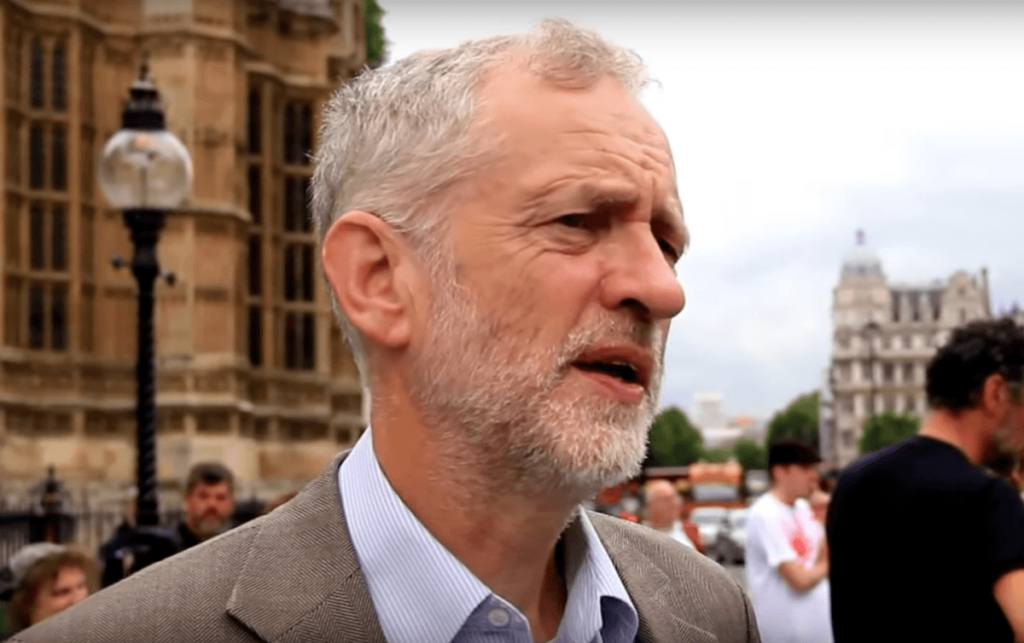

Corbyn’s election as leader of Labour party in 2015 was seen by much of the British left as their best chance to reverse the neoliberal imperialist trajectory of the British state for at least a generation. With a solid track record of opposition to war, nuclear weapons and privatisation, he was able to capture the imagination of a disenfranchised youth sick of corporate-sponsored politicians, quickly turning the Labour party into the biggest mass membership party in Europe, with over half a million members. Two years later, defying all predictions, Corbyn’s Labour managed to overturn the ruling Conservatives’ parliamentary majority in a snap election which was supposed to deliver them a landslide. The prospect of a Corbyn government, with a genuine commitment to reversing the inequality and militarism that had become the hallmark of the western world, seemed to be a real prospect – perhaps even an inevitability.

Yet the general election of 2019 saw the entire project come crashing down in flames. Boris Johnson’s revitalised Tory party, united around a Brexit deal which had escaped his predecessor, stormed back to power with the party’s biggest majority since 1983, stripping Labour of dozens of working class constituencies it had held for generations. Corbyn was replaced by Sir Kier Starmer QC, heralding a purge of Corbynites from the frontbenches. Within a few months, Corbyn himself had been expelled from the parliamentary party.

Explanations for the 2019 result came thick and fast, and their apparent variety obscured the basic argument which tended to run throughout all of them: “Corbyn lost because he didn’t do what I said”. For the party’s right wing, he lost because he was too left; for the left, he lost because he had not moved decisively against the right. For Brexiteers, he lost because of his support for a second Brexit referendum; for Remainers, because this support came too late. For many Corbynites, the result was simply down to contingent tactical mistakes and the hostility of the media; and for Tories, of course, it simply demonstrated, once again, the British people’s instinctive, and correct, abhorrence for socialism.

For socialists, the temptation is to forget the whole sorry saga and ‘move on’. But a serious postmortem is essential if we are to have any hope of learning from the mistakes (as well as the successes) of the movement.

At the outset of this process, it is essential to recognise some basic political realities.

Firstly, the UK is an imperial entity. The relinquishing of formal political rule over most of its colonies between the 1940s and 1970s (with the crucial exception of a string of strategically-positioned island territories such as Diego Garcia, the Caymans, the Falklands, the Virgin islands and around a dozen others) has not changed this simple reality. The basic contours of the world economy created by colonialism – a system of wealth transference from Asia, Africa and Latin America to North America and Western Europe – remain intact, and have indeed been strengthened and perfected in the era of neo-colonialism, to the extent that net resource transfers from the global South to the North today amount to roughly $3trillion per year – triple the value of goods and services flowing the other way, and twenty-four times the total value of North-South foreign aid. Much of this uncompensated wealth transfer is via ‘capital flight’, often illicit, and mostly facilitated through the network of tax havens located in Britain’s remaining island colonies.

