What happened to Professor Tejaswini Desai of Kolhapur can happen to anyone in the teaching community. It tells you of the perils of being a teacher in India of our times. Teachers can no longer assume that the class is over after the stipulated period of 55 or 60 minutes. Whatever transpired in the class can continue to be played out on social media for days on end, often without the teacher even being aware of it. The teacher can then be held accountable by those who have never been part of their class, people they have never known, and whose opinions they will now have to face.

Tejaswini Desai, an Associate Professor of Physics at Kolhapur Institute of Technology’s College of Engineering in Maharashtra, has been put on leave pending the completion of an inquiry against her.

What wrong did she commit?

Professor Desai was conducting a class on human values. This was not her regular class; she was taking over after the previous lecturer’s resignation. The students informed her that the class had been discussing the idea of discrimination and they wanted to continue with it. She agreed and proposed a discussion on gender discrimination. However, the students insisted on discussing religious discrimination instead, to which she agreed.

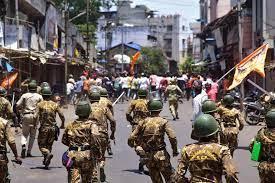

Professor Desai was aware of the context. Kolhapur was still recovering from episodes of communal violence that broke out after someone made Aurangzeb’s image the status of their social media account. Considering this, one might say it was courageous of Professor Desai to agree to discuss the topic. Like all teachers, she must have felt that there should be no hesitation in discussing things with students if they want to learn about them.

During the discussion, some students began reiterating prejudices and false claims against Muslims that are prevalent in Hindu society today. They claimed that all Muslims are rapists, violent, and obstruct Hindu festivals. Furthermore, they asserted that the Babri Masjid had been demolished on the orders of the Supreme Court.

Professor Desai was shocked to hear these opinions. She responded by stating that rape is a crime that can be committed by men of any religion, including men from the Deshmukh or Patil communities (dominant caste groups in Maharashtra).

Unknown to Professor Desai, some students were recording the classroom discussion. Nearly a week after the class, she was called to the principal’s office where a police officer was also present. She was informed that an edited video of the discussion had been circulating on various social media platforms. The video alleged that she had referred to Aurangzeb as a good man while calling Patils and Deshmukhs rapists. Professor Desai was shocked to see that her comments had been completely distorted.

The police claimed that they had seen the social media exchanges and had come to the college to question her. It is surprising to see such swift action by the police! The college administration asked Professor Desai to resolve the matter by apologising, but she stood her ground and refused. As a result, a committee was formed to investigate the matter, and she has been asked to go on leave until then.

We can admire Professor Desai for her courage, but teachers should not need such extraordinary courage to fulfil their normal duty, which is teaching. This is exactly what Professor Desai was doing: performing her duty as a teacher. She was doing what all teachers are supposed to do. As Professor Desai has stated, she had to make her students reflect on their ideas, to critically examine themselves, and to question the ideas or opinions held dear by their families.

It is an unsettling process for the students. But this is what teachers are supposed to do: challenge and provoke students to think independently. Moreover, students need to be taught that everything they do should be infused with empathy for others. And if this is not instilled in a class that teaches human values, then where else?

By questioning her students’ prejudices against Muslims, Professor Desai was actually helping them dispel the basic factual untruth that there are no rapists or criminals among communities other than Muslims. How is it possible that university students did not know that rapists can be found in all communities, including their own? What have they been reading? Who have they been listening to? How have they been indoctrinated with such false notions?

To witness students using radicalised language and remaining silent just to maintain peace is a betrayal of the teaching profession. By correcting their misconceptions, Professor Desai was not only deradicalising them but also humanising them. This is what all teachers should be doing in these times. Unfortunately, the authorities in power do not want this to happen.

In essence, it was not Professor Desai, but some of her students, who violated the norms of the classroom. The classroom is not a public forum; it is a space between the teacher and the students, created by them. It is more open and safer than the street, allowing free expression of views that may not be possible elsewhere. Here, thoughts can be shared that might lead to trouble outside. That is why teachers never make public the views expressed by students in the classroom, nor do they disclose their names. The classroom has to be a safe space, both for the students and the teachers.

Campuses and classrooms serve as laboratories of ideas. Teachers encourage students to speak their minds here because where else would they get such an opportunity? Inhibitions and censorship exist in every aspect of society, starting from the family.

The classroom is built on an unspoken contract between students and teachers, based on mutual trust. Just as students are allowed to present their views freely, teachers are also free to present their views. Their role is not to act as umpires in the game of ideas; rather, their training and position impose a more onerous responsibility on them. It is their duty to teach students how to think and how to think responsibly. That is precisely what Professor Desai was doing.

Self-censorship will impact teaching and learning

The students who recorded and made an edited version of the discussion public violated the contract between teachers and students, without which no class can function. By doing so, they not only endangered Professor Desai but also harmed other students. This includes not only the students in their college but also those in other institutions across India.

Now, teachers will become cautious and refrain from speaking out. They will begin self-censorship and distance themselves from the students. Popular opinion and mob mentalities will go unchallenged. This is a loss for teachers, but an even greater loss for students. If students are not encouraged and prompted to self-reflect, to critically examine themselves and their ideas in the light of reason, facts, and logic, how will they learn and what will they learn?

This incident in Kolhapur reminded me of Gilbert Sebastian from the Central University of Kerala, whose class presentation on fascism was also made public, similar to Professor Desai’s case. Organisations such as Akhil Bharatiya Vidyarthi Parishad forced the administration to suspend Sebastian. Although the suspension was later revoked, one can only imagine the impact it had on Sebastian. Will he be able to teach with the same ease after such an incident? Will he be able to teach with an open and fearless mind and heart?

If a teacher is constantly forced to doubt the intentions of her students and fears that anything they say might be broadcasted or that the authorities will be called upon them, then the classroom becomes an extremely tense environment. Without the freedom of honest speech, it will no longer be a place of genuine and open learning. The classroom will instead become a space for propaganda.

This is precisely what Hindutva organisations want the classroom to become. But is this what students also want?

(Apoorvanand teaches Hindi at Delhi University and writes literary and cultural criticism. His latest book is ‘Muktibodh Ki Lalten’. Courtesy: Frontline.)