Sudheendra Kulkarni

(Article being published to commemorate Lokmanya Tilak’s 100th death anniversary on August 1.)

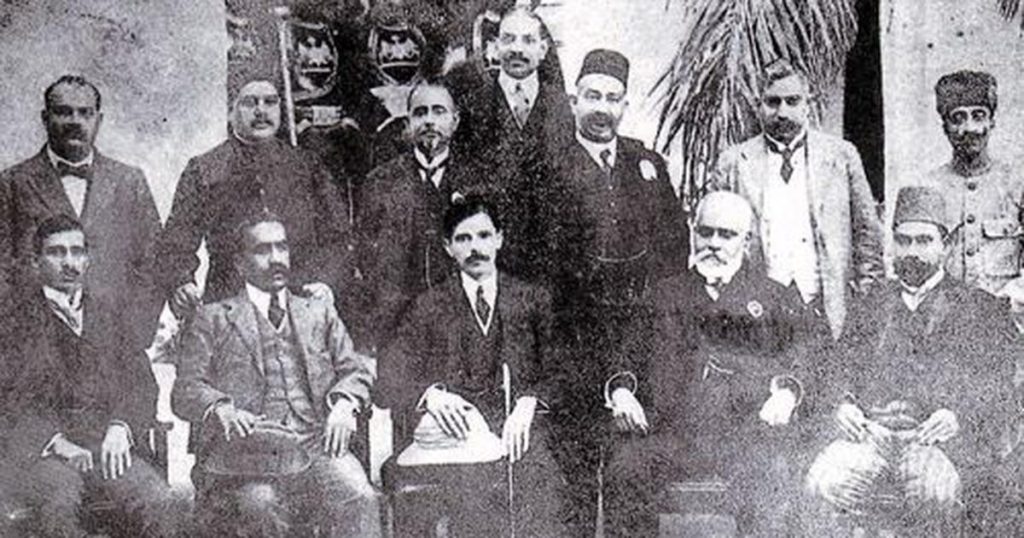

When we look back at India’s freedom movement, we see two milestones when Hindu-Muslim cooperation reached its zenith. One was the 1857 War of Independence, when the two groups fought shoulder to shoulder against “Company rule” – the colonial advancements of the East India Company – from Peshawar to Dhaka. The other was the Lucknow Pact between the Congress and the Muslim League in December 1916, whose principal architects were Lokmanya Bal Gangadhar Tilak and Mohammed Ali Jinnah.

How did such a remarkable pact between two apparently dissimilar parties, which would be unthinkable in today’s highly-polarised and intolerant atmosphere, happen? For any major breakthrough to happen in politics, two propitious developments, one objective and the other subjective, have to come together. There has to be a turn in the external circumstance conducive for a bold move to be made. There also has to be an internal resolve among leaders to conduct a new experiment.

The outbreak of the First World War in 1914 created such a situation, which made the British government seek cooperation of Indian public and political parties in its war effort. This naturally entailed a willingness to give some concessions in the form of constitutional reforms.

Around the same time, a few highly significant changes had taken place in the political situation in India. Tilak had been released in 1914 after he completed his six-year imprisonment in Mandalay, Burma, after being convicted in a sedition case in 1908. The following year, he was re-admitted into the Congress.

Thus, the bitterness of the split in the Congress between the “extremists” and “moderates” at its 1907 session in Surat was now a thing of the past. Tilak had emerged as an even more popular and respected leader of the Congress because of his imprisonment. The prolonged prison experience had further steeled his belief that Hindu-Muslim unity was a pre-requisite for the advancement of the Indian demand for Swaraj. He also concluded that Britain’s deep involvement in the First World War had opened a new window of opportunity to seek constitutional reforms for self-rule.

The 1916 Lucknow pact

Around the same time, in 1913, Jinnah had finally joined the Muslim League. Remarkably, he continued to be a member, simultaneously, of the Congress, which he had joined in 1906. He was held in high esteem in both Congress and Muslim League circles, and was popularly known as an “ambassador of Hindu-Muslim unity”. Tilak and Jinnah had already worked together in the previous decade. Hence, a confluence of India’s two main political streams led to the historic Lucknow Pact in 1916.

