The Chief Justice and the Father of the Nation

Ramachandra Guha

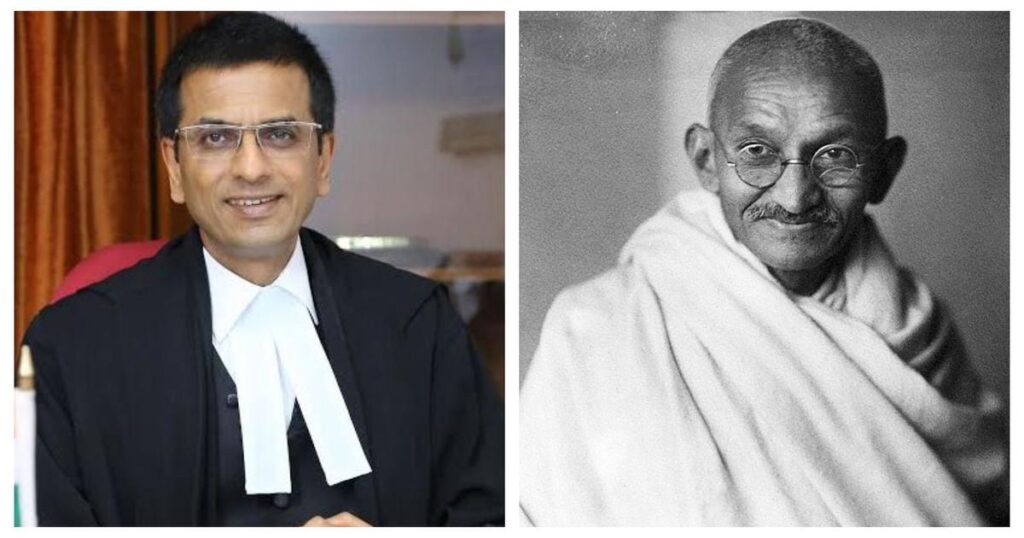

Like most of my readers, I begin the day by reading the newspapers, in my case online and then in print. On Sunday, January 7, the first paper I read was the web edition of the Indian Express, and the first story I read was the lead for that morning, which reported on a visit by the chief justice of India, DY Chandrachud, to some Hindu temples in Gujarat, including the celebrated shrine in Somnath. The photograph accompanying the story captured the chief justice and his wife reverentially praying in an equally hallowed place of worship for Hindus, the Dwarkadwish temple.

The Indian Express story contained these lines: “Justice Chandrachud said that he had started visiting various states ‘inspired by the life and ideals of Mahatma Gandhi’ to understand challenges facing the judiciary and to identify solutions, adding that his two-day Gujarat visit was part of the same effort.” The reference to Gandhi intrigued me, since – though I am not a lawyer, still less a judge or chief justice – I have spent many decades studying the life and legacy of the Mahatma.

As is well known, on his return from South Africa Gandhi spent a whole year travelling around the country by train, in a bid to get to know it adequately before commencing a public career. In later decades, while working as a social reformer and a politician, he continued to travel all across India – usually in a third-class railway compartment, but also by car, bullock-cart, and, not least, on foot.

Gandhi would have approved of any Indian – rich or poor, famous or obscure, man or woman – seeking to get to know the country and its people better. But what would he have thought of a serving chief justice making public visits to temples, and getting himself photographed and giving interviews about it in the process?

Gandhi himself virtually never went to a Hindu temple – one of the very few exceptions he made was when he visited the Meenakshi temple in Madurai in 1946, after the shrine had finally, belatedly, allowed Dalits to enter its premises. Though Gandhi described himself as a Hindu, his chosen mode of worship was the inter-faith meeting, held on open ground, where Hindus, Muslims, Parsis, Sikhs and Jains and Christians would pray together, with verses of all their scriptures being read. That was his original and deeply moving way of affirming the principle that India belonged to all faiths equally.

Gandhi may not have wished or expected the chief justice of India to follow him and hold inter-faith prayer meetings (whether in the grounds of the Supreme Court, or anywhere else). And nor should we. One of the most devout Hindus I myself know is a former chief justice of India, who begins his day and ends it with prayer and meditation. This he does, however, in a puja room in his own house. It is quite possible that, in his distinguished (and still admiringly spoken about) tenure, this former CJI occasionally visited temples, but surely never in a public manner, offering himself to be photographed. And he would certainly not have done it at a time like this, ten days before the inauguration of the new temple in Ayodhya, in a spectacular ceremony that shall be a mark not so much of Hindu piety, but of Hindutva majoritarianism.

