Annus Horribilis 2021 Leaves India Frayed, but Fight Must Continue

Smruti Koppikar

If there is an annus horribilis gravis for India, this must be it.

The classic annus horribilis (year of disaster) was, of course, last year when the SARS-CoV-2 virus whipped the world around but, for India, this year was worse by a far mile. It not only unleashed the full force of the devastating virus which claimed millions of lives on a scale that the country had not witnessed for a century but it also brought forth the toxic mix of a sluggish economy and hate politics that threatens India’s soul.

And what of our hope that hung by a thread when we bid goodbye to last year? That thread is frayed, fraying by the day, and seems more slender than it has been in many decades.

On December 25, which the Narendra Modi government rechristened as Good Governance Day in 2014, Home Minister Amit Shah heaped praise on his boss, Prime Minister Modi, for tirelessly working for poor and marginalised Indians. Shah did not intend it as dark humour but it is the darkest version possible.

For, as 2021 folds up, governance is barely visible – India’s tryst with the pandemic leads to apprehension given the shocking mismanagement of the second wave in early 2021; signs of economic recovery are few and far between, more Indians are poorer than before, and India’s descent into the communal cauldron gathers momentum every passing day. All this on Modi-Shah’s watch. The chaotic democratic republic looks more like a poorer Hindu Rashtra.

PM of Hindu India

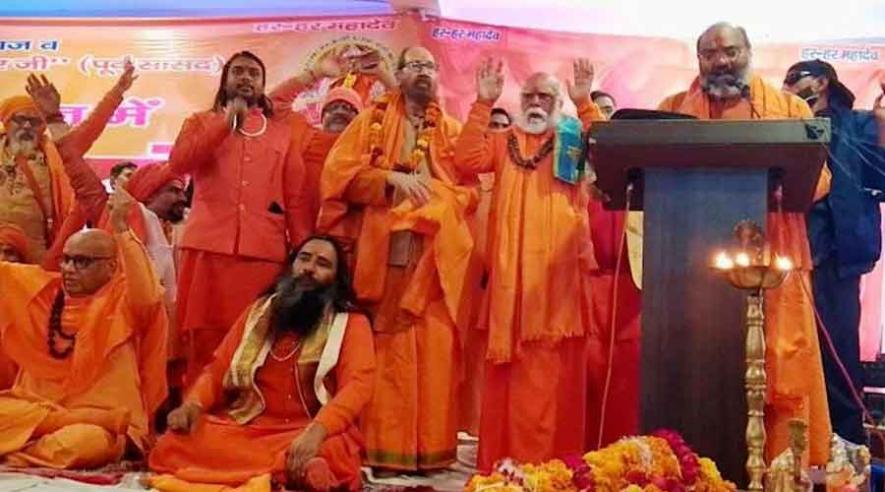

India is in the grip of a deliberately drummed-up hate storm. Make no mistake about it. The Hindu Dharam Sansad, more correctly called the Haridwar Hate Assembly, unmasked the Hindutva project. Self-appointed men and women of god spat out their hate towards minorities – especially Muslims – and called upon those gathered to pick up arms, prepare to kill and die for Hindu nation, asked the Army to replicate Myanmar (violence against Rohingyas) in India, and spoke of assassinating former Prime Minister Dr Manmohan Singh. A television anchor read out a similar pledge, and minor school children were seen taking this pledge in videos that went viral. Yati Narsimhanand Giri, the chief organiser of the Dharam Sansad, has been reportedly under the police scanner for previous hate speeches. Yet, he is a free man presiding over genocide calls and taunting the law. In 2020, his Dharam Sansad had preceded the riots in North East Delhi.

It is not an accident that the pledge to rid the republic of nearly 200 million citizens is openly flaunted, fired-up groups vandalise churches during Christmas and burn Santa Claus’ effigy, determined Jai-Shri-Ram shouters prevent Muslims from holding Friday namaz at a designated public ground, and south Bengaluru’s Lok Sabha MP demands that minorities be brought back to their “mother religion” at a time when the Prime Minister repeatedly alludes to Aurangazeb (and his heirs) to be taken on and vaunts his presence at Hindu dharmic rituals.

