“There’s this Ayodhya protest tomorrow,” my shift head said as we prepared to leave the office after putting the edition to bed. That was sage advice, since I was to produce the edition the next day, a Sunday. “There may not be any heavy trouble.” I nodded.

As I staggered out of the office past 2 am on December 6, 1992, the only worry on my mind was the possibility of a colleague or two calling in sick, putting extra burden on me and my already-stretched news desk. Bunking office on Sundays was, and remains, a common malady in newspaper offices with staggered weekly days off.

Ayodhya was not a concern to me that cold night.

People would gather in huge numbers, shout slogans, listen to their leaders’ speeches and disperse after a few hours, I had remarked to my colleague. Prohibitory orders were in force, and security at the Ram Janmabhoomi-Babri Masjid complex was so tight that not a bird could flutter in. Certainly, the protesters would remember that the police had fired on out-of-control kar sevaks two years before.

Most importantly, I pointed out to my colleague, the protesters’ leaders — notably the Uttar Pradesh chief minister and a holy man — had promised the Supreme Court, no less, that no harm would come to the structure, that the kar seva planned for the day would involve the chanting of kirtans and bhajans. No politician in his or her senses, I said, would be so irresponsible as to damage a 16th-century mosque that was believed to have been constructed after razing a temple. Come on, I reassured myself, nobody would do anything that could set off a communal conflagration. Politicians are bad, but not that bad.

It was naïveté. Pure naïveté.

❈ ❈

By 1992, teleprinters in most newspaper offices had fallen silent. News had started to come in an electronic form. It was a relief from reams of paper — most stories with multiple “leads” and “takes” — landing on the desk head’s table. The clutter of stories filed by news agencies still existed (it will probably never go away). The enormous volumes of copy had moved inside computer systems.

At 3 pm on December 6, I was the only deskperson in the office. Since forenoon, the wires had filed dozens of reports about tens of thousands of kar sevaks having gathered at the site. The despatches spoke about leading lights of the Ram temple movement making speeches from a terrace. Plodding though the copy, I started merging “takes” (parts) of stories I thought should be shortlisted for page 1. Simultaneously, I was pressing a combination of keys, every five minutes, to bring up the latest agency reports.

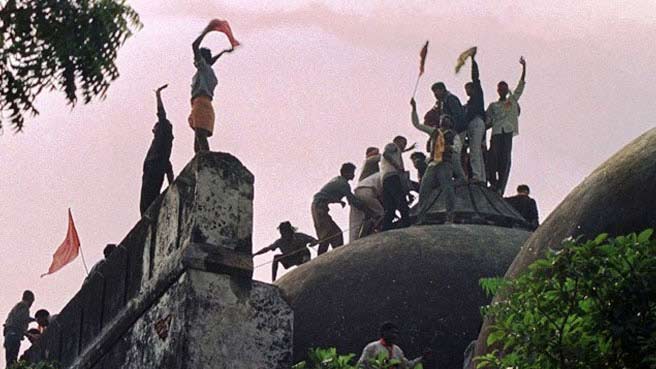

Around 3:30 pm, I noticed an agency flash — a telegram-like message — saying a dome of the disputed structure had come down, not mentioning how. Forty-five minutes later came another flash, announcing that a second dome had been brought down. News of the third dome being demolished came well past 5 pm.

What had been happening all this time now became clear; it was the kar sevaks on the job, egged on by their leaders (some of them predictably denied this; one of them later called it the “saddest day of my life”).

State-owned Doordarshan had no live telecast those days. And there was virtually no private television in India those days, so viewers could watch only what the regime of the day wanted them to watch (it’s the same today, albeit in a different way). For people, newspapers were the only means to get fairly independent information. The press was not polarised those days.

Had private TV channels existed and presented news as they do today, some might have announced the destruction of the Babri Masjid triumphantly. (Who knows, some might have announced it was impending.) But on this day 30 years ago, news about the demolition of the third dome came though the familiar mode: A wire flash. Whether the agency was PTI or UNI, I can’t remember. Not that it matters.

The deed was done. They had accomplished their mission. That it had happened despite all the promises to the Supreme Court, despite the government’s resolve that no harm would come to the structure, did not sink in easily.

The next day, a leading English daily published a page 1 editorial — a rarity — headlined ‘The Republic Besmirched’.

❈ ❈

The demolition of the Babri Masjid touched off protests and violence in India. An estimated 2,000 people were killed in violence in its wake. The after-effects were severe in Pakistan and Bangladesh. Hindus were attacked and their homes and temples targeted. The saddest picture of the aftermath, front-paged by the paper I worked for, showed a resplendent Hindu temple in Bangladesh razed to the ground.

❈ ❈

What shocked me was the ferocity with which the kar sevaks attacked a documentary filmmaker who decided to check out things for herself and moved close to the structure. They groped her, tore her shirt and hurled her into a trench, with murder and more on their minds. The bestiality Ruchira Gupta faced was shocking.

❈ ❈

The violence within India abated after some days, but resurfaced in a most horrible manner in Bombay in March 1993. Terrorists struck in vengeance through serial bombings in a bid to cripple India’s financial capital. Bombay replied to this onslaught in a manner only it can: It was back to normal the next day. My paper greeted the indomitable spirit of the city with a banner headline that read ‘Salam, Bombay’ (Salute, Bombay).

Meanwhile, the gloating and boasting over December 6 continued for months. In May 1993, I heard second-hand accounts of how people from good families who had visited Ayodhya six months before and distributed sweets on the burning alive and the dismembering of people. There was undisguised triumph among a few people that “those people” had been shown their place, but most celebrated quietly.

❈ ❈

Every year, the second half of December sees corporates and star hotels sending cake, dry fruits and mithai to newspaper offices ahead of Christmas and New Year. The December of 1992 was no different. One evening, as we journalists dug into goodies that had been delivered to our office an hour ago, a colleague remarked: “These are Babri demolition sweets.” As he smirked, this shuddh vegetarian’s palm moved back and forth at 45 degrees, mimicking his imagination of how a butcher slaughters an animal.

❈ ❈

For years to come, the air was thick with political chicanery, accusations and counter-accusations. Nothing made sense to me until I heard poet Kaifi Azmi’s lyrics for a song from the 1985 movie Shart:

Zindagi hai zindagi

Zindagi se khelo na

Aadmi hai Ishwar

Aadmi se khelo na

(Life is life

Don’t play with life

Man is God

Don’t play with man)

Post-December 6, 1992, I sometimes wished I could play the song to the people whose incitement and provocation led to a most shameful episode.

(Shirish Koyal is a journalism professor who moved to the teaching profession after working in news rooms for more than 32 years. Courtesy: The Wire.)