Research Unit for Political Economy

(Note: The article has been edited by us for reasons of space. The full article is available on RUPE website.)

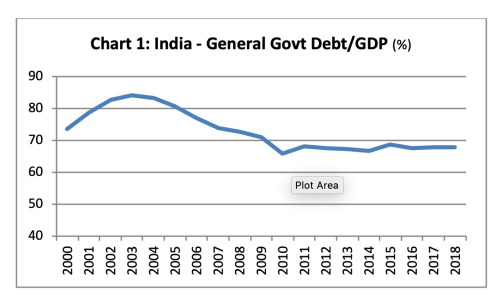

For three decades now, the IMF, and now the foreign credit ratings agencies, have warned the Indian government about the size of its ‘fiscal deficit’ (i.e., the sum of all borrowing by the Government in a given year), and called for Government spending to be reduced. They continue to raise the alarm in the midst of the present grave crisis. Why do foreign investors in India oppose an expansion of Government spending?

1. The Real Reasons for Foreign Investors’ Opposition

A regime of ‘austerity’ in government spending, while ruinous for a particular economy, can yield rich returns for foreign investors. The following are not distinct points, but are different aspects of a single theme.

(i) When a government refuses to spend and revive demand, economic growth depends entirely on the desire of private sector investors to invest. In order to stimulate the private corporate sector to do so, the rulers provide all sorts of inducements and subsidies at the cost of the people. During a crisis, the bounties get even more extravagant. Such gifts to the private corporate sector benefit foreign investors, whether through their local subsidiaries, or their tie-ups with local firms, or through their purchase of shares in local firms.

(ii) Similarly, when governments are under pressure to reduce their fiscal deficits, they carry out ‘reforms’ which create opportunities for private profit-making, albeit at a cost to the public. For example, when governments cut back on infrastructural invesment, as well as public health services, education, agricultural extension services, etc, they correspondingly expand opportunities for private infrastructure firms, private corporate healthcare, private schools and universities, corporate penetration of agriculture, and so on. In pursuit of this aim, India for some years became the world’s leader in ‘public-private partnerships’. These have resulted in massive fiascos and scandals, at a staggering loss to the public, but they remain the Government’s preferred method of performing its functions.

(iii) Further, under the banner of reducing the fiscal deficit, governments sell shares in profitable public sector firms, or sell off the firms outright. Since governments are selling these assets under pressure of time and budgetary targets, they sell them in ‘fire sales’, i.e., at distress prices. These create bonanzas for cash-rich foreign investors.

We have just seen a living demonstration of all the above three points, with the Finance Minister’s marathon presentation of the Government’s economic package ‘for Covid-19’. The package contains government spending worth hardly 1 per cent of GDP; but under the cover of addressing the crisis, it brings in a staggering list of privatisations, deregulations, and other gifts to the corporate sector and foreign investors. As we mentioned in the earlier instalment of this article, when foreign investors oppose an expansion of Government expenditure, the Government banks solely on stimulating the ‘animal spirits’ of capitalists to invest, by providing them incentives and concessions of all types. This the present Government has again turned to with gusto.

(iv) Finally, slashing government spending depresses domestic demand. That depresses the prices of assets and labour power in the country. It may also lead to domestic firms making losses, and defaulting on their loans. Foreign investors can then buy up various assets, including debt-stressed Indian private firms, at distress prices. (In fact, a section of the large corporate sector in India is itself worried about this, and has been asking the Government to increase its spending and boost demand.)

In times of worldwide crisis, governments of the developed world expand their spending dramatically, even as governments of underdeveloped countries like India (or even relatively weaker capitalist countries like Greece) put government spending on a starvation diet. In this situation, corporations of the developed world are even better equipped to ‘raid’ underdeveloped countries for their distressed assets.

What this means is that, even though the crisis reduces ‘regular’ profits for international capital, it is also an opportunity for it to make extraordinary windfall gains. In particular, prolonging or deepening the crisis in underdeveloped or weak countries, and exercising tight control over government policies in those countries, can yield bonanzas to international capital.

To understand what is happening in India during the Covid crisis under the Modi regime, and why is the government not willing to increase its expenditure, we need to go into developments in the Indian economy over the past two decades.

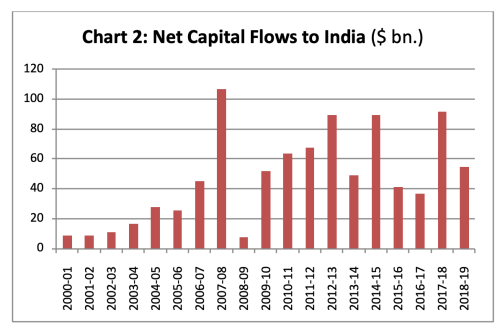

2. India’s Credit Boom

As R. Nagaraj puts it, India’s “dream run” of 2003-08 “was, in fact, a typical credit boom, with its source of finance sowing the seeds of its own destruction.”[4] To draw on his account: As the advanced economies expanded credit massively from 2002, capital flows from these economies to ‘emerging markets’ more than doubled from 2002 to 2007. In India, foreign capital inflows soared to 10 per cent of GDP by 2007-08, the peak of India’s boom.

