Brian Richardson

(This is a tribute to Bob Marley, the world renowned revolutionary Jamaican singer, songwriter and musician, who died on 11 May, 1981 at the young age of 36. This song by him, recorded in 1976, becomes even more relevant today when there is a global uprising against racism.)

War

Bob Marley

Until the philosophy

Which hold one race superior and another

Inferior

Is finally

And permanently

Discredited

And abandoned

Everywhere is war

Me say war

That until there no longer

First class and second class citizens of any nation

Until the color of a man’s skin

Is of no more significance than the color of his eyes

Me say war

That until the basic human rights

Are equally guaranteed to all

Without regard to race

Dis a war

That until that day

The dream of lasting peace,

World citizenship

Rule of international morality

Will remain in but a fleeting illusion to be pursued,

But never attained

Now everywhere is war

War

And until the ignoble and unhappy regimes

That hold our brothers in Angola

In Mozambique

South Africa

Sub-human bondage

Have been toppled

Utterly destroyed

Well, everywhere is war

Me say war

War in the east

War in the west

War up north

War down south

War war

Rumors of war

And until that day,

The African continent

Will not know peace,

We Africans will fight we find it necessary

And we know we shall win

As we are confident

In the victory

Of good over evil

Good over evil, yeah

Good over evil

Good over evil, yeah

Good over evil

[“War” is a song recorded and made popular by Bob Marley.. It first appeared on Bob Marley and the Wailers’ 1976 Island Records album, Rastaman Vibration.]

◆◆◆

Bob Marley: Roots Revolutionary

Brian Richardson

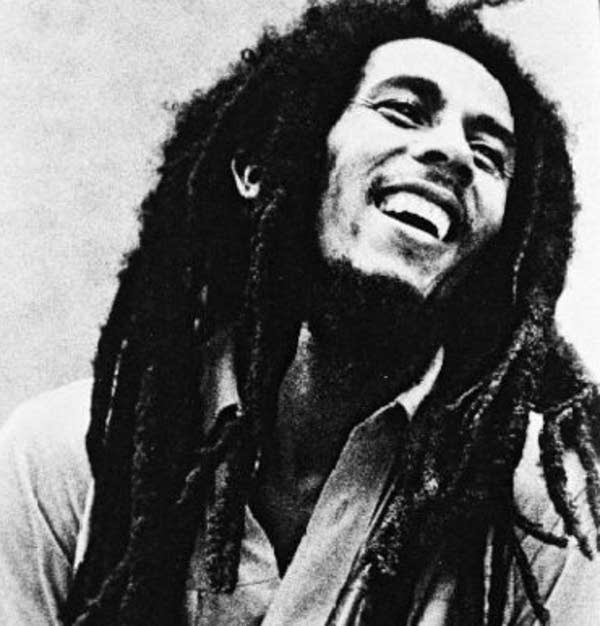

Legend is the title of the one reggae album that every broad-minded progressive is guaranteed to have in their record collection. The word has become somewhat devalued through overuse, but few terms could more aptly describe the Jamaican music star Bob Marley. His iconic status is cemented by the fact that he died at the tender age of 36. Since then, like another ‘soul rebel’ Che Guevara, his handsome face has been immortalised on the T-shirts and bedroom posters of millions of young people.

The anguish and the optimism

It is a fitting tribute that the extraordinary performance of Marley and his band the Wailers at the Rainbow theatre in London in 1977 was chosen by the New York Times for inclusion in a time capsule to be opened in 1,000 years time. Similarly, Time magazine declared Marley’s Exodus its album of the 20th century. He took reggae, a musical form indigenous to Jamaica with a heavy emphasis on a rhythmic interplay between drums and bass guitar, and popularised it across the world. More importantly, in the heady political atmosphere of the 1960s and 1970s he articulated the anguish and the optimism of the oppressed and exploited in a way that had universal appeal. The titles of some of his most famous releases alone – ‘War’, ‘Revolution’, ‘Burnin’ and Lootin’, ‘Get Up Stand Up’, ‘Rebel Music’, ‘Uprising’ – surely make him worthy of closer consideration.

In his outstanding study of Marley’s songwriting, Kwame Dawes suggests that his ‘talent is as inexplicable as the talent of any of the great artists of all time. It is pointless trying to explain it.’

