Shalini Ghosh runs a fairly popular boutique chain selling ethnic garments and gift items from West Bengal. She had five outlets across Kolkata and had lined up plans to expand both inside the State and outside. Then the pandemic broke out and instead of expanding she had to close down three outlets. And now, as the pandemic eases off, she finds herself stuck with a huge inventory of unsold stock. She had been paying all the artisans, weavers, and tailors associated with her chain throughout the challenging period and was running low on funds.

After deciding to clear the unsold stock to make up for the cash burn, Shalini went on social media to hire a few executives to aggressively market products from her two remaining outlets. Almost immediately, she was flooded with resumes, and the most surprising thing was the significant number of resumes she received from people with post-graduate degrees or even higher qualifications.

Anand Sekhar*, who has at least two post-graduate degrees, lost his job in Delhi during the pandemic. He returned home to West Bengal but struggled to find another job. Eventually, he joined a small straw manufacturing unit near Ultadanga in north Kolkata, owned by his maternal uncle.

Police detain Congress Party activists demanding job opportunity to unemployed youths in Hyderabad in October 2021.

Abhijit and Neelima* both have degrees in two subjects each. Abhijit used to work in a new media company, while Neelima was with a Hyderabad-headquartered power sector company. Both lost their jobs almost simultaneously and struggled for months before finally moving to a village outside Shantiniketan, where the husband ferries passengers in a Toto e-rickshaw, while the wife is trying to make a go of converting their mud hut into an eco-homestay.

Nationwide phenomenon

These are but a few of thousands of such stories one hears from across the country. One way to look at it is as people reinventing themselves and picking up skills for other occupations. But the other, more logical and certainly more alarming, hypothesis is that India is heading towards a critical degree of unemployment among the educated. A look at the disaggregated unemployment data shows just how serious the problem is.

According to a Centre For Monitoring Indian Economy (CMIE) report that analysed the data between January and April 2022, the level of unemployment among graduates was 17.8 per cent, compared to about 11 per cent in 2017. Some States such as Rajasthan, Bihar, and Andhra Pradesh have not been able to provide jobs for more than a third of their graduates.

The pandemic seems to have exacerbated the situation: the number of unemployed graduates was 19.3 per cent in 2021 (compared to 14.9 per cent in 2019 and 15.1 per cent in 2020). The disruption to economic activity in this period, as large numbers of workers returned to their hometowns, could explain this increase.

Going by the CMIE statistics, one State that has witnessed a high level of unemployment among graduates is Bihar, with 34.2 per cent of its graduate workforce without a job. Bihar also had the second largest number of returning migrant workers in 2020, which would have made matters worse for those seeking work.

In contrast, states such as Gujarat, Karnataka, and Odisha, among others, had less than 10 per cent unemployment rate among graduates as of April. It was just 6.1 per cent in Karnataka, the only State that has succeeded in keeping unemployment among graduates below 11 per cent since 2016.

States with strong industrial clusters or those with more information technology (IT) and IT enabled services companies are able to provide more jobs to those with higher education. For instance, States such as Maharashtra and Tamil Nadu had lower unemployment rates of 9.4 per cent and 10.6 per cent, respectively, among graduates.

In January, the Union Labour and Employment Ministry released the second quarter figures for 2021 from the Quarterly Employment Survey (QES), part of the All-India Quarterly Establishment-based Employment Survey (AQEES). It showed that total employment in nine select sectors was 3.1 crore for the quarter ending September 2021, 2 lakh higher than the quarter ended June 2021.

The report, which covered manufacturing, construction, trade, transport, education, health, accommodation and restaurants, IT/BPOs, and financial services sectors, was released by Labour Minister Bhupender Yadav, who said on social media that he was “happy to note that the employment is showing an increasing trend”.

However, the Minister’s happiness might be short-lived. In June 2022, CMIE data showed that the unemployment rate had spiked to 7.80 per cent, up from 7.12 per cent in May 2022. From 404 million jobs in May 2022, only 390 million jobs were available in June 2022, putting about 14 million people out of employment.

Rural India was the worst hit, primarily due to the patchy southwest monsoon in the first fortnight of June, which led to reduced demand for and participation of the labour force. Overall unemployment in the quarter ended June of 2021-22 also surged to 12.6 per cent from the previous quarter’s 9.3 per cent.

In the past 12 months, the unemployment rate has breached the June level four times: August 2021 (8.32 per cent), December 2021 (7.91 per cent), April 2022 (7.83 per cent), and February 2022 (8.11 per cent), but it is significant, as CMIE notes, that one of the biggest falls happened in the post-lockdown month of June 2022.

Yet, the job market is thriving, according to the JobSpeak Index of Naukri.com, an online recruitment service. The Index is a report that gauges month-on-month hiring trends based on recruiter activities on its website. The Index stood at 2878 in June 2020, second only to the peak in February this year when it crossed 3000. It shows that since the start of this year, hiring activity has been growing steadily, showing a roughly 22 per cent year-on-year growth in June 2022 versus June 2021.