Less than one-fourth of foreign flows were absorbed by investment. However, they played a larger role in triggering the boom. As foreign capital flowed in, the banking system was flush with funds.[5] Banks now liberally lent to a range of borrowers from infrastructure investors to flat-buyers. The ratio of bank credit to GDP rose from 35 per cent in 2002-03 to 50 per cent in 2007-08.

Source: RBI, Handbook of Statistics on the Indian Economy, 2018-19

Easy inflows of foreign capital fueled bank credit at low interest rates. Foreign investment in the share market led to share prices soaring, enabling companies to raise capital cheaply through new share issues.[6] The private corporate sector more readily took on risky investments and speculative land purchases. The ratio of profit after tax to net worth of firms doubled, from 9.1 per cent in 2002-03 to 18.2 per cent in 2006-07.

With the Government encouraging ‘public-private partnerships’ by the corporate sector with loans from the public sector banks, the share of ‘infrastructure’ (power, telecoms, and roads) in bank credit rose from 9 per cent in 2003 to 33.5 per cent in 2011. At the same time, credit fueled a boom in consumerism of the better-off sections, with the share of personal loans (for housing, automobiles, and consumer durables) in bank credit nearly doubling between 2000-01 and 2005-06. The pattern of production was skewed even further to elite markets, rather than mass consumption. Rapid growth reinforced the prevailing belief that India was at a ‘take-off’ stage, and the endemic problem of demand was now a thing of the past. The Government’s Economic Survey 2016-17 looked back on this period thus:

Firms… launched new projects worth lakhs of crores, particularly in infrastructure-related areas such as power generation, steel, and telecoms, setting off the biggest investment boom in the country’s history…. This investment was financed by an astonishing credit boom, also the largest in the nation’s history, one that was sizeable even compared to other large credit booms internationally. In the span of just three years, running from 2004-05 to 2008-09, the amount of non-food bank credit doubled. And this was just the credit from banks: there were also large inflows of funding from overseas…. All of this added up to an extraordinary increase in the debt of non-financial corporations.

Accumulation Through Grabbing Public Assets, Subsidies, and Natural Resources

As the prospects of rapid accumulation of wealth whetted the appetites of the large capitalists, they turned to the public sector banks for loans and the Government for all sorts of assistance. The boom was thus further fueled by a massive Government subsidies and private sector grab of natural resources (which are not amenable to being valued in money terms, since they cannot be replaced) in the name of infrastructure. India was the world leader in public-private partnerships (PPP) between 2006 and 2012. By end December 2012, it had over 900 PPP projects in the infrastructure sector, at different stages of implementation. But this growth in PPPs was birth-marked with scandal: thus private airports, coal mining (power), and natural gas exploration have been the subjects of critical reports by the Comptroller and Auditor General (CAG).

More generally, the private pillage of natural resources during the ‘boom’ later was manifested in a number of scandals: the manipulation of allocations of radio frequencies for mobile services; illegal mining of iron ore and its export; large-scale land acquisitions for special economic zones (SEZs) in the name of industrial activity, but actually for the purpose of real estate; PPP road projects; and so on. An important aspect of these deals was that, by systematically overstating (‘gold-plating’) the project cost and borrowing the major portion of these overstated costs from public sector banks, many private promoters actually invested no money of their own in the projects. A Reserve Bank deputy governor said that the funding for the PPPs had come so largely from the public sector banks, rather than the promoters’ pockets, that “the ‘Public-Private partnership’ has, in effect, remained a ‘Public only’ venture”.[7]

Since these assets and funds have been alienated from the Indian public, it would stand to reason that, when these private promoters later failed to service their debt, the assets should have come to the hands of the public, and the authorities should have relentlessly pursued private owners for the return of funds, including by expropriating their entire property and arresting them. However, what in fact happens is a second alienation of public assets, as we shall see below.

3. Global Financial Crisis and Two Phases of Fiscal Deficit: Rising and Falling

In 2008 the Global Financial Crisis put a sudden stop to foreign inflows. Credit froze, and growth slumped, worldwide and in India. However, the world’s leading economies, whose own financial sector was endangered, quickly came together to revive global growth. They allowed, even encouraged, the weaker economies and Third World countries to expand their government spending for about two years, approximately India’s fiscal years 2008-09 and 2009-10. In those two years the Centre’s fiscal deficit soared from 2.5 per cent of GDP to 6.5 per cent (see Chart 3 below).

Source: Economic Survey.

