❈ ❈ ❈

The Profits of Fear

Alberto Toscano

“They ain’t seen shit yet. Wait until 2025.” So said Tom Homan, Donald Trump’s recently named “border czar,” at last July’s National Conservatism conference, where Homan announced that, should Trump return to the White House, he would run “the biggest deportation force this country has ever seen.”

A few months earlier, Stephen Miller, Trump’s incoming deputy chief of staff and chief anti-migrant agitator, laid out his own dark vision for “the most spectacular migration crackdown”: enlisting the full range of federal powers for a mass deportation campaign that would overwhelm immigrant-rights lawyers and any efforts to shield undocumented workers from surveillance, incarceration and expulsion.

Now, less than two weeks before Trump’s inauguration, the threats against municipal or state officials willing to extend “sanctuary” have only grown more explicit, as when Homan recently vowed to prosecute Chicago Mayor Brandon Johnson if he continues to “harbor and conceal” asylum seekers.

Trump’s mass deportation plans are alarming but they are also a conscious (if turbocharged) recap of the United States’ long history of anti-migrant state racism, as well as the product of a very profitable system of detention and surveillance supported by successive administrations of both major parties.

Whether they take the “spectacular” form Miller seeks, they will pay dividends in multiple ways: enabling further profiteering by private prison and other carceral corporations tapped to manage the coming crackdown, while permitting Trump to profit politically from the claim that migrants are the prime culprits of “American carnage.” That this strategy knows no moral or factual limits was evident in the MAGA response to the recent violence in New Orleans and Las Vegas — declaring “We need to secure that border” even as both attacks were perpetrated by native-born U.S. citizens with lengthy military backgrounds.

To challenge the violent scapegoating of migrants that is coming will require mobilizing against the Trump administration’s claim to be the champion of the “American worker.”

150 years of anti-migrant lawfare

The rhetoric surrounding the MAGA movement’s headline policy is like a greatest hits compilation from 150 years of nativist anti-migrant lawfare. Trump’s Sinophobic rants against Chinese fentanyl coming over the border recall how Chinese workers were the first target of repressive and racist U.S. immigration laws, beginning with the Page Act of 1875, as well as of a nativist labor movement that fought to keep labor white.

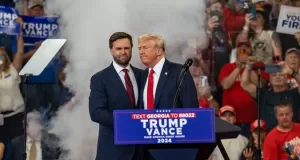

But that’s just the beginning. In 2015, Trump invoked Dwight Eisenhower’s infamous 1954 “Operation Wetback” deportation drive as a possible model for his own administration to follow. The lies Trump and Vice President-elect JD Vance spread this fall about Haitian immigrants in Springfield, Ohio, echo how crucial anti-Black and anti-Latino racism have been, ever since the 1980 Mariel boatlift of Cuban and Haitian immigrants, in framing migration as a national security crisis. Republicans’ 2024 platform promise to “deport pro-Hamas radicals” from college campuses reminds us of how frequently anti-migrant policies have been tied to political panics about foreign subversives, from the 1952 McCarran-Walter Act, which classed communists and anarchists as “deportable aliens,” all the way back to the Alien Enemies Act of 1798, used to justify the mass internment of Japanese Americans during World War II (and now also cited by Trump and his cronies as a means to sidestep legal hurdles to rounding up millions of undocumented immigrants). Now Congress is poised to pass the Laken Riley Act with considerable Democratic support, further expanding mandatory detention, including of documented immigrants, under the pretext of a nonexistent wave of “migrant crime.”

If MAGA’s xenophobic ideology has hardly innovated on its forebears — standing out primarily for its unalloyed crudeness — its efforts to turn nativist racism into a core policy platform also find precedents in the recent history of immigration law and its enforcement.

Bill Clinton’s administration, and especially his support for bills such as the Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act that criminalized migration, were a watershed moment for the United States’ “deportation machine.” As Silky Shah, executive director of Detention Watch Network, has argued, the punitive shift during the Clinton years facilitated the merger of immigration enforcement and the prison industrial complex into a single carceral landscape.