More by design than by coincidence, the annual sessions of the Congress and the Muslim League took place around the same time, in the last week of December 1916, in Lucknow. Jinnah was elected president of the Lucknow Muslim League session. Even though Ambika Charan Mazumdar became the president of the Congress session in that year, Tilak was the prime mover of the pact with the Muslim League. Significantly, the Home Rule League founded by Annie Besant, in which both Tilak and Jinnah were members, also held its session in Lucknow at the same time.

The highlight of the Lucknow Pact was that the Congress and the Muslim League agreed on separate representation to Muslims and gave due weightage to their representation, higher than their percentage in population would warrant, in the Imperial/Provincial Legislatures where they were in a minority. At the same time, applying the same principle, it increased the representation of non-Muslims and suitably reduced the representation of Muslims in the Muslim-majority provinces like Punjab and Bengal. As a result, the pact conceded to the Muslims one-third of the seats in the Imperial Legislative Council.

In Bengal, where Muslims constituted 52.6% of the population, their legislative representation was reduced to 40%. In Punjab, where they constituted 54.8% of the population, their legislative representation was limited to 50%.

In the Muslim-minority provinces, the pact gave concessions to Muslims in provincial legislatures. For example, Muslims constituted 10.5% of the population in Bihar and Orissa, but got 25% of the seats in the legislature. In Bombay they constituted 20.4% of the population but got 33.3% of the seats in the legislature. In the Central Provinces, their share in the population was 4.3%, but they got 15% of the legislative seats. In Madras, they accounted for 6.5% of the population, but got 15% of the legislative seats. In the United Provinces – modern-day Uttar Pradesh – their share of the population was 14%, but they got 30% of the legislative seats.

Furthermore, the Pact introduced another safeguard to reassure both communities. No proposal that affected any one community could be passed in legislatures if three-fourths of that community’s representatives were opposed to it.

The idea of separate electorates sounds odd, even repugnant, in today’s India. So does the seemingly undemocratic concept of over-representation to a religious community – to Muslims in Hindu-majority provinces and to Hindus in Muslim-majority provinces. However, we have to view this agreement from the point of view of the conditions prevailing in India in the second decade of the last century.

Its chief gains were two-fold. First, India’s two main political parties agreed to work together. Second, it provided a higher stake for the minority community to share power with the majority community, thus addressing the concerns of both Muslims and Hindus.

Triangular vs two-way struggle

It is worth emphasising here that neither Tilak nor Jinnah was the originator of the idea of separate electorates. The Indian Councils Act 1909, also known as the Morley-Minto Reforms, had conceded the Muslim demand for separate electorates in its highly restricted devolution of power to Indians. This was opposed by the Congress, which was in favour of joint electorates. At the same time, there was realisation in large sections of both the Congress and the Muslim League that a united front of Hindus and Muslims was necessary to move towards meaningful self-governance.

Tilak best represented this new thinking in the Congress and spoke effectively in favour of the party’s session in Lucknow endorsing separate electorates for Muslims and other provisions in the Pact. Leaders like Pandit Madan Mohan Malaviya, BS Moonje and Tej Bahadur Sapru opposed him, saying he had surrendered to the Muslims by conceding the “anti-national and anti-democratic” system of separate electorates.

However, Tilak’s arguments carried the day for two reasons. First, he was the most devout among all the Hindu leaders in the Congress, and also the most learned in the Vedas. Therefore, his Hindu credentials could not be doubted. Second, in the early years of his public life, he was not really regarded as a friend of Muslims. Therefore, the Muslim community welcomed what it felt was a genuine change in his thinking. Interestingly, it was also a volte-face for Jinnah since he was previously opposed to separate electorates for Muslims.

In Lucknow, Tilak staked his all for the Hindu-Muslim settlement. Addressing over 2,000 delegates in the open session, and using words that only a leader with enormous conviction and self-confidence can, he said: “It has been said that we, Hindus, have yielded too much. The concession that has been made to our Mohommedan brethren in the Legislative Council is really nothing too much. In proportion to the concession that had been made to the Moslems their enthusiasm and warm-hearted support is surely greater. I urge the audience to give effect actively to the resolution adopted by the Congress.”

