It is beyond my understanding, commented Bihar chief minister Nitish Kumar, how history can be changed. He was responding to the instructions given by the Union home minister – that perceived imbalances in India’s written history should be rectified.

“History is what it is. History is history,” stated Kumar, when he was asked to respond to Amit Shah’s suggestion that historians have given more importance to the Mughals at the cost of underplaying empires like the Pandyas, Cholas, and the Ahoms. “Writing and language,” he said “is a different issue, but you can’t change history.”

Beyond the two comments made by politicians – no doubt for their own purposes – lies a contentious debate on historiography, on epistemology, on theory, and on the art of writing. It is true that we cannot change history. If Dilip Kumar played Devdas in Bimal Roy’s famous film, well then, Dilip Kumar played Devdas. There can be no argument on this, no one can say that the ‘king of tears’, Rajendra Kumar, played Devdas in Roy’s movie, though he did play a weeping spurned lover in many other films.

Yet film critics can disagree on the merits of the film: whether Dilip Kumar played the role well, or indifferently, or competently, or casually. They can agree or disagree whether Bimal Roy was faithful to the novel by Saratchandra Chattopadhyay. And they can read into the film the social context of the times.

I recollect teaching my students that Devdas was a metaphor for a decaying feudal order that had been constructed by the British in Bengal through the Permanent Settlement. The falling apart of a man, who drew upon the family estate to drown himself in wine, women, and song, was an allegory for a crumbling feudal class which lived off rentals and had forgotten how to work for a living.

The theme of a degenerating feudal class was reiterated in one of Guru Dutt’s best films, Sahib Bibi Aur Ghulam.

The other side of the Permanent Settlement was, of course, Bimal Roy’s Do Bigha Zamin with the central character played marvellously by Balraj Sahni.

Of course my students were much more conversant with Bhansali’s depiction of Devdas overplayed by Shahrukh Khan amidst unnecessary, opulent settings. But that is not the point I wish to make. The point is that a historical event happened, and historians will interpret this event in different ways.

Reams, for example, have been written on the 1857 revolt. A historian who is faithful to her craft will hardly disagree that the mover of the revolt was the feudal nobility whose privileges were appropriated by the colonial government. At some point she has to accept this aspect of history. Taking that as her anchor, our historian can interpret the revolt in her own way providing she is faithful to the staples of the historian’s craft – meticulous attention to detail, acknowledgement of other work on the same theme, sound theoretical understanding, and appreciation of the context.

Every book that is written on the past by an aspiring historian is not history. History is a specialised discipline that wends a careful and delicate way through the maze of what happened, and how we justify our interpretation of what happened.

The problem is not that we reconstruct an event that happened in the past. The problem is that we can never resurrect the past simply because we approach the past from our vantage point in the present. There can be no objective recounting of the past. In that way history is a ‘presentist’ discipline. When we reconstruct the past through the mode of a narrative we are condemned to selectivity.

Take the British historian George Grote (1794-1871), whose notion of constitutional morality Dr B.R. Ambedkar introduced members of the Constituent Assembly to. Grote had authored 12 volumes on the history of Greece (1846-1856).

Intent on defending Athenian democracy against its critics, Grote suggested that Athens had given to the world a notion of democracy that rested on the twin planks of freedom and self-restraint, generating what he called constitutional morality.

Grote’s critics allege that his ‘apologia’ for Athens was not about Athenians but about his own generation. It was about Victorians who respected character born out of thrift, industry and prudishness.

In his famous lectures on What is History, E.H. Carr wrote that Grote, an enlightened radical banker writing in the 1840s, embodied the aspirations of the rising and politically progressive British middle class in an idealised picture of Athenian democracy.

In Grotes’s story of Athens, Pericles figured as a Benthamite reformer, and Athens acquired an empire in a fit of absence of mind.

“It may not be fanciful to suggest that Grote’s neglect of the problem of slavery in Athens reflected the failure of the group to which he belonged to face the problem of the new English factory working class,” says Carr.

The criticism is well taken. How can a historian depict Athens without recording that ancient Greek civilisation was based on slavery? The narrative, we see, imposes order on a society marked by hierarchies and exclusions.

This is precisely the problem with Hindutva versions of history that posit the idea of a “civilizational state” as the foundation of India’s democratic structure, and which downgrade the constitution as the founding moment of our democratic community. Their objective is painfully evident: justification of majoritarianism without subtlety, without nuances, and shorn of historical detail. The ancient past of a Vedic Hindu India is connected to the present in a seamless manner, as if transformations in the political economy of society, or indeed the massive migrations in history do not merit a comment even in passing.