It was in 2014, during the presidency of Barack Obama — nicknamed the “Deporter-in-Chief” long before Trump took office — that the same Tom Homan, then a senior figure in U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), first began promoting the idea of using “family separation” to deter immigration. While Obama balked at implementing the idea, he nonetheless honored Homan with a Presidential Rank Award the next year. And as Shah notes, the Obama’s administration’s work to connect the detention / deportation system with law enforcement “expanded and set up a powerful machinery” that Trump would later exploit.

Private profit, public propaganda

An important dimension of these entwined systems was privatization. Under the cover of benevolent “reforms,” the Obama administration oversaw both the increased federal prosecution of immigration offenses like unlawful re-entry and the increased use of private prisons and corporate “alternatives to detention” for migrants, including various forms of surveillance and “e-carceration.”

For its part, and up to its dying days, the Biden administration extended lucrative contracts with the corporations that run the private facilities that warehouse the majority of detained undocumented migrants—more than 90% of ICE detainees were in private detention centers as of July 2023 — despite documented cases of “medical neglect, preventable deaths, punitive use of solitary confinement, lack of due process, and discriminatory and racist treatment,” as The Guardian reported. Even detention centers the Department of Homeland Security’s Office of Inspector General explicitly demanded be shut down still remain open.

Human rights groups have protested the brutalities that have resulted from the Biden administration’s reliance on the multi-billion-dollar detention industry, led by companies like GEO Group (formerly Wackenhut) and CoreCivic (formerly Corrections Corporation of America). Meanwhile, as The Lever reported, private equity firms have made sizeable investments in federal immigration detention facilities, “meaning opaque, unaccountable, and profit-gouging Wall Street interests are set to make hundreds of millions of dollars detaining and surveilling the country’s immigrants.”

Now the private prison industry, which already saw its stocks boosted by news of Trump’s electoral victory, anticipates a windfall under his second administration. As the executive chairman of the GEO Group declared on a post-election earnings call: “We expect the incoming Trump administration to take a much more aggressive approach regarding border security as well as interior enforcement, and to request additional funding from Congress to achieve these goals.” That increased aggressiveness against migrants translates directly into increased revenues for GEO and its ilk.

The profit to be made from the racialized punishment of undocumented migrants doesn’t stop with detention and deportation, but also very much includes the electronic monitoring and surveillance of migrants. ICE’s Intensive Supervision Appearance Program includes ankle monitors, surveillance “watches” and facial-recognition smartphone apps—all of which, alongside data mining, are the object of lucrative government contracts. Given some skepticism that the Trump administration will be able to carry out all of its draconian plans — Evan Benz, an attorney with the Amica Center for Immigrant Rights, notes there is “no cost-effective or practical way for ICE to lawfully detain and remove all three-plus million migrants on the non-detained docket, despite what Trump and his fascist minions may be dreaming of for next year” — even a failure of the mass deportation campaign would still prove profitable to private prison interests, while spreading misery and terror among migrants.

An economy of fear

To look at the machinery of detention and deportation that Trump and his cabinet of moneyed bigots are revving up is to behold a whole political economy of fear and punishment, generating private profit out of the fuel of demagogic propaganda, paying the psychological wages of nativism while lining the coffers of corporations.

For migrant workers, fear has always been an economic factor: forcing them into lower- wage jobs, hindering unionization, enabling despotic employers. As critical immigration scholar Nicholas De Genova explains, the principal function of deportation in capitalist economies dependent on immigrant and undocumented labor is not actually expelling such workers, but subordinating them, rendering their labor cheap and controllable because of the workers’ deportability.

Homan himself has called for expanding temporary visas for seasonal workers to year-round migrant workers in the dairy industry, which is so reliant on undocumented workers that their absence would double the price of milk. When they’re not monstered as threats to national security, undocumented workers are reduced to factors of production, less important than the animals they tend to, the commodities they produce.

