The Stalinist Trial of Julian Assange

John Pilger

[John Pilger gave this address outside the Central Criminal Court in London on September 7 as the WikiLeaks Editor’s extradition hearing entered its final stage.]

When I first met Julian Assange more than ten years ago, I asked him why he had started WikiLeaks. He replied: “Transparency and accountability are moral issues that must be the essence of public life and journalism.”

I had never heard a publisher or an editor invoke morality in this way. Assange believes that journalists are the agents of people, not power: that we, the people, have a right to know about the darkest secrets of those who claim to act in our name.

If the powerful lie to us, we have the right to know. If they say one thing in private and the opposite in public, we have the right to know. If they conspire against us, as Bush and Blair did over Iraq, then pretend to be democrats, we have the right to know.

It is this morality of purpose that so threatens the collusion of powers that want to plunge much of the world into war and wants to bury Julian alive in Trumps fascist America.

In 2008, a top secret US State Department report described in detail how the United States would combat this new moral threat. A secretly-directed personal smear campaign against Julian Assange would lead to “exposure [and] criminal prosecution”.

The aim was to silence and criminalise WikiLeaks and its founder. Page after page revealed a coming war on a single human being and on the very principle of freedom of speech and freedom of thought, and democracy.

The imperial shock troops would be those who called themselves journalists: the big hitters of the so-called mainstream, especially the “liberals” who mark and patrol the perimeters of dissent.

And that is what happened. I have been a reporter for more than 50 years and I have never known a smear campaign like it: the fabricated character assassination of a man who refused to join the club: who believed journalism was a service to the public, never to those above.

Assange shamed his persecutors. He produced scoop after scoop. He exposed the fraudulence of wars promoted by the media and the homicidal nature of America’s wars, the corruption of dictators, the evils of Guantanamo.

He forced us in the West to look in the mirror. He exposed the official truth-tellers in the media as collaborators: those I would call Vichy journalists. None of these imposters believed Assange when he warned that his life was in danger: that the “sex scandal” in Sweden was a set up and an American hellhole was the ultimate destination. And he was right, and repeatedly right.

The extradition hearing in London this week is the final act of an Anglo-American campaign to bury Julian Assange. It is not due process. It is due revenge. The American indictment is clearly rigged, a demonstrable sham. So far, the hearings have been reminiscent of their Stalinist equivalents during the Cold War.

Today, the land that gave us Magna Carta, Great Britain, is distinguished by the abandonment of its own sovereignty in allowing a malign foreign power to manipulate justice and by the vicious psychological torture of Julian – a form of torture, as Nils Melzer, the UN expert has pointed out, that was refined by the Nazis because it was most effective in breaking its victims.

Every time I have visited Assange in Belmarsh prison, I have seen the effects of this torture. When I last saw him, he had lost more than 10 kilos in weight; his arms had no muscle. Incredibly, his wicked sense of humor was intact.

As for Assange’s homeland, Australia has displayed only a cringeing cowardice as its government has secretly conspired against its own citizen who ought to be celebrated as a national hero. Not for nothing did George W. Bush anoint the Australian prime minister his “deputy sheriff”.

It is said that whatever happens to Julian Assange in the next three weeks will diminish if not destroy freedom of the press in the West. But which press? The Guardian? The BBC, The New York Times, the Jeff Bezos Washington Post?

No, the journalists in these organisations can breathe freely. The Judases on the Guardian who flirted with Julian, exploited his landmark work, made their pile then betrayed him, have nothing to fear. They are safe because they are needed.

Freedom of the press now rests with the honourable few: the exceptions, the dissidents on the internet who belong to no club, who are neither rich nor laden with Pulitzers, but produce fine, disobedient, moral journalism – those like Julian Assange.

Meanwhile, it is our responsibility to stand by a true journalist whose sheer courage ought to be inspiration to all of us who still believe that freedom is possible. I salute him.

(John Pilger is a renowned Australian investigative journalist and documentary film-maker.)

