Ajai Shukla

Details of the mutual troop disengagement in the contested Galwan River valley, which senior government sources have shared with Business Standard, illustrate that the Line of Actual Control (LAC) — the de facto border — has been effectively shifted by a kilometre into India.

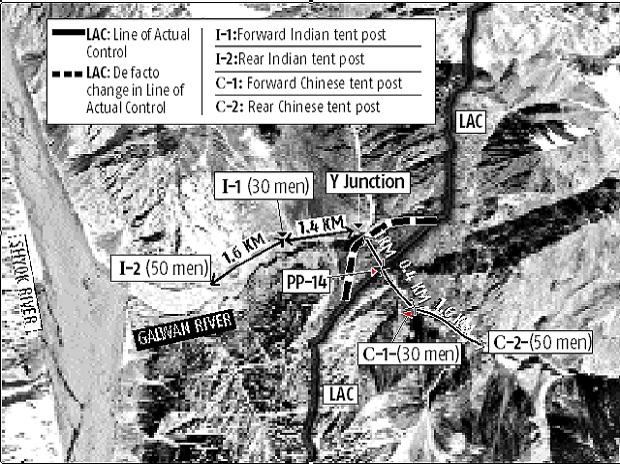

The terms of disengagement, negotiated on June 30, regard the LAC as running through the so-called Y-Nallah Junction. This is 1 km inside India, when compared with the LAC’s historical alignment next to Patrolling Point 14 (PP-14). The area in which PP-14 is located – and which the Indian Army has patrolled for decades – now effectively falls inside China’s “buffer zone”.

The disengagement plan, drawn up by India’s Leh Corps commander Lieutenant General Harinder Singh, and China’s South Xinjiang Military Region commander Major General Liu Lin provides for a buffer zone of 3 km on both the Indian and Chinese sides of the LAC. The plan permits each country to maintain two “tent posts” in its buffer zone. The forward tent post will be located 1.4 km from the Y-Junction. Their second tent post will be 1.6 km further behind the forward post, i.e. 3 km from the Y-Junction.

Each country is permitted to maintain 30 soldiers in its forward tent post and another 50 in its rear tent post. A tent post, as its name suggests, is an encampment that has only temporary structures. Permanent structures would allow India to stake a claim over the Galwan valley.

By restricting the Indian presence to tent camps, China can continue with its new claim over the entire Galwan River valley – which it has voiced several times in the past two months.

Army sources point out that by measuring all distances from the Y-Junction, rather than from the traditional LAC alignment west of PP-14, the Y-Junction has been effectively regarded as the LAC point.

It is learnt that this was done on the insistence of Chinese military negotiators. New Delhi continues to insist that the LAC runs along the line of PP-14, but has undermined its own claim by agreeing to locate its forward tent post 2.4 km from what it claims is the LAC, while allowing the Chinese forward tent post to be just 400 metres from our claimed LAC.

For now, neither country is permitted to send patrols ahead of their forward tent post. That means the Indian army, which earlier sent patrols all the way up the Galwan River valley to PP-14, will have to maintain a distance of 2.4 km from PP-14. In contrast, Chinese patrols can come up to 400 metres from PP-14.

Meanwhile, no agreement has been reached for the Chinese to disengage or pull back from confrontation points south of Galwan at PP-15 and Hot Spring area, where large numbers of Indian and Chinese soldiers continue their face-off.

Near PP-15, where the Chinese have built a road extending 3 km into Indian-claimed territory, more than 1,000 Chinese troops are eyeball-to-eyeball with an equal number of Indian soldiers.

In the Hot Spring area, the Chinese have not built a road, but over 1,500 Chinese troops have intruded 2-3 km into Indian territory at the Gogra Heights (PP-17A) and are being blocked by a matching Indian deployment.

Nor is there any agreement on disengagement in the Pangong Tso sector. Here, Chinese troops have crossed the existing LAC that ran along a mountain spur called Finger 8 and intruded 8 km into Indian-claimed territory up to a spur called Finger 4. Indian troops have traditionally patrolled up to Finger 8, but are now being blocked by the Chinese intruders at Finger 4. It is understood the Chinese are refusing to withdraw to Finger 8 unless India withdraws to Finger 2.

Indian Army planners find themselves contemplating the possibility of more Chinese intrusions along the contested 3,488-km border. That could lead to the army having to man a “hardened LAC” round the year, like the Line of Control (LoC) with Pakistan.

Besides the heavy cost of setting up this border infrastructure, the Indian army, which already spends three quarters of its budget on salaries and pensions, could find itself requiring even more manpower.

Army planners also worry that a heated LAC, with an additional commitment of troops and equipment, would erode India’s conventional first-strike deterrent against Pakistan.

(Ajai Shukla, a retired Indian Army colonel, is a consulting editor for the Business Standard newspaper in New Delhi.)