A. Raghu Kumar

In the midst of voluminous literature and in the confused and contradictory ways Gandhi has been understood or misunderstood, one may even say – as Dr. Omkar Sane[1] said: ‘Honestly, none of us have never really tried to understand Gandhi, at least not beyond our convenience…. … the charm of Gandhi lies in him being misunderstood. It works for Gandhi to remain misunderstood. That makes him greater. That makes the idea of ‘Gandhi’ much grander. … Just the fact that for generations together, nobody can really understand him puts him on a pedestal, a higher ground, where mortals may not tread. …’ There are also many like Shashi Deshpande who consider that no more literature is required to understand Gandhi than his own autobiography, My Experiments with Truth (or his writings now available in almost hundred volumes).[2]

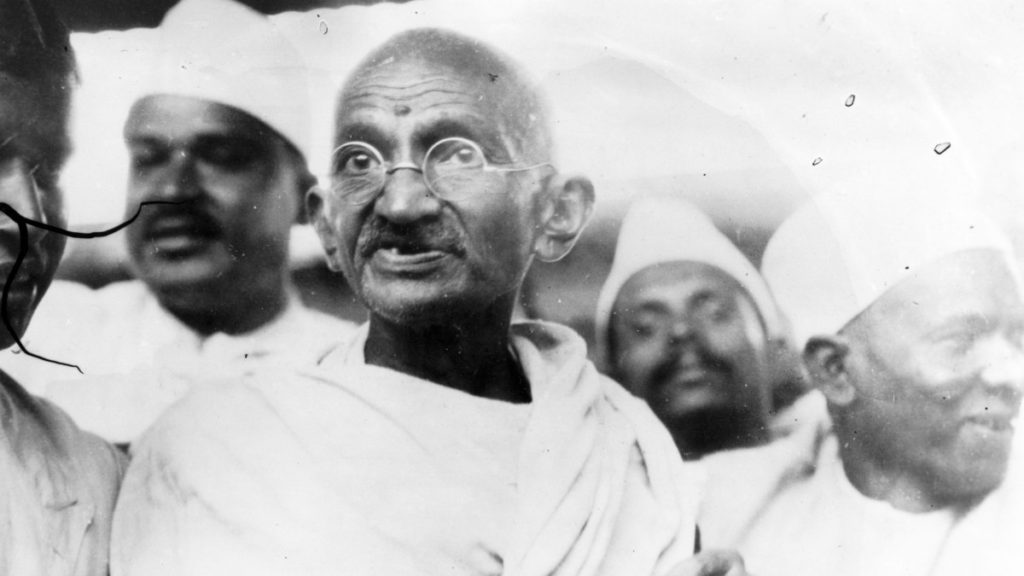

On 15 August 1947, when the crowds were swarming into New Delhi from all sides, and Nehru was about to deliver ‘the tryst with destiny’, “(t)he first uncertain sputtering of a candle had appeared in the windows of the house on Beliaghata Road just after 2 am, an hour ahead of Gandhi’s usual rising time. The glorious day when his people would savor at last their freedom should have been an apotheosis for Gandhi, the culmination of a life of struggle, the final triumph of a movement which had stirred the admiration of the world. It was anything but that. There was no joy in the heart of the man in Hydari House. The victory for which Gandhi had sacrificed so much had the taste of ashes, and his triumph was indelibly tainted by the prospects of a coming tragedy.… ‘I am groping,’ he had written to a friend the evening before. ‘Have I led the country astray?’”[3] How do we understand this person who refuses to rejoice in his own offspring ‘freedom’?