Secondly, and contrary to the claims of the colonial left, this wealth does not only benefit a tiny minority. From the 1840s onwards, writes historian Eric Hobsbawm, a ‘labour aristocracy’ began to emerge in Britain – a privileged section of the working class paid above the value of their labour power out of the profits generated by empire. Since 1945, this labour aristocracy, argues Zak Cope, has come to encompass the entire citizenry of countries such as Britain. The domestic accomplishments of Clement Attlee’s Labour government – the NHS, social housing, the welfare state – were largely paid for by the intensified exploitation of the colonies, and colonialism has underwritten social democracy ever since. Even in the era of neoliberalism, which has seen welfare states decimated, the British population (at least up until the 2008 crash) has seen the value of its real wages increase, as intensified exploitation of the global proletariat has led to cheapening consumer goods.

Thirdly, Britain has consistently used its military might to protect and defend this colonial wealth transfer whenever it has been under threat. From the opium wars of the mid-nineteenth century, to the destruction of Libya in 2011, any and every country which has refused to collaborate with the precepts of the colonial global economy has met the wrath of the UK military, either overtly or covertly (with the exception of some Latin American countries, the war against whom has been largely been subcontracted to the US). It is largely for this reason that Britain has invaded no less than 90% of the current member states of the UN at some point.

Social democracy in Britain has always reflected this colonial reality; it has always been a fight over the spoils of colonialism, rather than a challenge to it. The need to uphold and defend the colonial wealth transfer at the heart of world capitalism has always been the singular point of agreement between governments of left and right in the UK. It was, after all, the Attlee government that initiated both Britain’s nuclear weapons programme and NATO, as well as sending troops to Greece, Malaya and Korea to drown their revolutions in blood and restore the rule of more pliant local aristocrats; and it was Tony Blair’s New Labour who spearheaded illegal Anglo-American aggression against Serbia and Iraq as well as sending troops to Sierra Leone and invading Afghanistan, for the fourth time in Britain’s modern history. All of these interventions, from Attlee to Blair, can best be understood as wars to contain threats to colonial ‘global capitalism’ in general (as Christopher Doran has comprehensively shown in the case of Iraq) and British corporate interests in particular (as documented by Mark Curtis). Social democracy in Britain has, in reality, always been social imperialism – the provision of social gains for the British on the backs of millions of superexpoited workers in the global South, backed up by military force where necessary – and the Labour party has, for over one hundred years, been at its vanguard.

This is the historical movement which, in 2015, Jeremy Corbyn suddenly found himself heading. At first, he seemed to be offering something very different. A tireless supporter of indigenous struggles against settler colonial dispossession and discrimination the world over, from Ireland to Palestine, Chagos to South Africa, he had also, for his entire political career, been a CND activist and advocate of unilateral nuclear disarmament. His consistent opposition to war – not only the Iraq war, which 139 Labour MPs had voted against, in the biggest backbench rebellion for 150 years, but even the war on Libya, opposed by only 13 MPs out of 650 – had not only made him a pariah in the Blair years, but set him apart from the entire trajectory of Labour party history. It was this, as much as his opposition to neoliberal austerity and privatisation, that made him such a breath of fresh air to millions disgusted by the ongoing brutality of British policy. And it was precisely this that made him so completely unacceptable to the British ruling class, including the Labour party elite.

It soon became clear, however, that Corbyn was, however grudgingly, coming round to the social imperialist bargain. Perceiving his anti-militarism as an achilles’ heel in a nation with a deep-rooted colonial mentality, the Conservatives tabled parliamentary votes on the bombing of Syria and the renewal of Trident immediately after his election; the aim was to force his hand and, they hoped, damage his standing with the electorate in the process. Would he stay true to his lifelong principles and whip his party into opposing the measures, setting the stage for his portrayal as a limp-wristed, unpatriotic, coward? Or would he support them, pigeonholing himself instead as a feeble-minded, opportunistic, turncoat?

In the end, he attempted to have his cake and eat it – by offering Labour MPs a free vote on both issues, he allowed the Blairite majority to continue to direct the party’s foreign policy, whilst maintaining his anti-war credentials – and salving his own conscience – by making a symbolic one-man protest against it, just as he always had done as a backbencher. This was the Stop The War Coalition’s ‘Not In My Name’ policy all over again, the point being to demonstrate your personal unease with the nation’s warmongering, rather than actively trying to prevent it – not so much ‘Any Means Necessary’ as ‘Nowt to Do With Me, Mate’. When a vote on bombing Syria had come before parliament two years earlier, Corbyn’s predecessor Ed Miliband had whipped Labour MPs to vote against it, resulting in the motion being defeated and military action being called off. Yet the chair of the Stop the War Coalition could not bring himself to do the same, and so, on his watch, the motion was passed. The Typhoons began flying out the next day.

