The present moment in our contemporary history is riddled with paradoxes. The year, 2021, marks the commencement of our existence as an independent country for over seven decades. It naturally reminds citizens of India’s epic struggle for freedom, bringing to us the haloed memory of martyrs who laid down their lives dreaming of the freedom to come. It makes us want to revisit the lives and thoughts of the towering leaders who spread the idea of freedom in a country that had gone into a deep slumber and made it aspire to be free.

But 2021 is also the year when the prime minister’s Independence Day speech from the Red Fort was delivered without mentioning Mahatma Gandhi even once. The year should remind every Indian that exactly one hundred years ago, Barrister Gandhi took charge of the Congress and became its president at the party’s session in 1921. His leadership gave the Congress an ideological vigour that would rattle the colonial government. Yet, 2021 is also the year when we see the Congress drifting apart week by week without even murmuring to itself what its ideology is.

This is the year marking the launch of B.R Ambedkar’s Mooknayak, a journal that provided the foundation for subsequent social rights movements in India through the last one hundred years. It is also, paradoxically, the year when Dalits are being lynched by mobs more frequently than ever before.

This is also the time to remember that a century ago, the Afghan War had shown that the Asian people could successfully combat the might of the British military, binding the Afghans and the Indians in a close emotional bond. In contrast, 2021 marks the year of the Taliban takeover of Afghanistan, a development that has given the Islam-baiters in India a convenient handle to indiscriminately demonize all Muslims of the subcontinent.

Fifty years ago, in 1971, India had rushed to help Bangladesh gain its nationhood. In 2021, assembly elections in Bengal were fought as if the leaders of the Central government and those of the Bengal government belong to two different planets.

Paradoxes abound. However, the most disturbing of all these for me is that 2021 marks the 150th year of the enactment of the first Criminal Tribes Act in 1871. In the 75th year of India’s Independence, even after a century and half, those who remain the hapless victims of the CTA still cannot see a ray of hope. Let me recount, in brief, the sordid tale.

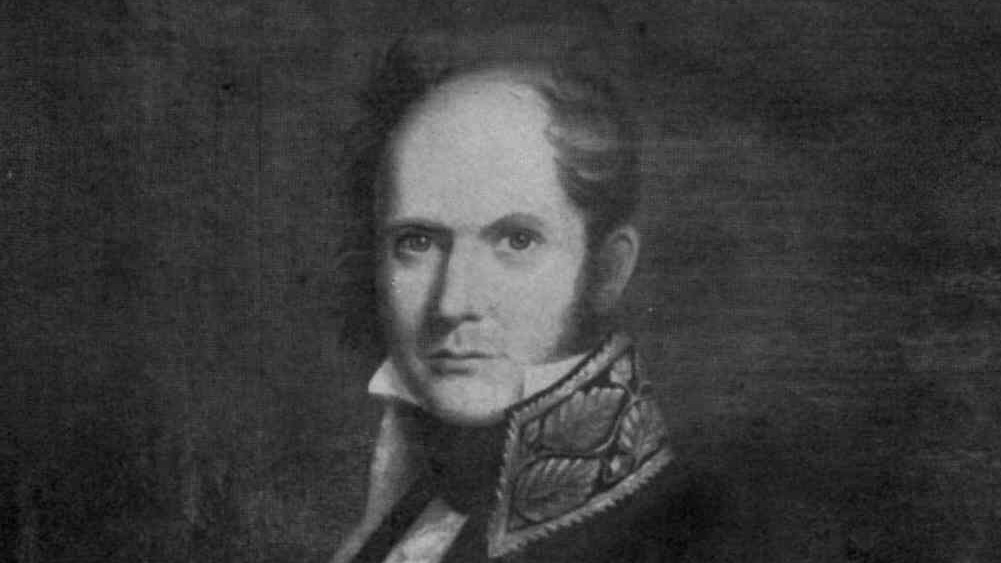

Ordinarily, contemporary Indians do not have a good reason to remember General William Henry Sleeman (1788-1856), a British officer who spent his life from the age of 21 working in the colonial administration for over four decades. That he chanced upon the fossils of the extinct Narmada basin dinosaur interests none outside the small circle of archaeologists. However, he was the one who created an abiding fiction related to a certain class of Indians. During the 1830s, he was appointed the ‘Commissioner for the Suppression of Thugee and Dacoity’. The grand name given to the office suited the colonial narrative perfectly since British authority rested on the idea of creating the rule of law and order. Sleeman took to the task with furious passion. Not only did he list every possible case of clashes and crime taking place in central India but also put them through hurried trials, leading to the hanging of 1,400 individuals during his tenure. One does not know if all or any of them received the benefit of legal aid from the colonial government. Those were still the days of the Company sarkar, and such an expectation would have been unrealistic. The result of the Sleeman mission was the creation and the circulation of numerous stories related to thugs and their criminal mindset; how much of the fact is fiction has not yet been ascertained.

The idea that certain communities, not just some of their members, are given to criminal activity as their regular livelihood took root in the minds of the rulers. One of the undeclared intentions of Sleeman’s mission was to disarm the wandering soldiers of the defeated princes in India; therefore, most of the communities under Sleeman’s scanner were nomadic communities. The intent and the myth came together in the letter and spirit of the CTA of 1871. The Act held entire communities to be criminal in inclination. The remedy for the perceived criminality suggested by the CTA was to prevent the communities from continuing their nomadic life. Hence, the communities covered by the CTA included primarily nomadic and pastoral ones. They were kept confined in reformatory settlements — jails of a kind. With this, they became stigmatized forever, irrespective of whether an individual member in such communities had committed any crime. The CTA was revised several times during the colonial regime, its scope expanded each time to include more and more communities. Thousands died in these settlements. They were put to hard and unpaid labour. Several generations passed and the stigma became thicker.

India had all but forgotten about them when Independence arrived. These communities continued to rot inside the settlements. It was in 1952 that, thanks to the report of the Iyengar Committee, the CTA was withdrawn and was replaced by the Habitual Offenders Act, aimed at individuals rather than communities. Since the earlier notifications were withdrawn, these communities came to be known as the Denotified Tribes, most of whom were nomadic by habit. The pastoral and semi-nomadic communities came to be abbreviated as SNTs. If a careful count were to be made in all Indian states, these communities would number over 250. And what may be their population? Based on the 1931 census, the estimates made varied between 8-15 crore, although their exact number was not known. Since the process of preparing the lists of the SCs and the STs had begun before the denotification process of the DNTs and SNTs began, many of these communities remained outside the benevolent framework of affirmative action. They were left without land, livelihood and government patronage, hounded out from villages and mob-lynched frequently in cities. Thousands of them are forced into a life of crime by the system that requires scapegoats to cover the big fish in the world of crime. Many are rotting in jails for life; many die in custody without a mention in the media.

Over the last several decades, they have been asking for a proper census since getting counted could be the first step towards receiving State benefits. Yet, that has not happened. Will India turn a deaf ear to their pitiful cries during the 2021 census is anybody’s guess in this year of paradoxes.

(G.N. Devy is a literary critic and cultural activist. He is founder, Denotified and Nomadic Tribes Rights Action Group. Article courtesy: The Telegraph.)