Gandhi emerged as a challenge or a reply to the dominant development theories of the West or to the progress of the civilization of the West, more particularly the path it had taken from the industrial civilization onwards. To understand Gandhi we need to know about the West’s philosophical journey from the 16th and 17th centuries onwards, from the days when religion and the State got separated, and from the times violence as had assumed the status of an inevitable tool or TINA factor in the social change. He was thus propounding an antithesis of the thesis of the West in two ways, i.e., he was articulating his arguments against the distancing of religion from politics (religion in his diction being morality and spirituality) and against the unavoidable nature of violence. The significance of many of his preliminary conclusions was that they were mostly derived from his reading of certain subaltern movements within the West such as vegetarians, Quakers, Fabians and softer versions of the anarchists etc. Most of the intellectuals, almost from all hues, at that time were more enamored with the West’s project of modernity, positive sciences, industrialization, and Parliamentary democracy etc. In this milieu, Gandhi stood alone during his lifetime. Though he derived much strength for his ideas mostly from the traditional Hindu sources, he drew them equally from his extensive reading of the West’s convulsions.

From the first biographical sketch of Gandhi written by Doke[4], a Christian missionary, in South Africa in 1909, there are several attempts to understand Gandhi. There are hundreds of biographical and philosophical inquiries. For this present discussion, I have chosen six viewpoints in approaching him, which I call as shatdarsanas[5]. For approaching Gandhi, the systems I found useful are: 1. the subaltern Western traditions in Christianity such as Quakers, Fabians, pacifists, and etc.; 2. dissident Communist / Marxist traditions; 3. psychological studies – individual and social; 4. counter-cultural studies; 5. subaltern traditions within the sanatana Hindu dharma; and 6. Anarchist traditions. For the above reason I restrict my presentation to the understanding of Gandhi from the sources of Romain Rolland, Pannalal Dasgupta, Erik H. Erikson, Ashis Nandy, Anthony J. Parel and my own studies into the anarchic traditions. However, there can many more methods in approaching this enigmatic soul.

1. Romain Rolland’s Gandhi

Romain Rolland (1866-1944), the French dramatist, art historian and mystic, and a nobel laureate of 1915 for literature, defined himself as one belonging to the ‘antique species.’ He was a different pacifist. He was also strongly influenced by the Vedanta philosophy of India, primarily through the works of Swami Vivekananda. Without ever having visited India, he wrote three important books, one each on Ramakrishna Paramahamsa, Vivekananda and Gandhi. He was also instrumental in diverting the platonic love of Madeleine Slade (Meerabehn), the daughter of a British admiral, towards Beethoven to Gandhi. Long before the world bestowed attention on Gandhi, Rolland probed into the phenomenon called ‘Gandhi’ and made known to humanity the spiritual greatness of this man. Gandhi was known in South Africa and England for his contribution to the cause of Indians in South Africa between 1893 and 1914. But Rolland introduced Gandhi to the other parts of Europe. His work in French, Mahatma Gandhi – The Man who became One with the Universal Being, made one of the first systematic analyses of Gandhi’s philosophy and work, including nonviolence.

Rolland[6] found in Gandhi ‘infinite patience and infinite love’, and quotes W.W. Pearson, who met Gandhi in South Africa, and who instinctively thought of St. Francis of Assisi. In Rolland’s consideration, Gandhi was one ‘who has introduced into human politics the strongest religious impetus of the last two thousand years.’ In other words, Gandhi is religious by nature, and his doctrine is essentially religious. ‘He is a political leader by necessity, because other leaders disappear, and the force of circumstances obliges him to pilot the ship through storm and give practical political expression to his doctrine.’[7]

Rolland[8] being a pacifist examined the nature of Gandhi’s nonviolence and expresses that: ‘Nothing is more false than to call Gandhi’s campaign a movement of passive resistance. No one has a greater horror of passivity than this tireless fighter, who is one of the most heroic incarnations of a man who resists. The soul of his movement is active resistance – resistance which finds outlet, not in violence, but in the active force of love, faith, and sacrifice. This threefold energy is expressed in the word Satyagraha.’ ‘It was ‘a method in startling opposition to that of our European revolutionaries.’