It’s clear that the primary target of Trump’s mass deportation plans is not “migrant crime” but that vast part of the U.S. working class composed of undocumented workers and all of those who fall under the fearsome shadow of deportability — not least student activists mobilizing against genocide. That makes the defense of migrant lives not just a priority of any movement for social justice, but a political and labor struggle as well. For that struggle to gain momentum, it will be necessary to break the reactionary equation of the working class with whiteness and national citizenship that has lingered ever since the late 19th Century.

In 2018, thousands rallied against ICE’s family separation programme — including Democratic politicians like Kamala Harris who later pivoted to a “tough-on-migration” message. In a promising development, Liz Shuler, president of the AFL-CIO, declared this week that fighting back against workplace raids and mass deportations is a “top priority” for the labor movement. Countering Trump’s attack on migrants will require a movement, with migrant workers at its center, that goes beyond humanitarian concern and takes on the forbidding but necessary task of dismantling the deportation machine.

[Alberto Toscano teaches at the School of Communication, Simon Fraser University. He recently published Late Fascism: Race, Capitalism and the Politics of Crisis (Verso) and Terms of Disorder: Keywords for an Interregnum (Seagull). Courtesy: In These Times, an American independent, nonprofit magazine dedicated to advancing democracy and economic justice.]

❈ ❈ ❈

Donald Trump’s War on Migrants

Andrea Mazzarino

This country, once a haven for immigrants, is now on the verge of turning into a first-class nightmare for them. President Donald Trump often speaks of his plan to deport some 11.7 million undocumented immigrants from the United States as “the largest domestic deportation operation in American history.” Depending on how closely he follows the Project 2025 policy blueprint of his allies, his administration may also begin deporting the family members of migrants and asylum seekers in vast numbers.

Among the possible ways such planning may not work out, here’s one thing Donald Trump and the rest of the MAGA crowd don’t recognize: the troops they plan to rely on to carry out the deportations of potentially millions of people are, in their own way, also migrants. After all, on average, they move from place to place every two and a half years — more if you count the rapid post-9/11 deployments and the Global War on Terror that followed, often separating families multiple times during each soldier’s tour of duty.

Soldiers, sailors, and airmen know what it means to be out of place in a new community or in a country not their own. President Trump and his crew are counting on our armed forces being able to live with forcibly taking people from their homes and separating families right here in the United States, an experience that many of them are all too familiar with. As a military spouse myself, I wonder how amenable they will be to the kinds of orders many Americans can already see coming their way.

An Uncertain Future

Donald Trump’s goals have been outlined in countless campaign speeches, rallies, and press conferences, as well as in Project 2025. According to Tara Watson and Jonathon Zars of the Brookings Institution, his administration could, in fact, do a number of different things when it comes to immigrants. One possibility would be to launch a series of high-profile mass deportation events in which the military would collaborate with federal, state, and local law enforcement, instead of leaving such tasks to Customs and Border Patrol (CBP) and Immigration and Customs Enforcement, the agencies typically responsible for managing migration. To do so, the federal government would have to expand its powers over local and state jurisdictions, including by imposing stiff penalties on sanctuary cities, where local officials have been instructed not to inquire about people’s immigration status or implement federal deportation orders.

Watson and Zars assume that the policies of the second Trump administration will impact a number of other vulnerable groups as well. For example, about four to five million people with temporary parole status (TPS) or a notice to appear in immigration court are seeking asylum, having fled political persecution or humanitarian disasters in their home countries. Millions of them would (at least theoretically) have to return to the situations they fled because the new administration may not grant their petitions. It could even try to repeal TPS for the approximately 850,000 individuals who already have it.

It might also reinstitute the “remain in Mexico” policy last in place in 2019, which required Central and South Americans requesting asylum to wait on the Mexican side of our southern border — a measure the Biden administration repealed due to significant safety concerns. Also at risk would be the two-year grace period granted to approximately half a million people from war-torn or politically unstable countries like Haiti, Ukraine, and Venezuela, while new people would probably no longer be admitted under that program and asylum might be denied to those caught up in this country’s backlogged immigration courts.