The Indian Express story also contained some other remarks made by the chief justice, which bear thinking about. I quote: “Referring to the dhwaja [flag] atop Dwarka and Somnath temples which he visited during his two-day visit to Gujarat, the CJI said, ‘I was inspired this morning by the dhwaja at Dwarkadhish ji, very similar to the dhwaja, which I saw at Jagannath Puri. But look at this universality of the tradition in our nation, which binds all of us together. This dhwaja has a special meaning for us. And that meaning which the dhwaja gives us is – there is some unifying force above all of us, as lawyers, as judges, as citizens. And that unifying force is our humanity, which is governed by the rule of law and by the Constitution of India,’ he said.”

I presume the chief justice has been accurately quoted. If he has, I must say, with due respect, that his interpretation of our ancient and modern history does not stand critical or indeed moral scrutiny. For it is emphatically not the case that the dhwaja which has traditionally flown above Hindu temples has served to bind “all of us together” in a common humanity. In fact, for the bulk of their existence these shrines have not even bound all Hindus together. For, as the chief justice surely knows, for much of recorded history Hindu temples grievously discriminated against Dalits. The head priests of the most famous temples did not allow them to worship inside its premises. The Hindu religious tradition also discriminated against women, forbidding them from praying when menstruating. (Dalits and women were also discriminated against in many other ways – in terms of economic and political power for example.)

The chief justice says he is inspired both by Mahatma Gandhi on the one hand and by the tradition represented by the temples in places like Dwarka and Puri on the other. I would like to remind him that when, after Gandhi’s anti-untouchability campaign, some nationalists proposed a Temple Entry Bill in the colonial legislature, the Sankaracharya of Puri himself wrote to the viceroy that allowing Dalits and Savarnas to pray together “will really mean the sounding of the Death-knell of all possibilities for Sanatanists to lead quiet and peaceful lives of Spirituality according to the dictates of their Religion and their Conscience”.

Other influential Hindu priests organised a signature campaign to have Gandhi declared a “non-Hindu”.

Contrary to what the chief justice implies, there is a vast gap between the ideals of the orthodox Hindu tradition and the ideals that undergird our Constitution. Indeed, the Constitution is in good part a product of the tireless work of social reformers like Gandhi, Ambedkar, Savithri and Jotiba Phule, Gokhale, Ranade, and many others, to challenge forms of discrimination encoded in Hindu scripture, and practiced in everyday life.

Notably, even after the Constitution abolished Untouchability, the most famous temples in the Hindu tradition, such as Badrinath and Puri, continued to practice it for decades afterwards. As recently as July 2023, there were reports of several temples in Uttarakhand, Devbhoomi itself, denying entry to Dalits.

The treatment of women as inferior to men was also doggedly held on to by the Hindu orthodoxy well after 1950. A report from as late as 1988 mentions the Puri Sankaracharya as defending the practice of sati and as saying that women and Dalits had no right to read or interpret the Vedas.

It is true that no tradition is unchanging. However, it is quite likely that places like Puri and Dwarka would still have held on in toto to their anti-democratic and anti-egalitarian views had it not been for the Phules, Gandhi, Ambedkar, and the like, challenging caste discrimination on the ground – and had it not been for the Constituent Assembly of India, under Ambedkar’s direction, rejecting the Manu Smriti in favour of a democratic and egalitarian Constitution.

Therefore, for the chief justice of India to claim a congruence between the flag “that has traditionally flown above Hindu temples” and the modern text that is the Constitution of India is tendentious and misleading (to say the least). Let me remind him (and ourselves) of what the great historian of the Indian Constitution, Granville Austin said about it: namely, that the Constitution represented “a gigantic step for a people previously committed largely to irrational means of achieving otherworldly goals”.

I referred to the photograph accompanying the story in the Indian Express on the chief justice’s temple visits in Gujarat. This shows him dressed in a kurta coloured saffron. But even if his kurta was white or green, a serving chief justice making his temple visits so public at this particular juncture in our nation’s history, raise disturbing questions about his personal judgement. Meanwhile, the remarks he offered to justify them, where he claimed a continuity, an equivalence even, between Hindu tradition and the Indian Constitution, raise questions about his intellectual acumen.

(Ramachandra Guha is an Indian historian and writer. Courtesy: Scroll.in.)

Why CJI Chandrachud’s Statement on the ‘Saffron Dhwaja as a Unifying Symbol’ Raises Red Flags

Shamsul Islam

When D.Y. Chandrachud took charge as the Chief Justice of India (CJI) in November 2022, many from the so-called ‘liberal’ fraternity, who also claim to defend the democratic-secular polity of India, exhibited great happiness. They thought that, for some time at least, the idea of the Supreme Court being seen, if not actually conducting itself, as an appendage of the Narendra Modi-led government, had been deferred.