‘Gandhi is an exception among prophets and mystics, for he sees no visions, has no revelations; he does not try to persuade himself that he is guided supernaturally, nor does he try to make others believe it. Radiant sincerity is his. His forehead remains calm and clear, his heart devoid of vanity. He is a man, like all other men. He is not a saint. He will not have the people call him one.’[9] But Rolland held out a hope: ‘One thing is certain: either Gandhi’s spirit will triumph, or it will manifest itself again, as were manifested, centuries before the Messiah and Buddha, till there finally is manifested. … the perfect incarnation of the principle of life which will lead a new humanity on to a new path.’[10]

2. Pannalal Dasgupta’s Gandhi

The very idea that Gandhi was a revolutionary in terms of Marxist description appears, at the outset, to be unthinkable. A preacher and practitioner of non-violence, an eternal seeker of Truth as God, an apostle of peace and an enigmatic opponent of modern civilization of the West model, can he be understood as a revolutionary, on par with and in the great lineage of Marx and Lenin? Any Marxist trained mind would abhor the very thought and may also pooh-pooh such propositions as foolish and absurd. In my search for a different analysis of Mahatma Gandhi, more specifically from a Marxist point of view, I found reading of Revolutionary Gandhi by Pannalal Dasgupta[11], a revolutionary Marxist of yesteryears and leader of the Revolutionary Communist Party as very fruitful.

“Indian Communists have never tried properly to understand Gandhiji”, says Pannalal[12]. “So, I have tried to acquaint people with the two most important phenomena and ideologies of our times, Gandhism and Leninism. I have explained Gandhism in the light of Marxism and also analyzed Marxian thought and action in the Gandhian light”, declares the author. Two major objectives of the book are indicated at the end, in the Epilogue[13]: “My purpose has been to show Gandhi in a new light to the Indian leftists and to present the historical Gandhi to the so-called diehard Gandhians”.

“I look upon Gandhi, Marx, Lenin and other men of the age as forming a powerful giant telescope and introscope, if I may use that word to mean an instrument which shows what goes on with in my mind.” In fact, the work is also a critique of three other works of that time, which the author considers just and necessary to offer, and those three works were Pyarelal’s Mahatama: Last Phase, Prof. Hiren Mukherjee’s Gandhiji and E.M.S. Namboodripad’s Mahatma and the Ism. It also offers a critique of the views of Maulana Azad and C.R. Das and also compares the views of Gandhi and Ravindranath Tagore, and Gandhi and Subhas Chandra Bose.

“The call of the Gita took Sri Aurobindo away from politics and sent him into total seclusion, and the same Gita inspired revolutionaries in India to wage armed struggle. And it is the Gita that Gandhiji called the non-violent yoga of action and adopted it as his path towards the realization of God…..”[14] Concluding the examination of Gandhi’s perplexing ideas on non-violence, the author contends that “in brief, the application of non-violence and satyagraha in each case had not been easy and smooth, and in his (Gandhiji’s) experiments with and exploration of this path, Gandhiji had to keep probing and questioning himself until his final days. He kept asking himself time and again at Naokhali whether at all the non-violence of the brave was possible. His quest was incomplete, for on the last lap of his life’s journey, he could not make the country strong through the non-violence of the brave…”[15]

After discussing various stands on the issue of Dalits, Pannalal considers that in fact it is Gandhi who elevated caste problem into class-struggle. By looking at the problem as not of caste, but of high and low, the exploiter and the exploited, he contends that Gandhi projected the problem more as a problem relating to the class struggle. Pannalal contends that “Gandhiji also put into practice the fundamental ideals of communism and socialism in a way that the communists or socialists of his time could only envy”. “In his outlook as well as his personal life, Gandhiji attained the level of the truly classless human being. “Gandhiji may not have been a communist, but he could certainly have been a worthy member of a classless society.”[16]

In the Epilogue, he says[17]: “The sum and substance of my discussion in the foregoing paragraphs is that in their attempt to prove Gandhiji a bourgeois leader by means of a labored fallacious thesis, the Communists came up against an even greater obstacle on their way. In their concern to keep up consistency, they have had to ignore actual events or distort them. They have been at great pains to fit the whole history into the straight-jacket of a petty thesis; little knowing that it will all be in vain.”