Explaining his stand further, in his address at the concurrent session of the Home Rule League in Lucknow, Tilak remarked: “There is a feeling among the Hindus that too much has been given to the Muslims. As a Hindu I have no objection to making this concession. When a case is difficult, a client goes to a lawyer and promises to pay him one-half of the property if he wins the case. The same is the case here. We cannot rise from our present intolerable condition without the aid of the Muslims. So in order to gain the desired end there is no objection to giving a percentage, a greater percentage, to the Muslims. Their responsibility becomes greater, the greater the percentage of representation you give to them. They will be doubly bound to work for you and with you, with a zeal and enthusiasm greater than ever. The fight is at present a triangular one.”

Tilak’s stand was that the “triangular” fight among Hindus, Muslims and the British should be reduced to a “two-way” fight between the British and the common front of Hindus and Muslims. And for bringing about this fundamental change, he was prepared to show that Hindus were willing to be magnanimous towards their Muslim brethren, who, after all, were fellow Indians. What was important was for the Hindus and Muslims to sink their differences in the united struggle for Swaraj.

The Congress-Muslim League entente in Lucknow had created such an amiable inter-communal atmosphere that Tilak was invited to attend the session of the Muslim League on December 31st. “He was accorded the warmest reception and the grandest ovation,” writes his biographer DV Tahmankar.

There is also an eye-witness account by Dr Mukhtar Ahmed Ansari, one of the founders of Jamia Milia University in Delhi, who was present at the sessions of both the Congress and the Muslim League in Lucknow. “Without any doubt [Tilak’s] generous gesture was a great factor in winning over the Mussalmans… His vision was not of Hindu domination, as some people have wrongly asserted, but of a united India marching forward to attain its freedom.”

“Worthy of being written with golden letters”, is how Tilak’s newspaper Kesari hailed the signing of the Lucknow Pact. “On that day, on the banks of the sacred river Gomati the standard of Indian Swaraj was unfurled… Caste and creed distinctions, differences of opinion, personal jealousies and everything that was gross and went to destroy the unity of the nation was finally drowned in the waters of Gomati, and India assumed a new and sacred form.”

Kesari also wrote:

“The Muhammadans are not a weak-minded people. Before the advent of the British they were the rulers of Northern India and Englishmen and Marathas served them as their Dewans and Mutaliks. During a quarter of a century following the (1857) Mutiny they were under the Government’s disfavour and this treatment made them sullen and disappointed. But all the while their political aspirations remained as strong as ever, and education as a tigress’ milk naturally put new life in them. Moreover, their Khaliphate which had grown powerless has recently improved its position…. In these circumstances, and at a time when their Hindu brethren were marching forward with the times, why will the Muhammadans sit silent with folded arms? They, therefore, joined hands with the Hindus. The Hindus too showed good sense by toning down their opposition to their demands for special representation. They also consented to grant them representation in the Legislative Councils in excess of their numerical strength. The Hindus have thus given to the Muhammadans something at least for which they will be grateful. But what is Government going to give to the Muhammadans? The spirit of compromise has removed all fears of differences between the two communities and the Government should bear in mind that they will now unitedly fight with them with greater energy than before.”

In his speech at the Muslim League session in Lucknow, Jinnah similarly tried to reassure Indian Muslims – and the Indian National Congress. It’s worth repeating here Jinnah in 1916 was a member of both the Congress and the Muslim League. Indeed, on the platform of the Muslim League in Lucknow, he described himself as “a staunch Congressman” who had “no love for sectarian cries”.

Urging his fellow Muslim Leaguers not to view the Lucknow Pact from a sectarian perspective, Jinnah continued:

“It is said, and I am referring here to what my Mussalman friends say that we are going on at a tremendous speed and that we are in a minority and so might not the government of this country become a Hindu Government? I want to give an answer to it. I wish to address my Mussalman friends on that point. Do you think that in the first instance it is possible that the Government of this country can become a Hindu Government? Do you think that the Government can be conducted merely by the ballot box? [Cries of “no”]. Do you think that because the Hindus are in a majority they have therefore to carry a measure in the Legislative Council and there is an end of it? If 70 million Mussalmans do not approve of the measure which is carried by a ballot box, do you think that it could be enforced or administered in this country? [Cries of “never”.]