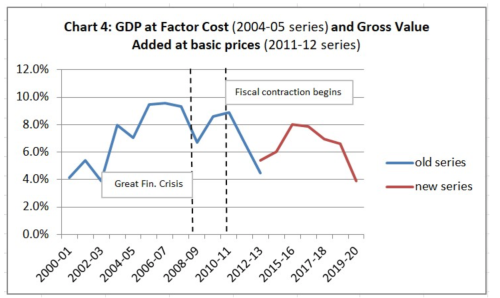

Source: National Statistical Office. Gross Domestic Product at factor cost in 2004-05 series; Gross Value Added at basic prices in 2011-12 series.

In the chart of GDP growth (Chart 4) above, we can mark out different phases.

(i) From about 2003, there was a surge in growth. With large capital inflows and a credit boom, private investment and consumption powered growth. The Government’s fiscal deficits (see Chart 3) meanwhile fell to just 2.5 per cent at the height of the growth boom – which, as is often the case in such booms, came just before the fall.

(ii) In 2008-09, with the Global Financial Crisis, GDP growth slumped.

(iii) However, the Government expanded the fiscal deficit and bank lending in 2008-09 and 2009-10, which led to growth reviving in 2009-10 and 2010-11.

(iv) At that point, the international environment turned hostile once more to public spending. The Government started reducing expenditure once again, and growth slowed once more. (The picture is a bit confused due to the Government’s new series of GDP, base year 2011-12, which overstates GDP growth due to its dubious methods. But even this series shows GVA growth falling from 2016-17 on, finally landing at 3.9 per cent growth in 2019-20, i.e., the same level as 2002-03.)

Why Did Growth Slow Post-Global Financial Crisis Despite Inflows?

One question arises from the above three charts (Charts 2, 3, and 4). As we saw, in the phase 2003-08, inflows of foreign capital fueled rapid GDP growth. They did so despite declining Government fiscal deficits. Yet, in the period after the Global Financial Crisis, while fiscal deficits no doubt declined, India once again received large capital inflows. In fact the average for 2009-10 to 2018-19 was $63.4 billion/year, considerably higher than the average for 2003-08, at $44.4 billion/year. Why then did the second round of inflows not spark the same growth boom as the first?

The most important reason probably was that the rapid growth of 2003-08 was bound to slow at some point precisely because it was not a ‘new normal’ but a bubble. The endemic problem of demand in the Indian economy, which we have referred to elsewhere, had to come to the fore once again. Given the poverty of the Indian masses, they did not constitute an attractive market for big capital. The boom was thus skewed heavily towards elite demand; but the growth of this demand could not be sustained endlessly. The types of economic, social, and political changes required to bring about widespread and evenly distributed increases in demand, and to re-orient production to cater to that demand, were nowhere on the horizon; rather the rulers continued to move aggressively in the opposite direction, destroying livelihoods on a large scale, depressing wages, and concentrating wealth. Hence the boom was fated to peter out.

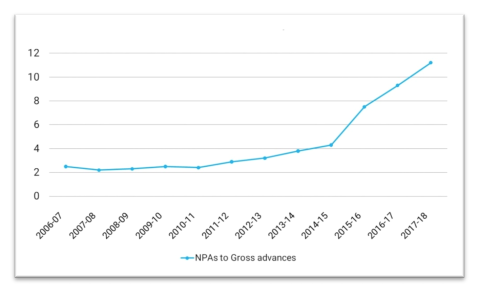

4. The Rajan Regime and Bank NPAs

In mid-2013, former chief economist of the IMF, Raghuram Rajan, was appointed governor of the Reserve Bank of India.

One of his major project concerned the bad debts, particularly the large debts owed to the banks by the corporate sector. Before we come to Rajan’s steps, let us describe the background.

The Economic Survey 2016-17 described the descent into the corporate NPA crisis, and its scale:

…[F]orecast revenues collapsed after the Global Financial Crisis; projects that had been built around the assumption that growth would continue at double-digit levels were suddenly confronted with growth rates half that level. As if these problems were not enough, financing costs increased sharply. Firms that borrowed domestically suffered when the RBI increased interest rates to quell double-digit inflation. And firms that had borrowed abroad when the rupee was trading around Rs 40/dollar were hit hard when the rupee depreciated, forcing them to repay their debts at exchange rates closer to Rs 60-70/dollar.

By 2013, nearly one-third of corporate debt was owed by companies with an interest coverage ratio less than 1 (“IC1 companies”) [meaning they did not earn enough to pay the interest obligations on their loans], many of them in the infrastructure (especially power generation) and metals sectors. By 2015, the share of IC1 companies reached nearly 40 percent…

Accordingly, banks decided to give stressed enterprises more time by postponing loan repayments, restructuring by 2014-15 no less than 6.4 percent of their loans outstanding. They also extended fresh funding to the stressed firms to tide them over until demand recovered.