3. Erik H. Erikson’s Gandhi

An enquiry conducted by Erik H. Erikson, a Freudian psychoanalyst, during the 1960s in understanding Gandhi’s concept of truth, and origins of non-violence based on Gandhi’s involvement in Ahmedabad textile workers’ case resulted in an enormous work “Gandhi’s Truth”[18]. How could such small and insignificant issue inspire a Freudian psychologist, Erik H. Erikson, to make it a full-fledged subject-matter of his thesis?

Erik H. Erikson, the German-born American psychologist and psychoanalyst, known for his theory on psychological development of human beings, and credited with the coining of the phrase ‘identity crisis’ visited India in 1962, where he ‘had been invited to lead a seminar on the human life cycle’ in Ahmedabad. It was the author’s first trip to India. Freudian psychology normally invokes libidinal forces, sexual aberrations and the conflicts of mind in these areas for explaining a phenomenon. Naturally, the Gandhian disciples mostly ignored this work and the other critics relied upon certain occasional comments such as ‘sadist’ etc., and none did go beyond. Though the method is Freudian and psychoanalytical, and in fact, at certain stages, it explains Gandhi’s childhood, the impact of death of his father, and his act of ‘double shame’ with wife at that momentous time, and the idea of ‘sin’ or ‘the curse’ it carried and his future relations with family – wife and children etc., it also explored how Gandhi succeeded in mobilizing the Indian people both spiritually and politically, as he became the revolutionary innovator of militant nonviolence.

In the year 1918, in the months of February and March, immediately after the Champaran campaign, Gandhi led a strike of textile workers of Ahmedabad for increase of wages by 35% in Ahmedabad through Satyagraha and simultaneously trying for a settlement through arbitration. The Indian Marxists considered the Gandhian model of agitation, Satyagraha, and the method of resolution of industrial disputes through arbitration etc., as “obviously at variance with that is universally followed in trade union movement.”[19] “Desisting the workers and peasants from militant class struggle against the capitalists and landlords, promoting class peace and class collaboration and ultimately to perpetuate the existing society based on capitalist and feudal exploitation – these were what this novelty (of Gandhi) exactly meant. The ingenuity of Gandhian ideology thus lay in the innovation of such an absolutely retrograde theory.”[20]

The method of non-violent resistance is not ‘retrograde’ in any way as the Indian Left thought, but a way forward in the onward march of civilization. The ideological trap of the mid-nineteenth century industrial revolution and its nascent derivatives in the employer-employee relations, and the idea that ‘socialism’ or ‘equality’ can be achieved only through ‘revolutionary violence’ no more hold water, at least in the sense they were understood during Marx’s life. The first victim of any nonviolent action is ‘truth.’ ‘Truth’ and ‘violence’ have certain inherent dichotomy. For Gandhi ‘non-violence’ was an inalienable pair with ‘Truth’. Nonviolence doesn’t necessarily mean absence of revolutionary or militant content. Erikson decided to make Gandhi’s intervention in the Ahmedabad workers’ strike as the focus for some extensive reflections on the origins in Gandhi’s early life and work, of the method he came to call ‘Satyagraha’, or ‘truth force’.

At the end of the work, he makes one peculiar observation: “Gandhi’s and Freud’s methods converge more clearly if I repeat: in both encounters only the militant probing of a vital issue by a nonviolent confrontation can bring to light what insight is ready on both sides.”[21] Psychoanalysis offers a method of intervening non-violently between our overbearing conscience and our raging affects, thus forcing our “moral” and our “animal” natures to enter into respectful reconciliation. He admits[22] that “When I began this book, I did not expect to rediscover psychoanalysis in terms of truth, self-suffering, and nonviolence. But now that I have done so, I see better what I hope the reader has come to see with me, namely, that I felt attracted to the Ahmedabad Event not only because I had learned to know the scene and not only because it was time for me to write about the responsibilities of middle age, but also because I sensed an affinity between Gandhi’s truth and the insights of modern psychology.”

