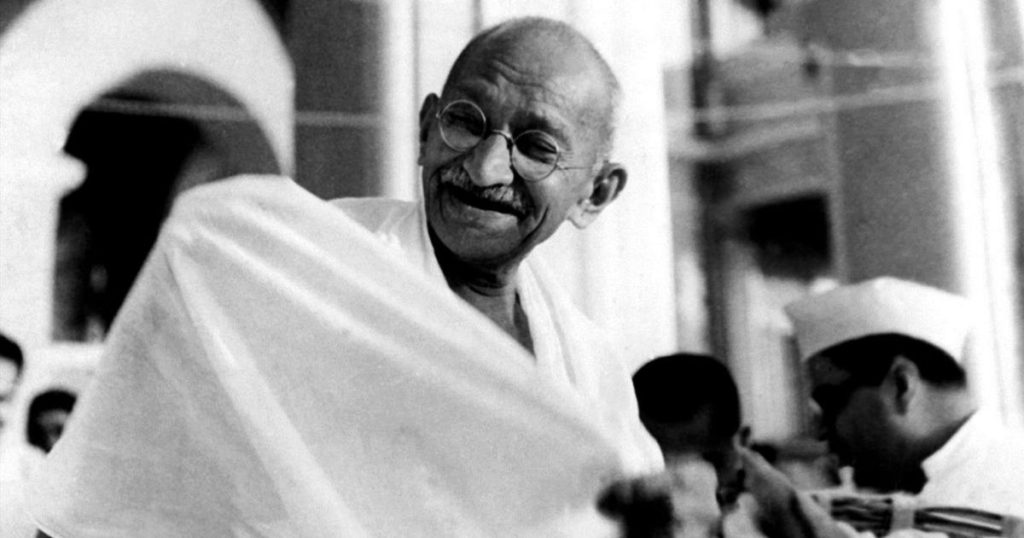

Freedom of speech and expression is an essential dimension of political freedom according to Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi. As he put it:

“We must first make good the right of free speech and free association before we can make any further progress towards our goal. […] We must defend these elementary rights with our lives. Liberty of speech means that it is unassailed even when the speech hurts; liberty of the press can be said to be truly respected only when the press can comment in the severest terms upon and even misrepresent matters…. Freedom of association is truly respected when assemblies of people can discuss even revolutionary projects.

“Civil liberties consistent with the observance of non-violence are the first step towards Swaraj. It is the breath of political and social life. It is the foundation of freedom. There is no room there for dilution or compromise. It is the water of life.”

Gandhi did not just write eloquently about the freedom of speech and expression as an integral and key aspect of the idea of freedom but was prepared to go to jail in its defence. In opposition to the colonial regime, especially after the Rowlatt Bill was introduced and the Jallianwala Bagh massacre had been committed by General Dyer, there were strong condemnations by Gandhi of the injustice of the British action in his own paper.

In an article titled, Tampering with Loyalty in 1921, he noted:

“I shall not hesitate at the peril of being shot, to ask the Indian sepoy individually to leave his service and become a weaver. For has not the sepoy been used to hold India under subjection, has he not been used to murder innocent people at Jallianwala Bagh….has he not been used to subjugate the proud Arab of Mesopotamia. [..] The sepoy has been used more often as a hired assassin than as a soldier defending the liberty of the weak and helpless. [..]”

He went on to say:

“[..] sedition has become the creed of the Congress. Every non co-operator is pledged to preach disaffection towards the government established by law. Non- cooperation, though a religious and strictly moral movement, deliberately aims at the overthrowal of the government and is therefore legally seditious in terms of the Indian Penal Code.”

In an article called the Puzzle and its solution, he wrote:

“We are challenging the might of this government because we consider its activity to be wholly evil. We want to overthrow the government. We want to compel its submission to the peoples’ will. We desire to show that the government exists to serve the people, not the people the government.

“Free life under the government has become intolerable, for the price exacted for the retention of freedom is unconscionably great. Whether we are one or many, we must refuse to purchase freedom at the cost of our self respect or our cherished convictions.”

The British responded to this criticism of their policy by charging Gandhi with the offence of sedition as defined in section 124-A of the Indian Penal Code. Gandhi was tried under section 124-A of the IPC on the charge of “exciting disaffection towards the government established by law in India”.

When Gandhi was arrested and produced before the court, instead of entering a plea of “not guilty”, he pleaded guilty and went on to make a statement which put the entire colonial system on trial. After indicting the government for the Rowlatt Act, the Jallianwala Bagh massacre and colonial economic policy which had impoverished millions, he put forward a staunch defence of the freedom of speech and expression:

“Section 124-A under which I am happily charged is perhaps the prince among the political sections of the Indian Penal Code designed to suppress the liberty of the citizen. Affection cannot be manufactured or regulated by law.

“If one has no affection for a person or system, one should be free to give the fullest expression to his disaffection, so long as he does not contemplate, promote or incite violence… I have no personal ill will against any single administrator; much less can I have any disaffection towards the King’s person. But I hold it to be a virtue to be disaffected towards a Government which in its totality had done more harm to India than any previous system.”

Though the judge convicted Gandhi, his statement indicates the impact Gandhi had upon him. J Broomfield noted:

“The law is no respecter of persons, nevertheless, it will be impossible to ignore the fact that you are in a different category from any person I have ever tried or am likely to try. It would be impossible to ignore the fact that, in the eyes of millions of your countrymen, you are a great patriot and a great leader.

“Even those who differ from you in politics look upon you as a man of high ideals and of noble and of even saintly life. I have to deal with you in one character only. It is not my duty and I do not presume to judge or criticise you in any other character. It is my duty to judge you as a man subject to the law, who by his own admission has broken the law and committed what to an ordinary man must appear to be grave offence against the state.”

As one of the contemporary accounts of the trial noted, “for a minute everybody wondered who was on trial. Whether Mahatma Gandhi before a British judge or whether the British government before God and humanity.”

The state and justice

In the sedition trial, Gandhi converted the charge against him of “causing disaffection” into a powerful statement on why “exciting disaffection” against the government was “the highest duty of the citizen”. In short, as Sudipta Kaviraj observes, the trial of the rebel was turned into something that appeared more like a trial of the state.

In this trial, what was contested most seriously was the link of the state to justice. As Gandhi demonstrates in eloquent prose, not only has the “law been prostituted to the exploiter” but even more grave is the “crime against humanity” of an economic policy that has succeeded in reducing people to “skeletons in villages” “as they sink to lifelessness”.

The concept of justice, both economic and political, is what is at stake and Gandhi demonstrated that the British state had forfeited its claim on his affection having completely violated its commitment to the Indian people.

What is clear from this in-depth engagement with Gandhi’s prosecution for sedition is that if we have a sense of history and a sense of respect for Gandhi, sedition should never have continued as an offence in the statute books.

In the light of the enactment of the Constitution, it should have died a natural death. It should have been abolished on the achievement of independence itself. Instead, the section continues to be in force and all governments have been happy to use it to prosecute opinion critical of itself.

(This is an extract from a short booklet: ‘Preamble: A Brief Introduction’, by Alternative Law Forum.)