Siddharth Varadarajan

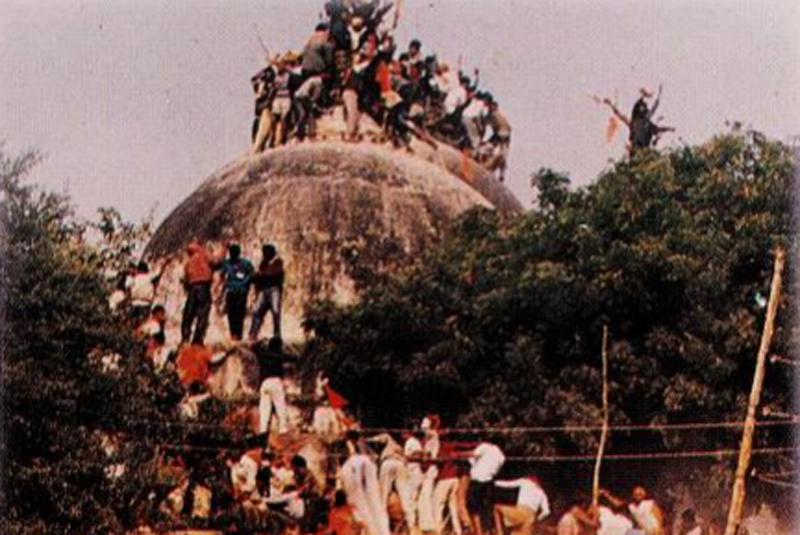

The Supreme Court’s verdict in the Ayodhya matter has settled the ‘title suit’ in favour of the main Hindu plaintiff—essentially the Vishwa Hindu Parishad—but it is clear that there is much more at stake for the country than the ownership of 2.77 acres of land on which a mosque stood for 470 years until it was demolished in an act of political vandalism unparalleled in the modern world.

The Supreme Court has undone some of the dangerous ‘faith-based’ logic of the high court and acknowledged the manner in which Ram idols were planted in the mosque was illegal and that the mosque’s demolition in 1992 was “an egregious violation of the rule of law”. Yet, the forces responsible for the demolition now find themselves in legal possession of the land. The site will be managed by a trust that the government will set up. And the government and ruling party have in their ranks individuals who have actually been chargesheeted for conspiring to demolish the mosque.

For more than a quarter of a century, ‘Ayodhya’ has served as a metaphor for the politics of revanchism—one which combines the deployment of a manufactured mythology around the figure of Rama, with mob violence, majoritarianism and a spectacular contempt for the rule of law.

The aim of this politics is to upend the republic with its premise of equality for all citizens and replace it with a system in which India’s religious minorities, to begin with, and then other marginalised sections of the population, are forced to live in perpetual insecurity.

If India’s democratic institutions had been robust, the demolition of the Babri Masjid on December 6, 1992 should have permanently ended this politics instead of merely marking the end of its first phase. Today, that politics has reached a new high water mark, presumably not its final one given the fillip a large section of the national media and now the Supreme Court have given it. Armed with the court’s imprimatur, the Sangh parivar will do its best to erase the taint of mob justice—which has been the strength but also the weakness of its movement. In August, BJP leaders boasted of how they had used Article 370 to kill Article 370. Now they hope to use law to kill justice.

We can pretend all we like that the Supreme Court was only adjudicating a civil dispute. In reality, there was nothing ‘civil’ about what a judge on the bench had called “one of the most important cases in the world”. The dispute cannot be divorced from the politics which has driven it.

The title suit in the Babri Masjid matter has been going on in one form or the other since 1949, mainly in the local courts of Faizabad, where Ayodhya is located. It took on national salience in the 1980s, thanks to the cynical politics of Lal Krishna Advani, Atal Bihari Vajpayee, Rajiv Gandhi and now forgotten villains like Vir Bahadur Singh and Arun Nehru.

BJP leaders conspired to demolish the mosque on December 6, 1992 and a Congress prime minister, Narasimha Rao, allowed them to get away with the crime. So did the Supreme Court judges of the day. Twenty-seven years later, the demolition case continues to linger. Even when all the evidence is recorded and arguments made, the outcome is uncertain since it is no secret that the prosecuting agency—the Central Bureau of Investigation—has wilfully dropped the ball.

