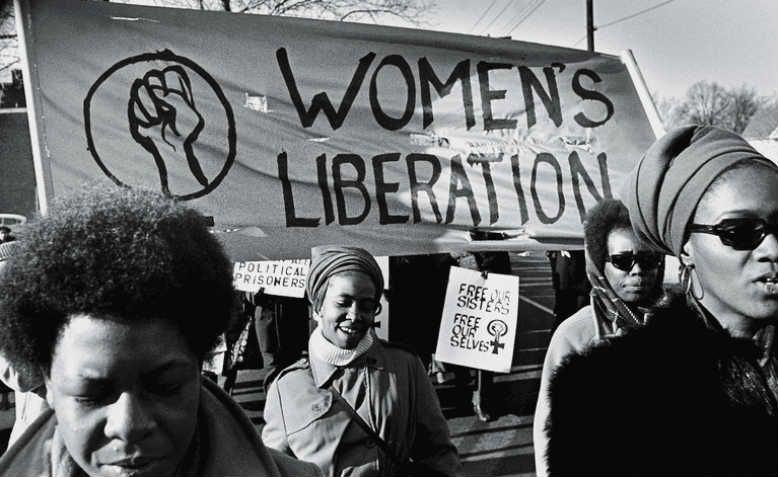

Today, International Women’s Day is widely celebrated. Big companies, institutions and media outlets will all be keen to join the occasion. These high-profile celebrations of a day founded by socialists to highlight the struggles of working-class women will not include any discussion of socialism, nor will they contain much about the specific problems and experiences of working-class women.

Let’s see an example of how this works in practice. This year, one London university is holding an International Women’s Day event focussing on women (former students) who have careers in predominantly male-dominated spheres.

Titled ‘Alumni Angels’, this doesn’t really sound like a description of working life or reflective of women’s struggle to be taken seriously (and it brings this author flashbacks of insecure temp work supposedly brightened up with fluffy pens as an ‘office angel’). The publicity states: ‘Equality is not a women’s issue, it’s a business issue.’ It is painfully ironic that staff at this university are currently on strike in part because of the gender pay gap there. Ripped from its origins in the struggle for working women’s rights, International Women’s Day is in danger of becoming a marketing strategy for employers.

Yet it was precisely to challenge a version of feminism that focussed on women at the top of society, and ignored the needs of working-class women, that International Women’s Day was created in the first place. Remembering the origins of International Women’s Day helps us to face the challenges of struggling against women’s oppression in a class divided society today.

The debate: should socialists support votes for women?

At the beginning of the twentieth century, feminist movements were revitalised by the growing demand for women’s suffrage. The call for ‘votes for women’ did not, however, produce a united women’s movement. Campaigners were divided over the question of votes for which women.

In the United States, where demands for women’s suffrage had arisen in conjunction with the anti-slavery movement, by the beginning of the twentieth century leading campaigners were using explicitly racist arguments to try to advance their campaign. For example, Belle Kearney (later the first woman elected to the Mississippi State Senate), argued in the National American Women’s Suffrage Association, that ‘The enfranchisement of women would insure immediate and durable white supremacy’.[1] Promoting women’s suffrage as a bulwark against black male voters (and denying any representation for black women), Kearney and other leading campaigners presented women’s suffrage as a means of better safeguarding the inequalities and discriminations of the status quo.

In Britain, the divisions had been sown by property qualifications imposed as a condition for the right to vote. By the beginning of the twentieth century, no woman had the right to vote in general elections, but neither did the poorest men who were excluded by the property requirements.

When most women’s suffrage organisations called for votes for women ‘on the same terms as it is or may be granted’ to men, they justified it on the basis that it represented a principled demand for equality.

It seemed to many of the campaigners as a pragmatic compromise: as the most realistic way of achieving change. But it appeared so because it did not explicitly challenge private property – the root of capitalist society. In difficult circumstances, the campaigners had nevertheless made a choice: to present women’s suffrage as essentially compatible with the status quo wherein the source of exploitation would be maintained, rather than ally with the poorest men and women to challenge it.

This compromised position was challenged by socialist women who stood for the abolition of class divided society.

Klara Zetkin and Alexandra Kollontai were two of the leading socialist theorists of women’s oppression at the beginning of the twentieth century. They acknowledged that all women experienced women’s oppression, but they also argued that in a capitalist society, women did not experience that oppression in the same way, nor did they share the same interests. Whereas the most economically privileged, bourgeois women wanted equality with men of their own class, it was hardly in the interests of working-class women to fight for equality with working-class men, rather it was in their interest to fight with working-class men to dismantle the structures of class society.

