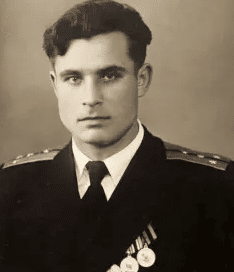

On October 27, 1962, Soviet naval officer Vasily Arkhipov helped prevent the outbreak of World War III and saved humanity from nuclear catastrophe.

A minesweeper during the Pacific War, Arkhipov was the commander of a diesel submarine that had been sent by Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev to escort merchant ships bound for Cuba, which were equipped with a torpedo boat armed with a nuclear warhead.

On October 14, 1962, a U.S. spy plane flying over Cuba had revealed that the Soviet Union was building ramps for the installation of missiles with nuclear warheads, in retaliation for the United States deploying missiles with nuclear warheads capable of striking the Soviet Union in Italy, at Gioia del Colle (Apulia in southern Italy), and in Turkey.

President Kennedy’s imposition of a naval blockade after the spy plane discovery triggered the 13-day Cuban Missile Crisis, during which time the submarine that Arkhipov commanded was being pursued by U.S. destroyers which, using depth charges, were trying to force Arkhipov’s submarine to the surface.

After the Soviet sub’s ventilation system broke down and communication was cut, the captain of the Soviet submarine group, Valentin Grigoryevich Savitsky, was convinced that war had broken out.

Not wanting to sink without a fight, he decided to launch a nuclear warhead at the aircraft carrier pursuing his sub.

The political officer, Ivan Semyonovich Maslennikov, agreed with the captain, but on the flagship B-59, Arkhipov’s consent was also needed, and he objected, convincing Savitsky ultimately to do the same.1

Arkhipov’s persuasion averted a nuclear war, whose consequences would have been horrific. After surfacing, Arkhipov’s sub was fired on by Americans but was able to return to the Soviet Union safely.

Spooked about how the world had come so close to the nuclear brink, President Kennedy gave a speech at American University in June 1963, five months before his assassination, calling for a “reexamin[ation of the U.S.] attitude towards the Soviet Union” and “Cold War” and for the U.S. and Soviets to work together for a “just and genuine peace” and to “halt the arms race.”

“Confident and unafraid,” Kennedy concluded, “we must labor on—not towards a strategy of annihilation but towards a strategy of peace.”

Another Grave Moment of Danger

Defense Secretary Robert S. McNamara was not mincing his words when he said years after the events that “We came very, very close [to nuclear war during the Cuban missile crisis,] closer than we knew at the time.”

Arthur Schlesinger, Jr., characterized the period of the Cuban Missile Crisis as “not only the most dangerous moment of the Cold War [but] the most dangerous moment in human history.”

That moment of danger unfortunately appears just as sharp today.

Time magazine reported in late October that Russia’s launching of missile strikes targeting energy plants within Ukraine and civilian infrastructure “triggered fears that hostilities were escalating and inching closer to nuclear war.”

The U.S. had stoked the fire by a) engaging in provocative military drills testing the handling of thermonuclear bombs; b) delivering bombers to Europe equipped with low-yield tactical nuclear weapons; and c) carrying out acts of international terrorism such as the sinking of the flagship vessel of the Russian Black Sea Fleet called the Moskva that prompted Russian President Vladimir Putin to place Russia on high nuclear alert.

The U.S. was generally the one to provoke a new Cold War with Russia by a) expanding NATO towards Russia’s border; b) imposing economic sanctions on it under fraudulent pretexts; c) and then backing a coup in Ukraine that triggered the conflict in eastern Ukraine which has evolved into a proxy war.2

In October 2018, the Trump administration pulled the U.S. out of the 1987 Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces (INF) agreement, characterized by former U.S. ambassador to Russia Jon Huntsman, Jr., as “probably the most successful treaty in the history of arms control.”3

Carl J. Richard, head of the U.S. Strategic Command (STRATCOM) which oversees the nation’s nuclear arsenal, wrote in the U.S. Naval Institute’s monthly magazine subsequently that the U.S. military had to “shift its principal assumption from ‘nuclear employment is not possible’ to ‘nuclear employment is a very real possibility,’” in the face of threats from Russia and China.

Richard’s successor, Anthony J. Cotton, said just as ominously during his confirmation hearing in September that his job was to prepare the 150,000 men and women under his command to deploy nuclear weapons, and that the president should have flexible nuclear options.

Both Richard and Cotton appear to be of the opposite character of Arkhipov, whose level-headedness under pressure and commitment to peace between the U.S. and Russia needs to be remembered at this time.

In a deeply Russophobic climate, Arkhipov should remind us also not to associate Russians with the stereotyped qualities promoted about them in Hollywood films—and in the ravings of Pentagon war planners and politicians who have led us into another grave crisis.

Notes:

- See Ron Ridenour, The Russian Peace Threat: Pentagon on Alert (New York: Punto Press, 2018), chapter 5.

- See Jeremy Kuzmarov and John Marciano, The Russians are Coming, Again: The First Cold War as Tragedy, the Second as Farce (New York: Monthly Review Press, 2018).

- See Scott Ritter, Disarmament in the Time of Perestroika: Arms Control and the End of the Soviet Union (Atlanta: Clarity Press, 2022) on the lost promise of the disarmament treaties of the late Cold War era.

[Jeremy Kuzmarov is Managing Editor of CovertAction Magazine and author of The Russians Are Coming, Again, with John Marciano (Monthly Review Press, 2018). Courtesy: CovertAction Magazine, a project of Covert Action Publications, Inc., a not-for-profit organization incorporated in the State of New York.]