Part I

Hundreds of thousands of Bhopal gas tragedy victims are eagerly hoping against hope.

They hope that the verdict in the civil curative petition number 345-347 of 2010 turns out in their favour and that all of them are awarded an enhanced compensation from the additional funds that the Union government is seeking from the US-based Dow Chemical Company.

Dow is the present owner of the Union Carbide Corporation (UCC) that is accused of causing the disaster of December 2-3, 1984, in Bhopal. It killed several thousands of people and inflicted injuries in varying degrees on more than half the then population of the city.

The victims had been exposed to highly poisonous gases – methyl isocyanate (MIC) and its derivatives – that escaped from the UCC plant due to installation of inadequate and improper safety systems. The adverse impact on flora and fauna was also equally grave.

However, from the manner in which hearings in the matter went on for three days – from January 10-12, 2023, it does not appear that the five-member constitution bench headed by Justice Sanjay Kishan Kaul has really understood the gravity of the situation faced by the gas victims.

While the bench of Justices Kaul, Sanjiv Khanna, Abhay S. Oka, Vikram Nath and J.K. Maheshwari may have made a sincere attempt to understand the background of the case in some detail, it is almost unlikely that it would have had the opportunity to go through 25 volumes of documents apart from thousands of pages of written submissions made by the various parties before the hearings began.

Therefore, first impressions gathered from oral submissions appear to have had a major role in the manner in which the hearings proceeded.

Misled?

It so happened that soon after the Attorney General for India, R. Venkataramani, began to make his submissions on behalf of the Union of India (UOI), Harish Salve, senior counsel representing Dow Chemical Company interrupted the AG and proclaimed, “My client is not willing to pay a farthing more.”

In an attempt to explain his stand, Salve also went on to misinform the apex court that not only were more than 573,000 gas victims paid compensation “twice over” but that an amount of Rs 50 crores was still lying unutilised in the settlement fund that UCC had paid in 1989.

Salve went on emphasising that out of the total number of victims who were awarded compensation, the UOI itself had admitted that over 500,000 of them had suffered only “minor injuries”. These assertions misled the court – at least initially.

The court was left with the impression that the Union of India was making unjustifiable additional claims.

Facts

The facts of the matter are quite different. Dow’s claim that the gas victims were paid compensation “twice over” is a cruel joke. The settlement amount of $ 470 million paid by UCC in February 1989 amounted to about Rs 710 crores considering the exchange rate then. This was nothing but a paltry sum considering the magnitude and gravity of the immediate impact of the disaster as well as its long term ramifications.

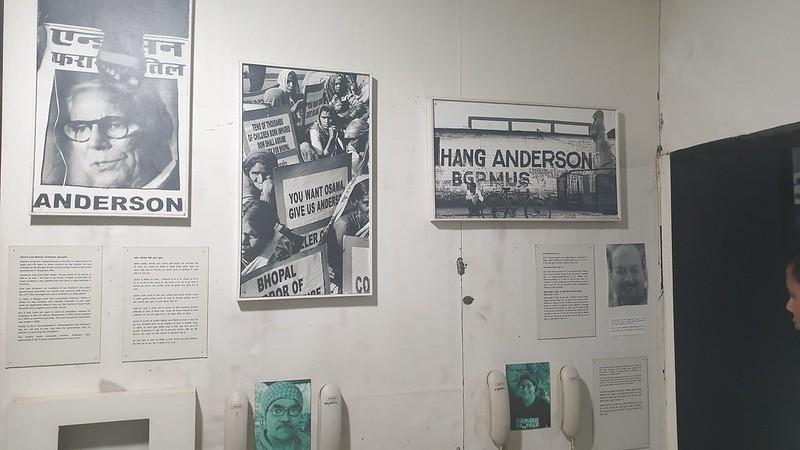

The unjust settlement was challenged by the Bhopal Gas Peedith Mahila Udyog Sanghathan (BGPMUS) on March 6, 1989, through a civil review petition filed through advocate Prashant Bhushan.

The BGPSSS filed a civil writ petition on March 9, 1989, against the settlement through advocate R.B.Mehrotra. A few other review and writ petitions were also filed subsequently. BGPMUS and Bhopal Gas Peedith Sangharsh Sahayog Samiti (BGPSSS) specifically urged the court “to pass consequential orders to give effect to the right to know and information on the toxicological, epidemiological and other related public health issues including the actual extent of the victimage in Bhopal.”

