The Allahabad high court judgment dismissing a PIL asking for the removal of the Shahi Idgah in Mathura is a relief, even though it is on the technical ground that similar petitions are pending before it. Given the Supreme Court’s willingness to entertain an archaeological survey of the Gyan Vapi Mosque in Varanasi and a challenge to the Places of Worship Act 1991, both the Gyan Vapi mosque and Shahi Idgah may still go the way of the Babri Masjid. The template is set – a local dispute elevated to a national issue, a self-appointed next friend of the idol, a court-mandated archaeological survey, and a judiciary which values faiths differentially.

When Chief Justice of India (CJI) D.Y. Chandrachud argued that ascertaining the religious character of a place was not barred under the Places of Worship Act, and agreed to examine the Act itself, he reneged directly on a commitment the Supreme Court had made barely a few years ago. In an otherwise disappointing judgement, handing over the site of the Babri Masjid to the very people who vandalised it, a five-judge bench of the court reiterated the importance of the Places of Worship Act of 1991:

“In providing a guarantee for the preservation of the religious character of places of public worship as they existed on 15 August 1947 and against the conversion of places of public worship, Parliament determined that independence from colonial rule furnishes a constitutional basis for healing the injustices of the past by providing the confidence to every religious community that their places of worship will be preserved and that their character will not be altered. The law addresses itself to the State as much as to every citizen of the nation. Its norms bind those who govern the affairs of the nation at every level. Those norms implement the Fundamental Duties under Article 51A and are hence positive mandates to every citizen as well. The State, has by enacting the law, enforced a constitutional commitment and operationalized its constitutional obligations to uphold the equality of all religions and secularism which is a part of the basic features of the Constitution. The Places of Worship Act imposes a non-derogable obligation towards enforcing our commitment to secularism under the Indian Constitution. The law is hence a legislative instrument designed to protect the secular features of the Indian polity, which is one of the basic features of the Constitution. Non-retrogression is a foundational feature of the fundamental constitutional principles of which secularism is a core component. The Places of Worship Act is thus a legislative intervention which preserves non-retrogression as an essential feature of our secular values.” [Emphasis supplied]

If the law’s “norms bind those who govern the affairs of the nation at every level”, this presumably includes the highest judiciary. Enabling the buildup to a demand for the conversion of the Gyan Vapi Mosque or the Shahi Idgah, judicially or otherwise, should really be classified as abetment under the Places of Worship Act, punishable by three years imprisonment and fine. But who will jail the judges and who will bind them to obey their own stated norms?

BJP politician and serial PIL petitioner Ashwini Upadhyay’s challenge to the Places of Worship Act rests on the grounds that by making 1947 the cut-off date on which all claims to restoration of places of worship would cease, it bars judicial redress; and that destroyed temples are really still temples and ‘restoring’ them would not involve conversion. This is the ghar wapsi argument, used to escape culpability when it comes to Hindu conversions of Adivasis, now being applied to Hindu temples.

Upadhyay’s petition is deeply offensive with its reference to ‘Hindus, Jains, Buddhists and Sikhs’ as the only victims, the language of ‘fundamental barbaric invaders’, and the argument that 1192 (Ghurid invasion) should be the cut-off date rather than 1947 for restoration of places of worship. A self-respecting constitutional court – which owes its very existence to independence in 1947 and the Republic it enshrined – should have thrown out the petition on this ground alone. One might also ask why 1192? Why not go back to the advent of the Aryans and the “intentional” damage and smashing of Harappan sites of worship, as detailed by the archaeologist R.S. Bisht?

There are three issues at stake here: the conception of history that is being enshrined in the courts through such cases; the question of faith; and the question of who is entitled to judicial redress and how. But before that, it would be useful to go back to the Lok Sabha debates on the Places of Worship Act on September 9 and 10, 1991, which make fascinating reading.

