Why Justice Lokur Feels the Supreme Court Should Review its Article 370 Judgment

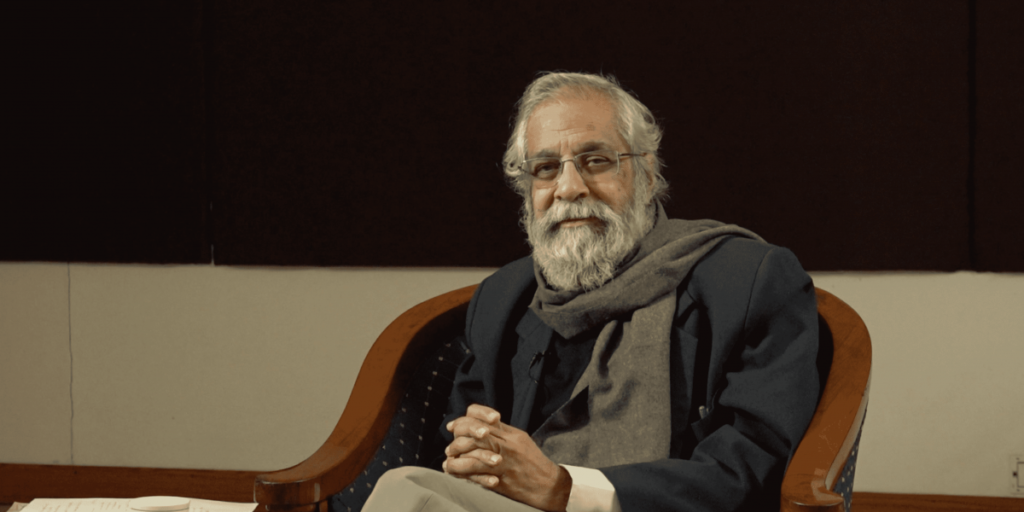

[One of the most highly regarded former judges of the Supreme Court, Justice Madan Lokur, recently told Karan Thapar that the Supreme Court has erred and cannot be proud of its Kashmir judgement, in which it upheld the Union government’s move to read down Article 370.

Justice Lokur also described the Supreme Court judgement as complex and complicated adding it’s at least 200 pages too long.]

● ● ●

Karan Thapar: Hello and welcome to a special interview for ‘The Wire’. There’s no doubt the Supreme Court’s Kashmir judgments of Monday, the 11th, are complicated and for some people very difficult to understand. They are, of course, widely anticipated and long expected. But that makes understanding them even more important. So joining me today to help explain the judgments is one of India’s foremost senior judges of the Supreme Court, the highly regarded and well-regarded Justice Madan Lokur. Will help us both understand the judgments as well as their implications and indeed their complications.

Justice Lokur, let me start with a simple general question. I’ll come to the details after that. How do you view, in an overall sense, the Kashmir judgments that were announced on Monday, the 11th? Are you impressed by the judicial arguments they contain, or do you have reservations about some of the reasoning and its implications?

Madan Lokur: Yes, well, thank you, Karan. There are two or three things. One is that the case wasn’t as complicated as the judgment makes it out to be. I think that maybe 200 or maybe 250 pages of the judgment were not necessary, unless I’ve missed something. I’ve not been able to connect the dots or something. But I think maybe 200 or 250 judgments could be straight away taken out. Now, in a judgment, I would expect that when you are referring to something which is not readily available, the constitution of India is readily available, a law enacted by Parliament is readily available. But when you’re talking about a constitutional order which has been passed with reference to Jammu and Kashmir, that’s not readily available. I mean, you have to go through the internet and get that, and some facts pertaining to the constitutional order, they were not a part of the judgment. So then it becomes very difficult when you’re reading the judgment, and then you want to refer to something. You have to go to your computer and try and look at the constitutional order and see what it says. So these are things which make it difficult to go through the judgment. Now, as far as the submissions are concerned and the reasoning is concerned, like I said, if you take out 200 or 250 pages, then it doesn’t become so complicated, then the issues get narrowed down. In fact, they were narrowed down at some part of the judgment. And if you look at it from that point of view, well, the reasoning you could disagree with is right. You, I mean, in any case, given the same facts, judges disagree.