These review and writ petitions also pointed out that the settlement amount was quantified without verifying claims and without determining the number of beneficiaries to whom compensation was to be dispersed. Moreover, the settlement amount of Rs 710 crores was just about one-fifth of the amount claimed by the Union government in the amended suit that it had filed before the district court of Bhopal on January 29, 1988, which had clearly stated as follows:

“…[T]otal number of claims filed so far with the state government is 5,31,770…. It is estimated that approximate value of the total claims (including deaths and personal injury cases) would exceed Rs.3,900 crores (U.S. 3 billion dollars)…”

Justification

Since numerous questions were raised about the timing and the basis of the settlement, the Supreme Court found it necessary to justify its decision to order a settlement through a suo motu order dated May 4, 1989, which tried to clarify that the “basic consideration motivating the conclusion of the settlement was the compelling need for urgent relief”.

Therefore, in order to provide “urgent relief” to the victims, the settlement amount was quantified on the hypothetical assumption that only around 3,000 deaths had taken place and that around 102,000 others had suffered injuries in varying degrees. However, compensation could not be paid immediately to the said 105,000 gas victims since only a fraction of the assumed number of victims had been identified at that time.

Contrary to the justification that the settlement was intended to grant “urgent relief”, interim relief to the victims was actually disbursed by the Union government from 1990 to 1993 from its own resources and not from the settlement fund. The government allocated Rs 360 crores for that purpose at Rs 200 per month per head to all the residents in the 36 gas-affected wards of Bhopal. This benefited around 500,000 gas victims. Interim relief was further extended until 1996 and beyond due to delay in the process of adjudication for award of compensation.

In other words, the abrupt and unjust settlement could not and did not provide any immediate relief to the gas victims. The process of adjudication of the rising number of 600,000 and more claims started only after the judgment in the review petitions was pronounced on October 3, 1991. The process of adjudication went on from 1992 to 2004, during which an additional 400,000 and more claims were filed. After adjudication of all claims, the claim courts had determined that a total of 573,000+ victims had suffered injuries in varying degrees and there were 5,295 deaths.

As a result, compensation that was received for 105,000 victims (which was the basis of the settlement) was disbursed among 573,000+ victims.

The office of the Welfare Commissioner, under which the claim courts functioned, managed to pay small amounts of compensation to all the identified victims because the bulk of the settlement amount of US $ 470 million was retained in a dollar account in the Reserve Bank of India and that amount in rupee terms rose to over Rs 3,000 crores by 2004 (from Rs 710 crores in 1989) due to differences in exchange rate as well as accrual of interest from 1989 to 2004 on the principal sum.

Thus, by awarding low amounts of compensation, initially all the 573,000+ awarded claims were disposed of with just a little more than Rs 1,500 crores. Thereafter, the remaining amount was dispersed on a pro rata basis to the same number of victims as per the Supreme Court order dated July 19, 2004.

Effectively, this meant that each gas victim received less than one-fifth of the compensation that he or she should have received as per the terms of the settlement. This is because the settlement fund, which was quantified on the assumption that there were only 105,000 gas victims, was actually disbursed among five times that many (573,000+) gas victims, i.e., to 468,000+ additional gas victims, who were not recognised as gas victims at the time of the settlement.

Therefore, while Dow’s claim that the gas victims were paid compensation “twice over” may appear true, but the truth is that each gas victim on an average – despite being paid “twice over” – actually received less than one-fifth of the compensation amount that each should have received as per the terms of the 1989 settlement.

In other words, if the total settlement fund that amounted to Rs 3000+ crores (in 2004) was disbursed among the 105,000 gas victims (for whom the amount was earmarked in 1989), each gas victim on an average would have received over Rs 285,000 as compensation – which too was not a princely sum.

However, since the said amount of over Rs 3,000 crores was disbursed among over 573,000 gas victims in the year 2004, each gas victim on an average received merely a little above Rs 52,000 as full and final compensation (including pro rata), which amounts to a measly compensation sum of less than Rs 4 per day per victim for the last 38 years.