As a result, total stressed assets have far exceeded the headline figure of NPAs. To that amount one needs to add the restructured loans, as well as the loans owed by IC1 companies that have not even been recognised as problem debts – the ones that have been “evergreened”, where banks lend firms the money needed to pay their interest obligations. Market analysts estimate that the unrecognised debts are around 4 percent of gross loans, and perhaps 5 percent at public sector banks. In that case, total stressed assets would amount to about 16.6 per cent of banking system loans – and nearly 20 percent of loans at the [Government-owned] banks.

[Further,] aggregate cash flow in the stressed companies – which even in 2014 wasn’t sufficient to service their debts – has fallen by roughly 40 percent in less than two years. These companies have consequently had to borrow considerable amounts in order to continue their operations. Debts of the top 10 stressed corporate groups, in particular, have increased at an extraordinarily rapid rate, essentially tripling in the last six years. As this has occurred, their interest obligations have climbed rapidly.

As the economy slowed down further and further after 2010, and the revenues from PPP projects appeared less attractive, private investors stopped work on these projects. The number of PPP projects under implementation fell from 900 in December 2012 to 63 in 2018 and 34 in 2019.[10]

Chart 5: Bank NPAs (as % of gross advances)

Source: R. Nagaraj, “Understanding India’s Economic Slowdown”, The India Forum, Feb 7, 2020.

Despite extensive ‘re-structuring’ of corporate debt, the borrowing firms were not able to revive their financial position, presumably because the bulk of such investments were risky or unsound in the first place. In August-November 2015, the RBI carried out a special inspection of the banks, and found that the banks were using various means to avoid classifying many loans as ‘non-performing’ (i.e., in default). Rajan talked tough and told the banks to re-classify such loans by March 2016. This led to an immediate surge in non-performing assets (NPAs) of banks.

Here we need to distinguish between two things: the responsibility for a phenomenon, and the agenda behind tackling that phenomenon in a certain way. Clearly, the Indian large capitalist class was responsible for the phenomenon of corporate sector NPAs, with the encouragement of foreign finance and the critical help of the Indian State. What was required in response to the NPA phenomenon was the nationalisation of all the assets involved (which were already publicly funded) and the relentless pursuit of corporate defaulters for recovery of diverted funds. By contrast, Rajan’s sudden decision to ‘crack down’ by classifying a much larger number of corporate debts as NPAs was not part of any such national developmental agenda. Rather, it subtly advanced a different agenda, one which would ultimately benefit, not the Indian public, but foreign financial investors.

5. Contracting and Shutting Down the Micro, Small and Medium Sectors

At the same time, the crisis of the last five years has had the effect of contracting the micro, small and medium enterprises (MSME) sector. While official estimates say MSMEs account for 45 per cent of manufacturing output, 40 per cent of total exports, and nearly 31 of GDP, the Government has failed to conduct a census of the sector since 2006-07.[12] The last sample survey of such enterprises was for 2015-16[13], i.e., before demonetisation. The Government follows the untenable procedure of basing its estimates of unorganised sector growth on organised sector growth, thereby systematically concealing the scale of the crisis in the former sector, such as after demonetisation.[14]

In stark contrast to the debt binge in the large sector, the MSME sector has been on a starvation diet. The already meagre bank credit to micro and small units has been falling further as a percentage of total bank credit, from 6.3 per cent in February 2015 to 4.2 per cent in February 2020. The corresponding figures for medium units are 2.2 and 1.2 per cent. Bank credit to such units has even fallen in absolute terms, after discounting for inflation: it has fallen in real terms by 19 per cent for micro and small units, and 33 per cent for medium units.

One telling indicator of the shrinkage of MSMEs is that employment in them has shrunk even as the employment of large and medium firms has slightly grown. According to surveys by the Centre for Monitoring the Indian Economy (CMIE), total employment in the economy fell by 4 million (or 1 per cent of total employment) just after the November 2016 demonetisation; but the annual reports of large and medium sized companies showed a 2.6 per cent increase in employment. This implies that the contraction was entirely in the unorganised sector.

Similarly, after the introduction of the Goods and Services Tax (GST), which imposed taxes and costs on small businesses that they were unable to bear, total employment shrank a further 5 million (betwen 2017 and 2018); whereas the larger companies, listed on the stock market, reported a 4.7 per cent increase in employment. As Mahesh Vyas points out, “This was expected because the GST helped the larger and more [GST]-compliant companies take over the market shares vacated by the small enterprises. It is therefore quite likely that the brunt of the shocks of demonetisation and the consequent economic slowdown thus far since 2017 has been borne by the unorganised sectors.”[21]

The SME Chamber of India estimates that close to one million manufacturing units have closed since the end of 2016, due to demonetisation, GST, and the lack of bank credit.[22]

It should be added that in an underdeveloped country like India, where the unorganised sector makes up the overwhelming bulk of employment, survey data do not directly reveal the full extent of unemployment. Those working in the unorganised sector have no unemployment insurance to fall back on, and therefore keep on working even if the income from such work is below subsistence levels. They are then recorded as ‘employed’, whereas in any meaningful sense they are unemployed, to one extent or the other.

