In 2019, I spotted an infographic on Twitter that ranked a handful of countries by the number of weeks of paid maternity leave they mandated. It sought to make a case for paid maternity leave in the United States—where, according to the infographic, there was none. India occupied second spot, with 26 weeks, just behind the United Kingdom. What struck me was that even though the Maternity Entitlements Act benefits only women in formal employment in the organised sector—a very thin slice of Indian women—its provisions were being projected as a universal entitlement. In fact, the meagre entitlements for other Indian women—Rs 6,000 per child in cash from the government, under the National Food Security Act passed in 2013—were not operationalised until 2017.

That year, the government notified the Pradhan Mantri Matru Vandana Yojana to deliver on the promise of the NFSA. On the one hand, the Maternity Entitlements Act was amended to increase paid leave from 12 to 26 weeks for women in formal employment; on the other, the rights of women covered by the PMMVY were reduced—instead of providing Rs 6,000 per child, they would get only Rs 5,000 as a maternity benefit, over three cash instalments and for the first child only. For perspective, for someone in my kind of privileged employment, teaching at a public university, the analogous compensation for a full 26 weeks of maternity leave would be at least a hundred times that amount. Yet when the PMMVY was announced, one reaction from some privileged commentators was that it was a bad idea because the cash benefit would incentivise more births.

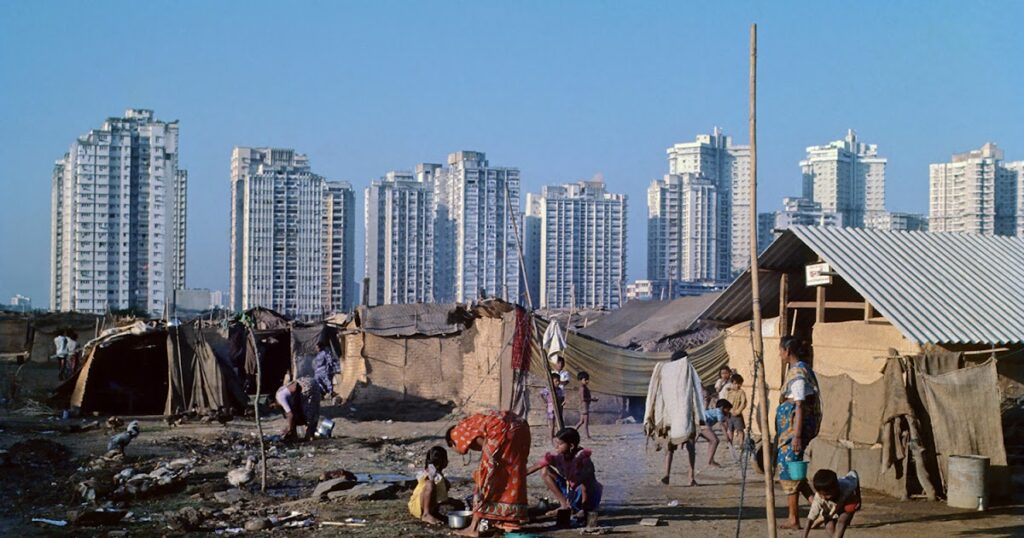

To be clear, the problem is not that some women in India enjoy world-class maternity benefits, but that the same level of benefits has been denied for so long, even resisted, as a universal right. What sort of society is able to provide more and more for the privileged but grudges every penny set aside for those in greater need? One answer is a society that expects a nanny state for the rich but wants the poor to be aatmanirbhar—self-reliant.

The contrast in maternity benefits illustrates a much broader pattern. Among economists, a widely used measure of inequality is the Gini coefficient, which quantifies disparities in incomes, wealth and expenditure. In India, that number has been steadily rising since the 1990s. There are also other indications that the country fares very poorly on equality. For instance, work by the French economists Thomas Piketty and Lucas Chancel shows that the top one percent in India have seen their total share of national income rise from six percent in 1980 to 22 percent now.

Such inequalities have become so routine in the country that they do not even invite a shrug of the shoulders. Take, for instance, corporate India’s reaction to the COVID-19 pandemic and resulting lockdowns. These dealt a triple blow: a humanitarian crisis and an economic catastrophe on top of the health emergency. The most vocal calls for government support came from the corporate sector—whether in the form of tax concessions or subsidised credit or relaxations of labour law. It justified its demands by claiming that it would be able to contribute to the revival of the economy—that is, not lay off employees—only if it received a helping hand.