Similarly, Dow’s claim that Rs.50 crores is lying unutilised in the settlement fund is also a completely bogus claim, since the said Rs 50 crores is nothing but the unclaimed pro rata amount awarded to 11,652 gas victims, whose whereabouts are now not known because they are no longer at their last known address.

‘Minor’ injuries

Another matter told to the judges was the claim that over 500,000 gas victims, for whom additional compensation was being sought, had sustained merely “minor injuries”.

It is, indeed, true that in the Union government’s petition 5,27,894 victims are classified as having sustained only “minor injuries”. However, it is necessary to understand how the bulk of the gas victims came to be classified as such.

The process of so-called “medical categorisation exercise” began in January 1987, i.e., two years after the disaster. At that time, the vast majority of gas victims, who underwent treatment in hospitals and clinics immediately after the disaster, never possessed a copy of his or her medical records. Most of those who still undergo medical treatment, do not possess a copy of their medical records even 38 years after the disaster.

At the time of the settlement, less than 10% of the claimants had been medically evaluated for their personal injuries.

The so-called “medical categorisation exercise”, which was completed nearly two years after the settlement, i.e., about six years after the disaster, was more of a farce because all the necessary investigations were never carried out to determine the degree of injury sustained by the claimants almost six years earlier. Instead, excessive reliance was placed on post-disaster medical records, which most gas victims never possessed.

Ultimately, most victims were classed as having sustained “minor injuries” because they were able to prove that they resided in areas declared ‘gas-affected’. Indian Council of Medical Research survey reports, which were published subsequently, also prove that over 99% of those present in the 36-gas affected wards of Bhopal had, indeed, sustained injuries due to exposure to the toxic gases.

Delayed manifestations

Most gas victims have been unable to get rid of the “minor injuries” tag because they met the same fate before the claims courts as well, which adjudicated claims without the courts having access either to research findings of the ICMR regarding the impact of the disaster on the health of the gas victims or to the medical records of most of the individual claimants. However, it is significant that the Supreme Court itself in paras 128 and 129 of its judgment dated October 3, 1991, had observed as follows:

“On the medical research literature placed before us it can reasonably be posited that the exposure to such concentrations of MIC might involve delayed manifestations of toxic morbidity. The exposed population may not have manifested any immediate symptomatic medical status. But the long latency-period of toxic injuries renders the medical surveillance costs a permissible claim even though ultimately the exposed persons may not actually develop the apprehended complications.”

Unfortunately, the court only imposed an additional cost of a mere Rs 50 crores on the UCC in this regard, which UCC has not paid till date.

Inadequate medical surveillance

The government of India has also been lax in carrying out medical surveillance of the gas exposed population of Bhopal since 1991.

However, it is an admitted fact that every day on an average about 4,000 gas victims visit six hospitals and 18 clinics run by the Bhopal Gas Tragedy Relief & Rehabilitation Department (BGTRRD) of the state government.

In addition, on an average, every day, over 2,000 gas victims visit Bhopal Memorial Hospital & Research Centre and its eight units. By what stretch of imagination can these gas victims, who continue to visit gas relief hospitals and clinics (on more than 2,000,000 occasions every year even during the last two decades) for treatment of gas-related ailments, be classified as suffering from just “minor injuries” and as remaining just “temporarily injured” even 38 years after the disaster?

It is so unfortunate that proper and complete medical records of all these visits are not being properly maintained despite specific directions from even the Supreme Court vide judgment and order dated August 9, 2012.

The high court of Madhya Pradesh at Jabalpur in its order dated January 3, 2023 in a civil contempt petition of 2015 has also expressed concern at the fact that “merely about seventy-six thousand health books/medical records have been digitalized as against more than four lakhs gas victims to whom smart cards have been prepared/issued.”

Thus, medical documentation is in a pathetic state and yet the mass of the gas victims are still labeled as suffering from only “minor injuries”.

Part II

The lack of will to maintain proper and complete medical records of the victims of the Bhopal gas tragedy for the last four decades through digitisation or other means has been the biggest disservice to them.