The basic contours of the de facto agreement with his, unremittingly hostile, parliamentary colleagues were now becoming clear: they would be allowed to continue to control Labour’s foreign policy, so long as they joined forces with Corbyn when it came to opposing austerity; an uneasy compromise which would, in other words, combine domestic radicalism with a militaristic foreign policy – the very definition of social imperialism. It wasn’t necessarily intended to be a permanent platform, but the precedent had been set. The next major showdown was Yemen.

Saudi Arabia had begun bombing Yemen in March 2015 in an unsuccessful attempt to restore their hated stooge President Hadi to power following his ouster in a popular rebellion that had quickly gained control of 80% of the country. The official UK position, in the words of foreign secretary Philip Hammond was to “support the Saudis in every practical way short of engaging in combat,” support that quickly came to involve training, targeting, diplomatic support and the pouring of billions of pounds worth of weapons into the conflict. By the autumn of the following year, an estimated 10,000 people had been killed in the war. On 26th October 2016, Corbyn and his shadow foreign secretary Emily Thornberry put forward a motion in the House of Commons calling on the British government to end its support for the Saudi war until an independent investigation into civilian casualties had been conducted.

Yemen perhaps seemed, to Corbyn, more cut and dried. Nuclear weapons, after all, have always been portrayed as a peaceful deterrent rather than a battleground weapon; whilst the bombing of Syria was ostensibly about halting the rise of ISIS, an avowedly genocidal death cult. Making the case against either was always going to be an uphill struggle. But in Yemen, children were being starved to death at the rate of one every ten minutes as part of a war against an entire population, a war which was being conducted in the name of restoring a President too unpopular to set foot in his own country, who had never won a competitive election, and whose supposed mandate, such as it was, had expired years ago. A report the previous month had shown that a third of airstrikes were against civilian targets, and 140 people had been killed in one single attack during the deliberate targeting of a funeral just a fortnight earlier. And all this was being carried out by a monarchical dictatorship who had spent $87 billion on promoting the viciously sectarian ideology behind Al Qaeda and ISIS. Opposing British support for this war – without which, it could not take place – was surely an argument Corbyn could win?

Apparently not. Whether because they were genuinely committed to genocide taking place, or simply willing to exploit it as a means of humiliating Corbyn, around 100 Labour MPs refused to support the motion, even after Thornberry had suggested, under pressure from trade unions representing workers in the weapons industry, that it did not require the suspension of arms exports to the Saudis. It would be the biggest backbench rebellion against their leader during his entire five years in office. To support a genocide. That’s the reality of the British Labour party.

Even Corbyn’s well-wishers told him he needed to ‘shut up’ about foreign policy. Corbyn’s opposition to austerity, plans to crack down on tax avoidance, and raising taxes on the rich, wrote Michael Chessum in the New Statesman, were very popular. But criticising foreign policy could blow it all. The media understood this, he argued, focussing “all of their attacks on [Corbyn’s] links to Irish republicanism, controversies around the national anthem, rumours that Corbyn wants to “abolish the army”.

Paul Mason, meanwhile, one of the most high-profile Corbyn supporters, wrote that “Labour’s number one objective has to be to form a government radical in social and economic policy. For that, I think it should be prepared – as I saw [Greek prime minister] Alexis Tsipras do in January 2015 – to put radicalism in foreign policy on the back burner”- that is, to continue with the imperialist status quo, a much more terrifying proposition when it comes to the UK, with its track record of ongoing colonial extortion and butchery, than Greece, which has not been an imperial power for over 2000 years. By 2019, he had gone further, arguing that Labour “needs to sideline all voices who believe having a strong national security policy is somehow ‘imperialist’. It needs to forget scrapping Trident.” In Mason’s case, this was not solely pragmatic; he was a true believer in the NATO-imposed colonial world order, bemoaning the West’s (supposed) declining military influence and openly arguing that Labour should aim to procure the West an even greater cut of global wealth at the expense of the global South, advocating a “strategy designed to allow the populations of the developed world to capture more of the growth projected over the next 5-15 years, if necessary at the cost of China, India and Brazil … It is a programme to deliver growth and prosperity in Wigan, Newport and Kirkcaldy – if necessary at the price of not delivering them to Shenzhen, Bombay and Dubai,” and to do this “by reversing the 30-year policy of enriching the bottom 60%” of the world’s population. That such a policy has never existed is apparently by the by when it comes to such appeals to western ‘victimhood’.

As well as being denied access to global wealth at home, foreigners should obviously, Mason argued, be prevented from seeking it within Britain’s borders. Rather than seeking to extend freedom of movement to those beyond Europe’s borders as a basic right of the international working class, Mason sought to abolish it altogether, arguing after the Brexit vote in June 2016 that “the Labour front bench must commit to staying inside the single market, while seeking a deal on free movement that gives Britain time and space to restructure its labour market.” This formula – of maintaining the capitalist free market but ending freedom of movement for European workers – was exactly the same as that sought by the Tory Brexiteers, and had long been ruled out by the EU itself. He went on to bemoan the fact that John McDonnell’s ‘red lines’ on Brexit had not included the demand to end free movement. For Labour’s Brexit plans to “embody the spirit of the referendum,” he argued, the party needed to push for a “significant… retreat from freedom of movement. That means – and my colleagues on the left indeed to accept this – that the British people, in effect, will have changed Labour’s position on immigration from below, by plebiscite.” Only an anti-immigration policy, he argued, would avoid electoral disaster.