Parliamentary debates on the Places of Worship Act

The Places of Worship Bill was brought in as part of a commitment made in the Congress manifesto, as a response to the communal buildup created by L.K. Advani’s Rath Yatra, and the purchase of land by the Kalyan Singh government next to the Babri Masjid. The Act prescribes 1947 as the cutoff date to maintain status quo for all places of worship, abates all existing disputes as of this date; makes an exception for the Ramjanmabhoomi-Babri Masjid, buildings under ASI governance and cases settled by mutual acquiescence or judicial decree prior to the Act, and prescribes a punishment of up to three years and a fine, for any kind of involvement in converting a religious shrine to that of another faith or denomination.

Interestingly, this was not the first time this principle was asserted. The religious sites of another faith, like the women of a community, have always been among the first objects of attack in a communal riot. As Anil Nauria has pointed out, at the 1924 Unity Conference, following riots in Delhi, a ‘Resolution on Religious Toleration’ passed on October 2, 1924 stated:

“That all places of worship, of whatever faith or religion, shall be considered sacred and inviolable, and shall on no account be attacked or desecrated, whether as a result of provocation or by way of retaliation for sacrilege of the same nature. It shall be the duty of every citizen of whatever faith or religion, to prevent such attack or desecration as far as possible and where such attack or desecration has taken place, it shall always be promptly condemned.” [Indian Annual Register, 1924 (Vol 2), p. 156]

Again, after the illegal installation of the Ram Lalla idol inside the Babri Masjid in 1949, Pandit Sunderlal organised a Qaumi Ekta Sammelan (Religious Unity Convention) in 1950, in which Acharya Narendra Dev passed a resolution defending status quo in respect of all places of worship from 1947.

The 1991 debate over the Places of Worship Act was marked by some drama. Even before it was presented, BJP members objected; they frequently interrupted MPs speaking in support of the Bill, threw a paan wrapper at one MP, threatened to “see people outside the house” and finally walked out. BJP MPs insisted that the Bill was not going to settle disputes; demanded that the Kashi Gyan Vapi mosque and Mathura Idgah also be excluded along with the Babri Masjid; and asked why the Bill would not be applicable to J&K.

Uma Bharti asserted that she felt wounded and inferior when she saw a mosque next to a temple. Mani Shankar Iyer countered this by saying that for him the same image created pride in India’s composite heritage. Others also defended the Bill as essential for secularism, pointing out the Hindus had destroyed Buddhist and Jain shrines.

Ram Vilas Paswan and Somnath Chatterjee pointed to Congress’s complicity in opening the locks of the Babri Masjid. While the BJP wanted the Ramjanmabhoomi to be handed over not by the courts, but by the power of Hindu faith, Congress MPs called for a speedy judicial resolution to the issue that both sides would have to accept. A few non-Congress MPs, however, questioned the exclusion of the Babri Masjid from the Bill, given that it was the immediate cause of action!

Some BJP MPs questioned 1947 as the cut-off date arguing that the real cut-off date should be the 12th century, but other MPs stoutly defended August 15, 1947 because that was the date on which a new future was forged for the country.

An important question raised by some Muslim MPs – P.M. Sayeed, Ebrahim Sulaiman Sait and Sultan Salahuddin Owaisi – was whether it was simply conversion to another place of worship that would count or any change in the nature of the place. This was rooted in the experience of Muslim sacred spaces post-partition. As Indrajit Gupta pointed out, several mosques and dargahs in Punjab had been taken over for residential buildings, cow sheds and other such purposes. Yunus Saleem also asked for protection to tombs, graveyards and other such sites which were not strictly objects of worship, but nevertheless sacred. (Of course, a BJP MP objected to the very idea of ever giving such spaces back to Muslims.)

The home minister responded by saying that clause 4 (1) covered this by providing for the “continuance of the religious character of a place of worship existing on the 15th day of August, 1947.” However, penal action is prescribed only for conversion to another place of worship.