This is the only method to determine the extent of the catastrophic nature of the injuries sustained by them. The problem has been compounded by the failure – in a large number of cases – to diagnose and categorise the type and gravity of injuries suffered by gas victims due to acute shortage of medical specialists both at Bhopal Memorial Hospital and Research Centre as well as Bhopal Gas Tragedy Relief and Rehabilitation Department hospitals. Available epidemiological survey reports highlight the gravity of the problem.

Morbidity and mortality rates

According to the ‘Technical Report on Population Based Long Term Epidemiological Studies Part-II (1996-2010)’ published by the National Institute for Research In Environmental Health (NIREH-ICMR) in 2013, the morbidity and mortality rates among the gas-affected population continue to be high.

| Level among 45-64 year olds | Morbidity rate in 1984 | Morbidity rate in 2010 |

| ‘Severely exposed’ | 99.43% | 45.01% |

| ‘Moderately exposed’ | 99.65% | 32.94% |

| ‘Mildly exposed’ | 99.59% | 27.73% |

| ‘Control area’ | 0.61% | 13.65% |

Subsequent age-group-wise morbidity rate is not available in the public domain.

As the table above shows, almost the entire population in the 36 gas-affected wards of Bhopal did inhale the toxic gases and did suffer certain degrees of injury.

Therefore, the assumption at the time of the settlement in 1989 that only 105,000 gas victims had suffered injuries (of whom 3000 died), had absolutely no basis. Over 468,000 gas victims were consciously and unjustly kept out of the ambit of the settlement despite of the fact that surveys conducted by the ICMR in 1984 had established that all of them had suffered injuries due to exposure to the toxic gases.

Moreover, data from the 58th Round of the Long Term Epidemiological Survey conducted by NIREH in February 2021 has revealed that the current “standardised mortality ratio (SRM) was found to be 114.2, 124.1, and 127.4 respectively in the severe, moderate and mild exposed areas.”

In other words, even 38 years after the disaster, mortality rate is still 14% to 27% higher in the gas-affected wards of Bhopal, which again proves that the real death figure due to the disaster would be far higher than the latest admitted death figure of 5479.

Considering the gravity of the long term impact of the disaster on the health of the gas-affected population of Bhopal, NIREH itself on page 34 of the said 2013 report had drawn the following conclusions:

“Hence it is recommended that newer studies on remaining population of the original total gas exposed population of 5,74,000 may be undertaken and extensive follow-up with major focus on clinical disease identification and treatment [be ensured].”

Unfortunately, there has been no follow up action in this regard for the last 10 years. The manner in which injuries sustained by the gas victims have been underplayed for the last four decades is astounding. Nevertheless, the Union government has now come forward to seek higher compensation for the victims.

Primary objective

It may be recalled that the primary purpose of the Union government in filing the curative petition in the Supreme Court was to implicitly challenge the direction in the judgment dated October 3, 1991, which had placed the onus on the Union government to make good the deficiency in the settlement fund, if any.

The direction was as follows:

“…[I]n the – perhaps unlikely – event of the settlement-fund being found inadequate to meet the compensation determined in respect of all the present claimants…the reasonable way to protect the interests of the victims is to hold that the Union of India, as a welfare State and in the circumstances in which the settlement was made, should not be found wanting in making good the deficiency, if any. We hold and declare accordingly.”

Since the Union government realised that the magnitude of the disaster was far greater than what was assumed at the time of the disaster, it invoked a part of the suo motu order dated May 5, 1989, which had granted a ray of hope to the gas victims with the following assurance to undo any injustice:

“If, owing to the pre-settlement procedures being limited to the main contestants in the appeal, the benefit of some contrary or supplemental information or material, having a crucial bearing on the fundamental assumptions basic to the settlement, have been denied to the Court and that, as a result, serious miscarriage of justice, violating the constitutional and legal rights of the persons affected, has been occasioned, it will be the endeavour of this Court to undo any such injustice. But that, we reiterate, must be by procedures recognised by law. Those who trust this Court will not have cause for despair.”

The Union government had filed the curative petition specifically to seek compensation for the more than 468,000 victims, who were left out of the ambit of the settlement but whose right to be awarded compensation was subsequently established by the claims courts.

