(Independent India’s first elections were held from October 25, 1951 to February 21, 1952. To commemorate that monumental exercise, we are publishing this article from The Wire.)

Any perceptive observer of Indian politics can make two comments about Indian democracy without any fear of contradiction: democracy in India is doing badly; and it is doing rather well. It is doing badly in that democratic institutions have fallen by the wayside and are in grave risk of either atrophy or of being appropriated by undemocratic elements. Our democracy has become very precarious. It needs to protect itself from its practitioners and beneficiaries. But it does not possess the resources with which to do it. At the same time democracy is doing well in the sense that it is being advocated and upheld as a valid norm, by everybody. Nobody in our politics is self-consciously anti-democracy. Politicians of all hues are opposed to the misuse of democracy by their opponents, not to democracy per se. There are many who do not practise what they preach. But that they should still preach it, is in itself of some significance.

It is true that the idea of democracy is larger than elections and that no democracy can be reduced only to elections. It is also true, however, that no democracy makes sense without elections. It is useless to talk of an election-less democracy, even though some of our leaders did talk of a party-less democracy. Elections do occupy a central place in the idea and practice of democracy.

On the 70th anniversary of independent India’s electoral democracy, it may be well to remind ourselves that India’s tryst with electoral politics had begun much before 1952. Anyone working on the history of electoral politics in India would be advised to start his/her enquiry at least from 1937, if not earlier. Even when India was a colony, the British had instituted electoral democracy, under which fully elected governments could be established in the provinces, along with a legislative assembly at the Centre, not very different from the parliament of today. Under this arrangement general elections were held twice, in 1937 and 1946. But these elections were different from the general elections that started in 1952, in three crucial respects.

First, the franchise was restricted to around 14% of the population. The voters were chosen on the basis of education, income, property, tax-paying capacity and other such criteria. The common people were generally excluded from the list of voters. Second, the British retained a tight control over both the provincial assemblies (through the Governors) and on the Central Legislative Assembly. The rights of the elected members were not to override those of the Viceroy. Third, and most significantly, the elected representatives, constituencies and most significant, the voters were segregated on the basis of religion. This led to the creation of separate Muslim candidates, constituencies and voters who were separated from non-Muslim candidates, constituencies and voters. Hindus were disqualified from voting for Muslim candidates and vice versa. This was a strange electoral arrangement which could only spread communalism in the minds of the people. It is indeed an irony that India’s initial democratisation was also accompanied by a steady communalisation of the society and politics. The more democracy, the more communalism – that was the operative political principle till 1947.

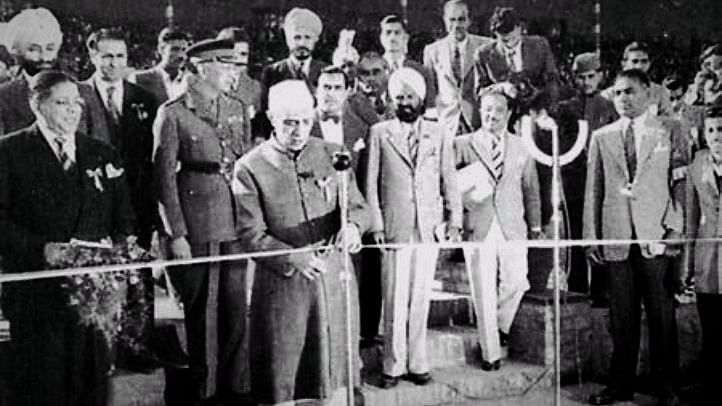

The Indian nationalist leaders did agree to participate in the electoral process but were clearly not happy with it. Jawaharlal Nehru started his campaign for universal adult franchise, joint electorates and a representative Constituent Assembly to frame a new constitution for India, from early 1930s onwards. Eventually the Constituent Assembly was constituted in 1946 and, by the time it prepared the final draft of the Constitution in 1949, India had become independent. The Constituent Assembly also doubled up as independent India’s parliament till the first general elections were held in 1952. Thus it was that separate electorates were given up for good, but not before India was partitioned. And universal adult franchise was adopted by our constitution.

A shift, at one stroke, to universal adult franchise, was a big move and did have many adversaries, most of them European commentators. It was argued that a country with a literacy rate of 14% should not hurry towards adult franchise, and should only gradually open up the society for it. This indeed was the pattern in most European countries. In France, the headquarters of the French Revolution, women got a right to vote only in 1944. In some European countries full adult franchise was established only as late as 1971. As against these reservations, the Indian leaders were unanimous in their opinion that the illiterate Indian people were certainly not uneducated. If they could defeat the mightiest of the imperialist empire through disciplined collective action, they certainly possessed the capacity to choose their own leaders and rulers. However, the Western suspicions on this great Indian experiment did not completely die out. They retained the apprehension of the eventual collapse of both the Indian constitution and the Indian democracy. The imposition of Emergency in 1975 was seen by them, not as an aberration, but the inevitable culmination of the flawed ideas of the Indian constitution. It was declared that the happy dream of Indian democracy was over!