One time pro-Corbyn economist and leading tax reform campaigner Richard Murphy agreed. His post-Brexit broadside against the leadership suggested that migrants should only be allowed into the hallowed heartland of whiteness if their home country had taken on the entirety of the expense of training them for the purpose: “Learning English, offering a skill and being willing to work where work is needed can be and should be the conditions of seeking to live in this country. Migration would be a contract, not a right,” he insisted, adding that “Norway has done this; so should we.” This was the logic of apartheid influx control – “ministering to the needs of the white man” – writ global. Like Mason’s position, this was and is no different from the policy of the Tory right.

Mason and Murphy’s blows clearly landed. When the Immigration Bill – which cranked up the ‘hostile environment’ for irregular migrants by effectively turning landlords, banks and universities into extensions of border patrol – had passed through parliament the month before the Brexit referendum, Corbyn had led the parliamentary opposition, with 245 MPs ultimately voting against it. Whilst not enough to prevent the bill becoming law, this was still major progress compared to the 6 Labour MPs (including Corbyn himself) who had voted against its 2014 predecessor which had formally ushered in the ‘hostile environment’. Yet this principled position would not last. Whilst Mason was correct that MacDonnell’s initial red lines, formulated in the days after the referendum, had not included immigration controls, a week later, on 1st July 2016, MacDonnell clarified his position: “Let’s be absolutely clear on the immigration issue. When Britain leaves the European Union, free movement of labour and people will then come to an end.” In March 2017, Corbyn’s shadow Brexit secretary Kier Starmer formalised this as an official condition that would have to be met for Labour to support any Brexit deal in parliament (‘Does it ensure the fair management of migration in the interests of the economy and communities?”), effectively a sixth ‘red line’. Later that year, Corbyn himself appeared to have been won over to the benefits of blaming migrants for wage cuts and working conditions, arguing on the Andrew Marr show against the “wholesale importation of underpaid workers from central Europe in order to destroy conditions in the construction industry”. Commented Zak Cope: “By feeding the grossly one-sided view that globalisation has been disastrous for British workers, by blaming high immigration levels for stagnant wages, and by studiously ignoring Britain’s role as a parasitic drain on the countries of the Third World, Corbyn’s social democratic nationalism has inadvertently (?) legitimised and promoted a self-pitying, white nationalism that has seen a rise in racist hate crime in the UK. In purporting to oppose this upsurge in popular xenophobia and racism, however, the British left (and its European and US counterparts) is indulging in rank hypocrisy.”

The Labour manifesto of the following year, drafted by privately-educated Cambridge graduate Andrew Fisher, would again state that “freedom of movement will end when we leave the European Union” committing the party instead to supporting the “management of migration”. As Fisher later explained, “Taxing the rich, public ownership of the railways and core utilities, and ending austerity had majority public support. Increasing benefit levels and more humane migration policies did not.”

The 2017 manifesto, in fact, was a fully-fledged return to the heyday of social imperialism. Corbynism had now been shorn of any remnants of anti-imperialism (a concept mocked by leading lights of the campaign such as Paul Mason), and was now wholly committed to the military apparatus required for the enforcement of colonial wealth transfer. The document committed Labour to meeting NATO’s requirement to spend 2% of GDP on the military, and praised Tony Blair’s government for consistently spending above this benchmark, whilst criticising the conservatives for cuts to the number of aircraft carriers and jump jets in the British arsenal. It committed itself to not only retaining, but renewing, the Trident nuclear defence system (estimated costs of which vary from £39 to £205billion), and to ensuring “our conventional forces are versatile and able to deploy in a range of roles.” Why they should be “deployed” at all, rather than simply maintained as a defensive force to protect against invasion, was never explained; nor was there any mention of the seven wars in which British troops were deployed at that very moment.

The electorate appeared to like it; Labour did far better than expected in the 2017 election, increasing their vote share to 40%, up 10% from the 30% they had achieved under Ed Miliband’s leadership just two years earlier, the biggest swing for any party since 1945. This gave them a net gain of thirty seats, enough to wipe out the Conservative’s majority, and a clear electoral vindication for the party’s social imperialist platform. There was euphoria in the Corbyn camp – and gloom amongst the Blairites, who had hoped to use a disastrous showing for the party to finally rid themselves of their upstart leader. Yet the results obscured some serious warning signs. Across 41 seats in Labour’s former industrial heartlands of the North and the MIdlands – seats that later became known as the ‘Red Wall’ – the Conservative’s vote share increased to 42%, higher than Labour’s national average. Although Labour managed to hang on to most of these seats, six of them fell to the Conservatives. These were constituencies that had been Labour strongholds for, on average, over fifty years, yet now they had done the inconceivable and returned Tory MPs. The taboo had been broken.