When the Supreme Court considers the challenge to the Act, it would do well to remember that it represents the legacy of the freedom movement, the secular principles of a former socialist leader from Ayodhya, Acharya Narendra Dev, and the majority view of an earlier house.

Judicial appreciation or desecration of history?

It is interesting how often judiciaries are called upon to exercise historical judgments, and how they claim expertise in doing so. For instance, while hearing the Gyan Vapi case, the Supreme Court noted that it would consider the ASI report as it had done in the Ayodhya case, ‘separating the grain from the chaff’, even as it discounted the views of non-ASI professional archaeologists. In the Ayodhya judgment, there was also no mention of the immediate historical context in which Ramjanmabhoomi became an issue – who pulled the mosque down, etc. Indeed, the judgment ruled it irrelevant (para 429). To any professional historian, this is a surprising omission.

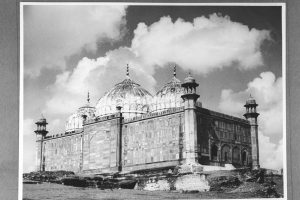

History in multicultural, multi-religious and ancient societies like India, is a complicated issue. Take the history of the Gyan Vapi itself. In an essay on entangled histories in Benaras, Madhuri Desai points out that there was no archaeological or recorded evidence of a Visheshwur temple before the 15th century. The temple that was ordered to be destroyed by Aurangzeb in 1669 was a temple that had been built under Mughal patronage circa 1590. Yet this earlier patronage is forgotten by the Hindu right and only the destruction is highlighted.

Whether Aurangzeb demolished the temple because a Hindu queen from Kutch was dishonoured there as Pattabhi Sitrammaya reported in his book Feathers and Stones is a moot question today. What is more important is that in 2022 Ravi Kant, a Hindi lecturer at Lucknow University, was attacked by the ABVP and an FIR lodged against him for quoting from Sitarammaya’s account. Is the right to discuss history now going to be limited to only one ideology?

Subsequent rebuildings of the temple adjacent to the Mosque were propelled by Maratha politics, which needed to weaponise Hinduism as part of their anti-imperial struggles. Even later, as ethnographer Vera Lazaretti shows, the pilgrimage around the Jnana Vyapi well and maidan was the subject of much litigation over decades by the Vyas family trying to claim exclusive rights, and it is this local dispute which has been picked up and magnified by the RSS. But as Lazaretti writes, ironically the Vyas family themselves have been displaced by the Kashi Vishwanath corridor, and their role as litigants taken over by lawyer Vijay Shankar Rastogi as the new “next friend” of Kashi Vishwanath.

Religious desecrations as conquest

Muslim destruction of Hindu shrines was clearly not the only form of religious destruction. Fight between Shaivites and Vaishnavites, between different denominations within Christianity and Islam – all led to destruction of each other’s place of worship. Richard Davis shows how the taking of idols or images from subjugated rulers and placing them in one’s own buildings was a routine act, indeed one that was sanctified by Manu. By contrast, temple desecration was more limited, but there too, it was done by rulers as part of conquest; precisely because temples were political symbols, with the tutelary deity expressing the sovereignty of both the God and King. Richard Eaton provides an illustrative list of instances where Hindu kings destroyed temples:

“In A.D. 642, according to local tradition, the Pallava king, Narasimhavarman I, looted the image of Ganesha from the Chalukyan capital of Vatapi. Fifty years later, armies of those same Chalukyas invaded North India and brought back to the Deccan what appear to be images of Ganga and Yamuna, looted from defeated powers there. In the eighth century, Bengali troops sought revenge on King Lalitaditya by destroying what they thought was the image of Vishnu Vaikuntha, the state deity of Lalitaditya’s kingdom in Kashmir. In the early ninth century, the Rashtrakuta king, Govinda III, invaded and occupied Kanchipuram, which so intimidated the king of Sri Lanka that he sent Govinda several (probably Buddhist) images representing the Sinhala state. The Rashtrakuta king then installed these in a Saiva temple in his capital. About the same time the Pandyan king, Srimara Srivallabha, also invaded Sri Lanka and took back to his capital a golden Buddha image-” a synecdoche for the integrity of the Sinhalese polity itself “-that had been installed in the kingdom’s jewel palace. In the early tenth century, the Pratihara king, Herambapala, seized a solid gold image of Vishnu Vaikuntha when he defeated the Sahi king of Kangra. A few years later, the same image was seized from the Pratiharas by the Candella king, Yasovarman, and installed in the Lakshmana temple of Khajuraho. In the early eleventh century, the Chola king, Rajendra I, furnished his capital with images he had seized from several prominent neighboring kings: Durga and Ganesha images from the Chalukyas; Bhairava, Bhairavi, and Kali images from the Kalingas of Orissa; a Nandi image from the Eastern Chalukyas; and a bronze Siva image from the Palas of Bengal. In the mid-eleventh century, the Chola king, Rajadhiraja, defeated the Chalukyas and plundered Kalyani, taking a large black stone door guardian to his capital in Thanjavur, where it was displayed to his subjects as a trophy of war.

“While the dominant pattern here was one of looting royal temples and carrying off images of state deities, we also hear of Hindu kings destroying the royal temples of their political adversaries. In the early tenth century, the Rashtrakuta monarch, Indra III, not only destroyed the temple of Kalapriya (at Kalpa near the Jamuna River), patronized by the Rashtrakutas’ deadly enemies, the Pratiharas, but they took special delight in recording the fact.” (Eaton, Temple Desecration, pg 105)

There was, therefore, nothing unique about Muslim rulers destroying temples. Why do RSS petitions never use the same language of “barbaric invaders” against these Hindu medieval kings? The figures of temple destructions are also significantly lower than is claimed by the Hindutva believers. Moreover, temple destruction, when it did occur, was directed by rulers at temples associated intimately with other rulers, and not by ordinary Muslims or Hindus. Compare this to the present, when every Hindutva ideologue feels entitled to punish every ordinary Muslim.

Hindu replacement of Buddhist shrines is a widespread phenomenon, and not all of this was peaceful. Caves 14 and 15 of the Ellora caves were originally Buddhist viharas which were then converted to Hindu shrines. It now emerges from a Madras high court order of 2022 that the idol of Thalaivetti Muniyappan in Salem was actually a statue of the Buddha. The court has ordered the land of the temple to be handed over to the Archaeology department and for Hindu rituals to cease. In an equal world, accepting the challenge to the Places of Worship Act would throw up a legal tsunami.

A place may change hands between multiple faiths in its history – for instance, in the Daulatbad fort, a Jain temple was converted to a Muslim mosque and then converted to a Bharat Mata temple. Should it go back to the Jains or the Muslims?

Religious desecration as conquest, is, however, not the only reason why religious places may lose their original character. Populations die out in a particular place, shrines acquire new worshippers, and of course, there are so many glorious examples in this country of syncretism where people of diverse faiths worship together as in the Sufi dargahs of Delhi.

Historical and religious structures are inevitably layered upon each other, and a petition which seeks to privilege one kind of restoration of a place of worship over others needs to be thrown out at the very outset as violative of Article 14.

When the state demolishes Hindu temples, does that make it more legitimate?

Those Hindus who care only when Muslims demolish their temples rather than when the government does so, in the name of development, road widening, removing encroachments, etc. actually care less about their temples and their religion than about getting the better of Muslims. The best example perhaps is the destruction of Shoolpaneshwar and other old Shiva temples along the Narmada which is itself sacred. Why do the cracks in the Badrinath temple and the sinking of Joshimath due to reckless building in the hills not excite the same emotions both among ardent Hindutva adherents and the BJP governments in power, as does demolishing a mosque in order to build a grand new temple there?