“Do you think that the Hindu statesmen with their intellect, with their past history, will ever think of enforcing measures by the ballot box when you get Self-Government? [Cries of “no].

“Then what is there to fear? [Cries of “nothing”]. Therefore, I say to my Mussalman friends: Fear not. This is a bogey, which is put before you by your enemies [Hear, hear] to frighten you, to scare you away from cooperation and unity which are essential for the establishment of Self-Government [Cheers]. This country has not to be governed by the Hindus and, let me submit, it has not to be governed by the Mussalmans either, and certainly not by the English [Hear, hear]. It is to be governed by the people and the sons of this country. I, standing here – I believe I am voicing the feeling of whole of India —demand the immediate transfer of a substantial power of the Government of the country.”

Addressing a meeting at Shataram Chawl in November 1917, Jinnah said: “My message to the Mussalmans is to join hands with your Hindu brethren. My message to Hindus is to lift your backward brother up.”

It is worth mentioning here that Jinnah regarded separate electorates for Muslims not as a permanent constitutional feature. He felt that it could be reformed with the passage of time.

Lucknow Pact was thus, the first – and, sadly, the last – formal agreement between the two major communities of India to seek constitutional reforms leading to self-governance. It was anchored in mutual trust if not among all the leaders of the Congress and the Muslim League, at least between its two principal architects: Tilak and Jinnah.

Why the pact failed

It is one of the great tragedies of India’s freedom movement that the spirit of Hindu-Muslim unity, and Congress-Muslim League cooperation, did not last the test of subsequent developments. Why did this happen? One important reason is that the Montagu-Chelmsford Reforms announced by the British government in 1919 did not respond to the key demands of Lucknow Pact at all. Instead of pinning down the government to their common demands, both Congress and Muslim League leaders got drawn into responding – in discordant voices – to the provisions of the Montagu-Chelmsford Reforms.

The other major reason was the emergence of Mahatma Gandhi on the political scene. He had not played a major role in the deliberations of the Congress session in Lucknow, although he did not oppose the pact either. However, from 1919 onwards, he began to play a dominant leadership role in the activities of the Congress, giving the national liberation movement a distinct character of nonviolent mass agitation. This was evident in the Non-Cooperation Movement he launched in 1920. Tilak was no longer alive and Jinnah developed serious differences with Gandhi over the mass agitational methods to be adopted to achieve freedom. He also opposed Gandhi’s support to the Khilafat movement, which the former believed would cement the bonds of Hindu-Muslim cooperation. The differences were so serious that Jinnah quit the Congress party in 1920.

It must be said here that although Gandhi deeply believed in Hindu-Muslim unity – and so did Jinnah – he never made the specific demands of Lucknow Pact the basis of his subsequent politics. Is it because he did not believe in the very principle of separate electorates for Muslims? This is very likely.

Gandhi feared that this would to lead to demands by more religious communities, including castes within the Hindu society, for separate electorates. He indeed went on a fast unto death in 1932, while he was lodged in Yerwada Jail in Poona, to protest against the British government’s Communal Award, in response to Dr Babasaheb Ambedkar’s demand that granted separate electorates to “Untouchables” or Depressed Classes. He agreed to break the fast only when Ambedkar agreed to drop the demand.

There is yet another reason why Lucknow Pact became a non-starter. After 1916, Tilak did not live long enough to give a practical shape to its contents. Jinnah on the other hand was finding himself sidelined in the Congress party. Moreover, his two key supporters in the Congress – Gopal Krishna Gokhale and Pherozeshah Mehta, both moderate leaders who believed in the path of constitutional reforms – had passed away in 1915.

