[In December 2002, Isabel Crook, a Canadian anthropologist who had spent most of her life in China and a longtime friend and supporter of Monthly Review, wrote a letter to the MR editors questioning the critical nature of Monthly Review’s coverage of China’s capitalist road to socialism since the ascendance of Deng Xiaoping in the late 1970s. In the 1990s and early 2000s, Monthly Review and Monthly Review Press had published such works as William Hinton’s The Great Reversal (1990), Robert Weil’s Red Cat, White Cat (1996), and Nancy Holmstrom and Richard Smith’s “The Necessity of Gangster Capitalism” (February 2000), all of which were highly critical of developments in China. Crook, now 106, was awarded the Medal of Friendship by Chinese President Xi Jinping in 2019. We are republishing this short exchange as it reflects the complex ways in which dedicated socialists sought to address changes in China and the clarity of the ideas expressed. This was particularly the case with respect to Harry Magdoff, who saw China as a postrevolutionary society, neither socialist nor capitalist, but also having shifted in the direction of the latter. The question, then, as now, was whether China would “one day… return to the goals of giving first priority to the needs of the people.” These letters have been edited to remove personal comments.

—The Editors, Monthly Review]

Isabel Crook to Monthly Review Editors

(Beijing Foreign Studies University, December 3, 2002)

There is one matter I would like to raise for your consideration. Much as I have valued Monthly Review, I regard your coverage of China and her turn to capitalism as one-sided. My view is that in the Mao era the Chinese people “stormed the heavens!” But, to quote [Bertolt] Brecht, “The house was built with the stones that were there.” So there were mistakes and setbacks by the late 1970s, China was in a weakened position externally due to the split in the Socialist camp and internally due to the upheavals of the Cultural Revolution. I regretted the turn from Mao’s strategy to Deng’s. But, if in her vulnerable position China required speedy economic development, for her own security, then Deng’s choice was valid. It certainly brought rapid economic development and a strengthening of China’s international standing. Therefore, whatever hopes we may once have pinned on China, what right have we to blame her for abandoning Mao’s strategy?

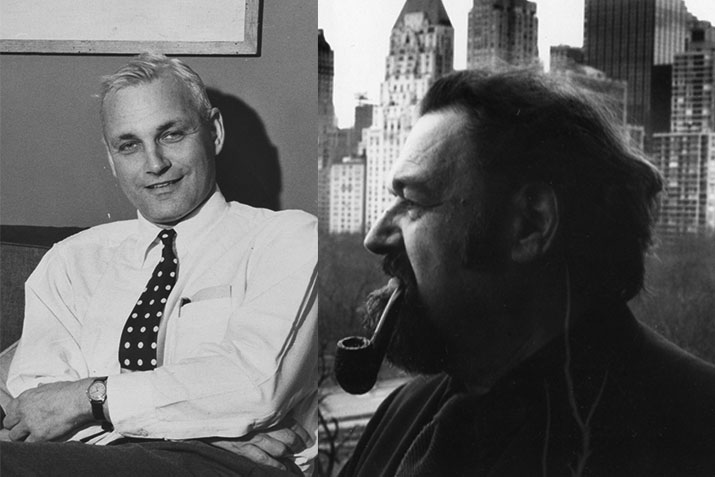

Harry Magdoff to Isabel Crook

(February 5, 2003)

I am interested in your concern about the one-sided view of China in MR articles. As one-sided as they may be, they are not intended to be an attack on China. Granted that our knowledge of China is necessarily limited, we still have a responsibility to analyze developments there from a Marxist point of view. Furthermore, frank debate is useful and necessary. Even ruthless criticism is often in order. Name calling is hardly the issue. But to the extent that names may at times be needed, I would not call China capitalist. Major economic heights are nationally owned and centrally planned. In addition, competition between private firms are not the determinants of the economy’s laws of motion. (The latter is a key feature of a capitalist society.) Nevertheless, the changes that have been taking place do increasingly take on features of a capitalist society, plus being part of a trend moving more and more toward a society resembling capitalism. Let me give you a major significant. In the early 1970s, China had the most egalitarian society in the world, and the drift was toward more equality—a unique historical phenomenon. Today, the distribution of income in China is almost identical with that of the United States. The source of the information on income distribution comes from the World Bank, of which China is a member. Much more needs to be examined, especially in view of China’s joining the WTO [World Trade Organization].

I don’t think it needs to be said that I love China, and hope that one day it will return to the goals of giving first priority to the needs of the people. Of course, China has faced severe problems after the inner upheaval and changes taking place in other parts of the world. Reforms were no doubt badly needed. But there were different ways to stabilize and move ahead. The choice Deng made was not the only feasible one; also, it produced its own contradictions. If contradictions are the essence of human development, then we should make room for responsible debate.

(Courtesy: Monthly Review, an independent socialist magazine published monthly from New York City since 1949, whose present editor is John Bellamy Foster.)