They therefore argued that it would be a mistake for socialists to endorse limited campaigns for women’s rights which were uninterested in achieving working women’s emancipation. Kollontai warned that, once the vote was won, bourgeois women would ‘become enthusiastic defenders of the privileges of their class’.[2]

In 1907, Zetkin initiated the first of the International Socialist Women’s Conference to immediately precede the meeting of the Second International, where representatives from left parties gathered from across the world. Zetkin and Kollontai used the occasion to argue against campaigns for partial women’s suffrage and they won the conference to support a resolution stating: ‘socialist parties of all countries have a duty to struggle energetically for the introduction of universal suffrage for women.’[3]

From the American sweatshops

The importance of a socialist women’s movement was also being felt across the Atlantic.

One woman who felt this way was Theresa Malkiel. Born to a Jewish family in 1874 in Ukraine, then under the control of the violently antisemitic Russian Empire, she moved to the United States with her family in 1891, joining thousands of other immigrant workers in New York’s Lower East Side. Like them, she had little choice but to work in a sweated industry. She became a cloak maker and immediately began to unionise her workmates, becoming the first president of the Infant Cloakmakers’ Union of New York.

Malkiel joined the Socialist Party and became a leading activist, journalist and organiser. She argued that working-class women found themselves ‘between two fires’: the capitalist class, her ‘bitterest enemy’, but also a complacency from ‘her brothers’ about the importance of challenging women’s oppression: ‘We are told very often to keep quiet about our rights and await the social millennium.’[4] Malkiel insisted that they were part of the same struggle and that to overlook women’s rights was to weaken the whole struggle for social emancipation.

Malkiel argued against the complacency on women’s rights inside the Socialist Party and persuaded the organisation to organise a ‘Woman’s Day’, when they would hold mass meetings for women’s suffrage. The first were held on Sunday 28 February 1909 in New York. Woman’s Day became an annual event, held on the last Sunday of February – a Sunday to ensure workers could attend.

Like Zetkin and Kollontai, Malkiel believed it was important for socialists to champion the right to vote not as an end in itself, but as a means of winning social and economic equality. She explained it using a metaphor from her own trade:

“The ballot, though an absolute necessity in her struggle for freedom, is only one of the aims toward her goal. We cannot renovate a garment by turning over one of the sleeves – the whole of it must be turned inside out.”[5]

Within nine months of the first Woman’s Day, working-class women demonstrated their capacity to shake the foundations of American capitalism. Beginning with ‘the uprising of the 20,000’, a strike led by immigrant women workers in the sweated garment trade in New York, a wave of similar strikes broke out in city after city from 1909 to 1915 which took on the employers, the judiciary, the police, the press and hired thugs.

To European international socialism

In 1910, the International Socialist Women’s Conference, meeting in Copenhagen, seized upon the example of American socialist women. The call for a day for socialists to champion women’s rights came from two members of the German SPD, the largest socialist party in Europe: it was proposed by Luise Zietz, a member of the Unskilled Factory Workers’ Union, and seconded by Klara Zetkin.

Reflecting the internationalism of its founding event, this day was to transcend national boundaries. The first International Women’s Day was held on 18 March 1911 – forty years after the revolutionary Paris Commune was proclaimed.[6]

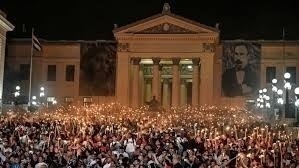

In 1871 working-class Parisians rose up against the invading Prussian army and the capitulating French government and installed a government of their own representatives. For the 72 days it lasted before it was brutally crushed by the French army, the Paris Commune provided a glimpse of a different kind of society. The changes extended to women’s lives, crucially in dismantling the differentiation between ‘illegitimate’ and ‘legitimate’ children. Women played a leading role in the Commune and were particularly savagely targeted its suppression.

In an expression of international solidarity, those commemorating the French communards on the first International Women’s Day were women in Germany (formerly part of Prussia), Denmark, Switzerland and Austria.

Kollontai recalled that the first International Women’s Day surpassed all expectations; in Germany and Austria cities, towns and villages were transformed into ‘one seething, trembling sea of women’.