The government had also sought to recover the sums that it had spent for providing relief and rehabilitation to the gas victims, including ex gratia payments. As of now, the entire settlement amount of Rs 3,000 crores (including interest and difference in exchange rate), which should only have been paid to 105,000 gas victims (as per the terms of the settlement), has been shared with over 468,000 other victims, who were unjustly excluded from the ambit of the settlement.

The plea of the two bodies, BGPMUS and BGPSSS, is that the quantum of additional compensation also be based on the degree of injury suffered by each of the 573,000+ gas victims (as corroborated by their medical records). BMHRC is reportedly maintaining medical records of 4.5 lakh gas victims. However, most of it has not yet been digitised or networked with the medical records reportedly being maintained by BGTRRD hospitals. As of now, copies of respective health records have been shared with just a few gas victims.

Bhopal Gas Peedith Stationery Mahila Karamchari Sangh or BGPSMKS and four other organisations representing gas victims also intervened to support the petition. Senior advocate Sanjay Parikh represented BGPMUS and BGPSSS and Karuna Nandy represented BGPSMKS and others.

Short hearing

While hearings in the petitions challenging the constitutional validity of the Bhopal Gas Leak Disaster (Processing of Claims) Act, 1985, continued for 27 days before a constitutional bench and hearings in the review petitions challenging the Bhopal settlement continued for 19 days before another constitutional bench, the hearings in the Bhopal disaster curative petition were completed in just three days.

While the Attorney General for India was permitted to argue for seven and a quarter hours, Nundy was allotted 40 minutes and Parikh was allotted 50 minutes. Salve, for Dow Chemical which owns Union Carbide now, was allotted 80 minutes in addition to the time he took to interrupt the AG on several occasions.

The time allotted for the hearing appears to have been too short to establish whether or not Union Carbide was liable to pay additional amounts to meet the shortfall.

As to whether there was a shortfall at all in the settlement fund was also not examined. The bench also refrained from examining whether “…material, having a crucial bearing on the fundamental assumptions basic to the settlement, have been denied to the Court and that, as a result, serious miscarriage of justice, violating the constitutional and legal rights of the persons affected, has been occasioned…”

The bench appears to have taken the view that if there was a shortfall, it was the Union of India’s obligation to make good the deficit.

Regarding the assurance granted to the victims in para 38 of the suo motu order dated May 4, 1989, the bench declined to express any specific view. Moreover, the bench refrained from examining if the settlement ever provided “immediate and substantial relief to the victims of the disaster…”.

It also refrained from examining if the settlement was at all “just, equitable and reasonable” despite the fact these were the stated objectives of the Supreme Court when it ordered the settlement on February 14, 1989. Although “(t)he Court directed the settlement with the earnest hope that it would do them good”, the bench refrained from examining if at all the settlement did any good to the gas victims.

To the gas victims’ grave disadvantage, the bench somehow chose not to examine all the relevant aspects relating to the case, which had not been examined earlier because those relevant materials were not available at the time when the review petitions were being heard three decades ago in 1991.

Instead, the bench sought to limit the scope of the hearing because it was apparently more concerned with upholding the “sanctity of the settlement”. The bench seemed to express the view that it would not like to interfere with the matter since it was a mutually agreed settlement between two parties, namely the Union government and Union Carbide Company. However, the facts in this regard appear to be quite different.

Parikh’s Submission

Recounting the events that led to the settlement, Senior Advocate Sanjay Parikh, who appeared on behalf of BGPMUS and BGPSSS, submitted:

“The settlement was…not an ordinary settlement in a suit between two parties. It was an order of the Court which was accepted by the parties.”

This assertion is very evident from the court’s order itself. In the order dated February 14, 1989, the court had clearly observed as follows:

“Having given our thoughtful consideration for several days…[and due to the] pressing urgency to provide immediate and substantial relief to the victims…we hold it just, equitable and reasonable to pass the following order”.

It was the court, which had determined the quantum of the settlement amount of US $ 470 million on the assumption that it was a reasonable sum. The court had also ordered that: “A memorandum of settlement shall be filed before us tomorrow…” (which the parties, the Union of India and Union Carbide Company, subsequently filed before the court).

In other words, the memorandum of settlement was signed between the Union and UCC in response to the court’s directions in the order dated February 14, 1989 and not earlier.