The fount of hate is in full flow in its hydra-headed manner. It must delight the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh whose Hindutva project has been given space and protection by the BJP. Should the Prime Minister not live by his religion, is a question often asked. No one denies him that right. His predecessors too visited places of worship but the difference must be called out; they went to different religious places while Modi is obviously partial to temples, save an occasional gurudwara.

In holding his silence over the continued verbal and physical attacks on minorities, by not condemning the Haridwar genocidal calls and kill-Muslim pledges, he makes it clear to Hindutvawadis every day that he should be trusted to give shape to their dream of Hindu Rashtra. In 2021, through his words and acts, he left no stone unturned to repeatedly hammer home the message that he is a Hindu Prime Minister or the Prime Minister of Hindu India.

New Normal and Pushback

Hate expressed in vicious and violent terms towards Muslims and Christians, hate-filled catcalls made at women from opposing political parties at election rallies, hate-acts against Dalits and women, venomous hate expressed in lynching and beating incidents now filmed and circulated as proof of Hindu dominance are the new normal as much as living with Covid-19 is. Hate flows from many corners, hate is loud and chest-thumping, and hate is political capital. And hate dares the judicial system to take action and laughs at its evident surrender. Did you not see that video of Haridwar Hate Assembly’s godwoman and godmen with a cop, laughing together?

The phrase ‘new normal’ is severely inefficient, inexpressive and tired. Our normal was bad enough – there was communal strife and anti-Dalit violence – but the new normal is far worse. Hate became the calling card of 2021, and India went several rounds down the spiral.

Somewhere in this majoritarian hate storm are little islands of acceptance, tolerance, accommodation, and some pushback. As many as 76 Supreme Court lawyers wrote to the Chief Justice of India to take cognisance of the hate speeches at Haridwar Members of All India Professional Congress (AIPC) filed cases against the hate speakers. Protests against and condemnation of the Haridwar hate speeches were organised in several places.

In Gurugram, where Muslims were stopped for weeks together from Friday namaz, Sikhs opened the gurudwara to let them pray in peace. When 12 shows of comedian Munawar Faruqui were cancelled across India’s cities under pressure from right-wing groups, which threatened to vandalise venues where he was scheduled to perform, the state Congress unit took the lead. They provided him with a prestigious stage in south Mumbai and got the Mumbai Police to ensure an event-free evening.

These are significant pushbacks and they send out an important message of solidarity. But commendable as they are, they cannot be enough against the tsunami of hate. These are the efforts of individuals or small groups and collectives. The Hindutva organisations which peddle hate and terror are non-state actors and enjoy silent acquiescence of the State, as has been evident on more than one occasion.

It is a most unequal battle but has to be fought. Those who push back in words and deeds may not be able to stop all hate and terror that flows from it, but they send out the message that hate will be challenged and taken head-on. In a frayed fabric, all such patches are welcome.

Pandemic and Economics Fall off Map

The Modi government’s gross and shameful mismanagement of the COVID-19 pandemic when the second wave ravaged India is, by now, well documented. Through the horrific days and nights in April-May-June 2021 when Indians struggled and begged for hospital beds or oxygen cylinders, when mass funerals defined the summer and scores of bodies floated on Modi’s beloved river Ganga, India’s Prime Minister was not seen or heard. Likewise, India’s Home Minister and Health Minister. Modi’s ratings, which never seem to suffer from any of his missteps, dropped, showing the extent of people’s anger. Inexplicably, that anger seems to have dissipated as the year closes.

Distraught Indians then had only their own networks, largesse of fellow citizens and do-gooders like the Youth Congress workers to lean on. Social media platforms became the go-to places for people caught in the medical emergency. The YC’s national president BV Srinivas and his band of emergency workers in war rooms, approachable and responsive, were infinitely more visible and in control than the Government of India in those weeks. States with non-BJP governments, especially Maharashtra and Kerala, which reported high COVID-19 numbers, were targeted by the Centre; the BJP as opposition in Maharashtra also chose those opportune months to attempt to pull down the Uddhav Thackeray-led government.