When it comes to Muslim shrines, however, a BJP-run government is almost synonymous with the Hindutva vigilante brigades. The Ahmedabad Municipal Corporation building a road over Vali Guajrati’s tomb in Ahmedabad was really a continuation of the 2002 pogroms, in which mosques and dargahs were destroyed. In Delhi, the Union Housing and Urban Affairs Ministry’s takeover of 123 properties belonging to the Delhi Waqf Board and the demolition of some of them in the name of road widening is clearly malafide.

This urban beautification logic which is applied to century-old mosques does not seem to matter when it comes to the hundreds of ‘Pracheen Shiv Mandirs’ and “Pracheen Hanuman Mandirs’ which dot our cities in North India. Before my eyes, a Pracheen Shiv Mandir came up in my residential area during the COVID-19 pandemic, next to a board which said ‘Government land, do not trespass.’ The police sat outside it while it was being constructed and held COVID-19 vaccine camps there. Incidentally, the entire area used to be a Shia graveyard which was transformed into a Hindu colony after Partition.

Upadhyay claims that the Places of Worship Bill cuts off legal redress. This is no more than any statute of limitations. Instead, one might argue that the Places of Worship Act enables legal redress for people whose shrines have been forcibly taken over by more powerful forces, which in India today, can only be the RSS followers.

Adivasi places of worship

Of all the communities that need to invoke the Places of Worship Act and demand the restoration of their shrines, it is the Adivasis. As one of India’s most vulnerable and constitutionally protected groups, it is they who should be the first charge on the legal system. Unfortunately, however, their beliefs are totally discounted.

Take, for instance, the hill in Giridih where Adivasis worship as Marang Buru and Jains worship as the Parasnath hill. The BJP government wanted to convert it into a tourist spot, and backed off only under Jain protest. Will the Supreme Court hand the Sabrimalai temple back to the Mala Araya tribal community who were displaced from it by Brahmin priests? In the last three decades alone, I have seen how several Adivasi and OBC priests have been displaced from small shrines in Bastar, and the space taken over by Brahmins. By traditional accounts, Lord Jagannath of Puri was stolen from the Sabaras.

But this kind of religious appropriation is just one of the many attacks that are taking place on Adivasi religious sites. Sacred hills such as Niyamgiri (Odisha), Surjagadh (Maharashtra), Raoghat (Chhattisgarh) are being taken over for mining, and the believers who worshipped at these shrines are being attacked for protesting.

In the Ayodhya judgment, the court emphasised the practice of worship in determining who should have title to the land. When it comes to Adivasi sacred hills, there is evidence of continued practice of worship over several generations, with people coming from far away, even neighbouring states. Even when closed off by mining authorities, as in the Bailadilla hills, Adivasis seek permission from mining authorities to go and worship, because it would be inconceivable to abandon that sacred space. As of 1947, they were places of worship and should be recognised as such, even if a postcolonial government wants to enact colonial practices, treating them as terra nullius and available for mining.

Mutual accords

The Places of Worship Act makes an exception for places of worship whose conversion is settled by mutual acquiescence before the commencement of the Act. Perhaps the lawmakers recognised that mutual acquiescence in a communal vitiated atmosphere where one side was dominant was meaningless. The dargah at Pavagadh which Uma Bharti claimed in the parliamentary debates on the Place of Worship Bill, hurt her sentiments, has now been removed by “mutual consent”, enabling Prime Minister Narendra Modi to unfurl a triumphal flag atop the temple spire. One can only presume that this was much like the “compros” that enabled Muslim villagers to return to their villages after the 2002 pogroms.

But perhaps all is not lost in this country. In the last few years, the Sikhs of Punjab have restored mosques which were abandoned after Muslims migrated to Pakistan. It is this model that we need to emulate – one that seeks to promote communal harmony in the present – rather than the revanchist and illiterate model promoted by the RSS. But for this, the courts must respect the faith of all Indians, and above all, respect the constitution in which all Indians have faith.

(Nandini Sundar is a Delhi based sociologist. Courtesy: The Wire.)