(Note: This article appeared in The Reader’s Digest- March 1950. It was condensed from an article by Blake Clark in Christian Herald. It was typed out by Mr. Bhagwan Das. I found these six pages in the documents of Bhagwan Das. From it, we can imagine how much Mr. Bhagwan Das laboured to preserve literature about Dr. Ambedkar. It was the same devotion which made Mr. Bhagwan Das to collect speeches of Dr. Ambedkar in the shape of four volumes as “Thus Spoke Ambedkar Vol. I-4.” It was done by him in the sixties when no other book except “Life and Mission of Dr. Ambedkar by Dhananjay Keer” was available in the market. We are highly indebted to Mr. Bhagwan Das for this historical work.

– S.R. Darapuri)

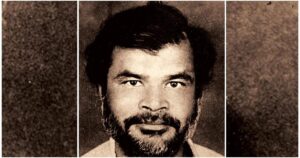

After swallowing insults for centuries, India’s 45 million lowly Untouchables – one-eighth of the country’s population are breaking their shackles of economic slavery and social degradation. At their head is handsome, jet-eyed, 56-year-old Bhimrao Ramji Ambedkar, present Law Minister of India. Himself an Untouchable, and he had dedicated his life to a fight for his people’s rights.

Four thousand years ago Aryan invaders divided India into four Hindu castes. At the top of the ladder, they placed the Brahmans, who were the priests and scholars; on the second rung were the Kshatriyas, the rulers and warriors; on the third were the Vaisyas, the artisans, and merchants; the lowest rung was occupied by the Sudras, unskilled labourers whose destiny was to serve the other three castes. Below them, not even given a place on the ladder, were the outcastes, the Untouchables. Their doom was to do India’s most offensive work, such as sweeping dung from the streets and cleaning latrines. Some lucky Untouchables became curers of rawhide, grass cutters, basketmakers, and wool combers. They cringed as they salaamed; they stepped into the mud to allow others to pass.

A man’s caste determined how he lived from the cradle to the grave even whom he married, whose house he could enter; no one could rise to a higher level than the caste into which he was born. And the caste Hindu could not risk his chances for promotion in the next life by contact with an Untouchable. Sometimes even an outcaste’s shadow was supposed to defile the soul of a Brahman.

Ambedkar’s father was fortunate enough to serve in the British army. He then settled in Satara in the Bombay Presidency because the local teacher agreed to get the boy Bhimrao to attend classes. Bhimrao was the only Untouchable among the 500 grade-school students. He spent the years isolated in a far corner of his classroom, although he was the brightest boy in the class. The teacher would not touch his “polluted” exercise book or let him recite it. As water is considered one of the most easily tainted commodities, when Bhimrao was thirsty the teacher called a servant who turned on the tap for the stream to fall into the lad’s upturned mouth. At recess, while the other boys played cricket, Bhimrao could only stand at a distance and watch.

Despite almost overwhelming handicaps, Bhimrao won a competitive scholarship and entered Elphinstone High School in Bombay. It was a public school, under British rule, and he had to be accepted. But the prejudice continued. In the classroom was a movable blackboard. The boys left their lunches on its platform. During a geometry lesson one day the teacher told Bhimrao to go to the board. A roar of protest went up from the class: “He will spoil our lunches!” Every student ran to the platform and retrieved his food. Then the tainted boy could demonstrate his theorem, defiling nothing but the chalk.

As Bhimrao grew older he learned more about caste. Untouchables were forced to work for some Hindus; they could not bargain over wages but had to accept what the master offered. Every Indian city and village had its Untouchable ghetto, where large families frequently lived in one room, slept on the floor, and shared a single toilet and water tap with as many as 150 people. Bhimrao’s resentment grew. “Education” he said to his father one day, “could rescue our people from the depths.”.

Far away from the slums, in his vast turreted palace, the mighty Gaekvad of Baroda somehow heard of Bhimrao Ambedkar. He had assisted other promising individuals from the Depressed Classes, and now he made it possible for this zealous student to finish college in Bombay, then to sail for further study in the United States.

On his first day at Columbia University young Ambedkar was deeply stirred by two new experiences. He dined in a cafeteria on a basis of complete equality with other students; and he was given a room in a dormitory where he shared the shower room, lounge and drinking fountain with everyone else.

Few students on any campus have ever exhibited such a voracious appetite for knowledge. He became absorbed in history, anthropology, sociology, psychology, and economics. When he received the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in 1917, he had more than double the credits required,

After further study in London and in Germany, Ambedkar returned to Baroda, where he learned from the Gaekvad that he was to be groomed for the Job of Finance Minister. The Accountant General assigned him a desk. Soon a clerk carrying papers for him came down the aisle. In front of Ambedkar’s desk was a carpet, an excellent conductor of contamination. Standing at its far edge, the messenger flung his bundle at the desk. That was the last work Ambedkar received. After six days of mortifying idleness, he asked his superior’s permission to spend his days in the public library.