India’s economy, which seemed to be in free fall since Modi unveiled the demonetisation disaster in 2016, shuddered through the pandemic. Despite repeated assurances from Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman that “green shoots” were visible, the indices stubbornly refused to show recovery. The green shoots, such that are visible, are barely enough. Even when the economy recovers, it is likely to be uneven, say analysts.

Jobs are harder to find, unrelenting inflation burning holes in household budgets, high fuel prices a cruel joke even among Modi’s fans, children dropping out of the education system which itself is under attack from Hindutva revisionists, more Indians going hungry to bed than before, the value of senior citizens’ savings shrinking by the month, worrying trend of exchange rate of currency, and the 2A (Ambani and Adani) consolidation approach of the government which takes crony capitalism to a nauseating peak are all marked on the 2021 calendar.

Look at it any which way, and this has been an annus horribilis gravis (seriously horrible year) for India. Only the Hindu Rashtra dreamers would rejoice at the end of this year. Given the many omissions and commissions, Modi-Shah should have reflected and done course corrections, but Shah is more his party’s election chief than India’s Home Minister and Modi more a performer for the cameras than Prime Minister.

It’s hard to embrace hope or look for alternatives as we welcome 2022, but we must.

(The author, a senior Mumbai-based journalist and columnist, writes on politics, cities, media and gender. Courtesy: Newsclick.)

❈ ❈ ❈

Another article in SabrangIndia, “2021: The Year of Evictions” adds:

On September 9, 2021 the Housing and Land Rights Network (HLRN) announced that over a quarter of a million people i.e., 2.57 lakh individuals were evicted in India during the Covid-19 pandemic. It estimated around 21 people were evicted from their homes every hour between March 2020 and July 2021.

Further, over 24,400 homes, affecting over 169,000 people were demolished by authorities from January 1 to July 31, said the report. Families struggled to keep their young ones alive without a roof over their heads and a global pandemic raging around them. Especially tribal families in Assam survived widespread demolition by the BJP-regime that has its eyes on the approaching election.

Anticipating many more such trials ahead, CJP Team compiled a legal resource that showcases how Courts continue to step in to protect and emphasise the right to live without forced evictions and the right to housing. Similarly, former National Human Rights Commission (NHRC) Chairperson Justice Arun Mishra spoke during a webinar on July 31 about why indigenous communities should not be evicted without the settlement of their claims related to land rights.

However, as children and elderly alike live amidst the ruins of their former homes nearing the end of 2021, it is important to take stock of how many people’s lives were turned upside down due to illegal and forced evictions.

Assam

This is possibly the worst affected state when it comes to evictions. Thousands of people, most of them Bengali-speaking Muslims and Hindus were dubbed “encroachers” and evicted from their homes across the state.

The first incident occurred on May 17, 2021 when as many as 25 families were removed from their places of residence in Dighalichapori, Laletup, Bharaki Chapori, Bhoirobi and Baitamari villages of Sonitpur district. All of these are flood-prone areas near the river and the evictions took place amidst a raging Covid-19 pandemic. On June 6, as many as 74 families from Kaki in Hojai district were evicted on from their homes. Roughly 80 percent of this population is Muslim. The following day, nearly 50 families were evicted from Dhalpur, Phuhurtuli in Darrang District with more evictions planned, leading to an outcry in Sipajhar. On August 7, as many as 61 families were evicted from Alamganj in Dhubri district, where 90 percent of the population is Muslim. Later, on September 20, around 200 families evicted from Fuhuratoli, Dhalpur in Darrang district.

However, the worst instance of hate-induced eviction came on September 23 when hundreds of families were evicted from their homes in the same area with notices served the previous night via Whatsapp! What’s worse, when these people protested, police opened fire upon them. Two people including a 12-year-old boy were killed in this incident.