KT: So what you’re saying in terms of your overall view is a) it could have been pages shorter, which would have made it easier to understand, b) it could have referred to many of the things that it talks about rather than requiring you to have to cross-reference them from computers. So it’s neither easily written nor easy to fully follow.

ML: Yes. In fact, it took me a long time to understand the judgment because it was so complicated. Then you keep going back and forth, forth and back.

KT: So they’ve made it deliberately difficult to follow.

ML: I don’t know whether they made it deliberately difficult, but it is difficult to follow.

KT: Let’s then, with that as the background, come to the details. And because they’re complicated, as you say, I’ll take the question slowly. More importantly, with your permission, I’ll read the questions because I think in this instance, at least terminology is important. I should be using the right words rather than just any word that fits in. Now, first of all, you’ve discovered that “although the petitioners challenged the dissolution of the assembly and the imposition of Governor’s Rule and the Supreme Court judgment acknowledges that both were challenged, the court actually failed to discuss the challenge and therefore to suspend it. The petitioners had argued that an alternate government was viable and therefore the dissolution and Governor’s rule were unconstitutional. Had the Supreme Court agreed with this challenge, everything that followed the dissolution and Governor’s rule, such as President’s rule, such as abrogation of article, such as the reorganization of the state, all of that would have been invalid.” So let me start by asking, was this a lapse on the Supreme Court’s part not to directly challenge, not to directly tackle this challenge? And if it was a lapse, how serious a lapse was it?

ML: The Supreme Court notes in paragraph 19, I think, that the proclamation issued by the governor was under challenge. And I think in the same paragraph or maybe a paragraph or two later, the Supreme Court notes that “the proclamation issued by the president was also under challenge.” Two proclamations were both under challenge. The Supreme Court doesn’t say anything about the dissolution of the assembly. Right, so this is a fact which has not come on record. But I assume that the assembly was dissolved at some point in time because they’ve given a direction that elections should be held. So I’m assuming that the assembly was dissolved at some point in time. Now, so far as the proclamation issued by the governor is concerned, the Supreme Court didn’t go into it. Now that was the first step, so to speak. The first thing that happened was after the resignation of the chief minister, the judgment records that on the next day the governor issued the proclamation.

KT: Dissolving the assembly?

ML: I don’t know whether it was dissolving the assembly, but imposing Governor’s rule. Okay, so once Governor’s rule was imposed, the argument also of the petitioners was that listen, we’d been telling the governor even after the resignation that we can form the government. The coalition partner may have backed out, but we can still form the government. Now that opportunity does not seem to have been given by the governor, and the next day Governor’s rule was imposed. Now the argument was that there was no material before you to impose Governor’s rule. Why should you impose Governor’s rule when we can tell you that we are in a position to form the government? Give us a chance to form the government. The Supreme Court didn’t look into that, unfortunately. Now with regard to what the Supreme Court said was that subsequent events were challenged. All subsequent events were challenged, but that doesn’t mean that the challenge to the proclamation was given up. Then with regard to the presidential proclamations, the Supreme Court says that we’re not looking into it, and they give two or three reasons.

KT: I’ll come to the presidential proclamations in a moment’s time. Let’s first focus on the Supreme Court’s failure to look into the governor’s proclamation declaring Governor’s rule. As you pointed out, Mehbooba Mufti, in particular, said the declaration of Governor’s rule is improper and unconstitutional because an alternate government can be formed. Give me time; I’ll form it. She wasn’t given time, and therefore, the governor was imposed at a stage when an alternative could have been brought into being in the form of government. Therefore, it was wrong. And what you’re saying, if I understand correctly, is if the Supreme Court had looked into the declaration of Governor’s rule, it could have concluded Governor’s rule was prematurely and wrongly declared. And if that’s the case, everything that follows after the Governor’s rule will become invalid. Therefore, abrogation of 370 would become invalid, and therefore, reorganization of the states would become invalid. Yeah, so failure to look into Governor’s rule meant that you could have checked the process there and then, but they didn’t.

ML: Yes, the next day, that’s what turns out. Governor’s rule was imposed, okay. This was, if I remember correctly, sometime on June 18 or 19 or something. Now the notifications that were under challenge to the constitutional orders were issued on the 5th of August, so between the 18th or 19th of June and the 5th of August, there was time in theory for somebody to form the government.

