C.P. Geevan

By about 3:30 pm (IST) on April 14, the total number of confirmed COVID-19 cases neared 2 million around the world, and deaths were about to exceed the 120,500 mark. But as if by a miracle, the number of confirmed cases in India was just about 10,540, per official figures. Scepticism about this unexpectedly low figure is often met with the refrain that it is thanks to containment efforts, although the virus’s spread could have started in January itself.

The drastic limiting of social contacts and the nationwide lockdown may have played their intended purpose – but they couldn’t have been adequate. Physical distancing norms and the nationwide lockdown from March 25 were imposed unevenly across states, and the massive social and economic disruption that followed couldn’t have helped.

This said, there are no known reasons for why the disease’s rate of spread appears to be lower in India. Even so, it is difficult not to be sceptical of the official data. If we assume that the disease is nearly as infectious as it seems to be in other geographies, why are the reported numbers so low? Is the actual incidence not being captured in the data? Are there bottlenecks in the data-flow? Are there flaws in the effort to assess the disease’s prevalence? Or are there other factors at work that obscure India’s efforts to accurately determine the disease spread?

No airport-screening system can detect all infected persons. Until March 25, 2020, almost all of India’s confirmed cases were related to air travel. A comparison of the airport traffic data and the cases detected at airports points to large anomalies in the airport-screening programme and which can’t be explained by minor variations.

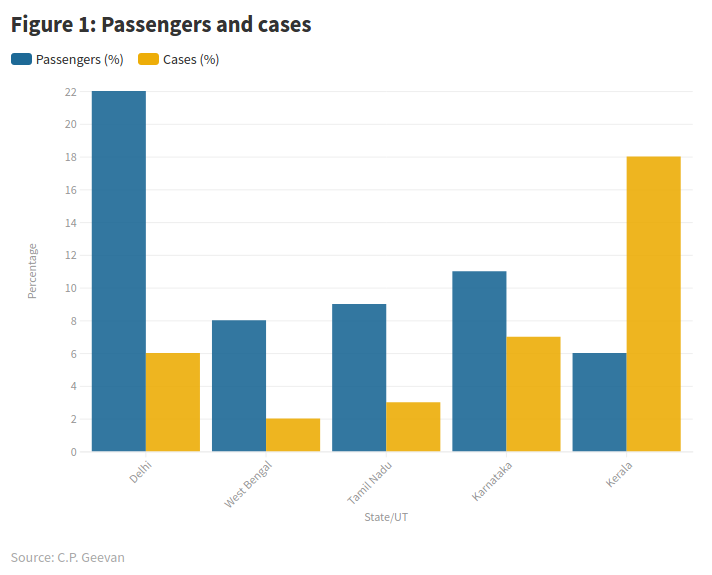

On March 24, before the nationwide lockdown, India had 519 confirmed cases. Of this, if we take the relative share of state-wise confirmed cases and compare them to air-passenger traffic through all airports in each state (data of FY 2017-18), the discrepancies in airport-screening strategy will become clear (see figure 1).

Delhi had 6% of the confirmed cases and accounted for 22% of passengers. West Bengal, Tamil Nadu and Karnataka together accounted for 12% of confirmed cases and accounted for about 28% of passengers. In contrast, Kerala accounted for 18% of confirmed cases but only 6% of passenger traffic. This lack of pattern shows up the big differences in the effectiveness of airport-based screening and contact-tracing. It also underscores the possibility that there are several times the number of undetected cases as there are already detected cases, contributing to the disease’s spread.

A scientific paper published on February 24 shows that even in the best-case scenarios, airport-screening is likely to have missed over half of all infected passengers. In fact, most cases in the US were not detectable when they passed through airport-screening, and more cases were detected several days later, when many who had passed through screening needed medical assistance.

But inexplicably, in India, only a few of those not detected in airport-screenings have sought medical help. Therefore, India has a strange situation. Where are these people?

Disease spread: absent or hidden?

The disruption of normal life and closure of many healthcare facilities have made it difficult for people to receive medical attention. A Brookings Institute study of India’s healthcare system in 2004-2014 found that at the end of that decade, fully 75% of outpatient care and 55% of inpatient care was fulfilled by the private sector. Similarly, the disruption caused by the lockdown has contracted healthcare facilities available, especially in the private sector, and disrupted access to doctors and hospitals.

