In 1965, Ghana’s Prime Minister Kwame Nkrumah published a bold book, Neo-Colonialism: The Last Stage of Imperialism. In this book, Nkrumah documented in great detail the way in which European and North American multinational firms–in close collaboration with their governments–continued to smother the aspirations of the new nations of Africa. As an example, Nkrumah took up his own country, Ghana, which had been known by the colonial name ‘the Gold Coast’ until 1957.

One of the old colonial companies, Ashanti Goldfields (a British company) continued to make fabulous profits from the hard labour of Ghana’s gold miners; when Nkrumah’s government tried to raise the taxes on the firm, London newspapers screamed in outrage. Nkrumah wrote about how the gold fetched ‘merely token returns’ for the Ghanaian people, while Ashanti Goldfields offered vast dividends to its European shareholders. This, Nkrumah wrote, is neo-colonialism.

The United States government was furious about the ‘irresponsible extravagances’ in Nkrumah’s book and decided to punish him by refusing to allow $300 million in short-term aid to cover the costs of importing food. Nkrumah was unfazed. He decided to go to Hanoi (Vietnam) to meet with Ho Chi Minh. It was during this journey that the military in Ghana–egged on and assisted by the Central Intelligence Agency of the United States government and British intelligence (MI6)–seized power. Nkrumah’s attempt to build sovereignty and dignity for the Ghanaian people was side-lined.

The country’s wealth would continue to be siphoned off to multinational firms. The terrible injustice of imperialism, whose direct colonial form had been defeated when Ghana won independence under Nkrumah’s leadership in 1957, would morph into a new form, which Nkrumah called neo-colonialism. Neo-colonialism, he wrote in his 1965 book, ‘means power without responsibility and for those who suffer it, it means exploitation without redress’. This formula remains intact today.

The concept of ‘imperialism’ is treated as if it were anachronistic, no longer useful to explain the situation in our world. What other concept would help us to understand why both the private and public sector external debt of developing countries has increased over the past decade, and why this debt–now over $11 trillion–cannot be paid by countries with resources of great value? The resources in the Democratic Republic of the Congo alone are estimated to be worth at least $24 trillion; meanwhile, despite Congo having half of Africa’s water resources and forests, 51 million of the country’s residents remain without access to potable water–a result of the structural underdevelopment of Africa. An UNCTAD report from earlier this year estimated that the debt servicing payments for 2020-2021 would be between $2.7 trillion and $3.4 trillion (another estimate shows the upper limit at $3.9 trillion, of which about $3.5 trillion is for principal payments). No suspension or cancellation is on the cards because it is through instruments such as debt that governments are held in line and wealth is siphoned off to enrich multinational corporations and wealthy bondholders.

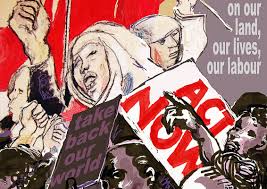

The Simon Bolivar Institute and Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research, launched a global process known as the International Week of Anti-Imperialist Struggle, which began on October 5 and ends on October 10 with a festival of anti-imperialism.

The International Week of Anti-Imperialist Struggle released a Manifesto of the Future, which we have included below:

Manifesto of the Future

Our humanity is threatened by an invisible virus that spreads rapidly; but we have long been challenged by other viruses, such as unemployment, hunger, racism, patriarchy, inequality, and war. These viruses manifest themselves differently in different parts of the world and sharply attack the lives of workers, peasants, and all of those who experience the impact of social inequality. Meanwhile, there is a minority of people that profit from the devastation.

The capitalist system has no answers to these crises; its policies are hollow. Rather than find a way to house us and feed us, the capitalists build vast machineries of destruction: police forces and militaries that suffocate the life out of the working class inside the rich nations and of the working class and the peasantry in the poorer nations. If a poorer country tries to stand upright, seeking to exercise its sovereignty, a full arsenal of power is used against it: financial, diplomatic, and military power. They dominate us with weapons, but also with ideas; they try to convince us that their views are the correct views.

The managers of the capitalist system are quick to unholster their guns and point them at distant adversaries, drive their tanks into our lands and occupy our homes, tear up nature and destroy our world; it is easier for them to provoke war than to fill the bellies of human beings with food. They would rather inflame people with racism and jingoism than to manage the fact that a broken system has come to rely more and more on the unacknowledged care labour of women, more and more on the harsh working conditions imposed on miners and factory workers.

The planet is on fire, the viruses are on the march, hunger stalks the land, and yet, even in this mess, we–the vast majority of the people on the planet–have not given up on the possibility of a future. We hope for something better than this, a world beyond profit and privilege, a world beyond capitalism and imperialism, a world singing the song of humanity. Our hearts are bigger than their guns; our love and our struggle will overcome their greed and indifference.

Many seeds are being planted by our movements. We need to water them, to tend to them, to make sure that they bloom. We will build a future that cherishes life rather than profit, a future of fellowship amongst peoples rather than racist wars, a future in which social hierarchies are abolished, and in which we enjoy mutual dignity.

Only when it is dark enough can you see the stars. It is now dark enough.

(Vijay Prashad is an Indian historian, editor and journalist. He is the director of Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research, an international, movement-driven institution that carries out empirically based research guided by political movements. Article courtesy: Tricontinental.)