Focus groups run by the Conservative peer Lord Ashcroft in the aftermath of the 2017 election revealed that, whilst Labour’s anti-austerity message was popular, many voters remained suspicious of Corbyn’s commitment to the defence of British supremacy abroad. Commented Ashcroft, “Lifelong Labour voters would often say that Jeremy Corbyn was the single biggest reason they were reluctant to stay with the party.” The first set of reasons for this all related to his colonial credentials, with voters making comments like “He’s anti-military. He wants nuclear submarines without the nuclear missiles. How stupid can that be?”; “It’s disastrous, his stance on defence, potentially catastrophic;” “He had links with the IRA. I didn’t like that at all;” “‘He was supporting the IRA. He was turning up at gunmen’s funerals.”

Yet “more often,” wrote Ashcroft, “people simply did not think he was up to the job of leading the country.” Voters explained that they found Corbyn “wet,” “weak,” “too principled,” too lacking in “balls”, and, revealingly, “the most humanitarian of all our politicians…But that could be our problem with Corbyn. He’s just going to give it all away.” What both sets of reasons have in common is that they all relate to the fear that Corbyn, however much he attempted to distance himself from his former principles, simply could not be trusted to “stand up for British interests”. When it came to the bottom line, Corbyn’s willingness to defend the flow of wealth to Britain from the global South, and maintain exclusive native British access to it, was seriously in doubt. The media, and the Conservatives, had found the crack in Corbyn’s armour and were determined to explode it.

Labour has for some time been a fragile electoral coalition of two main constituencies – an older, more ‘culturally conservative’ and nationalist constituency in the former industrial towns of the North and Midlands, forming the core of the Leave vote; and a younger, more socially liberal and multiethnic constituency based in the big cities, forming the core of the Remain vote. The claim of ‘anti-semitism’, which dominated coverage of the Labour leader for the next two years, was particularly well chosen to undermine Labour’s support amongst both. On the one hand, it was clearly an accusation with which the socially liberal metropolitans did not wish to be associated with, demoralising them and undermining their belief in the Corbyn project. But on the other, the Israel-Palestine conflict served as a neat proxy for the growing fears of ‘white decline’ rapidly gaining currency on the anti-immigrant right. By drawing attention to Corbyn’s support for Palestine, the media were able to successfully associate him with the Muslim Other in the great battle for civilisation. The realisation of the ‘right to return’ which he (along with longstanding international law) supported, so the fear went, would lead to the ‘swamping’ of white Israeli civilisation by brown-skinned Arabs. Was this Corbyn’s vision for Europe as well? The implication did not need to be spelt out – the visuals of the conflict said it all – but it is revealing that one of the most vociferous purveyors of the anti-semitism smear, Lord Sacks, was also a strong supporter of Douglas Murray, the acceptable face of white decline/ great replacement catosrophism. For those who already suspected Corbyn of being an Arab-lover, the anti-semitism crusade, by keeping the focus on Corbyn’s position on Palestine, was a constant reminder of his reluctance to stand up for global white supremacy, defeating all the Corbyn camp’s attempts to keep foreign policy off the agenda and out of voters’ minds. Corbyn himself – much to the despair of an increasingly exasperated John MacDonnell – also helped to keep the issue alive, by refusing to budge from the Palestinian position of wariness towards the two most controversial ‘examples’ of anti-Semitism that the Labour party was being pressured to adopt, both of which were seen as potentially being abused to delegitmise criticism of Israel. In the end, Corbyn capitulated and adopted them anyway – but not until, argue Gabriel Pogrund and Patrick MacGuire, all the political capital achieved by the election result had been used up in the failed attempt to resist doing so.

Nevertheless, at the start of 2018, Corbyn’s poll ratings remained significantly above those of Theresa May. What would change this, permanently, was Corbyn’s response to another test of his ‘patriotism’ – the poisoning of the Skripals. In March 2018, Julia and Sergei Skripal, visiting the UK from Russia, were rushed to hospital having been discovered unconscious and foaming at the mouth on a bench in Salisbury, apparent victims of a nerve agent attack. Foreign Secretary Boris Johnson was quick to blame Putin, and used the incident to intensify the ongoing war of attrition against the Russian state, cajoling other countries to embark on a worldwide expulsion of Russian diplomats unprecedented even at the height of the Cold War. Rather than close ranks behind the government’s sabre-rattling, however, as ‘loyal oppositions’ are clearly expected to at such times of ‘national crisis’, Corbyn dug his heels in and suggested that blame and retaliation should await the production of convincing evidence and that internationally agreed procedures should be adhered to. It was a position of political suicide in a country used to throwing its weight around. “That’s fucking going to cost us the election!” fumed John MacDonnell’s media advisor James Mills following a press conference in which Corbyn’s press secretary Seamus Milne questioned the undisclosed intelligence reports that the government was using to justify its actions; “Who the fuck does stuff like that?” (Pogrund and MacGuire, p.80). Certainly not Corbyn’s social democratic forebears – as Pogrund and MacGuire have pointed out, “as much as the left had lionised Attlee and Foot, both had supported military action by their Conservative opposite numbers” when it came to the crunch.