They underplayed the significance of him being on the bench that gave the notorious Ayodhya verdict on November 9, 2019. Many have called it out as an order grounded less in legal and constitutional points but more in an effort to placate a majoritarian agenda – one that is also advocated aggressively by both Modi and the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS).

On January 6, CJI Chandrachud endorsed saffron flags flying atop temples as “the flags of justice”.

After offering prayers at the temples of Dwarikadhish and Somnath with his family in Gujarat last week, the CJI had no qualms in saying, “I was inspired this morning by the dhwaja (flag) at Dwarikadhish ji, very similar to the dhwaja, which I saw at Jagannath Puri. But look at this universality of the tradition in our nation, which binds all of us together. This dhwaja has a special meaning for us. And that meaning which the dhwaja gives us is – there is some unifying force above all of us, as lawyers, as judges, as citizens. And that unifying force is our humanity, which is governed by the rule of law and by the Constitution of India.”

It is to be noted that all the above referred temples fly saffron/yellow flags atop their structures. This is bound to raise deep concerns if CJI Chandrachud, by these much publicised remarks, was implying that the tricolour or the Indian national flag was not the “unifying force” for Indians as were the flags that fly atop temples?

RSS accepted the tricolour only in 2002

The CJI’s statement has to be weighed against the context of the tricolour being chosen as the flag of free, independent and secular India. Unfortunately, the CJI was, knowingly or unknowingly, rephrasing the statement of the most prominent ideologue of RSS, M.S. Golwalkar.

Gowalkar, while addressing a Gurupurnima gathering in Nagpur on July 14, 1946, had said: “It was the saffron flag which in totality represented Bhartiya (Indian) culture. It was the embodiment of God. We firmly believe that in the end the whole nation will bow before this saffron flag.”

While denouncing the choice of the tricolour as the national flag, he said in an essay, titled ‘Drifting and Drifting’, in the book Bunch of Thoughts, “Our leaders have set up a new flag for our country. Why did they do so? It is just a case of drifting and imitating… Ours is an ancient and great nation with a glorious past. Then, had we no flag of our own? Had we no national emblem at all these thousands of years? Undoubtedly, we had. Then why this utter void, this utter vacuum in our minds?”

This seminal hatred for the tricolour even led the RSS to declare the tricolour as ‘evil’ on the eve of independence. The RSS’s English language mouthpiece, Organiser, demeaning the choice of the national flag, wrote: “The people who have come to power by the kick of fate may give in our hands the tricolour but it never be respected and owned by Hindus. The word three is in itself an evil, and a flag having three colours will certainly produce a very bad psychological effect and is injurious to a country.”

The RSS borrowed this hatred for the tricolour from V.D. Savarkar who declared that “The Charkha-Flag (then the tricolour used to have a charkha or a spinning wheel in the middle, which was later replaced by the Ashok Chakra), in particular, may very well represent a Khadi-Bhandar, but the charkha can never symbolise and represent the spirit of the proud and ancient nation like the Hindus.”

It is a cause for concern that the CJI, who is duty-bound to safeguard the democratic-secular polity of India, which the tricolour so evocatively embodies, appeared to be chiming more with those who protested the tricolour for decades before accepting it grudgingly.

(Shamsul Islam is a retired professor of Delhi University, an activist, author, and theatre person based in Delhi. Courtesy: The Wire.)

Must Justice Have a Colour?

Manash Firaq Bhattacharjee

In an “inspired” statement after visiting the temples at Dwarka and Somnath in Gujarat earlier this January, Chief Justice of India D.Y. Chandrachud said:

“I was inspired this morning by the dhwaja at Dwarkadhish ji, very similar to the dhwaja, which I saw at Jagannath Puri. But look at this universality of the tradition in our nation, which binds all of us together. This dhwaja has a special meaning for us. And that meaning which the dhwaja gives us is– there is some unifying force above all of us, as lawyers, as judges, as citizens. And that unifying force is our humanity, which is governed by the rule of law and by the Constitution of India.”

It is a dense statement with philosophical implications if connected to the future spirit of the law in India. There is a politics of mysticism behind the statement. The statement suggests that behind (and “above”) the force of law is another “unifying force”. This force binds us prior to the force that binds us to the law. It is the force of national tradition.

The dhwaja, or flag, in a temple represents the idea of a specific tradition within a nation. It does not represent all other traditions. The flag or any other symbol belonging to a tradition can’t be universal. To consider tradition as part of sacred territory is still an argument of difference, distinguishing it from other traditions. It is not a mark of universality.

