When Frank Carrico talks about why he and his coworkers at the Heaven Hill Distillery went on strike, he talks about family. “I missed out on my kids’ activities” because of forced weekend shifts, he says. “I missed out on a lot, and I don’t want the young people coming behind me to have that happen to them.”

When we spoke, the distillery workers had just come off a six-week strike demanding to maintain a forty-hour week, Monday-Friday, with overtime pay beyond that.

Workers at Frito-Lay struck this summer to end “suicide shifts”: back-to-back twelve-hour shifts with just eight hours’ break in between. More time between extra long shifts was also among the demands that led film and TV crew members to authorize a strike. Textile workers in Italy struck to end eighty-four-hour work weeks (and won big).

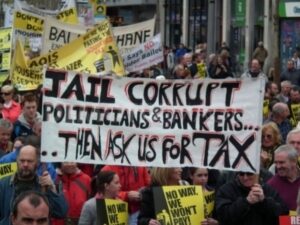

A popular meme on social media reminds us, “Got a weekend? Thank the unions!” But many workers, union or not, have no weekend — and certainly don’t have what the Haymarket strikers in 1886 demanded: “Eight hours for work, eight hours for rest, eight hours for what we will.”

Strikes and the pandemic are exposing how many of us, from Nabisco factories to movie sets, are working twelve-hour shifts, sometimes for days in a row.

Those extra hours take a toll. Study after study has shown that longer work hours lead to shorter lives and higher risk of heart disease.

Longer hours also lead to narrower lives — with less time for family, play, and what you will.

Over decades of fighting, unions won the eight-hour day. And over decades of negotiating, they’ve often given it back by agreeing to overtime schemes linking increased pay to increased work.

That (combined with stagnant or falling real wage rates) leaves workers always hustling to catch up. Overtime may be “voluntary,” but it becomes necessary to make ends meet — or too tempting to pass up.

One former teacher union president told me he had to demand that union staff not offer time for money in negotiations. “Union reps just wanted to get the percentage increase,” he said. “But we wanted control of our work day.”

When it’s a tradeoff between time and money, the boss knows that more time — even if it’s paid double — means more profit. Overtime is still cheaper than paying benefits for new hires.

Film and TV crews won an agreement where management now has to pay extra fines for long hours or short turnarounds. But while a fine may be meant as a deterrent, management’s calculation says, “I make enough money off of your time to pay that fine.” Letter carriers and UPS drivers know how this routine goes — stewards grieve, management pays, repeat next week.

Once you’ve traded time for money, the boss will come after the money too.

Nabisco management was looking to take back weekend premiums and overtime pay after eight hours. They wanted an Alternative Work Schedule, where everyone works twelve-hour days, including weekends, at the regular pay.

The final agreement creates a two-tier schedule. Current workers maintain their Monday-Friday week, but the Awful Work Schedule applies to new hires.

Plenty of workers may want the overtime pay and what it allows them to buy. But we’ve accepted a false choice: you get time or money, but not both.

Our lives end up circumscribed by the demands of work. Our imagination for “what you will” dwindles down to sleep and a quick bite to eat.

Instead of fighting within the frame the bosses give us, we should fight for the life we can create beyond that frame. A life that allows us to know ourselves as more than workers — as family members, friends, political allies, athletes, artists, musicians, or even layabouts.

The boss knows it: your time is the most precious commodity there is.

(Barbara Madeloni is the education coordinator at Labor Notes and a former president of the Massachusetts Teachers Association. Courtesy: Jacobin, an American socialist magazine.)