The incident was a tipping point, not only in terms of Corbyn’s public standing and the, already corrosive, division between his team and the parliamentary party – but also for relations within the Corbyn camp itself. Not only Emily Thornberry – always a fairweather friend of the project – but more significantly, Dianne Abbott and John MacDonnell, Corbyn’s only longstanding comrades in the parliamentary party, began to go consistently off-message when it came to Russia. The defence of Putin – even against accusations which appeared, at least at first, to be unfounded – was not the hill MacDonnell had been working thanklessly for decades to die on. His relations with Corbyn’s office were irreparably damaged.

Corbyn would try to make amends and demonstrate his (white) nationalist credentials a year later when the next instalment of the ‘hostile environment’ came before parliament, in the form of the government’s new Immigration Bill. This bill established Britain’s new post-Brexit migration policy, creating a new income qualification for migrants, introducing a ‘cap’ on migration, and barring all new migrants from accessing public funds or settling permanently. The aim was to end freedom of movement for low-paid workers whilst maintaining it for middle class professionals, and to ensure that any migrants who did make it into the country were in a position of permanent precarity. It was clearly a ferociously anti-working class piece of legislation (except for the most myopic and nationalist definitions of ‘working class’). This was, in fact, recognised by Dianne Abbott, Corbyn’s shadow Home Secretary, who wrote that, under the new legislation, “many migrant workers who come to Britain will in effect have no rights” and called it “one of the most serious threats to all workers for decades…The risk of super-exploitation will be built into the legal system.” Yet when it came to the first parliamentary vote on the bill, the position of the ‘worker’s party’, under its ‘pro-migrant’ leader, Corbyn, was, right up until three hours before the vote, to abstain; as Abbott herself noted, defence of Freedom of Movement was incompatible with the party’s 2017 manifesto, to which she declared herself a “slavish devotee” and therefore duty-bound to let the bill pass at its second reading. This official position of abstention was, at the very last minute, changed to advice to vote against the bill – but only after many MPs had already left parliament for the day. Yet even this about-turn was half-hearted, backed only by a ‘one-line whip’, the very weakest type of enforcement, with no consequences for insubordination – and in stark contrast to the three line whips with which Corbyn used to enforce support for Theresa May’s early Brexit votes. As a result, 78 Labour MPs were absent when the vote was called, and the bill passed by a margin of 63. Corbyn had helped the Tories deliver, in Abbott’s words, “one of the most serious threats to all workers for decades”. Yet there was no popularity dividend amongst the Leave-voting anti-migrant constituencies he was presumably trying to woo, and his ratings remaining as stubbornly low as ever.

The problem for Corbyn was that he never quite managed to convince people that he had left his old anti-imperialist and pro-immigrant views behind; and his reluctance to ditch the Palestinians or jump on the Russia-baiting bandwagon buried any chance he might have had of doing so. By the time the 2019 election came around, this was clearer than ever. As Luke Pagarani wrote after 100 hours of canvassing, “the key charge against Corbyn is that he fundamentally believes British lives are of equal value to the lives of others,” an unacceptable position for the bulk of the British electorate. His continued: “His opponents wouldn’t put it so bluntly, but this is what it has always been about. Hence the series of confected outrages – from not bowing deeply enough at the Cenotaph to ruling out pushing the nuclear button – that built a treasonous charge sheet as absurd as it was banal. Smears such as Corbyn “siding with Putin” over the Salisbury poisoning, when caution about trusting the judgment of British intelligence agencies was cast as support for the Russian version of events, or “supporting” the IRA, gained more traction as time went on. Even Corbyn’s commendable record of campaigning against the geopolitical grain, such as for dispossessed Tamils, Chagossians and Palestinians, came to be seen as evidence that he didn’t know which side he was supposed to be on. A symbolic moment of the campaign was the first leaders’ debate, when Corbyn highlighted the impact that the climate crisis would have on the poorest people in the world and a section of the audience responded with groans and someone shouted, “Here we go again!” When people talk about having paid into the system all their lives, as I heard repeatedly at the doorstep, they’re not just talking about national insurance payments and the benefits they’re entitled to. They’re talking about loyalty to a state they expected to be their exclusive patron …A small hoard has been salvaged from the UK’s long post-imperial decline, and only those whose fealty is proven can claim their share…Taxing the rich was unpersuasive, as many people just thought it impossible. These voters wanted the patronage of the powerful, not to challenge their power.”

The Conservatives, meanwhile, had learnt their lessons from the 2017 election very well. The first was that austerity was not a votewinner. The public sector pay cap – Labour’s opposition to which, according to Ashcroft’s research, had been “one of [their] biggest attractions, which our respondents raised spontaneously throughout the campaign” in 2017 (Ashcroft, p.26) – had been ended by the Conservatives a few months before the election (only to be reimposed again less than a year after), removing one of the major grievances against them of the previous election. And in sharp contrast to Theresa May’s unremittingly grim spending propositions in 2017, Boris Johnson went to the electorate with a promise of more nurses, more police and more hospitals.