Dawes is right to describe Marley as a ‘lyrical genius’, but like all artists he was a product of his time and it is therefore possible to understand at least a part of his brilliance by reference to the world in which he lived.

Jamaica is a place of breathtaking natural beauty. However, it is also a country steeped in a history of violence and brutality. The pioneer of this was Christopher Columbus who ‘discovered’ the island in 1494 and proceeded to either slaughter the Arawak population that already lived there or sell them into slavery. From 1517 onwards the island was increasingly populated by transported slaves. Britain seized control from Spain in 1655 and set about an even more intense process of exploitation. By the end of the 18th century over 300,000 slaves inhabited the island and by the time slavery ended in 1839, 42 percent of sugar exported to Britain came from Jamaica. It was a lucrative business for those who owned and controlled this wealth. For the captive population, though, it was a life of unmitigated misery. The cruel hypocrisy of this colonial rule is a constant theme of Marley’s work.

Despite the masses’ eventual release from captivity this wretchedness continued and led to a number of uprisings – including the famous Morant Bay rebellion of 1865 led by Paul Bogle, who was hanged after his capture.

It was into this society at the fag end of British imperial rule that Robert Nesta Marley was born on 6 February 1945. His father was a white British naval officer who Marley never knew, his mother, Cedella Booker, a poor cleaning woman in her teens. As a child growing up in Trench Town he experienced the crippling poverty that was the legacy of British imperial rule.

Jamaica finally gained its independence in 1962. However, an economy now based on bauxite mining and tourism brought little prosperity or equality. By the middle of the 1970s 80 percent of the island’s wealth was owned by just 2 percent of the population and 24 percent of adults were unemployed. Despite having his first number one hit in Jamaica in 1964, Marley was one of the many trapped in this cycle of poverty. Over the next decade he earned barely £200 from his music and was forced to work as a welder and hotel janitor. It was not until wealthy white Jamaican Chris Blackwell offered the Wailers a lucrative contract with Island Records in 1972 that fame and fortune came Marley’s way.

Even at the earliest stage of his career Marley and his fellow Wailers Peter Tosh and Bunny Wailer articulated the anguish of Jamaican society. The number one record ‘Simmer Down’ directly addressed the stifling alienation felt by youth at a time of few opportunities.

In some senses Bob Marley is difficult to fathom. He was notoriously hard to understand in conversation. This encouraged speculation that a man so apparently incoherent couldn’t have written his own lyrics. In truth his indecipherability had more to do with his heavy dialect and the prodigious amounts of ganja that he smoked! More particularly, the difficulty analysing Marley lies in the apparently contradictory philosophy that inspired his writing. He vehemently denied any interest in what he termed ‘politricks’, proudly proclaiming that his belief system was religious. His religion was Rastafarianism, a bizarre cult whose followers declared that the Ethiopian emperor Haile Selassie (born Ras Tafari) was the living god, or ‘Jah’ as they called him.

This claim was difficult to maintain for a number of reasons. Firstly, neither Selassie himself nor his family ever accepted such an ultimate accolade, though he was happy on occasion to bask in the adulation it afforded him. Secondly, his 40-year rule was characterised by nepotism, personal cowardice and tyranny. Finally and perhaps most conclusively, he died in 1975, thus giving the lie to his followers’ claims of his immortality. Rastafarians were subjected to disdain, harassment and exclusion in Jamaica. Yet there is a real sense in which, given the island’s tortured history, we can understand the sect’s appeal to the young Marley. Writing in 1843 in response to fellow German philosopher Hegel, Karl Marx argued: ‘Religious suffering is at one and the same time the expression of real suffering and a protest against real suffering. Religion is the sigh of the oppressed creature, the heart of a heartless world and the soul of soulless conditions.’

In short, religion provides a framework within which a believer can understand their suffering and take some comfort from the hope that as long as they maintain their faith a better world awaits them in eternity.

Rastafarianism is founded on a belief that the promised land can be found in the here and now, on earth, in Africa. Rastafarians incorporated ganja into their belief system, regarding it as a sacred herb that provides followers with nourishment and ‘upliftment’.

There is also a distinctly political element to the origins of Rastafarianism. The sect stems from the Back to Africa teachings of black nationalist leader Marcus Garvey. In 1927 Garvey, who was himself born in Jamaica, declared that a saviour of black people was coming. When Selassie became the leader of Ethiopia in 1930 he appeared to be the living embodiment of that being.