Additionally, President Trump could try again to end Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals, or DACA, a protected status that now covers more than half a million young people who came to this country as kids. His administration would also undoubtedly slow-walk legal paths to immigration, like the granting of student and work visas to people from China, and could institute policies that would make it ever more difficult for immigrants to access services like Medicaid and public education. His divisive rhetoric around immigrants, calling them “vermin” who are “poisoning the blood of this country,” has already created a climate of fear for many migrants.

A Merging of Powers

In the early 2000s, America’s post-9/11 War on Terror, the remnants of which are still underway in dozens of countries around the world, provided an impetus for the U.S. to consolidate its military, intelligence, and law enforcement entities under a behemoth new Department of Homeland Security, the largest reorganization of government since World War II. As part of that reorganization, Customs and Border Patrol has become ever more involved in non-border-related functions like local law enforcement while benefitting from closer resource- and information-sharing relationships with federal agencies like the Pentagon.

CBP officers now use military hardware and training and work closely with Pentagon intelligence. To take just one high-profile example, consider the heroic intervention in May 2022 by both on- and off-duty federal Border Patrol agents, including several from a special search-and-rescue tactical unit, during the deadly elementary school shooting in Uvalde, Texas. While much has (justifiably) been made of the heroism of those individuals who stormed the building, relatively little has been said about the fact that CBP, state, and local law enforcement agents were all on the scene within minutes and that the presence of hundreds of Border Patrol officers may have actually contributed to the confusion and long period of inaction that day.

Perhaps more to the point, few questioned why Border Patrol agents were better prepared to enter an elementary school than a local police force, or why it seemed like such an obvious thing for them to do in the first place.

Given all that, consider this a distinct irony: the flip side of CBP’s speed in arriving at Uvalde is how regularly it has failed to perform a range of functions it’s supposed to carry out at the border itself in a timely fashion (or at all), especially when such functions are not combative in nature. Take the standoff in early 2024 in Shelby Park, Texas, a 2.5-mile stretch of border along the Rio Grande named for a Confederate general. There, Texas Governor Greg Abbott deployed state National Guard members to prevent CBP from actually processing arriving migrants, complaining that “the only thing that we’re not doing is we’re not shooting people who come across the border.” Abbott’s planned standoff marked the first time a governor had deployed a state national guard against federal orders since 1957, when Governor Orval Faubus deployed the Arkansas National Guard to keep black children from attending an elementary school under federal orders.

The Strange Bedfellows Who Would Implement Trump’s Desires

Military troops who would no doubt have to step in to implement migrant deportation plans as massive as Trump’s would occupy a similarly complicated position, both as outsiders on the local scene and as those charged (nominally at least) with protecting innocent lives. Stranger yet, a small but significant slice of any set of troops asked to take part in such deportations would themselves be immigrants. Five percent, or one in 20 servicemembers in our military, were not born here. And there’s nothing new about that. Since the Civil War, hundreds of thousands of noncitizens have served in America’s wars. During times of hostility, which (officially speaking) include all the years since the War on Terror began in 2001, the federal government expedited the legal path of those immigrant troops to citizenship. It remains unclear how a military that has long been diverse will respond to orders to brutalize people, some of whom may come from their very own communities.

As a military spouse and a private practice psychotherapist who treats U.S. troops, refugees, and migrants from our post-9/11 wars, I can also say that our servicemembers — all of them — are migrants of a very real sort. Culturally, our troops understand both migration and multiculturalism because they have to adapt again and again to new towns or cities where residents don’t see them as real members of their communities, where it’s hard to find doctors and childcare within the military’s anemic infrastructure, and still harder to find these services in communities about which they lack knowledge and connections. In the most challenging of such cases, servicemembers and their families end up in countries where they don’t speak the language or know anyone, and where they may encounter justifiable hostility towards their presence.

The experiences of the myriad groups I see in my practice and know in my broad military community overlap in often profound ways that bring images of immigrants to my mind. Many in such populations understand in their bones what it’s like to be the object of local attention, curiosity, even hostility when they venture out each day. They know what it means to constantly translate from your own language and world into that of a local one (or navigate life without knowledge of the native language at all). They also know what it’s like to have all too few resources to handle a medical emergency or an event like the illness or even the death of a loved one that neither the military nor local resources can help with.