The second lesson was that, in 2017, the electorate had not been quite ready to buy Theresa May’s claim that parliament, and Labour in particular, was obstructing Brexit. But two years of Brexit quagmire in a hung parliament now meant the argument had far more traction (that Johnson himself had led the opposition to getting May’s Brexit deal passed was apparently a nuance with which the electorate were not concerned).

Combined with Labour’s eleventh hour conversion to a rerun of the Brexit referendum, the proposition in 2019 was now fundamentally different to that of 2017. Back then, an electorate seeking to move past Brexit and end austerity faced two Brexit-supporting parties, only one of whom was offering to end austerity; now, they seemingly faced two parties seeking to end austerity, only one of whom was offering to ‘get Brexit done’. More fundamentally, however, they also faced a Labour party whose commitment to upholding the colonial balance of power on which their globally-privileged living standards depended was in doubt as never before. Because, as in 2017, former Labour voters consistently gave not Brexit but Corbyn as the main reason for changing their vote – ”usually justified,” noted Jeremy Gilbert, “with reference to Corbyn’s supposed historic sympathy for the IRA or his ‘excessive’ sympathy with Muslims.”

In the end, all post-mortems of the Corbyn project must answer two questions. The first – could any policy platform or leader have won the 2019 election for Labour in the circumstances? The fact that Labour’s two main electoral constituencies – the culturally conservative former industrial towns of the North and Midlands, and the socially liberal multiethnic communities of the large cities – had by this point hardened into seemingly irreconcilable identities based on ‘Leave’ and ‘Remain’ makes it hard to be positive on this front. This is especially so given that Labour seem to have lost around a million voters on the Leave side, and 1.7million on the Remain side, suggesting that more decisive movement in either direction would only ever have traded lost votes rather than saved them.

But the more important question for socialists is could Corbyn – or anyone with the politics he represents – have won in any circumstances?

Ultimately, the fate of Corbynism was defined by a series of tragic realities, three of which were beyond the project’s control, and the last of which resulted from a stubborn unwillingness to recognise the first three.

The first is that the vast majority of the British population are, at least on an immediate material level, beneficiaries of the global system of racialised capitalism with, therefore, no class interest in upending the neocolonial status quo. The electoral base necessary to deliver a parliamentary victory for any kind of anti-imperialist programme in this country, then, simply does not exist. As Zak Cope has argued, “Britain and all of the classes and class fractions therein (albeit to varying degrees) are net consumers of value created elsewhere [and this] fundamentally bourgeois class structure of Britain means that there is no mass basis for British people to act as agents of change.” The country has “a right-wing electorate that fears above all the dissolution of [global] white supremacy as a condition of its caste-class status.” Capitalism is a system of global exploitation of which the entire populations of Western nations are net beneficiaries, and, in the main, they know it; the citizens of the imperial states are aware not only that their living standards are relatively privileged by global standards, but are also on some level aware, I would contend, that this privilege is dependent on the continued impoverishment of the global South. As Cope has written, “It is obvious that the wage in Guatemala or China is only a fraction of the wage in first world countries. It is equally clear that there is a connection between low prices for bananas, coffee and electronics and the low wages paid to the workers that produce them…No doubt the average person is unaware of the theory of unequal exchange as such, but a great many people in the first world are aware that they buy goods cheap relative to the labour that goes into their production.” Western citizens, in other words, know which way their bread is buttered.

This need not have been a fatal blow for the Corbynite project, however – which, as we have seen, quickly defined itself as an overtly social imperialist programme. Says Cope, Corbyn “promotes a national chauvinist version of socialism that aims to share among the British people more of the wealth accumulated through Britain’s imperialist exploitation of dependent countries…[Whilst] he has been a fairly consistent long-term critic of neoliberal restructuring of Britain’s welfare state… neither he nor his supporters have concerned themselves with stopping the flow of surplus value from the Third World. Doing so would require an end to British economic and military imperialism, that is, the radical restructuring of British society as we know it,” something the 2017 manifesto made clear it was not prepared to countenance. A party which had been more immediately and convincingly willing to toe the line of the imperialist bourgeoisie on Palestine and Russia may well have been able to garner support for a more equitable national distribution of imperial loot. Whether they could do this under a leader with a track record such as Corbyn’s, however, is far less likely. The second tragedy for the Corbynites, then, was that, despite the project’s capitulations, the colonial credentials of Corbyn himself, thanks to his track record of involvement in the anti-war, anti-nuclear, and international solidarity movements, were so much in doubt that he would never be trusted, by either the electorate or the elite, to be allowed into office. As Cope put it, “Corbyn is neither sufficiently xenophobic nor racist enough to appeal to the white working class electorate, and he is neither militarist enough nor neoliberal enough to gain the backing of the financial elite.” It is not only commitment to the basic principles of imperialism (if not necessarily their every manifestation) that is a necessary condition of electoral success in imperialist countries; that commitment must be seen to be sincere. This was not something Corbyn could ever have achieved.

