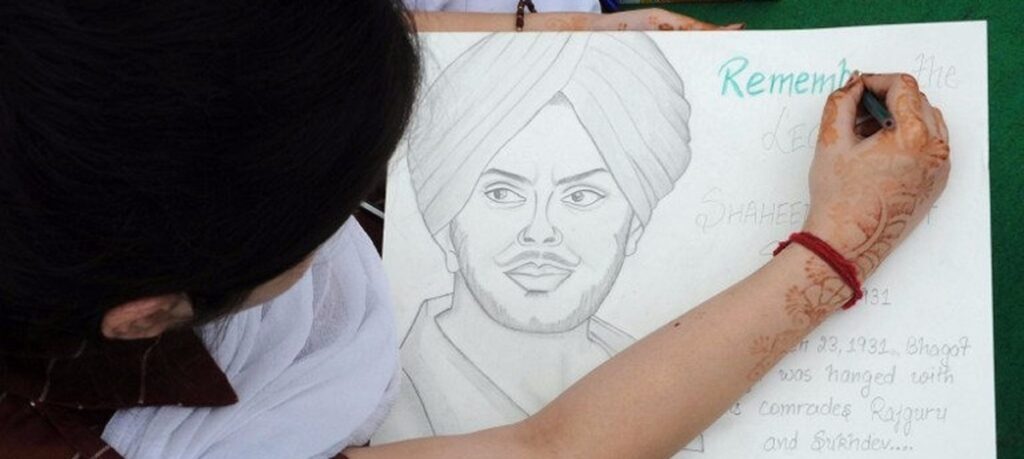

For nearly 90 years, India has been living in nostalgia of an iconic youth – Bhagat Singh. A sense of loss informs our discourse on Bhagat Singh. We keep turning to him and Subhas Chandra Bose again and again as sources of deliverance from the ills that India has been suffering. It’s too heavy a burden considering that Singh was just 23 years old when he was hanged.

Bhagat Singh is seen as the ultimate militant nationalist. Nationalism cannot do without militancy. It is believed that Mahatma Gandhi and his heir, the effeminate Jawaharlal Nehru, emasculated us and also conspired to remove two “real men” from the scene in Bhagat Singh and then Subhas Chandra Bose. It is quite a different matter that Bhagat Singh did not want youth to emulate Bose. In the young Singh’s eyes, Bose was an emotional nationalist with a parochial outlook. He considered Bose dangerous for the youth as his rhetoric could arouse nationalistic passions easily.

Bhagat Singh is seen as the quintessential nationalist who paid with his life for avenging the death of another “Hindu” nationalist, Lala Lajpat Rai. Singh and his comrade Chandra Shekhar Azad formed part of the core of the Hindustan Socialist Republican Army. He threw bombs in the Central Legislative Assembly and courted arrest. He refused to seek pardon when sentenced to death. He emerges as a figure who is nothing if not a militant nationalist.

The revolutionary

And yet, Bhagat Singh is not the militant nationalist in the sense popular culture has constructed him. His final act of throwing bombs in the assembly was not only for some “nationalist” cause, but mainly to protest the Public Safety Bill and the Trade Disputes Bill – the latter sought to strip workers of their rights and crush their protests. It’s crucial to keep in mind the content of protest, especially in these times when governments are introducing new laws to deprive workers of their rights and outlaw attempts to even protest such curtailment, apart from using laws like The Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act to suppress all popular movements. The legacy of Bhagat Singh’s protest would be honoured only if we oppose governments and the State, which stand on the side of capital at the cost of the well-being of the working masses.

His slogan was “Inquilab Zindabad”. “Inquilab”, which means revolution, is not a word from the nationalist lexicon. In a letter to the editor of the Modern Review, who had criticised the slogan “Inquilab Zindabad”, Bhagat Singh and fellow revolutionary Batukeshwar Dutt explained that the cry of “Long Live the Revolution” never meant a ceaseless armed battle or a permanent state of anarchy, that bombs or pistols cannot be a synonym of revolution, even if in certain conditions they might be an important means to a desirable end.

Revolution is a desire for transformation to achieve progress. Very often, people tend to get stuck in ordinary, secure traditions and the mere thought of change frightens them. It develops into an inertia which shackles the movement of society and becomes an obstruction. Revolution is, therefore, essential to the growth of humanity. It is a call for constant renewal. Old must give way to the new.

Another facet of Bhagat Singh’s ideology was that he was an internationalist, unlike other revolutionaries whose concerns remained essentially Indian. It is not surprising that he felt drawn to Nehru, who in his view had an internationalist approach. And so it would be more appropriate to call Bhagat Singh’s struggle anti-colonial and anti-imperialist, rather than nationalist.

Deep thinker

Bhagat Singh’s writings bring out a person who is seeking to evolve a method of thinking. He does not believe in merely making assertions which should be accepted simply because they come from a man who has sacrificed everything for the nation. He not only argues with people like Gandhi who are outside his fold and with whom he enters into a polemical battle in his famous pamphlet “Philosophy of the Bomb” – initially authored by Bhagwati Charan Vohra – but also his fellows in the revolutionary movement on issues such as love and atheism.

Most of the revolutionaries were religious, with many of them devotees of Kali or Shakti. Bhagat Singh’s atheism did not make him very popular in this crowd. He tried to explain his atheism in the pamphlet headlined Why I Am An Atheist by first responding to the charge of his colleagues that it was his arrogance that made him a non-believer. He argued that it was not his arrogance, but his realism and rationality that led him to doubt the existence of god. He believes in nature and thinks that it would be more useful to this reality, not as creation of some supernatural force, but as a result of the dynamic forces of nature and society.

Knowledge is power

We know from the reminiscences of his friends and colleagues that Bhagat Singh was not a puritan. He valued the gift of life and did not want to smother the feelings of love and beauty for the cause of revolution. In short, he was not a renouncer. At one point of time, his co-travellers saw him as weak and so to dispel this notion, Singh volunteered to be part of the action which finally led him to the gallows.

What is most striking about Bhagat Singh is his passion for reading and writing. His wanderings as an underground militant could not keep him away from books. For him, reading was essential for growing as a human being. Even when faced with imminent death, he kept reading and taking notes. It was as if he was reading not only for himself, but for posterity as well. He was also a regular writer, contributing to magazines like Matwala and Pratap.

What distinguishes Bhagat Singh from other revolutionaries is his passion for thinking. He disliked rhetorical statements and stressed on the need to develop understanding through a process of argumentation. His careful reading of the history of the revolutions led him to conclude that revolutions were not made by bombs and pistols – the most important thing was to mobilise people, a far more difficult prospect. The real battle was the battle of hearts and minds.

Bhagat Singh remains an eternal youth. But he is a difficult act to follow. Becoming a youth like Bhagat Singh involves first moving away from the beaten path, to look for new ideas, to be courageous enough to be a loner, not believe in any deity, and to keep questioning the power of the day.

(The author teaches at Delhi University. Courtesy: Scroll.in.)