There have been news reports from different parts of India about people walking or cycling with patients to reach far-flung public health facilities. While a few elective surgeries and treatments can be postponed, in India many are in line awaiting their turn to receive urgent treatment and surgeries. In addition, there is an evident tendency among many to avoid the healthcare system for fear of being tested for COVID-19. People seem more afraid of the social consequences of testing positive and the quarantine than of the virus itself. These attitudes in turn contribute to rendering the disease, and information about it, invisible.

There is an assumption that if there are as many deaths in India as there are in, say, China, Europe, the US or the UK, then it would be easily noticed. But this isn’t necessarily so! First, the lockdown has most likely increased the mortality above the normal, or at least the number of deaths per day even without COVID-19. Second, according to a report on the Medical Certification of the Cause of Death in 2017 (published by the Registrar General of India in 2019), the cause is medically certified for only 22% of registered deaths.

The annual mortality rate for India is nearly 7.3 per thousand. The corresponding deaths per district works out to be about 37 per day. A thousand additional deaths in a day at the country-level in a day translates to less than two additional deaths per district. This is likely to go unnoticed. Only when there are many deaths in a cluster will the uptick become noticeable. Therefore, until normal life is restored and all fears are dispelled, the virus’s presence in India is likely to be hidden for the most part even as it spreads.

It’s possible there are other, more problematic reasons that explain the peculiarities of India’s data. However, there’s no information or data available in the public domain to indicate India is making its best efforts to assess the disease’s spread. As Priyanka Pulla wrote in The Wire Science on March 20, the central agencies responsible for the technical aspects of the country’s COVID-19 response – Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR) and the National Centre for Disease Control – have been very opaque, staying tight-lipped about their surveillance mechanism.

Estimating realistic numbers

Officials of the Union health ministry have consistently adopted a conservative and tepid approach to monitoring and COVID-19 disease surveillance. The number of India’s tests per million people is 149, compared to the US’s 8,894, Canada’s 11,591 and Germany’s nearly 15,730. There was considerable delay in expanding the scope of testing as well. And when the ICMR did expand it, it did so reluctantly, without a smart plan to rapidly assess the virus’s spread in different parts of India. Additionally, there seems to be no emphasis on developing a ‘heat map’ of the disease’s presence across the country to quickly identify emerging hotspots in coordination with state authorities.

The health ministry updated the scope of testing through notifications on March 9, 16 and 20. Before that, the government had issued travel advisories mandating quarantine for international passengers from notified countries. It is evident that health authorities haven’t displayed any urgency in comprehensively assessing the spread or in expanding testing despite the WHO’s emphasis on conducting more tests.

Rather than wait for more testing kits, a better approach is to streamline disease surveillance, tweaking it to enable rapid reporting through innovative use of technology. District-level health authorities ought to be taking urgent steps to identify clusters where there are unusual patterns of respiratory illnesses. There is no dearth of expertise to develop necessary technology solutions. Sadly, government agencies seem to lack both the will and the interest.

The ministry has also repeatedly asserted that it hasn’t found any evidence of community transmission. But it’s doubtful if the ministry’s approach could unearth the evidence. An approach that is not open to scrutiny will automatically lack credibility. Surely absence of evidence can’t be taken to be evidence of absence. The ICMR’s latest update about testing is proof enough, both from scientific and public health perspectives. This cryptic document – whose metadata suggests it was ready by about 10:30 pm on April 14 – states:

“A total of 2,44,893 samples from 2,29,426 individuals have been tested as on 14 April 2020, 9 PM IST. 10,307 individuals have been confirmed positive among suspected cases and contacts of known positive cases in India. Today, on 14 April 2020, till 9 PM IST, 26,351 samples have been reported. Of these, 853 were positive for SARS-CoV-2.”

It’s not clear from this update as to what the scope of sampling efforts is, what they represent, how and when the individuals who were tested were originally selected, what tests were used, and so forth. Anyway, the document indicates that nearly 4.5% of the individuals tested were positive for COVID-19; put differently, at least 4.5% of those tested were disease carriers and that the actual number is likely to be higher because the tests can’t detect all those infected (i.e. false negatives). Since we know little about the samples, the figure isn’t necessarily a good estimate of the disease’s spread. The cumulative number of confirmed cases – about 4,270 on April 6 – reached 10,752 by April 14, i.e., doubling every six days or so.