KT: That was the key of the challenge, and by not looking at that challenge, the Supreme Court failed to take a step that might have led to the conclusion the abrogation was wrong, the reorganization was wrong. Because if a new government could be formed, there’d be no opportunity for any of these things.

ML: Yes, yes.

KT: So we’re agreed this is a very serious lapse on the Supreme Court’s part.

ML: Yes.

KT: Let’s then come to the second important thing. This is the Court’s decision to uphold what is popularly called the “abrogation of Article 370”. Now, this is particularly complicated, so I’ll go through it very carefully with you. On the one hand, the majority judgment written by Chief Justice Chandra says that “the critical part of constitutional Order 272, which reads down Article 370’s ultra vires because it wrongly used Article 367 to interpret the Constituent Assembly as a legislative assembly. Yeah, and since the process that the government had used to abrogate 370 was precisely this process, the court should have actually struck down the abrogation. But it didn’t. What the court instead said was that because Article 370 can be read down by use of Clause 3, therefore it upheld what the government did. And in effect, what that means is that the Court ruled that what the government did was wrongly done but if it had been done differently, it would have been correct. And therefore, it gave the government the effective benefit of the doubt. Now, to my mind, that’s a convoluted sort of logic. How do you view it?

ML: Yeah, the constitutional Order 272, right? It had three things if you don’t mind if I can just go through it. It said, first of all, that the constitution of India is applied in full to the state of Jammu and Kashmir like it applies in full to every other state in the country. Second, it said that the expression Constituent Assembly in Clause 3 of Section 370 should be read as legislative assembly because of an amendment made in Article 367, which deals with the interpretation of the constitution. The third thing which the constitutional Order 272 says is that all past constitutional orders are obliterated or revoked or abrogated or whatever. Now, the Supreme Court said that you can’t read the Constituent Assembly to mean legislative assembly. Why can’t you do that? Because you are then amending Clause 3 of Section 37 of Article 370. You cannot amend Clause 3 or even Article 370 without the consent of the state government. So, therefore, you can’t read the Constituent Assembly to mean legislative assembly. But they said that the constitution of India can be applied in full to the state of Jammu and Kashmir. Now, I don’t think that’s correct because if that was correct, then why make this amendment.

KT: Absolutely, and if the amendment is wrong, yeah, and the amendment is the basis upon which the government is trying to amend 370, yeah, then the attempt to amend falls by the wayside.

ML: Yes, I mean Article 379 could not have been amended, let’s be clear about it. But there, I think the Supreme Court falters, they’ve come to some conclusions which I’m unable to understand how they’ve come to. For example, they say that it’s all right if the constitution of India is applied to the state of Jammu and Kashmir. Now, if it was so simple, it could have been done without all this rigmarole.

KT: Absolutely, and to my mind, and I’m not a layman, but the simple thing is the procedure that the government used to amend 370 was to reinterpret the Constituent Assembly, to make it a legislative assembly. Yeah, the second the Supreme Court says that’s ultra vires, then the procedure the government has used becomes ultra vires, yeah, and therefore it follows that you must strike down what the government has done, right? But they didn’t. Instead, what they did was to say you may have done what you wanted to do the wrong way, but there is another way of doing it, yeah, which is to use Clause 3. If you used Clause 3, it would have been okay. They overlooked the fact that the government didn’t use Clause 3 but gave them in a bizarre way the benefit of the doubt, said had you used it to be okay. Therefore, we’ll recognize what you’ve done even if you didn’t do it the right way, but there was another way of doing it that was the right way, and we’ll accept that as the right way.

ML: Yeah, I’m not sure if they went to that extent because Clause 3 could not have been amended, alright, because they said that you can’t amend Clause 3.

KT: But there, forgive me interrupting you, sir. What they said, if I understand them correctly, is that Clause 3 requires a recommendation from the state, but because the constituent assembly no longer exists, all that is now removed is the requirement for the recommendation. That doesn’t say stop the president still acting. Yeah, the president, they say, can still act even if he doesn’t get the recommendation. All that’s obliterated is that the recommendation can’t come, so that was another slight of hand that allowed them to use Clause 3.