In the Epilogue, journeying a bit beyond the subject matter of inquiry, i.e., the Ahmedabad issue, Erikson attempts to grasp the essence of Dandi March – “March to the Sea” and at the end, a teasing anecdote is retold. Unfortunately no serious Indian author appreciated the significance of this episode of epic proportions that reveals the rebel in Gandhi. “The salt Satyagraha had demonstrated to the world the nearly flawless use of a new instrument of peaceful militancy. May it only be added that after another stay in jail, Gandhi met the Viceroy for the famous Tea Party… After some compromises all around, Gandhi was invited to talks with the Viceroy.… But the Viceroy, Lord Irwin, has described the meeting as ‘the most dramatic personal encounter between a Viceroy and an Indian leader.’ When Gandhi was handed a cup of tea, he poured a bit of salt (tax-free) into it out of a small paper bag hidden in his shawl and remarked smilingly, ‘to remind us of the famous Boston Tea Party’. Moniya and the Empire! … ”[23]

“In a period when proud statesman could speak of a ‘war to end war’; when the super-policemen of Versailles could bathe in the glory of a peace that would make ‘the world safe for democracy’; when the revolutionaries in Russia could entertain the belief that terror could initiate an eventual ‘withering away of the State’ – during that same period, one man in India confronted the world with the strong suggestion that a new political instrument endowed with a new kind of religious fervor, may yet provide man with a choice.”[24]

4. Ashis Nandy’s Gandhi

Colonialism, Ashis Nandy argues, damaged both colonized and colonizing societies. It in fact converted both the aggressor and the victim into the same language. And it was only in Gandhi’s counter-modernity a new language of dissent had emerged. In his ‘The Intimate Enemy’ he says[25]: ‘This work is primarily an enquiry into the psychological structures and cultural forces which supported or resisted the culture of colonialism in British India.’ ‘The rest of this essay examine, in the context of these two process and as illustrations, how the colonial ideology in British India was built on the cultural meanings of two fundamental categories of institutional discrimination in Britain, sex and age, and how these meanings confronted their traditional Indian counterparts and their new incarnations in Gandhi.’[26]

Once the colonizers and the colonized internalized the colonial role definitions and began to speak, with reformist fervor, the language of the homology between sexual and political stratarchies, the battle for the minds of men was to a great extent won by the Raj. ‘Many pre-Gandhian protest movements were co-opted by this cultural change. They sought to redeem the Indians’ muscularity by defeating the British, offer fighting against hopeless odds, to free the former once and for all from the historical memory of their own humiliating defeat in the violent power-play and ‘tough politics’.[27] Obviously, if ksatratej or martial valour was the first differentia of a ruler, the ruler who had greater ksatratej deserved to rule.

All the previous efforts of reformers prior to Gandhi, according to Nandy, like Brahmosamaj, Theosophy, Arya Samaj etc., were some kind of approaches to Christianize Hinduism in terms of a monist tradition. In fact, the beauty or raison d’être of Hinduism is in its plural and rural traditions. The monolithic urban traditions were never its main pillars. Thus, in doing what might be a mental construct they identified the West with power and hegemony, which in turn they identified with a superior civilization. It led to the perception that the loss of masculinity and cultural regression of the Hindus was due to the loss of the original Aryan qualities which they shared with the Westerners.

The psychological process of colonialism i.e., ‘co-optation’ calls for the identification with the aggressor. Gandhi redefined these efforts to organize the rebellion against the British in terms the Hindus as Indians, not as Hindus, and granted Hinduism the right to maintain its character as an unorganized, anarchic, open-ended faith.[28] Gandhi, through his nonviolence, also emphasized the feminine element in the struggle.