Even a hypothetical scenario in which a 2017-style social imperialist programme achieved electoral victory under a leader with an unimpeachable track record of disdain for Third World struggles, however, would not necessarily result in the realisation of that programme. For the third tragedy of the Corbyn project is that whilst there may still be an electoral base for a social democratic programme in Britain (so long as it does not challenge neo-colonialism), what does not exist are the class forces required to enact it once in office.

Quite apart from the colonial credentials he established during his five years service as Churchill’s deputy in the War Cabinet, overseeing, amongst other atrocities, the Bengal famine and the bombing of Dresden, Attlee was allowed to deliver his left-economic programme due to a quite unique constellation of circumstances in 1945. First of all, capitalism was under threat as never before, primarily due to the existence of the Soviet Union, which emerged from the Second World War with its prestige at an all time high. Not only was it universally acknowledged to have been by far the major force in the defeat of Nazi Germany, but it seemed to have been the only industrialised nation to have got through the 1930s without being plunged into an economic depression. It suffered many other problems during this time, of course, to put it mildly; but the worst of them were not yet known to the rest of the world, much of which viewed Soviet socialism as a far superior system to the global capitalism that had failed so miserably in the 30s, ushered in fascism and led to two world wars. Capitalism, in other words, had an existential need to prove itself, as, unlike today, it faced a seemingly viable – and powerful – alternative.

In addition to these favourable geopolitical circumstances, British capitalism faced a domestic working class movement that was heavily unionised, politicised and militarily experienced – a powerful combination, with no equivalent today. In addition, the mass destruction of the war meant that there was a high demand for labour, giving the unions major leverage they do not have today, as well as a need for government investment in bankrupted industry. And finally, British capital was far less footloose than it is today; had it opposed the new settlement, it would have had nowhere else to go anyhow. In sum, in 1945, the capitalist class themselves were pushing for a new dispensation that would simultaneously get industry back on its feet, underwrite a more quiescent working class and deal with capitalism’s image problem.

None of this pertains today. In our hypothetical scenario, the most likely outcome of any attempt to deliver a social-democratic programme such as that promised by Labour under Corbyn would be that the financial markets would simply strangle the economy into submission. In this regard, the voters’ oft-repeated scepticism towards Labour’s ability to deliver on its manifesto promises must be seen not only as a reflection of cynicism towards ‘lying politicians’ but a rather savvy understanding of the class forces ranged against such an undertaking. Voters were essentially correct that Labour’s economic programme was unachievable – not because the ‘money was unavailable’ – the country is awash with cash, which was the main cause of the 2008 crisis – but rather because of the inevitable resistance of the bourgeois financiers.

Given the structural impossibility of challenging neo-colonialism at the ballot box and the virtual impossibility of delivering even social democracy in contemporary conditions, the real tragedy of Corbynism is that its commitment to delivering these undeliverables blinded the project from realising what could have been achieved. Corbyn’s election to the leadership in 2015 and the upsurge of enthusiasm it ignited presented a unique opportunity to use the organisational capacity of the Labour party to create cadres of community activists committed to meaningful and effective grassroots mobilisation. With 600,000 members, Labour was the biggest political party in Europe by membership, and even the internal left pressure group Momentum had 50,000 members, opening up the possibility of creating a real and lasting counterforce of working class power. Imagine what could have been achieved had these enthusiastic members been put to work in the most alienated and neglected communities, organising grassroots local campaigns, political education, youth programmes and breakfast clubs. Of course, there is a danger that such work would have been perceived as patronising or condescending – especially if it were to involve young middle class city folk (who seem to have been the core of the new Labour membership) descending on areas with which they have no organic connection. They would have had to have been organised by locally-rooted, experienced activists, and would have had to have serious training in the culture and ethos of the local communities they would be serving – and, even then they would have had to have worked hard to overcome much entrenched (and justified) suspicion. But none of this would have been beyond the organisational capacity of the Labour party; indeed, Labour, with its deep roots in the unions and working class movement, was and is uniquely positioned to organise such an endeavour. Yet the chance to use that position to actually build working class power in the communities was squandered. Such power would not have been enough to have won the election, for all the reasons outlined in this piece. But that is not the point; the point is to build – both through organisational practice and political consciousness raising – the power of the working class movement, as a detachment of the international proletariat. In the end, all attempts at grassroots mobilisation, political education, community programmes, and anti-militarism were ultimately subordinated, it not completely sacrificed, to the priority of winning the election. This was the real tragedy of Corbynism.

[Dan Glazebrook is a political commentator and agitator. He is the author of Divide and Ruin: The West’s Imperial Strategy in an Age of Crisis (Liberation Media, 2013) and Supremacy Unravelling: Crumbling Western Dominance and the Slide to Fascism (K and M, 2020). Article courtesy: CounterPunch.]