In the early hours of January 1, Monika Solanki saw a long convoy of government vehicles and massive container trucks going past her home in Madhya Pradesh’s Tarpura village. Fire engines and ambulances followed, all moving at a steady speed towards a nearby industrial sector in Pithampur.

The 12 leak-proof trucks were loaded with 337 metric tonnes of toxic waste from the Union Carbide India plant in Bhopal – the site of an industrial disaster in which leaked methyl isocyanate gas killed thousands in 1984.

The toxic waste was shifted after the Jabalpur bench of the Madhya Pradesh High Court gave a four-week deadline to the state government to remove it from the Union Carbide factory.

As the trucks headed to a hazardous waste disposal plant in Pithampur, an industrial town with villages on its periphery, protests erupted. On January 3, a violent clash broke out at a protest by residents in Pithampur. As the police lathi-charged protestors, two men, Raj Patel and Rajkumar Raghuvanshi, poured petrol on their bodies and set themselves on fire.

“We have been anxious since those trucks arrived. They are all parked inside the plant,” said 30-year-old Solanki, whose village is less than a kilometre from the plant.

Residents fear that the treatment of waste may affect their health and immediate environment. They also allege that the process has been shrouded in mystery.

“The incineration is happening without involving all stakeholders and especially the inhabitants of Pithampur and Indore,” said Amulya Nidhi from Jan Arogya Abhiyaan, an organisation that works on health issues. “That is the reason why people are protesting.”

Jitu Patwari, Madhya Pradesh Congress president, pointed out that the streams near the waste disposal plant empty into the Yashwant Sagar dam that supplies drinking water to Indore.

“Not just Pithampur, the population of Indore will also get affected if toxic waste is released in the environment,” he told Scroll.

Activists pointed out that moving 337 metric tonnes of toxic waste from Bhopal was a token gesture that could do more harm. “What the Madhya Pradesh government has done is remove the surface toxic waste from inside the plant [when there is much more waste left],” said Rachna Dhingra, from the Bhopal Group for Information and Action, a group of activists and survivors of the Bhopal gas tragedy. “This is an eyewash.”

A 2015 trial run

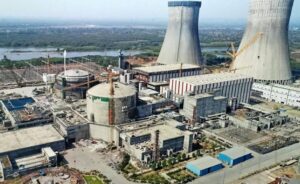

The Ramky Enviro Engineers Ltd waste disposal plant is surrounded by 12 villages, the closest being Tarpura.

Several residents said they were sceptical about the plant’s ability to handle such toxic waste.

“We don’t believe Ramky has the required technology to burn such hazardous waste,” said Hemant Hirole, a resident of Tarpura village. “That waste is toxic and has already killed thousands in Bhopal.”

Hirole alleged that since the Ramky plant was set up in 2010, the environment has been damaged. “The water in our wells has become polluted. Fishes and frogs have died,” Hirole said. He added the production of wheat, maize and soybean on his fields have been affected by the discharge from the plant. We are demanding a complete shutdown of the plant.”

Residents also pointed out that a small amount of waste from the Union Carbide plant – 10 metric tonnes – had been burnt as part of a trial run in 2015. In a press conference on January 2, Madhya chief minister Mohan Yadav said the “report [of the trial run] revealed that the disposal of the hazardous waste has no impact on the environment.”

However, Amulya Nidhi, from Jan Arogya Abhiyaan, said they surveyed the area after that trial run. “The local water bodies had turned black. Agricultural output had declined,” he told Scroll.

Chaman Chopda, another resident from Tarpura, said after the 2015 episode, many residents began to complain of skin problems.

“Our skin was itchy and irritated. The water got so polluted that we can’t use it for drinking, bathing or for agriculture,” he said. “Banjar zameen ho gayi hai yahan,” he added. The land has turned barren.

Gautam Kothari, president of Pithampur Udyogik Sangathan, an association of all industries in Pithampur, however, said that the pollution in the area is caused by multiple factories. “This is an industrial sector. Several other industries are responsible for polluting the local stream,” he said.

Kothari said that the fears about the Ramky plant being incapable of treating the waste was unfounded. It has upgraded its facility and installed a multi-effect evaporator, he said. “It now has the necessary equipment to handle the toxic waste of Bhopal,” Kothari said.

Dhar collector Priyank Mishra, under whose jurisdiction Pithampur falls, did not respond to queries from Scroll.

A resident of Pithampur, Rajesh Chaudhary, has filed a fresh petition in the Madhya Pradesh High Court against the government’s plan to incinerate waste in the area. He has also challenged Ramky’s expertise in incinerating the toxic waste and asked for a stay order.

Pithampur has a population of close to 1.80 lakh.

The hearing is slated on January 8. “Earlier, there were plans to incinerate the waste in Gujarat and Maharashtra,” Chaudhary said. “Both states opposed it and the plan was dropped. Why is Pithampur being targeted despite our opposition?”

Solanki, a mother of two, said that most of the residents of villages near Pithampur are labourers and farmers. “If poisonous gas leaks and causes health issues, we don’t have the money required to get treatment.”

She added: “Everybody remembers the horror people in Bhopal faced in 1984. We don’t want a repeat.”

The process

The central government has approved Rs 126 crore for the incineration of 337 metric tonnes of waste, of which 20% funds have already been released to Ramky Enviro.

The government will first burn a small quantity of waste and submit a report to the Jabalpur High Court.

It plans to then incinerate the waste by 90 kg every hour, a process also followed in 2015. It can take up to six months for the entire toxic waste to be treated.

The waste will be burnt at a common hazardous waste treatment, storage and disposal facility inside the Ramky plant. The waste will be put inside a hot, rotary kiln at 850 to 1,200 degree Celsius and then a combustion chamber. Air pollution control devices called scrubbers will be used to neutralise the toxic gases produced by burning the waste .

But Dinesh Kothar, a local activist, said a huge population is at risk of exposure to toxic waste if remnants are released in air or if they contaminate soil and water. “Why didn’t the government create a facility to dispose of waste within Bhopal?” he asked.

What is left behind in Bhopal

A 2010 report submitted by National Environmental Engineering Research Institute found the soil in and around the Union Carbide plant was contaminated with pesticides like benzene hexachloride, aldicarb and arbaryl, besides α-naphthol and mercury – the chemicals can lead to neurological damage, lung toxicity, memory loss and motor dysfunction.

The amount of soil in and around the plant is 11 lakh metric tonnes, according to the report.

Rachna Dhingra, from the Bhopal Group for Information and Action, said there is a significant amount of toxic waste left in the soil, in the dump pits and solar evaporation ponds in Bhopal.

The Union Carbide had made 21 dump pits containing toxic waste inside the plant, and in 1977 created solar evaporation ponds on a plot of 32 acres outside to act as landfills to store toxic waste material. “Even if the 1984 gas leak had not occurred, the issue of contamination from these ponds existed. The government is not even talking about cleaning this,” Dhingra said.

A population of 1.2 lakh is currently being exposed to this contamination around the Union Carbide plant in Bhopal, she added.

Dhingra said that taking this waste to Pithampur will only expose more people to the risk of contamination. “The government should force the owners of Union Carbide to take this waste outside India and treat it. We do not have the technical capability to tackle it.”

(Tabassum Barnagarwala covers health, women and child development, and rural development for The Indian Express. Courtesy: Scroll.in, an Indian digital news publication, whose English edition is edited by Naresh Fernandes.)