Where the jobs are

The demand seems to be highest for freshers, with this segment recording the highest yearly growth. The growth in jobs for freshers was led by Travel & Hospitality (+158 per cent), Retail (+109 per cent), Insurance (+101 per cent), Accounting Finance (+95 per cent), BFSI (+88 per cent), and Education (+70 per cent). Entry-level hires were highest in Kochi and Mumbai.

Pawan Goyal, Chief Business Officer, Naukri.com, said: “With the economy growing at a steady pace, the job market is also seeing a consistent uptick in hiring across key sectors and cities.”

R.P. Yadav, Chairman and Managing Director of Genius Consultants, a staffing solutions agency, echoed a similar sentiment. He said: “After a steep decline in the wake of the pandemic, when the economy was recovering, the second wave caught us off-guard and derailed progress. Subsequently, it has looked much better. Businesses are back on track, markets are performing better, and pre-pandemic conditions are getting in place. Manufacturing units and offices are functioning at full capacity, consumer sentiment and buying patterns have improved.”

However, these numbers do not reveal the complete picture. About two-thirds of India’s almost 1.4 billion people are between the ages of 15 and 64. Speaking to Frontline, Jawhar Sircar, a former civil servant who was with several industry and labour-related departments at the Centre and in West Bengal, said: “India’s labour force participation ratio is 47.1 per cent. This means 47 per cent of the population in the age group of 15-60 year is getting work. In Bangladesh, this ratio is 57 per cent, in Nepal it is 80 per cent and in Europe, the average ratio is 65-75 per cent while in the US it is 67 per cent. The global average is 65 per cent. In India, enough jobs are not available.”

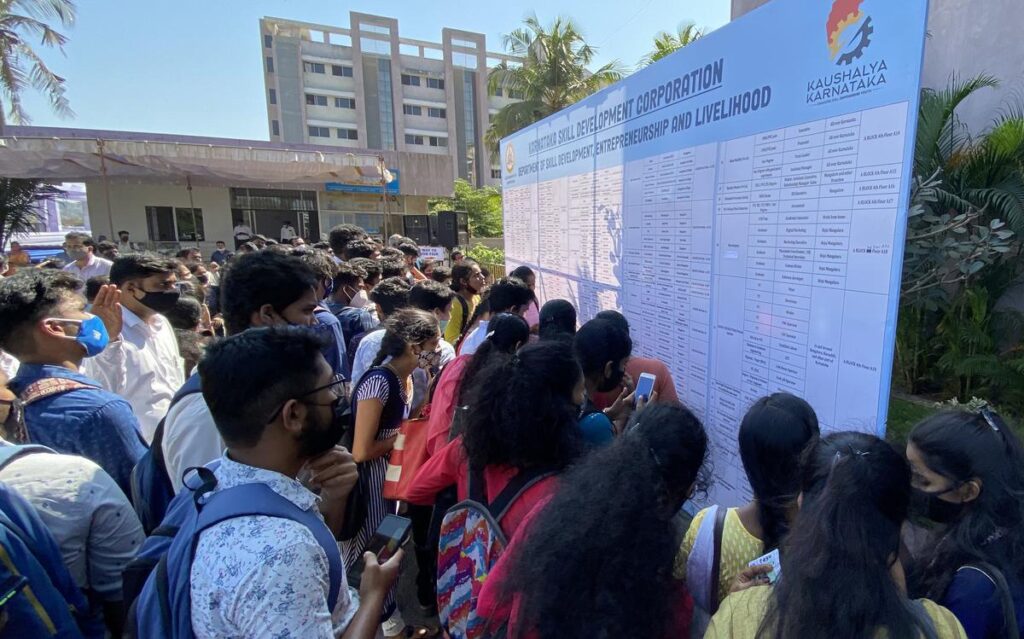

The scale of the despair goes on display whenever government undertakings announce plans to hire. Last year, 18,000 people, a significant number of them reportedly post-graduates and doctorate students, applied for 42 government vacancies for cooks, gardeners, and peons in Himachal Pradesh last year. In January this year, a railway recruitment drive in Bihar and Uttar Pradesh turned violent, as groups protesting mass unemployment blocked roads and railway lines. It was found that more than 12 million people had applied for 35,000 clerical jobs with the Indian Railways, which continues to be India’s largest employer.

Kaushik Basu, Cornell University Professor and former Chief Economist of the World Bank, wrote in a recent article in Ananda Bazar Patrika, in which he said: “In India, unemployment among the youth is 25 per cent, which means one out of every four young job seekers is unemployed. You would hardly find such high and alarming rates of unemployment in countries other than a few Central Asian ones that have gone through some devastation or the other. All the countries with which India prefers to compare itself have this [youth unemployment] rate below 15 per cent.”

What India needs to do

In a recent study, global management consultancy McKinsey & Co said that India needs to create at least 90 million jobs by 2030, when a new generation will reach the working age, millions of workers will move from agricultural work to better-paid jobs in other sectors, and an increasingly larger number of women will participate in the labour force.

To create jobs for so many people, the country has to boost its annual gross domestic product (GDP) growth; a McKinsey report said that the country has to achieve a GDP growth of 8-8.5 per cent on average every year from 2023 to 2030, which sounds a bit ambitious given the economic slowdown and the extreme uncertainties posed by the pandemic.