ML: Say you can use Clause 3, yes, but they don’t say all this explicitly. They imply it by saying that, well, under this 272 constitutional order, you could put the constitution of India over there. Right now, if you could put the constitution of India over there, there was no need for you to amend 370 Clause because it was already over there. It was already over there, right? Then at another place, when towards the conclusion, I think it’s in paragraph 400 or something, they say that the article could have been abrogated or could have been revoked. Now, if it could have been revoked or abrogated or whatever expression they used, then they should have just done it.

KT: Rather than have to go through the wrong interpretation route, yeah. And this is the funny thing when you find that the route the government has taken, which is to attempt to re-interpret a phrase constituent assembly to mean legislative assembly, and you come to the conclusion that is ultra vires because that’s the root the government’s taken. The logical thing to do is to say sorry, what you’ve done is wrong.

ML: You’re right, but they didn’t say that.

KT: No, and this is the bizarre bit. Instead, what they said was that there’s another way of doing it via Clause 3 towards requires a recommendation from the constituent assembly, but they’ve argued, and I think the Chief Justice in his judgment argues that because the constituent assembly doesn’t exist, it can’t give a recommendation that invalidates the recommendation. But it doesn’t invalidate the power of the president to act without any recommendation.

ML: Yes, now, but for that, that’s bizarre. But for that, they don’t use Article 370 Clause 3; they use Article 370 Clause 1 to say the same thing, to say the same thing.

KT: But then don’t we come to two strange conclusions. First of all, it seems as if they’re putting arguments in the government’s mouth and deeming their arguments to be correct. And this is Kapil Sibal in his tweet very famously said, I’m quoting his tweet, he says, “the Court’s verdict had little to do with the government’s own understanding of Article 370. The government’s understanding hinged upon a reinterpretation of the constituent assembly.” The Court’s verdict didn’t hinge upon that at all; it found the reinterpretation of malafide and ultra vires. They said the route is 371. Yeah, so in other words, they suggested to the government what the government could do even though the government hadn’t done it. And then presumed that if they had done it, it would be okay, therefore what the government’s done is okay.

ML: Yes, I’ll put it slightly differently. The case of the government was dependent upon the Constituent Assembly becoming the Legislative Assembly. Gee, that did not happen. Now if that does not happen, then the case falls to the ground. What the government also seems to have done or what the court seems to have done, I don’t know if the government argued that, they said that the powers of the State Assembly are with the governor. The powers of the governor are with the president. The president says, or the Parliament says, and the President says that, all right, you delete Article 370. So we delete Article 370. That’s what the court says. Now I’m not sure whether that was argued because it could not have been argued. I would put it slightly differently. I would say that it could not have been argued because the case hinged upon the Constituent Assembly becoming the Legislative Assembly.

KT: That’s right.

ML: There was, as far as I know, like I said it’s such a complicated judgment as far as I know, and the alternative argument was not advanced.

KT: And yet the Supreme Court has behaved as if it was.

ML: Yes, yes.

KT: And this is what I mean when I say the Supreme Court has effectively put words in the mouths of the government because what the Supreme Court claims is the route you could do it by is not the route the government chose to do it by. Yeah, and the route the government chose to do it by reinterpreting Constituent Assembly to mean Legislative Assembly they struck down. Yeah, so in effect what they’re saying to the government is what you did, you did the wrong way and we ought really to be striking it down, but we won’t because there’s another way of doing it which you didn’t choose but had you chosen it would have been correct. Yeah, and we’ll give you the benefit of the doubt. Yeah, and that’s convoluted logic to me.

ML: Yes, it is.

KT: And it seems to me that not only is it convoluted, but the Supreme Court has sort of tied itself in because instead of adjudicating what the government’s done, they’re virtually advocating to the government what it should have done.

ML: Yeah, they’ve not put these words crudely is that, yeah, but I mean they said this, this is how it is.

KT: So as a former very highly regarded judge of the Supreme Court, you’re rather unhappy with the way the Supreme Court has handled this issue of abrogation.

ML: Yes, yes, I am unhappy because I’m not sure how they’ve come to certain conclusions and certain conclusions they have, like this constitution of India can be applied in full state, how have they come to that conclusion?