6. Result: Major Restructuring of India’s Economy on the Cards

Thus, even before the Covid-19 crisis, the consequences of the above developments were as follows:

(i) With the collapse of the credit bubble of 2003-08, and the gradual slowing down of the Indian economy, the only means by which the rulers could have revived growth within the existing frame was through Government spending.

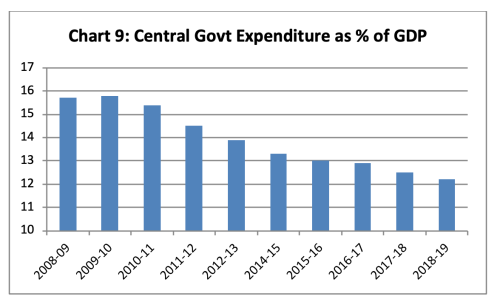

(ii) However, external pressure ensured that the Government steadily reduced its spending as a proportion of GDP from 2010-11 onwards, which in turn ensured that growth would slow down (Chart 9). (The demonetisation of 2016 and the introduction of GST thereafter also dealt blows to the unorganised sector, where the bulk of non-agricultural workers are employed, and thus further depressed demand and growth.)

Slowing growth also punched gaping holes in the Government’s tax revenues: the 2018-19 net tax revenues of the Centre, which were budgeted at 7.9 per cent of GDP, turned out to be just 6.9 per cent, a shortfall of Rs 1.6 lakh crore. The shortfall in tax revenues resulted in the Centre’s spending being cut by a further Rs 1.2 lakh crore in 2018-19 in order to keep down the fiscal deficit. This spending cut further slowed the economy.

(iii During the period up to 2010-11, the corporate sector had borrowed from public sector banks and made investments on the basis of extravagant projections of growth. Once growth slowed, and the Government would not spend in order to revive it, large segments of the corporate sector were not earning enough to meet their interest obligations. Generous ‘restructuring’ of their debt, including by surreptitiously providing them fresh loans to service their earlier ones, provided the promoters escape routes, but could not financially revive these projects.

(iv) In the period after 2010-11, the corporate sector also built up a heavy load of external commercial borrowings, rising from $70.7 billion in March 2010 to $223.8 billion in December 2019, i.e., a growth of $153 billion, or Rs 10.9 lakh crore at the then prevailing exchange rate. It created a ticking time bomb, since it was largely contracted on the dangerous assumption that the rupee-dollar exchange rate would remain stable. Any sharp fall in the rupee’s value would send borrowing firms into a crisis.

(v) The above situation implies that, in a situation of crisis, both the Government and the private sector would part with assets, albeit for different reasons:

- The private sector would do so because that is the defined course under capitalism for a firm that cannot sustain its debt burden.

- The Government would do so on the excuse of reducing the fiscal deficit. However, that is not the reason it parts with assets – the real reason is dictates of international capital.

(vi) During a crisis, assets are inevitably sold at distress prices; and the only parties with the cash to buy them may be foreign firms, and perhaps a handful of large Indian firms with special access to liquidity.

(vii) As we saw above, the pre-Covid crisis had already brought about a destruction of unorganised sector enterprises. Now these enterprises have been hit even more severely by the lockdown, and the risk is not confined to the micro and small units. What is crucial to grasp is that this shift is not temporary: many enterprises and livelihoods will not return.

We already have an economy in which the levels of employment are very low by world standards – less than 40 per cent of the working-age population is employed.[26] These low employment levels are now set to fall further. This high-unemployment economy will become the ‘new normal’.

(viii) At the same time, in an effort to revive the ‘animal spirits’ of corporate investment amid a drought of demand, the State is carrying out aggressive changes (‘reforms’) to reduce wages, demolish the lingering remnants of workers’ legal rights, make acquisition of peasant land easier, remove all restrictions on private capital in various sectors such as mining, and in general promise private capital greater ‘ease of doing business’ (even making state government’s ability to borrow contingent on their fulfilling ‘ease of doing business’ norms set by the Centre).

(ix) Taken together, this is a comprehensive, multi-layered restructuring of the Indian economy. Labour is restructured in favour of capital; small firms are restructured or destroyed in favour of big capital; the public sector is cannibalised by private capital; and the domestic economy as a whole is restructured in favour of foreign capital.

Silent Wave of Foreign Takeovers in the Private Corporate Sector

Foreign portfolio investors’ (FPIs’) holdings in the Indian share market are very large – they own over 40 per cent of non-promoter holdings of the Nifty-500. Thus FPIs, taken as a bloc, have overwhelming impact on the share market. At the time of a crisis, FPIs tend to exit some of their holdings, and the market as a whole moves downward. When that happens, the market value of FPI holdings falls. However, like any canny investor, FPIs use periods of downturn in the share market to buy shares at low prices. The returns over the years have been huge: The historical value of FPI into Indian equities (i.e., the sum of all the foreign capital inflows into the Indian share market) was $149 billion at end-December 2019[27]; but the market value of FPI holdings on that date was above $463 billion[28], i.e. more than three times more. Thus the Indian share market will offer more ‘buying opportunities’ for FPIs as prices head further down in coming months.