It was in this kind of atmosphere of suspicion and doubt that independent India approached its first general elections. A total of 176 million voters were to elect over 4,000 candidates both at Centre and in the states. There were three main forces in the fray which could be identified as those of the Right (Janasangh, Hindu Mahasabha and the Ram Raj Parishad), Left (Kisan Mazdoor Praja party of Kripalani, CPI and the Socialists) and the Centre (Congress) , on the ideological spectrum. The Congress under the leadership of Nehru was clearly the favourite of the people. The Communists had been discredited for not having participated in the Quit India movement and for having abandoned the constitutional path of social transformation. The Right, not very popular with the people in the first place, had been further discredited for its involvement in the assassination of Mahatma Gandhi. Nehru was not just the leader of Congress but also of the freedom struggle and a major figure in the making of Indian constitution.

The election campaign went along anticipated lines and has not changed very much since the then. The Left accused the Congress of appeasing the capitalists; the Right accused the Congress of appeasing Muslims; and Ambedkar’s party, the Schedule Caste Federation, accused the Congress of neglecting the lower caste groups. Nehru, representing the Congress, turned the entire election into a mandate against communalism and communal violence. He declared in his election speeches: “If any person raises his hand to strike down another on the ground of religion, I shall fight him till the last breath of my life, both as the head of government, and from outside.”

Apart from seeking a vote against communalism, Nehru focused a great deal on the long-term goals, in his election speeches. Instead of simply making immediate promises to them, he sought to educate them and make them partners and stakeholders in India’s destiny. Nehru saw these elections as a great opportunity to train and educate people into thinking about India’s future together. The election results would have lived up to his expectations. Congress won 364 seats out of 489 in the parliament and 2247 out of 3280 seats in state assemblies.

Seven decades and many general elections later, what does the general picture look like in comparison with the first general elections of independent India? The general participation has certainly gone up. But so have the roles of populism, false promises and a great reliance on emotional appeals made on the basis of caste and religion. Nehru’s great efforts in making people partners in a blueprint of India’s social transformation clearly fell by the wayside since the 1960s. It looked as if the elections, instead of making Indian democracy strong and robust, were actually revealing the darkest sides of democracy, promoting violence, opportunism, casteism and communalism. Why was this so? Why have Indian elections become a source of all the negative traits of democracy? Is it simply because of the quality of humans running Indian democracy or is there a larger structural explanation for the regress and the rot?

Nehru had realised fairly early that the historical forces propelling democracy had shaped up very differently in India and in the West. As he explained in an interview to the American journalist Arnold Michaelis, Europe went through an economic revolution which was then followed by a political revolution. The economic revolution created affluence which could sustain and feed into the political revolution. Democracy and empowerment of the people were part of the political revolution, which was backed up by the economic revolution. India by contrast went through a political revolution first. The institutional and infrastructural requirements created by the political revolution could not be easily met in the absence of the economic revolution. In the West, democracy played an important role in creating a consensual society. But a baseline consensus already existed which made democracy functional and effective. The democratic trajectory in the West went along the following route: The economic revolution created affluence which was gradually diffused among the people. This in turn created a baseline consensus. The democratic apparatus in the West was built on this baseline consensus and subsequently expanded it.

The Indian conditions were different in some crucial respects. Absence of affluence was one feature. The presence of great social and religious plurality was another. Plurality could be sustained and nurtured only with the help of a baseline consensus. But the necessary ingredient in the building of consensus – affluence – was missing. This was the structural dilemma confronting Indian society in its tryst with democracy. Its resolution was necessary but also difficult in the absence of some crucial ingredients. The dilemma could be understood through the following syllogism: A) India’s great plurality needed not only to be recognised but also respected and promoted. B) Democracy, in order to do well, needed a baseline consensus as a precondition. Democracy could promote consensus, only if a baseline consensus existed in the first place. A baseline affluence was virtually a precondition for this baseline consensus. C) India’s great plurality rendered this baseline consensus difficult to achieve.

What to do? Nehru understood the dialectical relationship among affluence, consensus and democracy. One could create the other but also needed the other in order to grow. But neither could be created by sheer will-power. The existing economic conditions did not allow for any kind of consensus to be built up. One could also not wait for the maturing and diffusion of affluence to eventually feed into a democratic consensus. Nehru therefore placed a great deal of faith in the elections as the instruments which would create the baseline consensus. The consensus would then nurture democracy. And democracy would promote and uphold plurality.

It was for these reasons that Nehru accorded supreme importance to elections in the nurturing of democracy and plurality. His effort through the first three elections was to generate a consensus around certain key ideas regarding India’s future. For him, elections were the main instrument through which Indian people would collectively acquire faith in a common future. This was a Nehruvian project. It has now run into deep and troubled waters.

Indian elections today are a great carnival of democracy. There is much greater popular participation than before. Yet any observer from the time of independent India’s first general elections would be disappointed by the performance of Indian elections. The great popular participation is devoid of any baseline consensual element and a collective imagination about the future. The elections no longer perform the tasks Nehru wanted them to. They promote democracy without consensus. What would be the social role of elections and their relationship with democracy seven decades from now? Only future can tell.

(Salil Misra teaches history at the Ambedkar University, Delhi. Courtesy: The Wire.)