KT: They sort of asserted it, yeah, it’s like an assertion. They’ve also come to the conclusion, I think, like in paragraph 400 or something or 420 or something that Article 370 could be abrogated. How did they come to that conclusion? Again, they’ve asserted it.

ML: Yeah, yeah.

KT: So just to sum up this bit of the conversation, you’re unhappy with the way the Supreme Court has handled the abrogation of Article 370? And what they’ve done is they’ve provided grounds for actually striking down the abrogation because they say that the interpretation of Constituent Assembly as Legislative Assembly is ultra vires. But they haven’t actually taken that to its conclusion. Instead, they found an alternate method which the government didn’t deploy but nonetheless they said that if you had deployed it would be correct, therefore we give you the benefit of the doubt. And therefore it’s a very strange case where actually the logic of their position should have struck down the abrogation, but they’ve ended up doing exactly the opposite because they’ve posited there’s another way of doing it which they’ve simply asserted.

ML: Yes. And like you said, they simply asserted it without giving reasons which I’m satisfied about.

KT: So this is not just a position or unhappy with but this is a bad judgment.

ML: I wouldn’t say it’s a bad judgment, but yeah, I’m not satisfied with the reasoning given.

KT: Let me put it this way: it’s neither clear nor convincing.

ML: Yes, yes, you could say that, yeah.

KT: Let’s now come to a second part of what the Supreme Court had to handle in its refusal to determine whether the reorganization of the state was permissible under Article 3, in layman’s language whether the government had the power to demote Jammu and Kashmir from a state to a union territory. Now here it seems to me the court has relied on three separate arguments. The first argument, and I quote from the judgment, is “we do not believe that the court ought to sit in appeal over every decision taken by the president during the imposition of Article 356 because if every action taken by the president and Parliament on behalf of the state was open to challenge, this would effectively bring to the court every person who disagreed with an action taken during president’s rule.” Do you accept that as a legitimate reason for not determining whether something the government has done, reorganization in this case, is constitutional?

ML: Yeah, the passage that you have read, sorry I don’t know in what context they’re saying it because what was the argument advanced by the petitioners.

KT: They don’t say.

ML: They don’t say that. Now to find out what is the argument, you’ll have to go through, it’ll take minutes to figure out what was the argument. So I really don’t know in what context it said that. But normally, forget about reorganization or any such thing, any decision taken by the government, if it is wrong, it can be challenged, right? Now I don’t see any reason why if a decision is correct, somebody would want to go to court and say that I think it is wrong even though it is right. So I would say that this kind of a sweeping statement that has been made, I’m not sure about the context in which it has said it has been said, and I’m not sure whether the Supreme Court was trying to lay down a law, that listen just because president’s rule is been imposed, therefore you cannot challenge any decision.

KT: But it’s even worse, isn’t it, Justice Lokur, that deferring or actually not taking up a duty that is incumbent on the court.

ML: Yes.

KT: It is the Supreme Court’s duty to sit in appeal over every decision, if that decision is challenged. Correct, they’re saying exactly the opposite; they’re saying it’s not our duty to sit in appeal over every decision, otherwise we’ll be sitting in appeal every time someone comes to challenge something. But if everyone comes to challenge something every time, it’s your duty to sit in appeal.

ML: Yeah, yeah, I think it was an error, if I may use that expression, by not deciding the reorganization aspect, that is the break-up of the state of Jammu and Kashmir into two union territories. That was an issue that was directly before the Supreme Court.

KT: Which they decided.

ML: Which they did not decide. But they said that it will be decided in an appropriate case whether this can be done. Now, this was the most appropriate case as far as I can understand.

KT: Yes, absolutely.

ML: Now, if it was the most appropriate case or if it was an appropriate case where this question had arisen, and in fact, the Supreme Court did say that this question arises, they should have answered it.

KT: They seem to have, if you read their judgment, produced a second reason for not determining whether the reorganization of Jammu and Kashmir was done constitutionally or not. Here they’re referring specifically to the requirement under Article 3 for a recommendation from the state legislature, and they say it’s not binding on Parliament. And therefore, they say because it’s not binding on Parliament, just because it’s not available doesn’t stop Parliament acting. Now it may not be binding, and I agree, but it’s a stipulation specifically mentioned in the constitution. And even though the constitution says it’s not binding, the constitution does say that’s a requirement of the process you have to go through. So can you circumvent a stipulated process in the constitution just because it’s not binding?