Justice S.A. Bobde was right in observing in his interview to India Today—shortly after being named as the next Chief Justice of India—that there have been governments of all political persuasions in power at the Centre since the Ayodhya case first emerged in 1949. Yet the fact that the case ended up being fast-tracked at a time when the party in power today is one which openly asserts its partisanship on Ayodhya should be reason enough to worry us about happens next to the Republic. We already have a draft citizenship law which explicitly excludes Muslim refugees. A law has been passed that criminalises the abandonment of wives by Muslim men but not men of other religions. It is not a coincidence that the only part of India where the constitutional protections of liberty and free speech do not apply is a Muslim majority region, Kashmir.

Possible scenarios

While legal analysts had expected the five-judge bench to deliver a nuanced verdict that would not lend itself to shrill triumphalism by either side to the dispute, the clarity of the court’s ruling in favour of the temple will boost the morale of the Sangh parivar.

The fact that the ruling party—and hence the government—is committed to the construction of a Ram temple at the site of the Babri Masjid means the path is now clear for speedy implementation of the project. The court has asked for the government to constitute a board but apart from insisting on the inclusion of a representative of the Nirmohi Akhara—the third claimant to the title suit—it does not appear to have even sought the exclusion of individuals and organisations implicated in the 1992 demolition.

Even before the verdict, when there was a chance that court might uphold the Sunni Waqf Board’s claim, there was never any question of the Babri Masjid being rebuilt at the same site. Had they won, there would have been enormous pressure on the plaintiffs to give up their claim to the land. Indeed, in the fag hours of the Supreme Court hearings, the Waqf board chairman signed on to a controversial ‘mediation’ proposal under which he consented to the withdrawal of the appeal against the high court judgment in exchange for assurances that no other Muslim places of worship would be taken over thereafter. The other Muslim plaintiffs immediately cried foul. The fact that the main ‘Hindu’ plaintiffs—essentially the Vishwa Hindu Parishad—were not even prepared to sign on to such an assurance is a sure sign that this “most important case in the world” will likely be followed by others.

The Supreme Court has asked the government to allocate five acres for the construction of a mosque at a suitable place in Ayodhya, forgetting that the case’s significance was not about the availability of a mosque but whether it is permissible for anyone in India to use violence to dispossess a person or a community. Sadly, that question now appears to have been answered, implicitly, in the affirmative. Worse, the dispossession is acknowledged and ‘compensated’ with five acres elsewhere but those who did the dispossessing are still allowed to enjoy the benefits of their crime.

Bizarrely, the court has declared that while there was some evidence of Hindus worshipping at the disputed site, there is no documentary evidence of namaz prior to 1857 so hence by the “balance of probabilities” it is giving the land to the Hindu side. It should be readily apparent that this logic can also be applied to other mosques which the Hindutva organisations claim. Once the Ayodhya temple has been milked of all political mileage, the Sangh will up the ante elsewhere.

None of this should surprise us since we were never dealing with a civil dispute between litigants operating on a level playing field but a naked power play. One in which the political agenda of the ‘cultural’ Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh is not hidden and the biases of the Uttar Pradesh and Central governments are on open display. That is also why the Supreme Court’s insistence on mediation was so misplaced.

Fate of criminal case

Although the apex court chose to prioritise the title suit, fast tracking it to conclusion, it is not clear how the bench intends to firewall the demolition case from its verdict on the ‘property dispute’.

In his interview to India Today, Justice Bobde denied the court was attempting to legislate on matters of faith. He agreed with the suggestion that it is a “title dispute” but added: “The only thing is, what is the character of that structure, that is one of the issues. But even that structure doesn’t exist any more.”

Shouldn’t one of the issues then also have been why “that structure”—i.e. the Babri Masjid—“doesn’t exist any more”?

The main beneficiaries of the Supreme Court’s verdict on Saturday are organically linked to the main accused in the crime of demolishing the mosque. If the Ayodhya case is really one of the most important cases in the world, it is so because of the violence it is associated with. Can this case really be settled, then, without punishing the leaders responsible for that violence?

The five-judge bench represented an impressive array of judicial wisdom. Sadly, their judgment offers no pointers on this fundamental question.

(Siddharth Varadarajan is journalist, political analyst and academic. He is a Founding Editor of The Wire. He was earlier the Editor of The Hindu.)