In research reports and the financial media, the debt crisis of the Indian corporate sector is presented quite frankly as a goldmine for foreign investors. The US-based consulting firm McKinsey says:

The restructuring of stressed loans, which amounted to $146 billion on banks’ books in December 2017, will create a one-time opportunity for investors with the risk appetite and operational turnaround expertise in several sectors needed to deploy capital at scale.

In the last three years, there has been a surge in the number of ‘control deals’ (i.e., when a firm changes hands) by foreign investors. In 2017-18, Indian investors accounted for 76 per cent per cent of control deals in India, but in 2018-19, the situation was reversed: foreign investors accounted for 79 per cent of such deals.[29] The trend has continued in 2019-20.

Among such foreign investors are foreign firms as well as different types of investment funds, including ‘private equity’ (PE) funds. PE funds raise capital from institutions or individuals, and directly invest in private companies by negotiation with the promoters. They may buy either minority stakes, controlling stakes or the entire share capital.

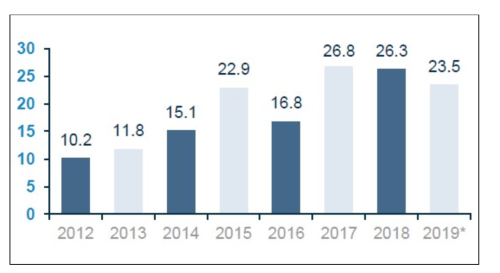

According to a November 2019 report commissioned by the Confederation of Indian Industry (CII), foreign PE firms invested $133.4 billion in Indian firms between January 2012 and August 2019, with the figure rising sharply in the last five years, and the size of deals growing. Earlier, foreign PE investors in India tended to be passive, but now deals in which PE firms gain control of the target firm have risen to $9.9 billion in 2018. PE firms have now reportedly earmarked $100 billion to invest in Indian firms.[30]

Chart 10: Historical Private Equity Investments (US $ billion)

Data for 2019 cover only January-August.

Source: Alvarez and Marsal, op. cit., based on Bain Private Equity Report 2019 and VCC Edge. Figures include venture capital investments.

In earlier years, the managements of larger Indian firms had effectively resisted takeover bids. Hence PE firms targeted smaller or newer enterprises.

It in fact discovered an opportunity in these investments, which could be termed “predatory lending”. On the flip side, promoters of many Indian firms sought to leverage such foreign funds to leapfrog into the big league, overlooking the downside risks of high costs of external debt in terms of domestic currency (when market conditions turned adverse).[31] This is what led to the promoter of Cafe Coffee Day committing suicide in 2019. He left behind a note to the board that he was under pressure from a private equity firm, as well as lenders and the tax authorities.

As the growth slowdown persists, an increasing number of large firms find it impossible to climb out of their debt traps. Fitch Ratings estimates stressed corporate debt in India at $260 billion, and major groups such as the Jaypee Group, Anil Dhirubhai Ambani Group, Lanco and Essar faced insolvency. As a result, a growing number of large Indian corporate firms have either had to sell important assets to foreign investors, or surrendered control of their firms. According to a senior partner of the law firm AZB and partners, “given the stressed landscape, the number of control deals is likely to increase”.[32]

A few instances of asset sales, either completed or being negotiated, are given below (collected from media reports).

Table: Some examples of sale/prospective sale of assets to foreign investors

by debt-stressed Indian promoters

| Indian Promoter | Asset | Foreign Purchaser (actual/prospective) | Comments |

| Max Group | Corporate hospital chain (13 hospitals) | PE major KKR-backed Radiant Life Sciences | |

| Max Group | Max Bupa health insurance | True North (PE firm) | |

| Anil Ambani | Mutual fund (43% stake) | Nippon Asset Management | Sold for Rs 6,500 crore |

| Anil Ambani | Home finance company – majority stake | Talks with global investors on | |

| S. & R. Ruia | Refinery | Rosneft-led consortium | Sold for Rs 72,000 crore |

| S. & R. Ruia | Aegis BPO | Capital Square Partners (PE firm) | Rs 4,400 crore |

| S. & R. Ruia | Equinox office complex, Mumbai | Brookfield (PE firm) | |

| Capt. Nair & family | Four marquee hotels | Brookfield (PE firm) | Rs 3,950 crore |

| B.M. Khaitan | Eveready Batteries | Talks on with Duracell, Energizer | |

| DHFL | Avanse financial services | Warburg Pincus PE | Several Indian bidders backed out for lack of funds |

| DHFL | Aadhar Housing financial services | Blackstone PE | |

| GMR Infrastructure | 49% stake in GMR airport business | Groupe ADP (France) | Sold for Rs 10,780 crore |

| GVK Group | Bengaluru airport – entire 43% stake | Fairfax PE | Helped bring down group debt significantly |