ML: No, again, this is where there’s a problem. Now, if the recommendation of the legislative assembly is necessary, right?

KT: Which it is.

ML: Which it is, yeah, I’m assuming that, and the governor is acting on behalf of the president, and the president can take over the functions of the legislative assembly, the president could have made a recommendation. Okay, then you would not have to circumvent Article. Now, for the purposes of, they say that there’s a recommendation from the president. Now, if there’s a recommendation from the president for Article 370, the president could have given a recommendation for the purpose of Article 3 as well, which he didn’t, which apparently he didn’t.

KT: Okay, so here, by the way, their logic is at odds with each other. Yeah, what they say in one case, they don’t say in the other.

ML: Correct. Now, if that was so, if the president did not give the recommendation as far as Article 3 is concerned, then you decide it and say that, well, there’s no recommendation from the president, and so, therefore, we do not agree, although.

KT: Here, I think they’ve taken the opposite route. They say there’s no recommendation from the State Assembly because the State Assembly no longer exists, but they say the State Assembly recommendation is not binding because it’s not binding. It’s, therefore, not necessary; the president can act on his own. But the constitution specifically stipulates it’s necessary. Yes, and my question is a very simple one. Just because it’s not binding doesn’t mean you can circumvent a constitutional stipulation because the constitution may well have hoped that even though the recommendation is not binding, it still could change the thinking of Parliament. That opportunity to change the thinking of Parliament was denied by saying we don’t need the recommendation; we’ll do without it.

ML: Yeah, but that makes it easier for them to decide.

KT: Now, so once again, and this is another area where you’re unhappy with what they’ve done.

ML: Yeah, yeah. According to me, they should have decided the reorganization question; it was the most appropriate case, and they should have decided it.

KT: Absolutely, not deciding it is irresponsible, actually, well-ordered election of duty.

ML: Well, you could say that it’s wrong; they should have done it. I don’t want to use this.

KT: I agree, but it was also so incumbent on them to do it; yeah, it was incumbent, so it was a duty that they didn’t fulfil.

ML: Yes, yes, and the reason that they’ve given that let’s wait for a more appropriate case I don’t think is not a good enough reason.

KT: It’s a bizarre reason. What better case can there be than this, yeah. And the argument that the recommendation is not binding, therefore we can do without the state assembly’s recommendation is a misunderstanding of the constitution. It’s disregarding what the constitution has stipulated.

ML: Yeah, because this sort of a situation may not arise in any other case.

KT: Absolutely. Now the third reason, and here I’m reading between the lines for not determining whether the reorganization of the Jammu and Kashmir assembly is constitutional, lies in a statement that they made. The court said restoration of statehood shall take place at the earliest as soon as possible. And because they believe they’ve given that advice, therefore, there was no need, I assume, to look into the matter because anyway, it will happen, so why look into it now. But that’s a bizarre way of approaching a problem, yeah.

ML: It would mean that Parliament would have to pass a law. Right now, I don’t think any lawyer can give a statement to the court on behalf of Parliament. All right, so that statement should not have been accepted.

KT: And also, sir, this claim that it should happen at the earliest as soon as possible is vague and undefined; as soon as possible and at the earliest could be 5 days, 5 months, 5 years.

ML: Yeah, frankly, I don’t think that statement should have been accepted.

KT: So once again, just as you were unhappy with the way the Supreme Court handled the abrogation of 370, you’re equally unhappy or maybe even more so in the way they failed to look into the reorganization of the state.

ML: Yeah, I’m repeating it; this is, they should have looked into it. Where is the question of saying that you pass a law and grant statehood? You got a problem before you.

KT: Here your unhappiness is even greater, I sense.

ML: Yes, you could say so, yes.

