W.T. Whitney, Jr.

Like the sun, the US blockade of Cuba will not disappear soon. Unlike the sun, the blockade seems mostly forgotten in US government circles and beyond. It’s persisted basically unchanged for almost 60 years. What follows is about change.

What doesn’t change is abuse handed out to anyone in public life who says nice things about Cuba. Recently presidential candidate Bernie Sanders tried to ward off attacks as he praised Cuba’s 1961 literacy campaign. But labelling Cuba’s leadership as “authoritarian” didn’t work. Senators Rubio and Menendez and other politicians, Democratic and Republican alike, lashed out. Democratic leaders in Florida joined in, conveying the idea that at election time in Florida, Cuba matters.

Once more, on February 25, President Donald Trump authorised continuation of the blockade. He proclaimed a national emergency. Legislation passed in 1976 requires the president to periodically reconfirm the pressing nature of the Cuban emergency.

Regulations have long been in place that bar ships from entering US ports for six months after leaving off or taking on cargo in Cuba. The US Treasury Department has long penalised companies in third countries, or their affiliates anywhere, for marketing products in Cuba that contain even tiny US components. Foreign banks, insurance companies, and international agencies have long paid big fines if they deal with Cuba directly or handle US dollars in the course of someone else’s transactions with Cuba. Even now US travelers to the island risk fines for violating this or that blockade rule. Slight easing of blockade regulations under the Carter and Obama administrations was short-lived.

The heirs of families whose properties were nationalised in Cuba benefit now from a 2019 presidential decree allowing them to bring suit in US courts against individuals or companies anywhere who have used or profited from their former properties. The US government wants to frighten current or potential investors enough for them give up on enterprises in Cuba.

The US government has never strayed from cruel State Department recommendations in 1960 on how to defeat Cuba’s Revolution. They called for creating shortages and suffering severe enough to persuade desperate Cubans to rise up in rebellion. According to official sources in Havana, cumulative losses and shortages over the decades have deprived Cuba of $922.6 billion, adjusted for inflation. .

The US government is persistent too in its dedication to taking down other objectionable governments, as evidenced by regime change in Iran (1953), Guatemala (1954), Dominican Republic (1965), Chile (1973), Grenada (1983), Panama (1989), Nicaragua (1980s), Honduras (2009), and Bolivia (2019)—and by assaults on Venezuela.

Proponents of the blockade can choose among various rationales at their disposal: it solidifies the loyalty of right-wingers to this or that administration, expresses gratitude to Cuban–Americans for their political support, projects an image of serious state power, or might finish off the Cuban Revolution. Justifications like these, with long half-lives, require no new thinking; US policy-making on Cuba is on automatic pilot.

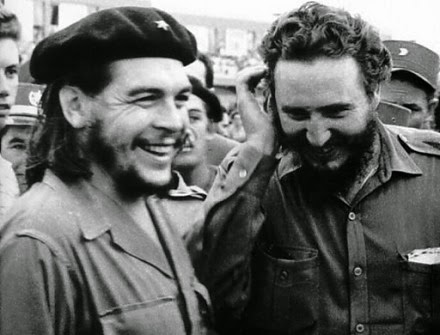

In Cuba it’s different. The revolutionary government has to respond to people’s needs, overcome the US blockade, and build a socialist society. Clearly, decision-making amidst conflict and challenges is taxing on planners and leaders at every level. They presumably strategise, study, listen, calculate, analyse, persuade, compromise, and more. This kind of effort, with rough edges, speaks to thought processes leading to change rather than to the status quo. In short, seeds of change germinate in soils rich with contradictions.

This is the context for Cubans who, following the lead of former President Fidel Castro, engage in what they call a battle of ideas. For instance, President Miguel Díaz–Canel, officials of the Ministry of Economics and Planning (MEP), and other government and Communist Party leaders met on February 24. They discussed economic planning under blockade conditions. Referring to the MEP as a “ministry of thought,” the President called for prioritisation of “administrative mechanisms over economics and finances,” a balancing of economic centralisation and decentralisation, planning that is “more open and less detailed,” and transparency in reporting “economic results, the good and the bad.”

Ethical and legal principles are asserted. On February 25 Chancellor Bruno Rodriguez presented Cuba’s case against the US government before the United Nations Council on Human Rights. He cited “non-conventional wars … violations of international law … rights to peace and free determination…. The selflessness of more than 400,000 Cuban health care workers that in 56 years have fulfilled missions in 164 nations.” He denounced “infringement by neoliberalism of economic, social, and cultural rights” and a “lack of will to confront climate change.”

José Martí, Cuba’s national hero, figures in political discourse. Recalling sentiments on Marti that students had communicated on his website, President Díaz–Canel on February 24 mentioned Enrique who had carried the Cuban Flag to the Summit of Pico Turquino, Cuba’s highest mountain, “solely to honour Martí.” For the President, Martí is the “most universal of Cubans.” It was Martí who, in preparing Cubans for their War of Independence of 1895–1898, famously advanced the idea of “With all, for the good of all.”

Cubans put ideas into practice. Argentinian observer Atilio Boron recently observed that that there are no destitute, homeless children in Cuban streets. They are in school and well cared for. There are no homeless people. All Cubans have access to health care and education at no personal cost. Schooling extends from kindergarten to graduate school and beyond. Boron highlights US deficiencies in these areas.

Ultimately, tension in Cuba stemming from conflicting realities stimulates innovative thinking that embraces change. It doesn’t lead to the consolidation of one or another set of existing realities. Instead it stimulates the formation of new ones. Along the way, goals are set out, among them: effective state planning, attention to the common good, and unity.

Vietnam had to fight for independence from France and resist American marauders. The experience foreshadowed the siege conditions Cuba has been saddled with. In both instances, strategising for the future played out within contexts of conflict and stress. Cuba’s goals parallel earlier ones realised in Vietnam.

Over three decades, the annual GDP for the Socialist Republic of Vietnam has averaged 6.5 percent (6.8 percent in 2019). Vietnam’s export income now ranks among the world’s top 25 nations. The nation’s poverty rate fell from 75 percent to nine percent, unemployment remains at 3–4 percent, and literacy rose to 93 percent. Life expectancy at birth is 72 years. The entire population enjoys access to free health care, education, and comprehensive social services.

It makes sense that a prepared and unified people attending to the good of all will be able to deal effectively with the current coronavirus pandemic. The odds are that Cuba’s response to the threat will be smoother than that of the United States. After all, Cuba’s health care system emphasises both preventative and curative care. It’s a public health system, no more, no less.

The US health care system reflects weak advocacy for preventative care and surrender to the market-based economy. The Harvard Health Policy Review headlined a 2018 article this way: “Increasing Mortality and Declining Health Status in the USA: Where is Public Health?”

(W. T. Whitney Jr. is a political journalist whose focus is on Latin America, health care, and anti-racism.)