A day before the forced removal, residents of Dhalpur No. 2 and 3 received over 600 notices detailing the eviction schedule from 10 AM the following morning. Horrified by the sudden upheaval in their lives, around 2,500 villagers protested outside the eviction area demanding more time and a designated place for rehabilitation. Officials agreed at first however, on returning home residents found armed police personnel outside their houses. Officials fired guns and brutally assaulted children and adults alike.

The violence received international coverage. The government claimed 960 families were evicted till that day while village heads put the number at 963. In severe condemnation of the attack on unarmed locals, CJP moved the Gauhati High Court and demanded justice for the evicted families.

Worse still, CJP’s on-ground Team learnt on November 5, that at least three infants from these families died: 5-day-old Rajib Ahmed, 2-month-old Rohim Ahmed and a year old Akhi Aktara. The cause of death is still unknown.

Even five years after the incident, the State Ministry of Revenue and Disaster Management is still asked about the details of the post-2016 evictions. Thus, ever since the BJP came in power in Assam, families have been condemned as “encroachers” and cleared from thousands of bhigas of land, leaving only a few dozen families with land for relocation purposes.

Most recently, the Assam government evicted nearly 3,000 people living in over 1,000 hectares of land inside the Lumding Reserve Forest in Hojai district from November 8. Another 1,050 people were evicted from the Karbi Anglong district during a drug-related operation. The administration claimed the encroachers were engaged in the drug trade.

Hindustan Paper Mills

The eviction saga in Assam does not simply end with land claims and xenophobia. Around September 7, the authority auctioning two Hindustan Paper Corporation Ltd. (HPCL) paper mills in Nagaon and Cachar, served an eviction notice to the mill’s employees amidst the Covid-19 global pandemic and successive floods.

The notice robbed the roof off 900 people. Earlier, associations of officers and employees moved court challenging the liquidation of the mills. On June 16, the Court dismissed the e-auction of the mills. Yet, the authority persists with evicting workers and officers from the mill. Read more here. However, later the administration announced a relief package where it agreed to clear the pending dues of workers and took over assets of the now defunct mill.

Madhya Pradesh

The peaceful lives of Bhil and Barela tribal communities in Khandwa were thrown into turmoil on July 10 when a mob allegedly supervised by local police and JCB vehicles destroyed their small hamlet. As many as 40 Adivasi families now live amidst the ruins of their village without a roof on their heads. The destroyed settlement, now a mixture of rubble and dirt, is where once stood homes, and fields of crops.

Over 200 people were attacked and chased out of their homes even as the Covid-19 pandemic continued unabated and heavy rains lashed the area during the monsoon. This despite a High Court order that barred demolition and eviction of Negaon-Jamniya villages until July 15.

130 quintals of food grains, Rs. 63,800 in cash, a shop worth Rs 80,000, jewellery worth Rs.12,000, five cycles, four mobile phones, over 300 chickens, 16 goats and one calf were either destroyed or looted from villagers. Another calf was killed when JCBs were tearing down the huts of the local residents.

Following the incident, hundreds of Adivasis demonstrated outside Khandwa SP’s office to demand the release of six people arrested during the incident. Later, CJP Team also worked with the Jagrit Adivasi Dalit Sangagthan to organise a press conference wherein the residents could voice their grievances to the media. Read more here.

Meghalaya

The state government on October 30 took over the land that accommodated residents of the Dalit Sikh workers settlement Punjabi Lane (Harijan colony). Officials paid local chieftain Syiem of Hima Mylliem Rs. 2 crore for the land spread over 12,000 sq meters.

Government records identified 184 employees and their families as legal settlers, including 128 employees of the Shilling Municipal Board (SMB) and 56 workers from other departments. These families are eligible for relocation to staff quarters. However, the total strength of this settlement is as much as at least 300 families of Dalit Sikhs whose ancestors were brought by the British to work as conservancy workers.

It is worth questioning why families that moved out of their traditional area of work and established small shops or entered the service industry were suddenly deemed “illegal settlers”. Read more here.