His hopes of the Hindu leaders in the Congress willing to share power with Muslims and the Muslim League in a self-governing India started fading. And they received a body blow when Jawaharlal Nehru, who was then the Congress president, refused to share power with the Muslim League after the Congress swept the elections to the provincial legislature in UP in 1937. Thereafter, there was little trust left between the two parties. And with growing mistrust, and with little cooperation, the Congress and the Muslim League together led India towards its bloody partition in 1947.

This tragedy happened because Tilak’s prescient endeavor to transform the “triangular” fight – Hindu vs British, Muslim vs British, and Hindu vs Muslim – into a direct two-way fight –Hindu-Muslim joint front vs British, which he had accomplished in Lucknow in 1916 – came unstuck after his demise. The fight once again became “triangular” with cataclysmic consequences.

Why its spirit should be revived

The kernel of the Lucknow Pact lay in how Tilak had understood Indian nationalism to be. As we have seen earlier, in his speech on “Patriotism” in Bellary in May 1905, he had said, “Patriotism must be composite. The limits [of patriotism] must be widened.”

In essence, he was saying that Indian nationalism was a composite whole of Hindu and Muslim communities. For achieving a larger national goal, both communities should display a spirit of compromise and mutual accommodation. This, indeed, was the spirit of the Lucknow Pact, which Tilak had so courageously articulated in his speech at the Congress session. When he was criticised for “selling out” the interests of the Hindus, he went to the extent of asserting that he would rather see the British hand over the governance of India to Indian Muslims, or Indians of any caste, than see the British remain as India’s paramount colonial authority.

Now, the question arises: Is the spirit of the Lucknow Pact still relevant, a hundred years later? The answer is most certainly yes.

The content of the Tilak-Jinnah Pact is no longer relevant, but its spirit most certainly is.

The issue of separate electorates for any religious community has become completely invalid after India became free and adopted the Republican Constitution with secular democracy as its foundation. There are no community-based separate electorates in Pakistan either. The situation in Pakistan is not really comparable to the one in India since non-Muslims have been reduced to a minuscule minority in that country. India also does not have religion-based reserved seats either in Parliament or in state legislatures.

Hence, the specific provisions of the Lucknow Pact are irrelevant today.

However, the basic motivational principle behind the pact – namely that the two main communities of India should not only peacefully and cooperatively coexist but also show the readiness to compromise should the need arise – is valid even today. It is valid for inter-communal relations within post-1947 India. It is also valid for India-Pakistan relations.

Both Tilak and Jinnah, if they were alive today, would have been deeply distressed at the current state of India-Pakistan relations and also at the inter-community relations within our two countries. We should also include Bangladesh here.

In particular, neither India nor Pakistan is showing any magnanimity, any constructive understanding, and any inclination to compromise in dealing with the contentious bilateral issues. Let us be honest: can the dispute over Kashmir be ever resolved through bilateral negotiations without mutual trust, an attitude of give-and-take, and a commitment to justice and fairness? Are India and Pakistan to regard each other as permanent enemies? And if our hostilities continue forever, will our freedom and unity not be weakened, even endangered, with the interference of outside powers?

Another question: Has Indian nationalism ceased to be “composite”, as Tilak had believed it to be, after 1947? Is the concept of, and demand for, India as “Hindu Rashtra” consistent with Tilak’s vision of India?

If we ponder over these questions, we begin to realise that the greatest triumph of Tilak’s life lies in what turned out to be a failure – the Lucknow Pact. The Tilak-Jinnah Pact failed, but not its spirit. For this spirit alone can help in the fruition of two all-important challenges before India and Pakistan: Hindu-Muslim harmonisation and India-Pakistan normalisation.

Therefore, the most appropriate way to remember Lokamanya, the “beloved leader of the people”, is to rededicate ourselves to the revival of the spirit that animated the incredible agreement made possible by two great Indian patriots, Tilak and Jinnah, in Lucknow over 100 years ago.

(Sudheendra Kulkarni was an aide to India’s former Prime Minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee in the Prime Minister’s Office between 1998 and 2004. As the founder of Forum for a New South Asia, he is actively engaged in efforts to strengthen communal harmony in India and also to promote India-Pakistan and India-China friendship. Article courtesy: Scroll.in.)