Thereafter, in the last para of the same order, the court records its appreciation for the parties “in accepting the terms of settlement suggested by this Court”. In short, Parikh argued, it was a court-ordered settlement.

Explaining the point further, Parikh said: “It was for this reason that justification was provided suo moto by this Court in its order and judgement dated 4th May 1989 [1989 (3) SCC 38] as to how the sum of US $ 470 million was arrived at.”

If it was merely a mutually agreed settlement between two parties, there would have been no need or occasion for the court to offer any such justification. In fact, the 1989 suo motu order makes it abundantly clear that the court retained absolute power to initiate proceedings to suo motu set aside the order dated February 14, 1989, in the interest of justice. The said para categorically stated as follows:

“We should make it clear that if any material is placed before this Court from which a reasonable inference is possible that the Union Carbide Corporation had, at any time earlier, offered to pay any sum higher than an out-right down payment of US 470 million dollars, this Court would straightaway initiate suo motu action requiring the concerned parties to show cause why the order dated 14 February, 1989 should not be set aside and the parties relegated to their respective original positions.”

Ordinarily, the court would have had no power to interfere with a mutually agreed settlement by two parties. However, in the case of the Bhopal disaster matter, the court retained absolute power to modify or abrogate that settlement in the interests of justice precisely because it was a court-ordered settlement.

Parikh’s objective in highlighting these aspects was to emphasise that: “The orders dated 14/15.2.1989 were passed by the Supreme Court directing settlement in exercise of its plenary power and under Article 142 of the Constitution.”

Parikh also brought to the attention of the bench that in the judgment dated October 3, 1991, on the review petitions, the constitution bench had again exercised its plenary jurisdiction and powers under Article 142 to modify the settlement orders dated February 14-15, 1989.

Parikh noted that after considering the contentions in the review petitions, the court reviewed the settlement in 1991 and “the quashing and termination of criminal proceedings brought about by the Settlement order was set aside. Similarly, the part of the settlement relating to immunity from future criminal liability was also set aside.

Apart from these modifications in the settlement orders dated February 14-15, 1989, the constitution bench that heard the review petitions had also acknowledged the possibility of “delayed manifestations of toxic morbidity” of the judgment dated October 3, 1991 as noted above. Accordingly, the court highlighted the need for medical surveillance and directed UCC to pay an additional Rs 50 crores for that purpose as noted in the judgment dated October 3, 1991, which was another decision that explicitly modified the terms of the settlement in order to render justice.

All these examples prove that the court had exercised its powers under Article 142 and modified the Bhopal settlement to serve the interests of justice. Nothing prevents the present constitution bench from exercising those powers and modifying the settlement again in the interest of justice after duly examining all the facts and figures relating to the case, which were not before the Court at the time of passing its judgment in the review petitions in 1991.

It may be noted that the adverse impact of the disaster did not disappear soon after the disaster in 1984; its toxic impact in Bhopal continues to persist even nearly four decades later. Since the long term impact of the disaster on the gas victims and its wider ramifications had not been taken into consideration at the time of the settlement and was underplayed when the review petitions were being heard, the plea is that the constitution bench should exercise its powers under Article 142 of the constitution to incorporate the omissions judiciously by suitably modifying the settlement in the best interests of rendering justice.

Harish Salve, for Dow, vehemently opposed the curative petition stating that the prayers in it tantamount to reopening the settlement.

Nevertheless, the AG, in his concluding remarks, stated that para 38 of the May 4, 1989 order could not be interpreted in any other manner than as a reopener clause. The said order was also passed by a constitution bench. Can a similar bench overrule or sidestep that assurance granted to the victims? The fate of the curative petition will depend on the manner in which the present constitution bench chooses to give weightage to the said para.

In addition to the disaster that has had grave impact on all living things, dumping of toxic waste while the Union Carbide plant was in operation from 1969 to 1984 had severely contaminated soil and ground water in and around the plant in Bhopal. A writ petition is currently pending before the Madhya Pradesh high court, seeking to hold them responsible.

The fact is that there has been serious miscarriage of justice. Whose responsibility is it to set it right?

(N.D. Jayaprakash is Joint Secretary, Delhi Science Forum and Co-Convener, Bhopal Gas Peedith Sangharsh Sahayog Samiti (BGPSSS). Courtesy: The Wire.)