I know one military family whose members struggled for two years in a foreign post because one of their children had a physical disability that neither the military nor the local educational system could accommodate, forcing the military spouse to homeschool. When that spouse came down with a severe case of Covid-19 during the pandemic, they searched long and hard for an appropriate doctor to provide outpatient care so that she didn’t have to leave her young children.

Their experiences mirror those of many I see within migrant communities of color here in the U.S., who come up short when they seek educational and health services for children with special needs, and who suffered more gravely during the Covid-19 pandemic due to overcrowded hospitals as well as social isolation and lack of enough connections to care for young family members when one got ill. It’s no wonder that two groups among us with some of the highest rates of anxiety, depression, and suicidality are military families and immigrants from poor countries.

Violence Touches Us All

Broadly speaking, what those two distinctive groups have in common is that, in this century, they felt the most pressure when it came to dealing with this country’s global imperial desires, either by fighting our remarkably disastrous post-9/11 wars or by finding themselves forced to pick up and start over amid the never-ending destruction of those very wars. To end that cycle of migration-as-combat and combat-as-migration, a better world would not dream of kicking out the migrants in this country. Instead, it would be working to bring back the troops from all the places where they are currently still engaged, rather than preparing for conflicts that will only help to create more migrants.

The United States should stop organizing military “exercises” in places like Saudi Arabia and Somalia; stop training troops in countries like Nigeria, Tanzania, and Uzbekistan; and cease drone and air strikes in Syria and Iraq, among other examples of our military involvement abroad. We should just get out. And we should start funneling some of the hundreds of billions of dollars we’ve channeled annually into weapons production into our education system, healthcare, and green infrastructure here at home, so that there’s room for everyone, immigrants included, to be safe and cared for in the communities where they live.

Otherwise, if President Trump manages to realize even a modest part of the immigrant deportation goals he and his political allies have outlined, the bulk of the work of ejection will be done by those for whom it may be the most morally devastating. Many more of our troops than he could ever imagine will, I suspect, be unnerved by what they have in common with the people they’re charged with deporting from their adoptive homeland.

Yes, this may very well be wishful thinking on my part, but I do believe that, Donald Trump or not, our common humanity is likely to win out in the end. After years of studying America’s post-9/11 wars from a range of viewpoints (and listening to those deeply disturbed by their War on Terror experiences), the largest commonality I find among our troops is not a desire to take up arms or fight terrorists in distant lands, or even the experience of being personally victimized — hunted, shot, tortured, or maimed. Rather, it’s the trauma of hurting another human being. It’s wrought from looking a Taliban soldier in the eye at a checkpoint in Kabul and realizing he’s human just like you, or separating a suspected opposition fighter from his spouse and kids during an arrest. It’s the scream of a child whose parent you shot during a raid to prevent an attack on you.

In no small part, the stress of those experiences also came from having to leave your own children for months at a time, knowing that the youngest might not even remember you when you return, or telling your teenager that she has to abandon everything she knows — boyfriend, school, sports teams — to go to a new military town where no one will even know her name. Many of those involved in America’s post-9/11 wars have witnessed another’s suffering in an up-close-and-personal fashion and the ongoing nightmare they face is the possibility of hurting yet more people in all of our names.

Thanks to Donald Trump, at least some of those troops will undoubtedly face the choice of having to do it all again, this time on our own soil. Unless they pause at the memory of what that may be like, Americans could find themselves in an unrecognizable land. It will be a nightmare if, his second time in the White House, Donald Trump launches a war on terror domestically against migrants, because that would be a war on America itself.

(Andrea Mazzarino co-founded Brown University’s Costs of War Project. She has held various clinical, research, and advocacy positions, including at a Veterans Affairs PTSD Outpatient Clinic, with Human Rights Watch, and at a community mental health agency. She is the co-editor of War and Health: The Medical Consequences of the Wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. Courtesy: TomDispatch.com, a web-based publication, founded and edited by Tom Engelhardt, aimed at providing “a regular antidote to the mainstream media”.)