KT: Now, one consequence of the Supreme Court refusing to determine whether the reorganization of Jammu and Kashmir was constitutional is that this process of reorganizing, this method of doing it, can now be used again and again because a precedent has been set. Tomorrow or the day after, if the government were to choose, say, in the case of opposition rule states like Bengal, Tamil Nadu, Kerala, to first impose president’s rule, then transfer the powers of the assembly to Parliament, and if Parliament decides to either abolish the state altogether or reduce it to Union territory status, what the president has said.

ML: Theoretically, yes.

KT: And how come the Supreme Court didn’t realize that through their lapse, allowing a precedent to be set that can endanger Indian federalism?

ML: Yes, you’re right. It’s possible that Parliament does this. Alright, take any particular state and they say we’re converting that state into two union territories, and it’s challenged before the Supreme Court, and the Supreme Court says, well, there’s no recommendation of the state legislature, and even if there is, it’s not binding; it’s not binding upon us. So, therefore, the division of this particular state into two union territories is okay, and we record the statement of the solicitor general or the Attorney General that at some point in time statehood will be given back to that particular state. Right, and the question of whether it is constitutionally valid or not, we will decide it in another appropriate case. So you wait for a third state to be divided; when the third state is divided, then you say, well, we’ll wait for the fourth state.

KT: In other words, they are now hoisted by their own petard.

ML: The logic they’ve used once, they might be required to use again and again and again. Yeah, that’s why, that’s why I think they should have decided it, right or wrong.

KT: Do you think they realize the importance of what they failed to do?

ML: They should have; they should have, ’cause it stares them in the face, yeah, yeah, they should have.

KT: And there was endless commentary in the papers for three or four years that what has happened to Jammu and Kashmir, if it is upheld, sets a precedent for doing this in any other state.

ML: Yeah, yeah.

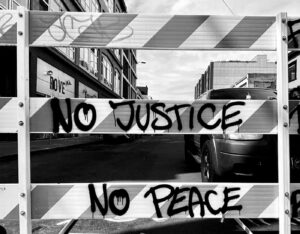

KT: In fact, the second consequence is precisely what I’m talking about. It was a point made by Alok Prasanna Kumar writing the Indian Express on the 13th of this month. He points out that federalism has been accepted by the Supreme Court itself as part of the basic structure of the constitution. That means federalism cannot be amended, but the power to reorganize a state has now been accepted by the Supreme Court as a parliamentary power. Yeah, so don’t we here have at least incipiently a clash between the power of parliament on the one hand and the sanctity of the basic structure of the constitution on the other.

ML: Yeah, there is a problem. In the past, Andhra Pradesh, for example, or Bihar and Jharkhand or Madhya Pradesh and Chhattisgarh, were done on the basis of recommendations made by the Legislative Assembly. Okay, so that’s fine, but now what the judgment says is that that’s not even necessary. Quite right, okay, so if it’s not necessary, then what happens to federalism?

KT: A nasty government, and maybe the word nasty is a bit editorializing, but a determined government can say we don’t need the recommendation of the state; we’re determined to teach the government in Bengal, Tamil Nadu, and Kerala a lesson. We will declare the president’s rule. We will then use the power of parliament, which has assumed the power of the assembly, to divide the state into two and reduce both hubs to Union territory status. And there’s nothing anyone can do because the Supreme Court has set a precedent, yeah, which is why Mr. Alok Kumar Prasanna says, “Federalism has been effectively threatened by what the Supreme Court has decided in this case.”

ML: Yeah, yeah.

KT: You agree?

ML: Yeah, yeah, except that the Supreme Court will have to decide it. I mean if they keep shirking the…

KT: They shook it once; they could shirk it again and again and again.

ML: Yeah, correct. That’s why I keep saying that they should have decided this.

KT: And presumably if they’re going to decide it, they now need a seven-judge bench to decide it.

ML: Not necessary because they’ve said that it can be decided in an appropriate case. So five judges can say, well, this is an appropriate case so we are deciding it.

KT: Except they have to first agree that the case is appropriate. I mean the most appropriate case is the one they consider not to be appropriate; who knows what they consider to be appropriate.

ML: Yes, absolutely, yeah.