Then one morning as Ambedkar was leaving his room at an inn he saw a dozen Parsis members of a select caste armed with clubs coming up the stairway. “Get out! Get out!” they shouted. He fled for his life. Unable to find lodgings, he wrote to the Gaekvad, who referred him to the Prime Minister. But the Prime Minister, the highest official in the state told him “Sorry, I can do nothing.”

Except for odd jobs answering correspondence, one of India’s best-educated men lived in Bombay for the next year and a half unemployed, poverty-stricken, and miserable. Finally, he became a professor of political economy at Sydenham College, where he worked only long enough to save money for further study in England. In 1923 he returned to Bombay a barrister with a doctorate of science from the London School of Economics. His treatise, “The Problem of the Rupee,” was acclaimed by economists the world over.

But, to appear before the High Court, a barrister had to have his brief drafted by a solicitor of the same caste. As Ambedkar was the first Untouchable to enter the profession, no one would do this work for him. He took up practice in the District Court, where this rule did not apply. In cases of appeal to the High Court, clients tried to persuade solicitors to assist him, but to no avail. Finally, a Brahman friend who needed the money agreed to help him. Immediately the other barrister boycotted the Brahman and vigorously opposed Ambedkar.

Stubbornly he fought back. Once he said, shaking his fist at a group trying to disbar him, “Someday I will sit on this bench and you will call me ‘My Lord. ‘ He might have fulfilled this prophecy in 1942 when he was offered a judgeship, but he declined the appointment to accept a post on the Viceroy’s Executive Council.

Ambedkar started a weekly vernacular newspaper, now called Janta (The People). Each Saturday afternoon, in every Bombay Untouchable tenement, illiterates eagerly gathered around a fortunate one who could read and listen to Ambedkar’s editorials. Assailing caste for its economic inefficiency, he urged Untouchable boys to take jobs different from those of their fathers.

To help working-class boys and girls go to college, Ambedkar formed the People’s Education Society, which canvassed for funds and leased a deserted army barracks in downtown Bombay. There, at Siddharth College, 2600 of all castes now, receive a full-fledged university education from a faculty of nearly 150 well-qualified professors. Having observed at Columbia American students’ healthy regard for working one’s way through college, Ambedkar introduced the same idea to India. Classes begin at 7:30 and, except for laboratory courses, are over by 10:30, leaving time for students to put in a day’s work in the office or mill.

Appointed as a Labor Member in the Governor General’s Executive Council in 1942, Ambedkar persuaded the government to earmark 300,000 rupees a year for scholarships to send Untouchables abroad for study. The first 30 students, educated in England and the United States, are now back in India at work as engineers, teachers, and lawyers. Even more far-reaching in its effect was his success in getting 12 per cent of the posts in government service reserved for qualified Untouchables.

Some ideas of the Untouchables’ loyalty to Ambedkar may be judged by their response to his first political campaign when he was a candidate for the Bombay Legislative Assembly in 1947. Long before daybreak on election morning thousands of Untouchables, their loose cotton dhotis flapping about their legs, were striding through the dark from district villages into Bombay. By 6 a.m. they were at the voting booths, waiting for them to open.

In this district Hindus far outnumber Untouchables. But while 30 percent of the qualified Hindu voters came to the polls, 80 percent of the Untouchables appeared, and Ambedkar received more votes than any other elected assemblyman but one. “Nothing can stop him,” observed a foreigner, long resident in India. “He has the power of incorruptibility”.

Looking like a serious bespectacled Roman Senator in his immaculate white Indian robes, Ambedkar still lives a simple life. His wife is a physician of the Brahman caste.

Ambedkar is now engaged in perhaps creating a constitution for the biggest task in India – a new republic. As chairman of the constitution drafting committee, he must defend each article before the Constituent Assembly, which must ratify it. A dramatic moment in Ambedkar’s career came on November 29, 1948, when he introduced Article 11, the fulfilment of a lifetime dream. Slowly, in commanding tones, he pronounced it: “Untouchability is abolished and its practice in any form is forbidden … and shall be punishable in accordance with law.” In a unanimous standing vote, the entire Assembly roared its applause.

Ambedkar would be the last to claim that he abolished the slavery of Untouchability singlehanded. Gandhi was a most potent force; largely through his work, the 7 temples are now open to Untouchables. Industrialization, too, with its enforced mingling, has blurred caste lines in the cotton and jute mills. Now, in many cities, the Untouchables eat in the same restaurant with caste Hindus, enter the same barbershop, ride the same bus, send their children to the same school. Last year several thousand Untouchables married outside their group. Even in the villages, some small progress is under way; but the fight for equality in rural areas has been hard.

The very fact that the Untouchables themselves, after centuries of a steadily ingrained inferiority complex, are now taking the initiative in their own cause is encouraging. And their leader is not afraid of adversity. After all, “he says, “kites rise against, not with, the wind!”

(Courtesy: Countercurrents.org.)