Universality is an idea connected to a secular culture (and a secular state). It does not represent any tradition. The principle of universality in a nation comes from the life that people of various cultures and traditions share together as citizens. Nehru called it “a sense of common living and common purpose” in The Discovery of India. The “special meaning” of traditions doesn’t become less special if it isn’t universal. Traditions are special precisely because they add to a nation’s diversity. To consider the “unifying force” of tradition “above” all of us suggests that we are bound to a tradition before we are bound to any other idea or system of law. But the force of tradition can’t undermine the law of the state if that relationship has to be retained in any meaningful manner.

Traditions are prejudicial, and their pretention to universality is circumscribed by prejudice. The profound prejudice of traditions governs the lives of people who swear by it. It also governs people’s lives with others, those who do not belong to that tradition. The relation between traditions is governed by mutual prejudice. There are, however, ethical guidelines within traditions regarding how to relate to others outside it. These guidelines are part of the law of tradition, the tradition of law that predates the universal law of the secular state. These guidelines are still not universal, for each tradition understands its relation with others in distinct ways, connected to its own precepts and history. The ethical nature of the relationship between traditions is derived from their mutual capacity to partake in shared life. The element of prejudice however persists in that relationship, and is often the cause of mutual animosity and strife. Justice in a secular nation is often, simply, the management of strife.

In Pensées (1670), Pascal identifies three sources behind the essence of justice: legislative authority, sovereign interest, and the surest of all, current custom. Justice is not eternal, but a matter of time. In his famous essay “On Experience” (1587-1588) Michel de Montaigne calls custom the “mystical foundation of authority”, where he means to say that people follow the law not because it is just (or, brings justice) but because they are laws to be obeyed. One obeys, or bound to obey, authority, even if it isn’t just. Authority is a matter of collective belief, ruled by custom. Montaigne suggests that the customary nature of law prevents the possibility of imagining the just. It curtains, curtails justice. Does secular law overcome the constraints of custom to become, or realise itself as, universal, and just? Can this law become what Aniket Jaaware meant in his evocative phrase in Practising Caste: On Touching and Not Touching by “just us”? In his words: “Not us and them, not you and me making up a divisible us. Just us.” Justice is us, about us, the un/just us, the destitute of law. It is an undefinable us that cross the crisscrossed borders of traditions to seek what makes us, and what is denied us.

Let us go back to the Chief Justice’s statement. He not only invokes tradition but also “nation”, equating the two to mean that there is a tradition of the nation that is symbolised and embellished by the dhwaja on the temple. The force of tradition binds both the giver and receiver of law, which in turn forms the essence of the rule of law and the Constitution. The question arises: Does this force of tradition include the force of other traditions? In other words, can “universality” be posed as an idea (and a value) within– in the name of– the nation by not naming the diversity of traditions within it? Can the idea, or essence, of a singular custom become the unitary basis of the law, of that elusive possibility we call justice? Are “lawyers”, “judges” and “citizens” together bound by a single tradition as the “unifying” source of our prejudicial authority? What if the idea of unity– proposed in the name of a “unifying force”– does violence to the idea of diversity?

It is also not that traditions are eternal, immune to changes. They have evolved across time and undergone numerous improvisations through internal debates. Traditions are always in flux. The element of prejudice in traditions includes caste and gender. Nehru underlines modernity’s critical relationship with tradition succinctly in The Discovery: “Traditions have to be accepted to a large extent and adapted and transformed to meet new conditions and ways of thought, and at the same time new traditions have to be built up.” Traditions are not sacrosanct.

A flag belonging to a tradition also has a colour to it. Traditions, among other things, are also a display (and play) of colours. The colour of tradition is a singular colour within a diversity of colours. Can it also colour the law? Are the laws of the world (especially that of secular states) coloured by the mystical force of authority? The blind/ed figure of the law gives the impression that the law is also colourblind. Justice, we understand, has no colour. Is it just a foundational myth of the law’s representation of itself?

To end, I shall invoke a line from Jacques Derrida’s essay “Force of Law: The Mystical Foundation of Authority” (1994), the force behind my meditation: “To address oneself to the other in the language of the other is both the condition of all possible justice.” The ethical condition of modern (secular) law presupposes disputes between people following different customs and traditions, therefore different prejudicial authorities. In a similar manner, the law of the nation presupposes a society of minorities. The idea of unity, in this sense, presupposes the existence of diversity. It makes the law bound to the history (and possibility) of many customs, or traditions, that resource the “unifying force” behind the idea, and spirit, of justice. The force of law of my tradition is paradoxically limited and expanded by the presence of the force of law of the other who belongs to another tradition. It is the other that brings the fundamental predicament to law and justice: How to be just to what is prior to – and yet becomes the basis of– unity?

The law must arbiter between our mutual prejudices. It must be above what limits us.

(The writer is the author of ‘Nehru and the Spirit of India’. Courtesy: The Wire.)