The renowned virologist Dr T. Jacob John, formerly with the Christian Medical College, Vellore, had warned of an imminent avalanche of cases due to high infectivity.

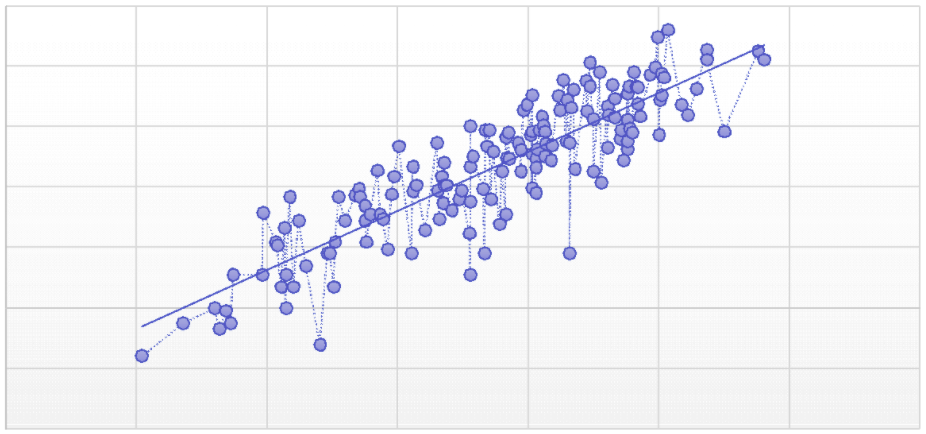

One way to estimate the numbers for India is to use the global data adjusted for population size and attempt a best fit for Tests per Million (TpM) and the Total Confirmed Cases (TC) per Million (TCpM). The regression equation can be used to estimate total confirmed cases for India. Using the logarithm of these values provides a good fit (figure 2).

Figure 2: Plot of logarithmic values and linear regression.

[Data: Worldometers (accessed April 11, 2020)]

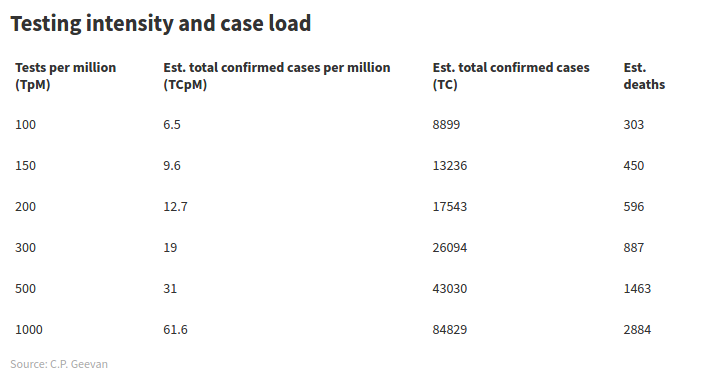

The total number of confirmed cases estimated using the regression and corresponding deaths based on current COVID-19 fatality rate in India (3.4%) is shown in the table below. Currently, India’s testing intensity is 149 TpM, with 10,541 confirmed cases. For a testing intensity of 150 TpM, the estimate of confirmed cases comes to 13,236.

***

India’s data gathering and dysfunctional systems under lockdown seem to be shaping its large deviation from the global pattern in the general COVID-19 epidemiological trend. Not only is India facing severe constraints in scaling up testing, there is no news of any effort to find smarter solutions to reliably assess the disease’s spread.

In the absence of credible epidemiological studies, the apparently slow spread of COVID-19 in India seems to be rooted in limitations of measurement and not any significant differences in epidemiological characteristics.

A regression model based on global data for testing and confirmed cases illustrates the large anomaly in India’s confirmed cases vis-à-vis the global data. Given India’s population size and the limited medical certification of deaths, COVID-19 mortality would be hardly noticeable unless there are clusters with a large number of infected individuals.

[C.P. Geevan is a visiting fellow at the Centre for Socio-economic and Environmental Studies (CSES), Kochi.]