This seemed to have the desired result. When the Modi government announced the “Aatmanirbhar Bharat” relief package, it promised aid measures worth ten percent of the country’s GDP. Yet, according to some estimates, the equivalent of merely one percent of GDP was dedicated to programmes that directly benefited the poor, such as subsidised food distribution, guaranteed rural employment and direct cash transfers. Once again, it was hard not to think of India as a nanny state for the rich that wants the poor to be aatmanirbhar.

Corporate houses begged for relief from the government yet simultaneously paid unimaginably high salaries to their CEOs. Since 2015, a Securities and Exchange Board of India rule has required that publicly traded companies disclose the compensation given to “key managerial personnel” vis-a-vis other employees. Specifically, they must report the median salary of employees—at which half of employees earn below the sum and half earn above it—and the remuneration paid to top management. The ratio of the median to the salary of the top-paid executive indicates the pay ratio, which measures inequality within the company. A pay ratio of 2 means that the executive makes twice as much as the median employee.

Pay-ratio data has not been widely used in India to understand inequality. In 2020, the economist Meghna Yadav and I compiled the latest pay ratios for private companies in the NIFTY 50 index (public-sector companies are exempted from such disclosures). The highest pay ratio was for Hero Motocorp, and stood at 1:752. The annual remuneration for Pawan Munjal, the company’s head, was Rs 84.6 crores—roughly $11 million. Even the lowest pay ratio—1:39, at Maruti Suzuki—was very high. The average of these pay ratios was 1:259.

Other countries have similar disclosure mandates. The Guardian reported in 2020 that the chief executives of the top 100 companies in the United Kingdom were paid the typical worker’s annual salary for every 33 hours of their time. In comparison, Munjal’s earnings for even half a day would exceed the annual pay of the median employee at Hero, going by the 2019–20 figures.

When the pandemic hit, at least some big private players were more willing to lay off employees or reduce their pay than to touch their top executives. For instance, Infosys reported “performance-based exits” and shed a reported 3,000 employees in the first quarter of 2020–21. The company’s highest-paid person exercised stock options worth Rs 17 crore in 2019–20 and also received the same amount in remuneration. The following year, that compensation, inclusive of stock options, increased to almost Rs 50 crore.

In India, the super-rich and the privileged—the top ten or 20 percent—get away lightly. Moreover, many of them believe they are “middle class.” I am often frustrated by many friends and colleagues referring to themselves as such. They are English-speaking, own one or more cars, they invest in stocks, their default mode of travel is by air, they have domestic help and sometimes holiday abroad. Their children study in schools where the annual fee roughly equals the country’s annual per capita income.

Contrast this with a rural resident I met in August 2021 on a field trip to Alwar, a relatively prosperous part of Rajasthan. He combines farm income with a salary as a private teacher. We talked about the lockdown, and he remarked that the middle class had suffered a lot. I asked him how he would define the middle class. His definition was far more modest than that of my friends: “A middle class person is someone who, if he gets work today, he will eat vegetables with his evening meal. Otherwise, he will have plain roti.”

These two contrasting conceptions of the middle class—from paying a lakh or more per year as school fees for one child to earning enough in a day to buy fresh vegetables for your evening meal—capture something important about our society today. Many of the well-heeled urbanites who consider themselves part of the middle class are, in fact, among the top 20 percent of Indians, if not the top one percent.

Over 2020 and 2021, suspecting that this misperception is widespread, I conducted a rudimentary test: I asked several hundred of my students at the Indian Institute of Technology Delhi and the Indian Institute of Management Ahmedabad what class they thought they belonged to, and also whether their family owned a car or had an air conditioner, an internet connection and a sewage connection at home. These seemingly middle-class comforts are actually enjoyed by a small minority in India: according to National Family Health Survey data from 2015–16, only a tenth of households reported owning a four-wheeler, one third had an air conditioner and merely one fifth had toilets linked to a sewer line. More than threefourths of the IIT and IIM students I surveyed had access to these facilities, yet almost ninety percent selfidentified as middle-class. Only ten percent self-identified correctly, as members of the upper class.

Less than a tenth of Indians are English speakers. The estimated number of Netflix subscribers in the country is merely two million, and of Amazon Prime subscribers ten million. By one estimate, there were 340 million Indian airline passengers in 2020—that’s roughly one fourth of Indians if each passenger were unique. If you use an e-wallet, you are among the 14 percent of urban Indians to do so, or among the 2.4 percent of rural residents. If you hold shares, you are among the two percent who own them.

The World Inequality Database has a tool where you can input your income or wealth to estimate where you sit on the income-distribution scale. Whenever I have asked people to try it, they have been surprised at how high on the scale they actually are. For context, my post-tax government salary alone puts me in the top five percent of Indians, and I would climb higher if I had other sources of income.

