Capitalist crises are neither predictable nor do they stem from a single cause. Instead, at least as I see it, the possibility of a crisis is always there but the causes and triggers are all historical and therefore multiple and varied.

Sometimes, crises in capitalism stem from difficulties in extracting more surplus from workers and a resulting fall in corporate profit rates; at other times, they are caused by the bursting of speculative bubbles and a run on funds within the financial sector; and, as seems to be the case this time around, many corporations relied on cheap money and extended their indebtedness way beyond their ability to pay in the event of an unexpected “shock” (like the novel coronavirus pandemic and, in the United States, by the Trump administration’s much-delayed response). In other words, capitalist crises don’t follow given laws and depend, instead, on the concrete circumstances.

But there is one thing capitalist crises all have in common: unemployment.

As readers can see in the chart above, every economic downturn (the shaded areas)—every recession or, as after 2007-08, depression—the official rate of unemployment has gone up.* Workers, millions of them, have been made “redundant” (to borrow the term from British English, workers who are deemed “superfluous” to maintaining or restoring profitability).

That’s because, under capitalism, workers have no right to a job (much less the right to participate in decisions about when and where jobs will be created or destroyed). Instead, they have to work hard to attempt to sell their ability to work—and they’re forced to do so to survive, because their ability to perform labor is only valuable on the market when it can be used to make profits for someone else.

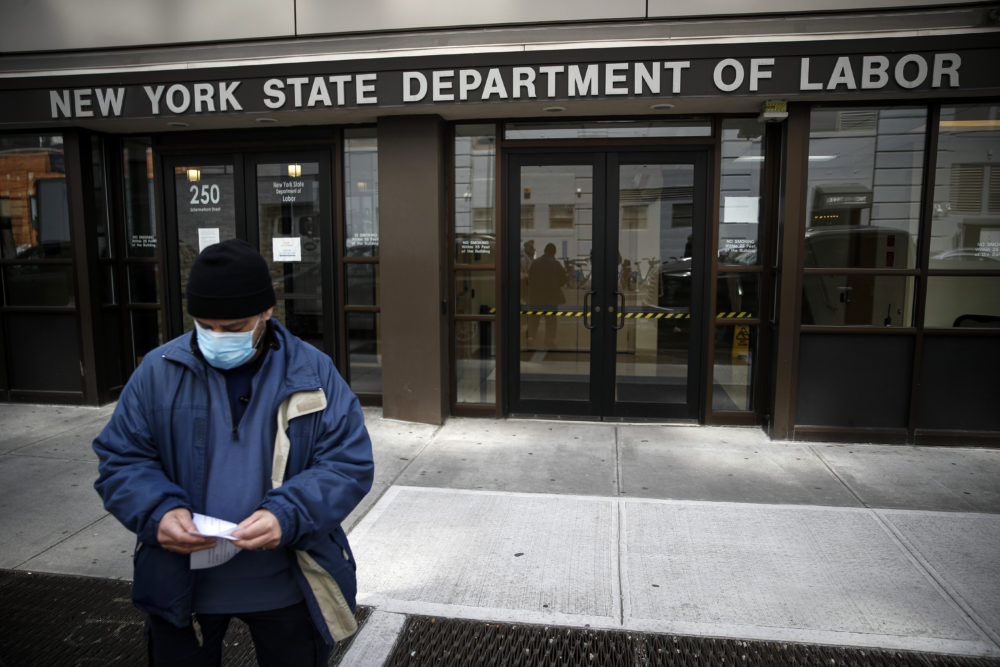

Right now, in the midst of the novel coronavirus pandemic, is no different. More and more American workers are being let go by businesses that are cutting back on their operations or simply shutting down. That’s true in other countries, too—from China (where at least 5 million workers have lost their jobs) to Italy (which last week surpassed China in coronavirus-related deaths, and the government has now closed factories and all production that is not “essential”).

What we face then is an unemployment pandemic.

According to the latest report from the Bureau of Labor Statistics (pdf), in the week ending 14 March, the advance figure for seasonally adjusted initial claims was 281,000, an increase of 70,000 from the previous week’s 211,000 initial claims. This is the highest level for initial claims since 2 September 2017.

But that was a little over a week ago. Now, the number is even higher. We don’t know how much higher in terms of the United States. But we do know, from the New York Times, that in just 15 states initial claims were more than 629 thousand—about three times what they were for the entire nation in the previous week.

It’s no wonder, then, that the Trump administration wants states to hide those numbers from view. Just as it’s approached the novel coronavirus pandemic not as a health problem, but as a public relations issue, so it is treating the unemployment pandemic. Hide it from view and pretend it will go away.

Until, of course, it can’t.

And in both cases, it’s workers who will bear the brunt of a pandemic they played no role in creating.

Endnote

- On two occasions since World War II, the official (U3) rate has exceeded 10 percent, and that doesn’t even count workers who are too discouraged to look for a job or those who are forced to work part-time jobs when they’d really prefer a full-time position (who are included in the U6 rate, which is always much higher than the official rate).

[David Ruccio is a member of the Higgins Labor Studies Program and Faculty Fellow of the Joan B. Kroc Institute for International Peace Studies.]