KT: The Hindu makes a further point, and I want to raise that with you. They made it in the leader that they wrote on the 12th. They say, and I’m quoting, “The Supreme Court’s judgment suggests the unconsciously questionable conclusion that Parliament while a state is under president’s rule can do any act legislative or otherwise even with irreversible consequences on behalf of the state legislature.” And then the leader continues, “This may have grave implications for the rights of states; it undermines federalism and Democratic processes to a frightening degree.” As I read that, it seems to me that they’ve effectively, the Supreme Court has effectively opened a Pandora’s box of problems.

ML: Yeah, if you think about it, what are the kinds of irreversible decisions that can be taken? One irreversible decision that can be taken is the dissolution of the assembly, okay, which happens. Another irreversible decision that can be taken is the breakup of the state, alright. I can’t think of a third irreversible decision; I mean except hanging somebody or something.

KT: Keep the state intact but demote it.

ML: Yeah, yeah, what has happened in Jammu and Kashmir and the third, I mean if you say hanging somebody irreversible, yes. I can’t think of any other thing which is irreversible. So, therefore, what The Hindu seems to be saying, in my view, is with reference to what happened in Jammu and Kashmir. Okay, so you have created an irreversible situation where you have broken up the state into two union territories; you can’t put them back. Right, why? Because the Supreme Court says that this is not an appropriate case. Now the question is could the Supreme Court have said that well this is unconstitutional. Of course, the Supreme Court could have said that. And if it had said that well, the reorganization goes, and it comes back to statehood.

KT: And just to go back to what we discussed earlier, the Supreme Court actually had a good reason for saying abrogation is unconstitutional because they said interpreting constituent assembly is legislative assembly, which is the mechanism the government used is ultra vires. So if they followed their own logic, they should have said your act of abrogation is unconstitutional; you’ve used the wrong way of doing it. Whether there’s another better way of doing it is now for the government to discover later on, not for the Supreme Court to advocate it to the government in a sense.

ML: Yeah, the Supreme Court has not advocated it.

KT: I mean they have; they found a way of saying if you’ve done this we have accepted it.

ML: Yeah, not that we would have accepted it, we are accepting it.

KT: We are accepting it, which is even worse.

ML: Yes, yeah.

KT: As I said, what you did you did the wrong way, but there was another way of doing it that would be right, and we’d accept it on the grounds that there is a way of doing it that’s right. But that’s not the way the government did it.

ML: That’s not the way the government did it; that’s not, I think, the way the government intended to do it. And I think the reasoning of the Supreme Court is incorrect.

KT: This is why I say it’s a bit like putting arguments in the government’s mouth because it’s not the way the government intended to do it, but the Supreme Court saying speak this way, and you’re saying the right thing. So right at the end of this interview, let me ask you after our discussion what is your final opinion of the Supreme Court both in terms of the handling of article 370 and its abrogation and in terms of reorganization of Jammu and Kashmir? You began by saying this is a complicated judgment. It’s probably 200 pages too long, right, and it’s often inconsistent. But now that we’ve been through it in somewhat more detail, what is your final opinion of this judgment?

ML: Well, I think the Supreme Court should review it. I’m pretty sure that some of the petitioners will apply for a review. And the Supreme Court should actually look into it. And what they have done, like I said, I’m not satisfied with the reasoning.

KT: Is this a low moment for the Supreme Court in terms of judgments they’ve delivered on critical issues?

ML: I wouldn’t say it’s a low moment, but it’s not a moment that I would be proud of.

KT: The Supreme Court should not be proud of its Kashmir judgments.

ML: Yeah, or at least I, as a citizen of India, I’m not proud of it.

KT: And that also means that the Supreme Court, you believe, has erred grievously.

ML: It has erred. Grievous is a matter of opinion, but it’s heard, definitely, yeah.

KT: So this is not a judgment the Supreme Court should be proud of; it has erred; it should review it.

ML: Yeah, yeah.

KT: All three are correct?

ML: Yeah, yeah.

KT: Justice Lokur, thank you very much for taking us through and for making it so simple for laymen to understand what is actually a very complicated complex. And I would add confusing judgment, at times, where quite often what the Supreme Court does conflicts with what the Supreme Court’s logic suggests it should do. Article 370 being a prime example. I thank you for having made it so much easier for people to understand.

ML: Thank you, thank you.

(Karan Thapar is a well known journalist, television commentator and interviewer. Courtesy: The Wire.)