Steering through the two dominant understandings of resistance, the Marxist and the Freudian, of class and libidinal forces, Gandhi took the third path of breaking away from the determinism of the both. Nandy[29] says: ‘… colonialism is first of all a matter of consciousness and needs to be defeated ultimately in the minds of men’. This was the way Gandhi defined the idea of ‘swaraj’ since his first serious formulation in Hind Swaraj. ‘As Gandhi was to so clearly formulate through his own life, freedom is indivisible, not only in the popular sense that the oppressed of the world are one but also in the unpopular sense that the oppressor too is caught in the culture of oppression’.[30] What Gandhi arrived at, as conclusion, might be said as: “The alternative to Hindu nationalism is the peculiar mix of classical and folk Hinduism and the unselfconscious Hinduism by which most Indians, Hindus as well as non-Hindus, live.”[31] The specificity of Gandhi’s strategy was mostly a socio-psychological game which had involved the dissenting West in his experiment of Satyagraha – as evident from his actions in SA, and during his ‘Salt Satyagraha.’

5. Anthony J. Parel’s Gandhi

Anthony J. Parel, professor of history in Calgary University, Canada, has attempted to construct Gandhi’s philosophy as a quest for harmony within the major narrative of Hindu philosophy. He tries to explain how Gandhi had reinterpreted four-fold ideas of dharma, artha, kama and moksha – one of the foundations in Hindu philosophy of life in his four books: (1) Hind Swaraj and other Writings (1997); (2) Gandhi, Freedom and Self-Rule (2000); (3) Gandhi’s Philosophy and the Quest for Harmony (2006); and (4) Pax Gandhiana : The Political Philosophy of Mahatma Gandhi (2016). Parel also draws the attention of his readers how Gandhi interpreted and reinterpreted the traditional Hindu texts to give them modern context, and they received secular meaning in Gandhi’s mold. For the sake of convenience, the present work relies only on the text of Gandhi’s Philosophy and the Quest for Harmony.[32]

Parel almost begins with a rare anecdote in Gandhi’s South Africa life[33] when Gandhi, raged with so many doubts about his future course of action in the backdrop of the humiliation he and his fellow Indians were facing while keeping his own life ambition of ‘Moksha’ at the earliest as devote Vaishnavait, he wrote a letter to his guru, Rajchand Bhai. “… In 1894, in an attempt to meet an intellectual crisis that he was experiencing in South Africa, he wrote his famous letter to Rajchandbhai … The letter raised twenty-seven questions regarding such grave matters as the nature of the soul, God, Moksha, the universe, avatars etc. As many as five of these questions were connected with moksha, the fourth purushartha; what it was and how it might be attained. Rajchandbhai’s answer was that moksha was the release of the soul from the state of ignorance and its involvement with the affairs of the world. Mystical knowledge and withdrawal from the world were the chief means of attaining it.”

Gandhi accepted the first part of the advice to read Bhagavad Gita and Yoga Vasishta, but not the second, the part that required the withdrawal from the world. Instead of withdrawing from it, he sought to engage with it. He decided to plunge into politics of South Africa – and the rest is history, writes Parel. Rajchandbhai was disturbed by the fateful turn that Gandhi had taken. He went so far as to warn him – “for the good of his soul – not to get too involved in the politics of Natal.” What could we decipher from the above incident? Probably Gandhi didn’t find the suggestion to individual moksha when the whole society around him was suffering. Moksha, as Gandhi understood, is social and collective, and not individual.

While redefining Hindu philosophical texts according to the dictates of his inner voice, Gandhi also accommodated the Western concepts within his theories. Gandhi considered ‘non-violent nationalism’ as a necessary condition of ‘corporate or civilized life’. He had wholeheartedly embraced the modern idea of nation. According to Parel, Gandhi’s conception of nation was heavily influenced by the civic or liberal notion of nationalism notably that of Guuseppe Mazzini. However, he invokes certain specific Indic terms for constructing his idea. ‘Praja’ is the specific word he used to convey the concept of ‘nation’. The State, according to Gandhi, is an institution necessary for the realization of the values of artha. Gandhi went far beyond Kautilya, says Parel, in identifying the basic functions of the State. For Kautilya, the State’s main function was external expansion through war and internal stability through punishment (danda-niti), but for Gandhi the emphasis is shifted from war to peace and from punishment to rights.