In spite of all the evidence, the rich cling to their “middle class” positioning. Why should it matter if people misconceive of themselves as middle-class rather than rich or super-rich? The “middle class” in India feels beleaguered, oppressed by the belief that while the entire burden of taxation falls on them (not true) they get nothing in return (also not true). They forget that their tax money is providing them the luxury of their sewage magically being taken away from their homes, roads that they can drive their cars on, traffic lights, street lighting, parks, museums and so on.

In discussions on inequality in India, there is often agreement that we must do something about it. Yet, when policy options are floated, we hit a wall. Given the options for raising revenues—say, through a wealth tax, vigorous taxation of property and so on—the resistance and lethargy can only be explained by the fact that most options affect the super-rich, whom India’s super-rich power elite would like to touch, if at all, only with a velvet glove. In this, the “middle class,” which aspires to be super-rich, aligns itself with them.

Several of India’s democratic institutions have been captured by the super-rich. For instance, the average wealth of those who contested the Lok Sabha elections in 2019 was 21 times the all-India average. Of them, those candidates who won the elections declared wealth greater than a hundred times the all-India average. Similar patterns are likely to apply to much of the Indian media, academia, bureaucracy and so on.

It is possible that we tolerate so much inequality because we do not see it; it is almost as if it is being carefully hidden from us. Years ago, a sympathetic business journalist was interviewing an economist colleague. The television crew spent nearly half an hour transforming the supposedly drab lobby of the Indian Social Institute into a snazzy-looking studio. While the economist described the dire situation with respect to food and nutrition in India, the crew stepped in to powder little drops of sweat that developed on the journalist’s forehead from the heat of the heavy lighting. It was not cool, it seemed, for a sweaty brow—let alone hungry or poorly nourished people—to be seen on television. I later shared my reaction with the journalist, who apologetically explained the difficulties they face in making space for such issues and the hoops they are compelled to jump through to make them palatable for their sheltered audience.

Such invisibility and lack of information hampers a social consensus for more substantive redistributive action.

Oddly enough, during the lockdown, social media managed to capture the enormity and poignancy of the inequality crisis. For the minuscule minority whose jobs and earnings remained safe throughout, the lockdowns were a blessing, even if a mixed one. They rediscovered old talents, developed new skills: baking, cooking, sketching, gardening and so on. Images of gourmet meals flooded social media. It was disconcerting to see these interspersed with images of exhausted, hungry and harassed workers and migrants, suddenly left stranded and taking desperate measures to try and get home.

The enormity of the migrant crisis meant that even television news had to pay attention to the suffering. But that fleeting moment, when mainstream media allowed audiences a glimpse of the condition of the majority of Indians, has passed. Perhaps in a moment of naivet, when the scale of the humanitarian crisis became apparent and got the attention it deserved, I wondered whether “middle class” India’s outpouring of concern would turn the tide in favour of people-oriented policies. It had happened before, after all.

After the Second World War, in several western European countries, a realisation dawned that bombs did not discriminate between the rich and the poor. Over the two decades following the war, these capitalist nations—in varying measures—embraced social democracy. They built impressive welfare systems that provided protection to all “from the cradle to the grave,” promoting their life chances through better healthcare and education.

The indications are that we have squandered our opportunity. The pandemic has been turned into a reason to close schools down in the name of protecting children, and then forget them. Even as everything else—air-conditioned cinema halls, malls, political rallies, religious gatherings—was back in action, schools remained shut. This was a huge setback to decades’ worth of effort for social mobility.

Similarly, in healthcare, instead of strengthening public health systems, we have let the private sector snatch the narrative, pushing fanciful ideas such as digital health IDs that will facilitate lucrative business opportunities in mining health data but do nothing to improve access to quality health care for all.

Demands to mobilise resources through a one-time wealth tax and increase public health expenditure have fallen on deaf ears.

“Either we all live in a decent world, or nobody does,” George Orwell once stated. His vision was for a society where solidarity and fairness are founding principles. Redistribution is an essential function of government—redistribution from the rich to the poor. Today, many governments—not just in India—resist or even prevent redistribution of resources to the poor. Questions of redistribution fall as much in the domain of economic policy as in the realm of democratic debate. We cannot blame failures on the economic front—say, a slowdown in the rate of GDP growth—for the inequality crisis we are faced with. That crisis points to a wider failure—both social and democratic.

(Reetika Khera is a development economist and teaches at the Indian Institute of Technology Delhi.

Courtesy: Caravan Magazine.)