Source: Media reports

Foreign investors have also taken over a number of road projects from debt-stressed Indian promoters. Presumably the banks which lent large sums for such projects have taken sizeable ‘haircuts’, which may later require recapitalisation of the banks by the Government:

In a new trend in the road infrastructure space in India, pension funds, sovereign wealth funds and private equity funds from Canada, Abu Dhabi, Australia and Singapore are seen emerging as new owners of road assets… So far, these funds have collectively pumped in about ₹20,000-₹25,000 crore in up-and-running road assets and more funds are on their way…. What this means is that other than NHAI, foreign investors are controlling a certain percentage of India’s road assets.”[33]

A Bloomberg report notes that foreign financial investors in India are not interested in new ventures; rather they are keen to buy Indian assets at depressed prices: “Distress is all that excites PE investors now.”[34] The greater the depression, the greater the distress, and the greater the scope for foreign investors to pick up assets at distress prices.

Importantly, especially after the collapse of the giant private lender IL&FS in September 2018, the entire ‘non-banking financial corporation’ (NBFC) sector found it difficult to borrow money. As mentioned earlier, a large number of such NBFCs borrowed abroad in the last two years. However, many firms to which the NBFCs lent to may find themselves in dire straits as the economy goes deeper into depression in the coming period. If the debtor firms default, the NBFCs may come to control them. At the same time, the NBFCs themselves may be unable to service their debt to foreign lenders. In such a situation, foreign lenders may come to effectively control sizeable assets of non-financial firms.

Implications of foreign takeovers

In the boom phase, as we discussed above, the Indian private corporate sector’s PPP projects received a range of bounties from the Government – subsidies, tax concessions, cheap land, free or undervalued Government-owned infrastructure, and so on. The public sector banks provided loans for these projects. Thus the projects themselves were a form of alienating public assets.

However, now that the Indian private promoters have defaulted on the loans, many of these projects are being transferred to foreign investors, and the banks are accepting large ‘haircuts’ (as much as 85 per cent) on the sums due to them. This amounts to a large transfer of India’s public wealth to foreign investors, on distress terms – a second alienation, as it were.

Further, as foreign investors own an increasingly larger share of the Indian corporate sector, the drain from India will increase. One has only to look at the drain from India on account of just one foreign-owned company, Maruti Suzuki, to get a sense of this.

Privatisation

The US-based consultancy, Boston Consulting Group, now a key advisor to the Indian government on the Covid crisis, spelled out in 2018 what it called “The $75 Trillion Opportunity in Public Assets”:

Governments around the world are under enormous financial pressure. Budgets remain constrained in many countries while the need for investment – particularly in infrastructure – is growing. A solution, however, is hiding in plain sight. Central governments worldwide control roughly $75 trillion in assets, according to conservative estimates – a staggering sum equal to the combined GDP of all countries…. Government leaders must take aggressive action to harness the value of the public assets under their control… Governments should consider three main transaction models: Corporatization… Partnerships… Privatization.”[36]

A major, even central, gain for foreign investors from the regime of fiscal ‘austerity’ is that it invariably includes a programme of privatisation. The pressure to reduce the fiscal deficit is, as it were, the lever. The prize is public assets.

As such, even within the framework of orthodox economics, there is no justification for linking privatisation to an attempt to bridge the fiscal deficit (i.e., the gap between spending and revenues, which is made up by borrowing). After all, privatisation is the sale of Government assets; but the fiscal deficit is largely made up of current (recurring) expenditures, which create no assets. Selling assets to pay for running expenses is a recipe for a deeper mess. Hence privatisation must be dressed up as ‘reducing the burden of the public sector on Government finances’, ‘increasing efficiency’, ‘increasing national wealth’, and so on, and so forth. We can easily judge the worth of this argument by noting that, in practice, the Government does not use the proceeds of privatisation to invest in other long-lasting, efficiency-improving assets. It merely credits the proceeds of privatisation to its ‘non-tax revenues’; that is, it uses it to meet its running expenses.

The ‘Prime Minister’s Economic Package in the fight against Covid-19’, as presented by the Finance Minister over five days, remarkably contained virtually nothing related to public health. Rather, the centrepiece was privatisation – of the coal sector, of the mineral sector, of airports, of electricity distribution, of the defence industry, of atomic energy, of ‘social infrastructure’ (related to education, healthcare, water supply, sanitation, etc.), of the space programme. Whether or not private investments in all these fields materialise, one point was categorically stated: virtually all public sector enterprises, barring a handful, are to be sold off:

Government will announce a new policy whereby –

List of strategic sectors requiring presence of PSEs [public sector enterprises] in public interest will be notified.

In strategic sectors, at least one enterprise will remain in the public sector but private sector will also be allowed.

In other sectors, PSEs will be privatized (timing to be based on feasibility etc.)

