A crucial argument for the incessantly promoted idea that capitalism will be with us for a long time to come is the idea of inertia in human understanding. Ideas are stubbornly persistent and can only be changed over long periods of time. Slow evolutionary change is the best we can hope for, and the prospects even for that are uncertain and fragile.

If the above were true, then there would have been no revolutions in history. That is quite obviously not the case. Consciousness can change rapidly. It does so exceptionally and under rare circumstances during periods of social upheaval. Yes, not everyday occurrences. But they do happen. “There are decades where nothing happens, and there are weeks where decades happen,” Lenin famously said.

We need not lean on Lenin. A survey of history need not be comprehensive to find examples of dramatic changes in consciousness, even if we exclude, for purposes of this discussion, national movements of liberation from colonialism, which generally didn’t meaningfully change social relations.

France alone offers us two examples: The French Revolution and the Paris Commune. That working people didn’t obtain what they wanted, the bourgeoisie were in a position to gain an upper hand due to material conditions and that a monarchal restoration would later occur doesn’t require us to deem the events of 1789 to 1793 a failure. The dramatic insertion into history of the popular masses is what we can center here, and it can’t be argued there wasn’t an overturning of a rotten ancien régime. Louis XIV’s boast that he was the state (“L’état, c’est moi”) was reality given his absolute powers. Peasants were subject to starvation during poor harvests, and were subject to being strapped to a plow like an ox to pull a cart or forced to spend nights swishing a stick in a pond to keep the frogs from croaking so the local lord wouldn’t have his sleep disturbed. Town laborers worked 16-hour days and wages were codified as “not exceed[ing] the very lowest level necessary for his maintenance and reproduction.” The church provided the ideology to cement feudal relations in place, telling them all this was God’s will.

These conditions were endured, until they weren’t. Rebellions were hardly unknown across feudal Europe, but had tended to be isolated affairs. French peasants and laborers had been acquiescent to their miserable conditions, or so it seemed. As discontent among social classes mounted, the first demonstrations broke out in 1787. Organization and the education movements provide put people in motion. In only two years, the movement went from issuing petitions asking for reforms to overthrowing the monarchy.

There are also the revolutions of 1848 across Europe. It is true these would falter one after another as traditional authorities, mostly monarchal and military, would reassert themselves. But these upheavals could never have occurred without peasants and proletarians ceasing to continue total deference to elites and institutions. Masses were in motion, but the ideas, although temporarily crushed, survived and began to be implemented within decades.

Societies across Europe were rigid class dictatorships, with the elites of their countries horrified at the very idea that common people might be given some say in how they were ruled. Incontestable violence was the frequent response to any stepping out of line. And while demands like a constitution wouldn’t seem at all radical today, they were in 1848 — granting them would have meant at least some rights for common people codified in law. The revolutions were failures in terms of immediate results, but the ideas raised would become common sense not long into the future.

When implemented, these changes were not revolutionary, it is true, as national elites found they could accommodate such demands and not have their rule challenged. But millions previously resigned to bowing their heads and accepting their bitter lot learned to speak up, to organize, to struggle and to imagine that a better world could be brought into being. As Priscilla Robertson wrote in her marvelous account, Revolutions of 1848: A Social History, “Most of what the men of 1848 fought for was brought about within a quarter of a century, and the men who accomplished it were most of them specific enemies of the 1848 movement.”

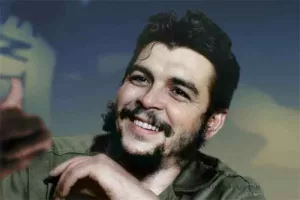

An early demonstration in the Paris Commune

No account of 19th century uprisings could possibly omit the Paris Commune, the first socialist revolution in history. Consciousness wasn’t simply profoundly changed in 1871; the ideas of that new consciousness were put in action. The Paris Commune enacted several progressive laws — banning exploitative night work for bakers, suspending the collection of debts incurred during the siege, separating church from state, providing free education for all children, handing over abandoned workshops to cooperatives of workers who would restart production, and abolishing conscription into the army. Commune officials were subject to instant recall by voters and were paid the average wage of a worker.

The Commune would be drowned in blood. But we can readily see the difference between the vision of a better world and the ruthless violence used to suppress any attempt at putting such a vision into practice. A National Guard commander freed captured French army officers in a spirit of “comradeship,” to the point where a top army commander was let go in exchange for a promise that the commander would henceforth be neutral — a promise that was swiftly broken. The Communards’ magnanimity was repaid with a horrific bloodbath. An estimated 30,000 Parisians were massacred by the marauding French army in one week. Another 40,000 were held in prisons, and many of these were exiled to a remote South Pacific island where they became forced laborers on starvation diets, eventually barred from fishing in the sea or to forage for food, and routinely subjected to torture. The restored government exerted itself to deny any political or moral content to the Communards’ actions, instead treating them as the worst common criminals as part of what developed into a de facto “social cleansing” of Paris; the French official overseeing the deportations, in his public statements, directly linked socialist politics with chronic petty crime.