Being religious, according to Gandhi, is a means of achieving the supreme purushartha. While he adhered to the view that religion was necessary for the achievement of our purushartha, he also advocated the view that the State should be neutral in religious matters. In the understanding of Gandhi the neutral does not convey the meaning of irreligious or materialistic State. The State, being rooted in artha, had its own immediate ends, which were not the same as those of moksha.

‘Moksha’ or ‘spiritual liberation’ is the most important issue that tilted the balance of discourse of purusharthas at the end of the first millennium. Gandhi found in the Gita, all that he needed to know about the pursuit of liberation. “The pursuit of moksha supplied the force unifying all of Gandhi’s different activities.”[34] Gandhi approached moksha not as an abstract or imagined goal, but as a goal to be realized in history, in and through action in time. “He fought against the traditional otherworldly approach …”[35]

6. Gandhi in Anarchist Tradition

Any one, at the initial reading of his autobiography, The Story of My Experiments with Truth, would arrive at an idea of Gandhi as primarily a law-abiding citizen. His family legacies, his loyalties to the British rule time and again, and his ambivalences even till the early phases of the Second World War lead us to such derivatives. But Gandhi also makes a parallel contra-reading. All his life was a continuous and long struggle against ‘authority’ – authority of every kind! To cite one, he said once: ‘Freedom is often to be found inside a prison’s walls, even on a gallows; never in council chambers, courts and class rooms.’[36]

Was Gandhi an anarchist or iconoclast internally? In the list of anarchists at wikipedia.org we find the name of Gandhi as one standing with the insignia of “anarchist” along with Proudhon, Mikhail Bakunin, Peter Kropotkin, William Godwin, Emma Goldman, Tolstoy and Bhagat Singh etc. Gandhi’s life provides for humongous evidence of his strained relationship with every ‘authority’ from childhood to his last breath, an inalienable ingredient in anarchist thought. But the problem in the apposition of Gandhi along with anarchists lies in the generally accepted notion that anarchism is deeply interwoven with the culture of violence.

But many studies reveal that even in anarchic tradition of the West there are certain subaltern layers of non-violence. The connecting thread in the anarchist tradition is not violence but the idea of denying ‘authority.’ George Woodcock[37] considered ‘anarchism’ as a doctrine which poses a criticism of the existing society and strives to change it. “All anarchists deny authority; many of them fight against it. But by no means, all who deny authority and fight against it can reasonably be called anarchists. Historically, anarchism is a doctrine which poses a criticism of existing society; a view of a desirable future society; and a means of passing from one to the other.”

There are some basic features common to many, if not all, anarchists: refusal to establish systems, naturalism, deeply moralistic tendencies, anti-historicism, apolitical or anti-political approaches, direct and individualistic action, rejection of or suspicious outlook towards all forms of government or authority etc. Gandhi mostly fits into this description. Very early in Gandhi’s career, Sir C. Sankaran Nair [1857-1934] member of the Central Legislative Assembly of the British Raj had accused Gandhi of being ‘an anarchist’ in an essay titled ‘Gandhi and Anarchy’. At the end of Dandi March on 06.04.1930 – Mrs. Sarojini Naidu hailed him as a “Law breaker”. The Right Hon’ble V.S Srinivasa Sastri also described Gandhi as a “philosophical anarch” who could not be swayed by rational arguments. Gandhi himself described his utopia as ‘enlightened anarchy’. N.K. Bose quoted Gandhi to have said that the State ‘represents violence in a concentrated and organized form. The individual has a soul, but the state is a soulless machine; it can never be weaned from violence to which it owes its very existence’[38] Bikhu Parekh and Partha Chatterjee also recognize Gandhi’s unhappiness with not just the modern State, but the State as such.