For a day, the world was turned upside down: ‘Men stayed at home with their children for a change, and their wives, the captive housewives, went to meetings.’[7]

The impact: Sylvia Pankhurst in Britain

As we have seen, International Women’s Day was initiated as a socialist call for women’s suffrage. In Britain, the socialist Sylvia Pankhurst was growing increasingly disillusioned with the rightward political trajectory of the women’s suffrage movement there.

Sylvia Pankhurst encountered Woman’s Day when she was touring America on a women’s suffrage lecture tour in 1911. On 23 February, socialist women in Boston proposed an evening torchlit march on the State House alongside local suffragists. Sylvia Pankhurst marched in the front row of a demonstration that included immigrant women from Latvia and Finland, and members of Harvard’s socialist student club.

The following year, Pankhurst began to try to build groups composed of working-class women from East London inside the militant suffragette organisation the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU). The socialist politics she represented were rejected by the WSPU who expelled Pankhurst and her East London groups in January 1914.

They established themselves independently as the East London Federation of Suffragettes and soon began to campaign for votes for all women – and later for ‘human suffrage’: all men and all women. They introduced themselves with a march on Downing Street and the publication of their own newspaper, the Woman’s Dreadnought.

The date they chose for the demonstration and the first issue of the Dreadnought was 8 March 1914. One year earlier, 8 March had been fixed as the permanent day for International Women’s Day.

The impact: the Russian Revolution

1913 was the first year that International Women’s Day was organised in Russia (where it was called ‘Working Women’s Day’).

It was illegal under the Tsarist dictatorship, but the socialists were determined to celebrate the day; articles were published in the newspapers of the socialist Bolshevik and Menshevik parties and a secret meeting was held. At the end of the meeting, the police rushed in and arrested many of the speakers.

The following year, Kollontai recalled ‘[t]hose involved in the planning of “Women Workers Day” found themselves in the Tsarist prisons, and many were later sent to the cold north.’[8] But the socialists did not stop commemorating International Women’s Day.

During the First World War, this overtly internationalist celebration took on renewed radical significance as a counter to nationalism and militarism. It became instead a way to express the sentiment articulated best by the socialist Karl Liebknecht – that the main enemy was not abroad but at home.

In Russia, this feeling towards the Tsarist state was only intensified by the War. By 1917, facing a seemingly endless and pointless war of attrition on the battlefields, and devastating food shortages at home, Russian women in St Petersburg decided to protest. The day they chose for their protest was International Women’s Day: 23 February in the Russian calendar, it was 8 March in the western European Gregorian calendar.

Women marching openly through the streets in Russia signalled that everything had changed. On the first day they demanded bread, by the second day they demanded an end to the autocracy and an end to the war. The Russian Revolution had begun – on International Women’s Day.

International Women’s Day now

The day we celebrate on 8 March was created by socialists who insisted that working-class women’s interests should not be subordinated to the narrow gains envisaged by a small minority of women. They understood that working-class women’s emancipation necessitated the overthrow of the structures of inequality and oppression – a revolutionary potential that was realised in the Russian Revolution. The creators of International Women’s Day teach us that corporate attempts to capitalise on the day have nothing in common with our struggle.

Today, of all days, we shouldn’t be asking how many women are in the boardroom, but why it is that it will be women, disproportionately BAME women, on poverty wages, that are cleaning that boardroom. And on Monday, we should be joining the picket lines alongside the UCU strikers for equal pay.

Notes

[1] Quoted in Angela Y. Davis, Women, Race and Class (New York: Vintage Books, 1983), p.125.

[2] Alexandra Kollontai, The Social Basis of the Woman Question, 1909

[3] Quoted in Tony Cliff, Class Struggle and Women’s Liberation 1640 to today (London: Bookmarks, 1984), p.77.

[4] Theresa Malkiel, ‘Where Do We Stand on the Woman Question?’ International Socialist Review, 10, August 1909, p.160, p.161.

[5] Quoted in Annelise Orleck, Common Sense and a Little Fire: Women and Working-Class Politics in the United States, 1900-1965 (Chapel Hill; London: The University of North Carolina Press, 1995), p.95.

[6] Temma Kaplan, ‘On the Socialist Origins of International Women’s Day’, Feminist Studies, 11 (September 1986), p.167.

[7] Alexandra Kollontai, International Women’s Day, 1920

[8] Alexandra Kollontai, International Women’s Day, 1920

(Katherine Connelly is a writer and historian. She led school student strikes in the British anti-war movement in 2003, co-ordinated the Emily Wilding Davison Memorial Campaign in 2013 and is a leading member of Counterfire, a British socialist organisation and newsletter. Article courtesy: Counterfire.)