A number of studies suggest that the number of unemployed in the country today could be 40-45 million. But the true extent of unemployment is not captured even by these numbers, because they do not account for the large number of people in disguised unemployment, that is, working below their potential. This is especially true if one considers India’s level of economic development and lack of social security benefits, which means that relatively few people can afford to stay unemployed.

Interestingly, the official definition of “unemployed” applies to those people who are of working age and are seeking a job, but are unable to get one. But does everyone who enters the working age population seek a job? For instance, existing sociocultural norms and the lack of social safety have resulted in fewer women participating in the labour force than is possible.

As per ILO figures, India’s female labour force participation at 25.1 per cent in 2021 was lower than the global average. The corresponding figure for Bangladesh was around 53 per cent. Besides, when prospects are bleak, even men feel discouraged to look for jobs.

India’s overall labour force participation rate, according to CMIE data, was about 40 per cent, a fall from the already low 46 per cent in 2016. For the 15-24 age group, it was 47.1 per cent. Thus, unemployment statistics do not reflect the true numbers of people who are unable to work to their full potential. The pandemic has only exacerbated this situation.

Many economists have suggested that to create more jobs, India must focus on labour-intensive sectors such as trade, transportation and storage, and hotels and restaurants, and on knowledge-intensive sectors such as communication and broadcasting, financial services, education, health care, IT, business process management, and other professional services. These sectors will collectively have to sustain and improve on historical strong momentum to deliver the number of jobs required.

The agriculture sector, which continues to bear more employment than it can sustain, will have to increasingly focus on increasing productivity, thereby continuing to shed jobs, they added. (The share of agriculture in total employment jumped to 39.4 per cent in 2021 from 38 per cent in 2020, as per CMIE statistics.)

The excess labour can move from agriculture into higher-productivity sectors, including agro-related sectors such as food processing. It is estimated that nearly 30 million farm jobs could move to other sectors by 2030.

Burgeoning workforce

As noted earlier, McKinsey has predicted that the period between 2023 and 2030 will require a GDP growth rate of 8-8.5 per cent annually to generate 90 million net new jobs by 2030. This figure includes 60 million new workers expected to join the workforce based on current demographics, and the 30 million workers expected to move from farm work to non-farm sectors by 2030.

The asking figure of 90 million non-farm jobs by 2030 translates into an annual growth of 1.5 per cent in net employment from 2023 to 2030. This will be in line with the growth in employment that the country achieved between 2000 and 2012 (it reached an all-time high of 50.8 per cent in the fourth quarter of 2012), and almost double the 0.8 per cent historical employment growth over the past 20 years. Between 2012 and 2018, 4 million non-farm jobs were created annually. Starting 2023, this number must be tripled to absorb the influx—that is, 12 million non-farm jobs every year. And if an additional 55 million women enter the labour force, an optimistic projection that could partially correct the historical under-representation, then the job creation imperative will only become greater.

There are broadly two issues at play here: one is the job losses caused by the pandemic and the second is India’s historically high unemployment rate. One must also look at the issue of employability. Debashis Bhattacharya, a human resources expert currently working with Interra, said that the employability crisis among graduates was a conundrum that negates India’s much-vaunted demographic dividend.

India is considered a powerhouse when it comes to available workforce, with 50 per cent of the country’s population below the age of 25, but where is the employability, he asked.

As per the World Economic Forum, of the 13 million people who join India’s workforce each year, only one in four management professionals, one in five engineers, and one in 10 graduates are employable.

This allows us to trace the high rate of youth unemployment in India directly to education. Schools and colleges are failing to train students for both the job market of today and the market of the future.

The students are not prepared adequately even for traditional jobs, leave alone the tech-driven jobs of the future, which, as a 2020 World Economic Forum Report highlighted, will look for skills in programming, data science, big data, machine learning, artificial intelligence, web development, etc.

There are, therefore, three broad categories of the unemployed in India today: unemployed youth and job seekers, youth who are unemployable, and youth, often highly educated, who have lost jobs. These three categories, put together, have caused the employment crisis to assume frightening proportions.

During his election campaign, Prime Minister Narendra Modi vowed to create millions of jobs. He is now under tremendous pressure to show that his government is making progress on that promise. It is this pressure that led to his announcement in June that 10 lakh Central government vacancies would be filled in 18 months and of the much-hyped and politically sensitive armed forces hiring programme called Agnipath, which are crucial to Modi’s hopes of winning a third consecutive term in office.

However, with runaway inflation (annual inflation rate in June 2022 was 7.1 per cent, well above RBI’s target range of 2-6 per cent threatening to derail a fragile post-pandemic economic recovery and rampant unemployment stoking discontent, it remains to be seen how effective such impulsive and hastily conceived projects will be in resolving India’s entrenched unemployment crisis.

[* Names have been changed]

(Ritwik Mukherjee is a post-graduate in economics and has worked for over three decades in business and economic journalism. He is currently an independent journalist and author. Courtesy: Frontline magazine.)