The very peacefulness of the Communards was a sharp divergence from ordinary governing practices. Only a people who had rapidly gained new and radical understandings of how society might be organized could have created such a government. Those ideas aren’t extinguished when bloodily suppressed, but remain alive for the next generations.

There are no shortages of examples to be drawn from the 20th century. Start with perhaps the most obvious example, Russia in 1917. Russia was a vast sea of illiterate peasants yoked to the land and held in bondage through superstition and backward social institutions; ruled by a tsar whose every word was incontestable law and backed by exiles, whippings and executions. Agitation by organizers in social democratic parties had made some headway, exemplified in the soviets of 1905, but even that was cut off when Russians accepted their country’s participation in World War I the same as the peoples of other countries. Yet three years later, all of Russia was in motion. Russians refused to accept any longer the brutality and backwardness forced upon them. More than 300,000 Petrograd workers took part in strikes during the seven weeks immediately preceding the February Revolution and mutinies spread throughout the army.

And it is not often remembered that women workers touched off the February Revolution — yet another overturning of social relations that required new consciousness. Women textile workers in Petrograd walked out on International Women’s Day, walked to nearby metal factories, told the men there to join them on strike, and both groups inspired workers in other factories to walk out. In two days, a general strike was underway in Petrograd, with demonstrators shouting anti-war and anti-monarchy slogans. And what could the October Revolution be other than a mass demonstration of changed thinking? Soldiers and sailors disarmed their officers and turned the military’s orientation 180 degrees, and that enabled civilians to disarm the police. The October Revolution took place in the capital city with the city’s residents filling the streets, occupying strategic buildings and electrifying the world with their cascade of motion and unity of purpose, backed across the country by workers, peasants, soldiers and sailors asserting their collective will. That was no “secret coup” as pro-capitalist historians consistently but falsely assert.

From object to subject in Nicaragua and Chile

And there is Nicaragua, the pre-revolutionary history of which was a history of exploitation. There would not have been a Sandinista Revolution coming to power in 1979 if it weren’t for the willingness of activists to adapt ideas developed elsewhere to Nicaraguan conditions and to draw upon local conditions and realities, blending them with the writings of 1930s liberator Augusto Sandino. In just a handful of years, a country at the mercy of the gigantic neighbor to the north accustomed to treating everything south of the Rio Grande as its “backyard” and under the whip of a brutal local family dictatorship maintained through copious amounts of torture and violence overturned both. A mass change in consciousness was created, without which Nicaraguans in huge numbers wouldn’t have had the fortitude to overthrow the Somoza family, defy the United States and create a dramatically different society and governing structure.

The Sandinistas also provided an important lesson, one equally applicable to advanced capitalist countries as underdeveloped ones. Although no theory can be transplanted whole to another place or time, there was an explicit acknowledgement, which was acted upon, that workers are not only blue-collar factory employees, but are also white-collar and other types of employees in a variety of settings, in offices and service positions, among others. Any revolution that seriously attempts to transcend capitalism, which means eliminating the immense power of the capitalist elite, has to include all these varieties of working people if it is to succeed in the 21st century. Mass consciousness would change so thoroughly that the Sandinistas had to go ahead with an insurrection sooner than they had planned because everyday people were moving forward so fast.

A different type of transformation was attempted in Chile, where the movement toward socialism was voted in but soon had profound effects. So profound was the beginnings of that transformation that frightened capitalists used fascistic levels of violence to turn back the clock. But, given the past couple of years of movement work in Chile, culminating in a Left-led writing of a new constitution to replace the Pinochet constitution, the ideas of the early 1970s have not been buried forever. Following the election of Salvador Allende, Chilean workers rapidly learned to manage their enterprises and take control of their lives.

A representative example would be the Yarur textile factory, the enterprise focused on by Peter Winn in his indispensable study of the Allende years, Weavers of Revolution. Those workers had to overcome fear and memories of past repressions before they could band together to improve their conditions. Dr. Winn painted a vivid picture of the Yarur facility at the time of President Allende’s victory: “A passive and isolated work force, carefully selected and socialized, purged of suspected elements, disciplined by the Taylor System, and represented by a moribund company union; a paternalistic patrón who dispensed favors and largesse at his pleasure in return for unconditional loyalty, but who punished disloyalty with righteous anger; a network of informers that covered both the work sections and the company housing; and a structure of scaled punishments for transgressions against the patrón or his social politics that ranged from a verbal warning to summary dismissal and blacklisting.”