Corrupt and violent patronage

Marley was an immensely political figure despite his protestations to the contrary. He was certainly regarded as such by those jockeying for power and influence in Jamaica. By 1976 he was well on his way to international stardom. As a result he was also becoming an increasingly influential figure in Jamaican society. In November of that year, two days before the Wailers were due to perform at a rally organised by the Peoples National Party (PNP) during a fractious general election campaign, Marley and his wife Rita were shot and wounded. Two years later he famously brought Michael Manley and Edward Seaga, the respective warring leaders of the PNP and the Jamaican Labour Party, together at a One Love Peace concert in Kingston. He was probably the only person who could have achieved this in a country dominated by corrupt, divisive and often violent patronage.

In April 1980 he played at the celebrations marking the end of white supremacist rule in Rhodesia. His song ‘Zimbabwe’, celebrating the new black-led nation, features on the album Survival. This release, which carries the flags of all Africa’s countries on the sleeve, is a clear and uncompromising call for African unity.

Marley was certainly a deep thinker with a clear understanding of Britain’s colonial barbarity:

They live a life of false pretence every day

These are the big fish who always try to eat down the small fish,

…they would do anything to materialise their every wish.

He railed against injustice and inequality, incorporating the words of a brilliant speech Selassie had delivered at the United Nations in 1963 into his song ‘War’. He distrusted politicians: ‘Never make a politician grant you a favour. They will always want to control you forever.’ He hated the police – ‘uniforms of brutality’ – and he was clear which side he was on: ‘If you are the big tree, we are the small axe, coming to cut you down.’

The militant message and call to arms was mixed with calls for peace and love and an ultimate belief that faith in Jah would lead to the exodus of his followers from Babylon to salvation in Ethiopia. Music itself was a key means by which this transformation and transportation would occur. Hence Marley implores his comrades to:

Emancipate yourselves from mental slavery

None but ourselves can free our minds…

Won’t you help to sing these songs of freedom

Cause all I ever had, redemption songs.

In the wake of his shooting Marley fled to Britain. During his exile he found a degree of tranquillity during which he recorded a couple of more reflective albums, Exodus and Kaya. His separation from the day to day struggle helps explain this and allows us to forgive the atrocious ‘Three Little Birds’, especially as he rediscovered his appetite for beautiful love songs such as ‘Turn Your Lights Down Low’ and ‘Waiting in Vain’.

While in Britain Marley identified with and celebrated the creativity of the new wave music that exploded onto the scene in the late 1970s. On Exodus he imagines a ‘punky reggae party’ at which the Wailers would be joined by ‘The Damned, The Jam, The Clash and Dr Feelgood’, but ‘no boring old farts’. Sadly Marley’s premature death ensured that what could have been the greatest punky reggae party has instead become one of the most poignant missed opportunities.

Rock Against Racism (RAR) was launched in Britain in the wake of Eric Clapton’s drunken declaration of support for the racist bigot Enoch Powell at a gig in 1976. RAR founders Red Saunders and Roger Huddle had been particularly incensed by the fact that Clapton had recently revived his career with a cover of Marley’s ‘I Shot the Sheriff’.

In 1982 Red Saunders went to Jamaica to shoot a photo story on the various music labels for the Sunday Times. He was shown around the Tuff-Gong studios by Marley’s backing singers the I-Threes. When he went into Bob’s old office a copy of the letter that he and Huddle had written to the New Musical Express, which launched RAR – and which famously declared, ‘Who shot the sheriff Eric? It sure as hell wasn’t you!’ – was mounted on the wall. The I-Threes informed Red that Bob had welcomed the letter and shown great interest in RAR. To this day Red and Roger rue their reluctance to follow their instincts and invite Marley and John Lennon to headline RAR’s first carnival.

Barely a year after the Zimbabwe concerts Marley was dead, killed by cancer. He had amassed an estimated £30 million fortune. He was far too young, but at least he gave the world a wonderfully defiant, sincere and spiritual music, which inspired others including his former partners Tosh and Wailer, compatriots Burning Spear and Black Uhuru, and here in Britain the likes of Steel Pulse, Aswad and dub poet Linton Kwesi Johnson.

In the 38 years since his death nobody has come close to matching Bob Marley and no amount of printed words can do justice to the pride, passion and poignancy of his music.

(Brian Richardson is a British socialist activist, and author.)