Although there is no single term used by Dalits to identify their communities, the word ‘Dalit’ is well-established in scholarship and other writings.

Historically, the word ‘Dalit’ was chosen by some members of caste communities of Untouchables within a social and political context of equality, justice, and empowerment. Certainly, terms are not free floating and emerge in particular conjunctures: historical, social, political, ideological, and cultural as I have shown in my research and writing on the politics and history of Dalits in Maharashtra.

The varied names have resulted in many contestations and problems.

Time and again, members of Dalit communities have wrangled with these questions. Many of them do not want to use the word because a very small minority self-identify as Dalit, and many think that times have changed and they are not ‘Dalit’, that is, oppressed and broken anymore. In their eyes, Dalit is a derogatory term, just like ‘Untouchable’, ‘Mahar’, and ‘Chambhar’.

In 2018, some Dalits also petitioned to the Supreme Court of India to ban the word ‘Dalit’ and instead replace it with ‘Scheduled Caste.’ However, the Supreme Court rejected the Union government’s circular. The word continues to be contested.

The scholar, Christian Lee Novetzke in a recent article unraveled the first usage of the word by the revolutionary activist Savitribai Phule while referring to Mahars in 1869.

Dr B.R. Ambedkar used different terms to address the community: ‘Untouchables’, ‘Depressed Classes’, and ‘Boycotted community’. Although he rarely used the term ‘Dalit’, he and his co-associates certainly used it. The published speeches, writings, and pamphlets provide some evidences from the 1930s and 1940s on the usage of the word in the Marathi language that I have translated into English.

The Marathi version of the report of the All India Depressed Classes Congress held in Nagpur in August 1930, mentions the significance of the ‘Dalit Congress Meeting.’

Importance of Dalit Congress Meeting

The 1930 All India Dalit Congress Parishad is significant in Dalit community’s political movement of empowerment and liberation. First, this was the first meeting of the Dalit Congress to bring together the Untouchables of India. […] An All-India organisation of Dalit classes was founded. […] In conclusion, the Dalit Congress has led the way for liberation of the Bahiskrit [Boycotted] community deprived of manuski [human dignity].

It is noteworthy that the English and Marathi versions of this report illuminate the simultaneous use of a range of words: ‘Depressed Classes’, ‘Asprushya’ (Untouchable), ‘Bahiskrut’ (Boycotted), and ‘Dalit’.

Ambedkar presided over the meeting on August 8, 1930. In his speech, he clarified the focus of the meeting: “Dalit classes’ perspective on the question of India’s independence.”

He said:

“Will Indians be able to create an autonomous and united community? This question looms on the horizon of India. We have gathered here to assess the decisions of Dalit classes regarding this question. This question has created tremors not only in India but in the British empire and the world. The answer to this question depends to a large extent on our views. I think, you should not take this question casually. You should think of the pros and cons without any fear.”

Ambedkar emphasised the centrality of Dalit classes to the independence of the Indian nation, and moreover he wanted them to think, weigh the positives and negatives, and make an informed decision without fearing the dominant and privileged majoritarian population. To Ambedkar, basic human rights and adequate representation of the vulnerable minority, that is, ‘Dalits’, was significant to carve out the Indian nation.

Further, Ambedkar also shed light on the working of the Simon Commission.

Dalit Classes and Simon Commission

There is no doubt that the Simon Commission has sympathetically thought about protecting Dalit classes. Although it is not a complete picture the Commission has tried to understand the problems of Dalit classes. […] We should admit that the Simon Commission has tried to understand Dalit classes and their protection more than Montford Report.

Yet, Ambedkar argued that the Simon Commission’s work on the process of representing Dalits and numbers of Dalit representatives they mentioned was deplorable. As a result, Ambedkar concluded that Dalits must become self-reliant and fight for political power.

Upliftment, Improvement and Progress of Dalits

Gentlemen! We should gain political power, I have told you about this endlessly. However, I have also told you that not all problems of Dalit classes can be resolved by political power alone. Their liberation is in social improvement and progress. Dalit classes should abandon bad traditions and practices.

Ambedkar concluded his speech with a multi-pronged agenda for Dalit empowerment and liberation: social, educational, political, and ideological. Education, energetic activism, and enthusiastic organizing were/are important for Dalits seeking political power. He wanted Dalits to be fearless citizens underlining their basic human rights similar to the touchables.

Time and again, Ambedkar emphasised that “political power was a means to achieve all round social uplift, improvement, and progress” for Dalits.

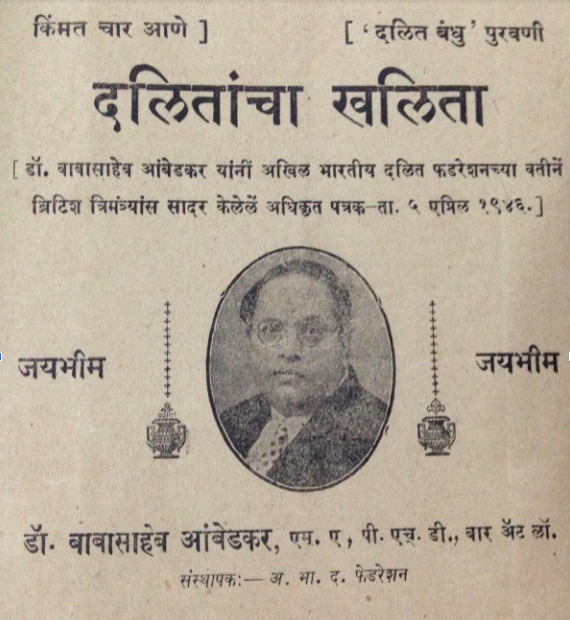

On April 5, 1946, on behalf of the All India Dalit Federation (AIDF), Ambedkar presented to the British the below Dalit khalita (petition) focusing on the all-round development of Dalits. V. N. Shivraj was the president. P.N. Rajbhoj, a Chambhar from Ghorpade Peth, Pune was the general secretary of the AIDF. Dadasaheb Gaikwad, a Mahar, represented the Bombay province. Shantabai Dani, a Mahar woman, represented women.

On April 4, 1946, at a meeting of the AIDF in Delhi, Ambedkar advised AIDF members to cut caste cords, remain united, and organise on deeper levels, especially through villages. He argued, “In this emergent situation, Untouchables should remain alert regarding their future and work on the success of AIDF. AIDF at provincial and district level should spread the message and work in a disciplined manner.”

Members of AIDF entrusted full rights with Ambedkar to negotiate with the British as well as future politics for Dalits in independent India.

The word ‘Dalit’ is inseparable from its social-political function and it effectively facilitated political action for Dalits. ‘Dalit’ has the force to capture the existential plight of the underrepresented, illuminate the revolutionary potential of the underserved, and connect with marginalised communities of the world full of resilience, empathy, and love.

(Shailaja Paik teaches at the University of Cincinnati. Courtesy: The Wire.)