Yet in a matter of months, this once-cowed workforce went from clandestine work to create an independent union seeking merely better wages and working conditions to openly making demands such as firing hated foremen and moving to “free the factory.” Dr. Winn wrote, “The roots of revolution might be present, along with the justification for rebellion, but a precondition for this revolution from below was a dramatic change in the workers’ view of themselves, their capacity and power, as well as their perception that for once the state would support them in any showdown between capital and labor.” This leap in consciousness was replicated across the country.

President Allende’s Popular Unity government achieved strong results in its first year. Unemployment was halved, inflation was reduced, the labor share of income increased from 55 percent to 66 percent and not only did the country see strong industrial growth, the growth came from production of basic goods such as food and clothing in contrast to prior years when growth was based on durable goods such as appliances and automobiles. Perhaps the most basic measure of the improvement was that the poor could now afford to eat meat and buy clothes. What might have been created if the U.S. government and Chile’s capitalists hadn’t crushed it?

What might have been created without interference?

Not all the revolutions discussed were successful, and you might disagree with the direction that some of those that were successful took. There can be no guarantees for the future. The point here isn’t that a change in thinking among enough people that a revolutionary situation arises, and is acted upon, guarantees success. Overwhelming power was brought to bear on the revolutions that failed, and overwhelming power was brought to bear on those that did succeed, distorting the results. We can not know what might have been accomplished had revolutionary governments had the space and time to develop peacefully, including in many other examples that could have been cited in this brief survey.

We might also consider non-revolutionary changes on a national level. To cite just one example, consider Germany. Having unified across the 19th century mostly due to the expansionary tendencies of Prussia, and finally achieving unification through Prussia’s lightning victories over Austria in 1866 and France in 1870, Prussian militarism was a dominant ideology in the young country with the military holding strong sway. Although the rise of Hitler had multiple causes, the militaristic ultra-nationalism that was in large part a holdover from Prussia accommodated itself well to Nazi government; indeed, supported it before the taking of power.

But after World War II, those tendencies rapidly receded. Would anybody today see Germans as a nation of Prussian militarists bent on expansion? German national culture is very different today. Ideas changed sharply and rapidly. Yes, under the impact of a second devastating defeat in a continent-wide war. But the potentiality of such a change had to have been there, and we can point to the wide interwar support of the Social Democratic and Communist parties, and the rise of social democracy before the first world war. The treachery of the Social Democrats and sectarianism of the Communists, and their destruction during the Nazi régime, undermined the chances of more profound change (while acknowledging Allied and particularly U.S. impositions from 1945 that limited change in West Germany to capitalism under U.S. suzerainty and Soviet compulsion that molded East Germany).

Changes in consciousness and belief systems don’t need decades, much less centuries, to change. Such changes don’t, and won’t, happen without enormous organizing, which includes gaining the ability to disseminate materials exposing and contradicting standard ideology and presenting alternatives that speak to people’s lives and goals, most importantly conceivable ideas and concepts that lead to a better world. A better world will come about through the everyday work of organizing and campaigning, not through blueprints. Some of the bricks of today will inevitably be used in building the institutions of tomorrow but those bricks can be arranged differently.

What is radical one day is everyday common sense another day, and the time span between those two days is not necessarily distant. The idea that one family was granted the right to rule in perpetuity, the idea that a human being could own another human being, the idea that everyone was born into a particular class and could never leave it, have passed into history. Why shouldn’t the idea that only a minuscule number of people have the ability to manage enterprises and should therefore be paid hundreds of times more than those whose work produces the profits also pass into history?

The idea that capitalism doesn’t work for most people, that a better world is possible, has animated millions and some of those millions have tried to put those ideas into practice. The ability to see through capitalist propaganda arose quickly — the peoples mentioned throughout this article didn’t need centuries. Popular opinion changed dramatically and rapidly.

That shifts in mass consciousness with revolutionary potential have rarely taken place in the world’s advanced capitalist countries does not mean they can’t happen in the future. What forms any such uprisings might take can’t be known, and could take different forms than previously seen. Repressive rule, whether through monarchs, armed force or economics, is not forever. Nothing of human creation is forever. Capitalism isn’t an exception and will be history when enough people decide to make it so. Organize!

(Pete Dolack writes the Systemic Disorder blog and has been an activist with several groups. Article courtesy: CounterPunch.)