To minimise wasteful administrative costs, number of enterprises in strategic sectors will ordinarily be only one to four; others will be privatised/ merged/ brought under holding companies.

The list of “strategic sectors” has not yet been spelled out, but it is thought to contain atomic energy, defence and the space programme; other possibilities include oil and gas, telecom, and banking and financial services.

The scale of the proposed sell-off is staggering. The Economic Survey 2019-20 says there are about 264 Central public sector enterprises (CPSEs) under 38 different Ministries/Departments. Note that this agenda was in fact underway well before Covid-19 and the Prime Minister’s ‘Economic Package’; the pandemic merely offered an excuse for advancing it even more aggressively.

This year, the Government has set an unprecedented target of Rs 2.1 lakh crore in disinvestment receipts. That means that investors with an appetite for shares in India’s public sector will have a larger choice. In such a situation dumping more assets on the market will simply drive prices down even further. Nevertheless, as tax revenues are certain to collapse this year, the Government will try to sell even more assets in an attempt to keep the fiscal deficit down. The pressure on the Government to do so has increased, with Moody’s now downgrading India, citing, among other things, the deteriorating fiscal position of the Government and its weak implementation of ‘reforms’. A key ‘reform’ desired by the credit rating agencies is privatisation.

References

[4] R. Nagaraj, “India’s Dream Run, 2003-08: Understanding the Boom and Its Aftermath”, Economic and Political Weekly, May 18, 2013.

[5] As the supply of dollars increases in the foreign exchange market, the rupee’s value tends to rise. This would have a harmful impact on Indian producers, since imported goods would become cheaper in rupee terms, and Indian exports would become more expensive in dollar terms. Hence, in response to a rise in inflows, the RBI intervenes to buy up the dollars, which it adds to its foreign exchange reserves. In exchange for these dollars, the RBI pays rupees. These rupees end up in the banks. Hence the banks have additional funds with which to lend.

[6] The higher share prices rise, the heftier the premium (over the face value of the share) that companies can charge when raising money from the public through fresh share issues.

[7] K. C. Chakrabarty, “Infrastructure Financing by Banks in India: Myths and Realities”, RBI Bulletin, September 2013.

[10] https://ppi.worldbank.org/content/dam/PPI/documents/private-participation-infrastructure-annual-2019-report.pdf

[12] Radhika Pandey and Amrita Pillai, “Covid-19 and the MSME sector: The ‘identification’ problem”, Ideas for India, April 20, 2020. https://www.ideasforindia.in/topics/macroeconomics/covid-19-and-the-msme-sector-the-identification-problem.html

[13] National Sample Survey, 73rd Round, Unincorporated Non-agricultural Enterprises (Excluding Construction), 2015-16.

[14] Akshay Deshmane, “Indian Economy In Recession Thanks To Demonetisation, Says Economist Arun Kumar”, Huffington Post, November 13, 2019, https://www.huffingtonpost.in/entry/indian-economy-recession-demonetisation-black-money_in_5dc53e34e4b00927b231296c

[21] Mahesh Vyas, “An ominous confluence”, https://www.cmie.com/kommon/bin/sr.php?kall=warticle&dt=2020-01-14%2012:06:19&msec=953&ver=pf.

[22] Namrata Acharya, op. cit.

[26] As Vyas points out, India’s labour force participation rate – i.e., the percentage either employed or seeking work – is about a third less than the global average of 66 per cent. Employment levels are less than 40 per cent. “Surveying India’s unemployment numbers”, Hindu, February 9, 2019. https://www.thehindu.com/opinion/lead/surveying-indias-unemployment-numbers/article26218615.ece

[27] RBI, International Investment Position of India, end-December 2019.

[28] Motilal Oswal, “India Strategy”, May 27, 2020.

[29] Surajeet Das Gupta and Sachin Mampatta, “Foreign investors picking controlling stakes in companies on the rise”, Business Standard, June 8, 2019.

[30] Alvarez and Marsal, “India’s M&A and Distressed Opportunity Landscape”, Confederation of Indian Industry, September 2019.

[31] Nagaraj, “India’s Dream Run”.

[32] Ridhima Saxena, “PE funds increasingly look for buyout deals in India”, Mint, May 12, 2019. .

[33] Lalatendu Mishra, “Foreign funds ‘take over’ Indian road assets”, Hindu, September 18, 2019. https://www.thehindu.com/business/foreign-funds-take-over-indian-road-assets/article29452321.ece

[34] Andy Mukherjee, “Private equity spots profit in India’s distress”, Bloomberg, November 8, 2019

[36] Boston Consulting Group, “The $75 Trillion Opportunity in Public Assets”, 2018. Regarding their role as advisors to the Indian government on Covid, BCG admits: “We don’t claim we are epidemiologists. But we certainly know what crisis reforms should be.”

(Research Unit for Political Economy is a trust based in Mumbai that brings out material seeking to explain day-to-day issues of Indian economic life in simple terms and link them with the nature of the country’s political economy.)