storytelling during Ashwamedha yagna has Vedic roots. As per the Taitriya Brahamana, dated to 700 BCE, and later Shrauta Sutra, during the Ashwamedha Yagya one of the rituals involved a Brahmin and a Kshatriya praising the king through the ceremony, playing the stringed instrument known as the vina. The Brahmin would speak of the generosity of the king, while the Kshatriya would speak of the bravery of the king in battle. Luv and Kush are clearly performing this role during Ram’s Ashwamedha yagya as per Valmiki’s narrative but not as per Kalidasa’s narrative.

Luv and Kush are sometimes described as being both Kshatriya and Brahmin. This is explained as follows: As per some Ramayana retellings such as the one in the 10th century Katha-sarit-sagar, Sita gave birth to only one son, Luv. She gave the child in care of Valmiki and went to perform her ablutions to the river. While she was away, Valmiki lost the baby and, in a panic, created a duplicate using Kusha grass. Luv, born of Sita, is thus Kshatriya while Kush, born of grass, is Brahmin.

Warriors of later versions

In later versions of the story, the sons of Ram are shown as warriors who capture the royal horse and challenge their own father in battle. The earliest references to Luv and Kush capturing Ram’s royal horse, which brings them in conflict with Ram’s army, comes from the Jain narratives such as the Paumachariya of Vimalasuri, composed in the Prakrit language, dated to 3rd century CE, where Ram is called Padma and the boys are referred to as Lavana and Ankusha. This is later found in the 5th century Padma Purana and the 8th century Sanskrit play Uttararamacharita by Bhavbhuti.

In a much later narrative in the 12th century, the Jaiminiya Ashwamedha, there is a reference that Ram did not even pay attention to the songs that Luv and Kush was singing and this upset the boys who then noticed the golden statue of Sita beside Ram and realised that the king who they were praising had abandoned his wife described as the faithful one in the Valmiki Ramayana. This is what turns the boys against Ram and turns them into warriors.

In different versions we find the situation escalating: Luv and Kush defeat the army in some versions, while in others they defeat Hanuman and Sugriva and the Vanaras. And there are still versions where the defeat Lakshmana and Ram’s other brothers. Finally there are versions where even Ram is defeated. Thus they establish the supremacy of Sita’s power and the fact that dharma is on Sita’s side and not on Ayodhya’s side.

The direct confrontation between father and sons is clearly a later retelling, perhaps inspired by the Mahabharat story, where Arjun is confronted by his own son Babruvahan during the Ashwamedha performed by Yudhishthira.

An even later retelling the Assamese Ramayan, Adbhuta Ramayana, tells us how Sita when she descends to the earth, misses her children. So she gets Vasuki, the king of snakes, to abduct Luv and Kush from Ram’s kingdom and bring them to the nether world, which brings the naglok in confrontation with Hanuman. After much fighting, the family is reunited.

Thus we see how stories change over time. Luv and Kush go on to establish kingdoms in India. And there are many royal dynasties and cities and communities that trace their origins to the sons of Ram.

(Devdutt Pattanaik writes on relevance of mythology in modern times, especially in areas of management, governance and leadership. He defines mythology as cultural truths revealed through stories, symbols and rituals. Courtesy: Devdutt Pattanaik’s blog.)

In the popular understanding of Ramayana, Sita gave birth to twins Luv and Kush who challenged their father and defeated him in battle and restored the dignity of Sita. However, in the many retellings of Ramayana found across the world, we learn Sita delivered only one child called Luv. She raised this child in the ashram of Valmiki. One day, when she went to gather fruits and berries from the forest, she left the child in the care of Valmiki. But when she returned, she found not one but two children. Valmiki explained that while she was away Luv had wandered off, and he could not find the child. In panic, he used his magical powers to create a new child. He gathered Kusha grass, fashioned out of it, a doll, breathed life into it and created a second child which was the very likeness of the first child. This is how the second twin was born.

This story is found across India in many folk retellings and makes one wonder why is it that storytellers felt the need to show that Sita’s twins were not born naturally but as a result of magic? Is it that twin children were considered auspicious and therefore you need an alternate explanation for the existence of two sons? Of course, we can only speculate on this.

In Sri Lanka, Sita does not have two sons but three sons. The story goes that Valmiki did produce the second child using Kusha grass and his magical powers, but Sita does not believe that he’s capable of doing so. To prove he takes a flower and fashions a child out of flowers and creates a third child. And thus, these three children defeat Ram in battle and become famous as a trio of gods, who are invoked and play a very important role in Sri Lankan folk rituals and traditions. Their dance is performed in Vishnu temples, Vishnu being a guardian of the Buddha in Sri Lankan lore. These three sons of Ram are also called the sons of Vishnu and invoked to protect kings and defend the land from ghosts and goblins.

In Sri Lankan lore, when Prince Vijay came from India, along with 600 people and colonised the land he fell in love in Sri Lanka with a Yakshini, a local forest spirit, one can say a tribal woman. However, he felt that he would not be recognized as kings by the kings of India unless he married into a royal family. And so, he abandoned the Yakshini and married the princess of Madurai, as a result of which he and his son suffered from various skin ailments. Vijay and son invoked the three sons of a Sita who cured them of illness. And since then, three sons of Sita are often ritually invoked in temple rituals to get rid of curses.

In Sri Lankan Ramayana there are many variations in the story. For example, Ram’s exile happens not because of any palace politics, but because of astrological reasons, the malevolent effect of the planet Saturn, which is why he goes into the forest in the form of an elephant for seven years, during which Sita is abducted. Ram, with the help of Hanuman and Lakshman, rescues her. But one day Ram finds that Sita has painted an image of Ravana on a banana leaf which is why he sends out of the palace into the forest, where he bears three sons who become the guardian spirits of Lanka.

(Devdutt Pattanaik writes on relevance of mythology in modern times, especially in areas of management, governance and leadership. He defines mythology as cultural truths revealed through stories, symbols and rituals. Courtesy: Devdutt Pattanaik’s blog.)