The poet Firaq Gorakhpuri had famously written:

“Sar Zamine-e-Hind par aqwame-e-alam ke Firaq/

Kafile baste gaye/ Hindostan banta gaya”.

India was created as a plural society, wrote the poet, by successive waves of migration. People came in caravans and settled here. In 1947, a society that had been fashioned by a groundswell of travellers deciding to settle in its territory, witnessed processions of bedraggled, dispossessed people travelling from the East to the West, and from Western to Eastern Punjab. How was civilisation not impacted by this rupture in our collective life?

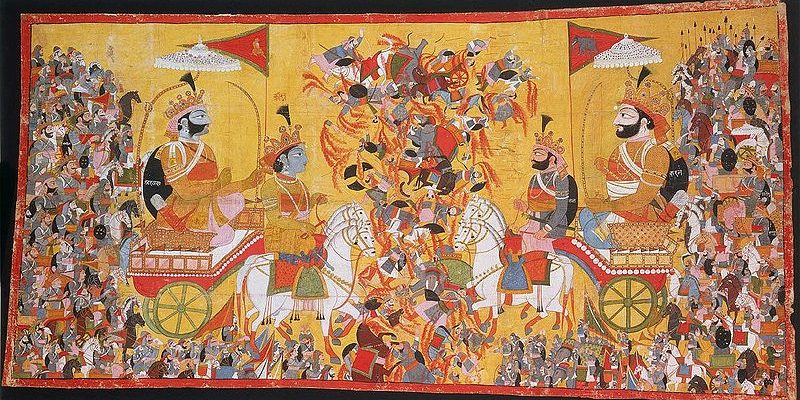

The purveyors of the Hindutva point of view invoke a Hindu past – hierarchical, Brahmanical, metaphysical and abstract. They marginalise or demonise the Mughal period, and deliberately ignore the fact that unlike earlier invaders, Mughals settled in India and contributed to the making of a creative culture.

Professor Gopi Chand Narang, who died earlier this week, suggests in his 2020 work, The Urdu Ghazal: The Gift of India’s Composite Culture, that the fount of Sufism was the Hindu tradition, not found anywhere else.

Hindus and Muslims celebrated festivals, from Holi, Diwali and Basant to Muharram and Shab-e-Baraat together. The emperors Humayun and Akbar gave up their traditional head gear in favour of the Rajasthani turban. Singing of qawwalis at the dargahs of Muslim peers brought a new element into Islam and broke the taboo on music before the mosque. The guru-shishya parampara, meditation, zikr or the remembrance of God, tauba or repentance, unconditional self-abnegation, and love for the guru generated a form of fusion that enriched both cultures.

Hindus continue to worship at the graves of Sufi saints till today.

Musical instruments like sitar, sarod, table, and sarangi, an invention of Muslim musicians, became a part of the tradition of Indian music. Bhajan kirtan that resulted in the popularity of khayal-gayiki was invented by Muslim musicians. And the Hindu musical tradition of dhrupad along with khayal became part of the same tradition. The Mughal court was a major patron of art, music and musicians – remember Tansen in Akbar’s palace in Fatehpur Sikri.

“In this and many other fields of art, poetry, and painting the fusion is so complete and the flowering is so thorough and so creative that a whole new rainbow-like artistic range came into being, which is now a permanent part of the cultural tradition,” writes Narang. This exists till today despite the manufacture of religious differences.

On the other hand, the epistemological dominance of British colonialism was not so much a fusion as a one-way traffic. The philosopher Kalidas Bhattacharya in his editorial note to Recent Indian Philosophy, a collection of a number of papers from the proceedings of the first decade of the Indian Philosophical Congress (1925-1934), writes:

“It is unfortunate that though the thinkers whose papers are published in this volume are all Indian and though for that reason we ought to have called their thinking Indian Philosophy we cannot do that…because…the living continuity of their philosophical thinking with the old philosophical traditions was snapped…and it has not been completely restored even today.”

Indian philosophers took on board and absorbed the European philosophical tradition. They also reinterpreted indigenous concepts in light of what was absorbed. Consequently, we simply do not know what our past was independently of colonial structures of interpretation. The German Romantics interpreted a glorious Indian past and consequent decline. This was accepted uncritically by most nationalist thinkers, and till today the medieval period is completely eliminated from all stories of our great civilisation. This was the impact of the Western understanding of India – an understanding which continues to fascinate our current ruling class.