Haryana

The HLRN’s ‘Forced Evictions in 2020’ report that also covered the first half of 2021 stated that the Faridabad Municipal Corporation demolished at least 12,000 houses belonging mostly to daily-wage workers in Khori Gaon, Haryana between July and August. The allegedly forceful removal left 10,000–15,000 families homeless as the rainy season began. Pregnant and lactating women, new-born babies, children, older persons, and persons with disabilities alike were thrown out on the streets since the officials did not come up with a comprehensive rehabilitation plan.

As a result, many affected persons continue to live in the rubble of their former homes, much like the Khandwa Adivasis.

Meanwhile, Gurugram authorities too displaced a large number of labourers and migrants between March and June. The Gurugram Metropolitan Development Authority and the Municipal Corporation of Gurugram destroyed 60 houses in Chakkarpur and Sikanderpur, in June to create an ‘urban forest’. In March, the Municipal Corporation of Gurugram demolished 2,500 houses in Wazirabad to build a sports stadium. Then the Haryana Shahari Vikas Pradhikaran demolished 350 homes, mostly of nomadic families, to construct a school.

Delhi

The report went on to focus on national capital Delhi where the central government carried out multiple home demolitions between March and July. Once again ignoring Covid-19 restrictions, officials like those from the Delhi Development Authority (DDA) demolished 50 houses in Yamuna Khadar, without prior notice, allegedly to implement National Green Tribunal orders to remove all ‘encroachments’ along the floodplains. With nowhere else to go, the community once again chose to stay amidst the rubble. Almost 135 families living near Shastri Park also became homeless in February on the basis of the same order.

Later, another 70 Usmanpur houses were demolished in March. When the people tried to reconstruct dwelling units in the area, the 20 temporary structures were again destroyed in June. In July, 15 Rangpuri Pahadi houses were destroyed even though some people had proof of residence. During the monsoon, the DDA took down 300 houses of daily-wage earners in Ramesh Park over a period of four days.

Further, in June, the DDA demolished tents of homeless persons living in Urdu Park, as part of a ‘city-beautification’ drive that forced at least five families to live on the pavement. Due to the harsh conditions, rain and lack of healthcare, one of the families lost their 11-day-old baby in July.

Uttar Pradesh

As per HLRN data, around 2,850 families from five villages of Gautam Buddha Nagar district were evicted to build the Noida International Greenfield Airport between April and July. While the first phase of the project began, affected families resettled at Jewar Bangar village, at a distance of 11 km.

Similarly, Varanasi district administration evicted over 100 low-income families in January for the smart city project. Once again, there was no plan for rehabilitation from the side of the officials.

Gujarat

The HLRN reported demolition of 130 houses in Fatehwadi for various infrastructure projects in April. This happened after 90 homes were destroyed in Juhapura, Ahmedabad, in January. Then in March, the Ahmedabad Municipal Corporation along with Indian Railways officials evicted 350 people for the construction of the Mumbai–Ahmedabad High Speed Rail Corridor project.

Other demolition as per the HLRN

Forest department officials in South Kashmir’s Shopian district demolished 24 houses of the Gujjar community as per the Jammu and Kashmir and Ladakh High Court order to remove “encroachments”. However, residents accused the officials of manhandling and injuring them.

Jharkhand’s Jamshedpur district administration and police razed 200 homes in Khasmahal to vacate government land in March 2021. Reportedly, the police detained a few people who were protesting against the demolition, said HLRN.

In Karnataka, the Slum Development Board destroyed over 200 houses in Mysore for the expansion of railway tracks in April – the peak month of the second wave of Covid-19.

Similarly, the Tamil Nadu Slum Clearance Board demolished 130 houses in Arumbakkam, Chennai in July, for an Integrated Cooum river eco-restoration project. In Coimbatore, 141 houses were demolished along the Selvampathy tank bund as part of an ‘encroachment’-removal drive.

In Telangana, the High Court issued an order that led to the South Central Railway demolishing 120 houses constructed on its land in Medhara Basti, in July. Lastly, the Mangrove Conservation Cell in Mumbai demolished 250 houses in Borivali in April and took down 450 huts in Chheda Nagar in February.

(Courtesy: Sabrang India)