The anarchist historian George Woodcock[39] considers: “…..Gandhi’s achievement of awakening Indian people and lending them through an almost bloodless national revolution against foreign rule… was influenced by several of the great libertarian thinkers. His nonviolent technique was developed largely under the influence of Thoreau as well as of Tolstoy, and he was encouraged in his idea of a country of village communes by an assiduous reading of Kropotkin.”

We may also appreciate that the type of community-living experimented by him in name of various ashrams, away from the State, and living within the self-sufficient communities, on certain self-defined terms etc., have also been a peculiar feature of certain anarchist groups. Gandhi was even said to have visited the Trappist monastery in Durban 1895 in this regard. The ‘inner voice’ of Gandhi had constantly driven Gandhi to differ with the established interpretation of conventional ideas, religious texts, political and legal theories generally accepted by the society as belonging to higher rationality.

To Conclude

Gandhi is an enigma most lovable and equally detestable for many. In the Indian tradition of mysticism, he continues to challenge the known interpretations and provides scope for new vistas. Gandhi continues to be known yet unknown, revealed yet concealed and the attraction lies in these contradictions. The systems indicated in this article are only indicative, and Gandhi gives unending scope for further study.

References

- Dr. Omkar Sane, in Nibir K. Ghosh, Sujata and Sunita Rani Ghosh (Eds), Gandhi and his Soul force Mission, Authors Press, New Delhi, p.12

- Shashi Deshpande Abandoning Gandhi The Indian Express (Online) (updated: October 29, 2019

- Larry Collins and Dominique Lapierre, © Larry Collins and Pressinter, S.A., 1975, Freedom at Midnight, Tarang Paper Backs (Vikas Publishing House Pvt Ltd), p.262-3

- Doke, Joseph J., M.K.Gandhi, An Indian Patriot in South Africa, 1909, Indian Chronicle, London

- Shat Darsanas in the traditional Hindu philosophy are six systems of approach to truth – Sankhya, Yoga, Nyaya, Vaiseshika, Mimamsa and Vedanta

- Romain Rolland, Mahatma Gandhi, Translation from the French by Catherine D. Groth, © 1924/2004 Publications Division, Govt. of India, New Delhi, p.1

- Ibid, p.18-19

- Ibid, p.40

- Ibid, p.63

- Ibid, p.109

- Pannalal Dasgupta, Revolutionary Gandhi, Earthcare Books, Kolkata, 2011

- Forward to the Bengali First Edition, Pannalal Dasgupta, Revolutionary Gandhi, p. ix.

- Ibid, p. 443

- Ibid, p. 15

- Ibid, p. 78

- Ibid, p. 329

- Ibid, p. 475

- Erik H. Erikson, Gandhi’s Truth – On the Origins of Militant Nonviolence, W.W. Norton & Company Inc. New York 1969

- Sukomal Sen, Working Class of India, (1977, 1997) K.P.Bagchi & Company, Calcutta, p.133

- Ibid, p.137

- Erik H. Erikson, op. cit, p.439

- Ibid, p.439-40

- Ibid, p.448

- Ibid, p.391

- Ashis Nandy, The Intimate Enemy, Oxford (1983), Preface, p.xvi

- Ibid, p.4

- Ibid, p.8-9

- Ibid, p.25-26

- Ibid, p.63

- Ibid, p.63

- Ibid, p.104

- Anthony J. Parel, Gandhi’s Philosophy and the Quest for Harmony (2006), Cambridge University Press, New Delhi

- Ibid, p.14

- Ibid, p.177

- Ibid, p.178

- Collins and Lapierre, op., cit. p.50

- George Woodcock, Anarchism: A history of Libertarian Ideas and Movements, © 1962 World Publishing, New York, p.9

- Parel, op. cit., p.52

- Woodcock, op. cit., p.234

(Dr. A. Raghu Kumar is a practising Advocate in Labor and Employment law in Hyderabad, and the Director of The Centre for Critical Juridical Studies.)