But British colonialism also gave to us new fields of literature and poetry, from Socrates to Shakespeare, from Houseman to T.S Eliot. How closed, how claustrophobic the Indian mind would have been without exposure to Ghalib and to Byron, to Shakespeare and to Hollywood movies, to Bach and to Urdu poetry. Why should I as an Indian not draw my identity from Firaq Gorakhpuri and Shakespeare, from Plato and Rawls, from Buddhism, from the equality of the Islamic faith, from Mother Teresa, and from Sahir Ludhianvi as much as from the Bhagvadgita and the caves of Ajanta and Ellora?

All these strands constitute our civilisation. They have expanded our minds, and they have widened our horizons. These cultures are as much a part of our civilisation as the epics. This is what the great Indian civilisation is about – a number of tributaries flowing into the same river, the mighty Ganges.

The invocation of history is important because we must know where we came from. At the same time, we must learn from history and not repeat its mistakes ad infinitum. A number of Indians who subscribe to Hindutva argued proudly that they are trying to date the Mahabharata. We do not know whether anybody will benefit from dating the great war. We only recollect the lessons of the fratricidal conflict.

The poet Amreeta Syam scripts an imaginary conversation between Subhadra, married to the hero of the epic, Arjun, and Lord Krishna in the poem ‘Kurukshetra’. The Great War of the Mahabharata has generally been understood as a war of the just against the unjust, a war of the righteous against the unrighteous. The human costs of the war were nevertheless beyond compare. It is precisely these costs that Subhadhra asks the God to account for. In despair, because her young son Abhimanyu was brutally killed in the Great War, she introduces a subversive note into the dialogue:

“This is a fight for a kingdom/ Of what use is a crown/ all your heirs are dead/ When all the young men have gone/ …And who will rule this kingdom/ So dearly won with blood/ A handful of old men/ A cluster of torn hopes and thrown away dreams.”

So true. When goons kill young men who were going to inherit India, who will replace them? A handful of grey beards?

There is a second lesson we learn from the Mahabharata.

In section LIX of the Santi Parva, Yudhistira asks Bhishma about the origins of kingship and of the symbol of power the danda, or the sceptre. The gods, says Bhishma to Yudhistira in his discourse on righteous rule, created the institution of kingship for one main objective: the protection of the people. ‘If there were no king on earth for wielding the rod of chastisement, the strong would then have preyed on the weak after the manner of fishes in the water.’ The king has to protect all creatures, even if he is personally inclined to dislike them. He protects them from external impediments such as threats of violence, but he also provides the preconditions of material flourishing. ‘As the mother, disregarding those objects that are most cherished by her, seeks the good of her child alone, even so, without doubt, should kings conduct themselves (towards their subjects). The king that is righteous…should always behave in such a manner as to avoid what is dear to him, for the sake of doing that which would benefit his people.’

The king who follows the path of dharma is the creator; a sinful king is the destroyer. The ruler should beware of exploiting the weak, for the eyes of the latter can scorch the earth. ‘In a race scorched by the eyes of the weak, no children take birth. Such eyes burn the race to its very roots…Weakness is more powerful than even the greatest Power, for that Power which is scorched by Weakness becomes totally exterminated. If a person, who has been humiliated or struck, fails, while shrieking for assistance, to obtain a protector, divine chastisement overtakes the king and brings about his destruction.’

The divine rod of chastisement falls upon the king. If it practices injustice, a great destruction comes upon the state. This is Raj Dharma, the dharma that our ruling class claims to rule by. It has, however, failed to implement Raj Dharma. We bear witness to the terrible way in which minorities are being harassed. The justification of Hindutva has not withstood the test of time.

The narrative of Hindutva seeks to exclude an entire period which contributed to the making of our civilization from cuisine to miniature painting to architecture. History is time and time unlike space is plural. A number of things happen at a point in time. That is why historians craft narratives to recount history.

Narratives are, however, exclusionary – they leave out much more than they include. The literary form imposes order on the chaos that marks every moment in history. If we have to impose a narrative to make sense of history, why not choose to learn from history instead of using it to legitimise injustice and attacks on our plural culture?

Finally, though narrative is a perfectly legitimate form of history writing, a handful of loose assertions do not make for either a coherent or a persuasive story. Those putting forth an ill thought idea of a Hindu civilisational state betray their own inadequacies, ignorance and lack of responsibility. A responsible historian does not widen the schisms of a society, she builds bridges to show commonalities and solidarities.

Unless these conventions are followed scrupulously, we will only have court histories, not histories that capture the overlaps as well as the contradictions of history.

(Neera Chandhoke was a professor of political science at Delhi University. Courtesy: The Wire.)