❈ ❈ ❈

U.S. Targets Julian Assange to Save Face

Vijay Prashad

On September 7, 2020, Julian Assange will leave his cell in Belmarsh Prison in London and attend a hearing that will determine his fate. After a long period of isolation, he was finally able to meet his partner—Stella Moris—and see their two sons—Gabriel (age three) and Max (age one)—on August 25. After the visit, Moris said that he looked to be in “a lot of pain.”

The hearing that Assange will face has nothing to do with the reasons for his arrest from the embassy of Ecuador in London on April 11, 2019. He was arrested that day for his failure to surrender in 2012 to the British authorities, who would have extradited him to Sweden; in Sweden, at that time, there were accusations of sexual offenses against Assange that were dropped in November 2019. Indeed, after the Swedish authorities decided not to pursue Assange, he should have been released by the UK government. But he was not.

The true reason for the arrest was never the charge in Sweden; it was the desire of the U.S. government to have him brought to the United States on a range of charges. On April 11, 2019, the UK Home Office spokesperson said, “We can confirm that Julian Assange was arrested in relation to a provisional extradition request from the United States of America. He is accused in the United States of America of computer-related offenses.”

Manning

The day after Assange’s arrest, the campaign group Article 19 published a statement that said that while the UK authorities had “originally” said they wanted to arrest Assange for fleeing bail in 2012 toward the Swedish extradition request, it had now become clear that the arrest was due to a U.S. Justice Department claim on him. The U.S. wanted Assange on a “federal charge of conspiracy to commit computer intrusion for agreeing to break a password to a classified U.S. government computer.” Assange was accused of helping whistleblower Chelsea Manning in 2010 when Manning passed WikiLeaks—led by Assange—an explosive trove of classified information from the U.S. government that contained clear evidence of war crimes. Manning spent seven years in prison before her sentence was commuted by former U.S. President Barack Obama.

While Assange was in the Ecuadorian embassy and now as he languishes in Belmarsh Prison, the U.S. government has attempted to create an air-tight case against him. The U.S. Justice Department indicted Assange on at least 18 charges, including the publication of classified documents and a charge that he helped Manning crack a password and hack into a computer at the Pentagon. One of the indictments—from 2018—makes the case against Assange clearly.

The charge that Assange published the documents is not the central one, since the documents were also published by a range of media outlets such as the New York Times and the Guardian. The key charge is that Assange “actively encouraged Manning to provide more information and agreed to crack a password hash stored on U.S. Department of Defense computers connected to the Secret Internet Protocol Network (SIPRNet), a United States government network used for classified documents and communications. Assange is also charged with conspiracy to commit computer intrusion for agreeing to crack that password hash.” The problem here is that it appears that the U.S. government has no evidence that Assange colluded with Manning to break into the U.S. system.

Manning does not deny that she broke into the system, downloaded the materials, and sent them to WikiLeaks. Once she had done this, WikiLeaks, like the other media outlets, published the materials. Manning had a very trying seven years in prison for her role in the transmission of the materials. Because of the lack of evidence against Assange, Manning was asked to testify against him before a grand jury. She refused and now is once more in prison; the U.S. authorities are using her imprisonment as a way to compel her to testify against Assange.

What Manning Sent to Assange

On January 8, 2010, WikiLeaks announced that it had “encrypted videos of U.S. bomb strikes on civilians.” The video, later released as “Collateral Murder,” showed in cold-blooded detail how on July 12, 2007, U.S. AH-64 Apache helicopters fired 30-millimeter guns at a group of Iraqis in New Baghdad; among those killed were Reuters photographer Namir Noor-Eldeen and his driver Saeed Chmagh. Reuters immediately asked for information about the killing; they were fed the official story and told that there was no video, but Reuters futilely persisted.

In 2009, Washington Post reporter David Finkel published The Good Soldiers, based on his time embedded with the 2-16 battalion of the U.S. military. Finkel was with the U.S. soldiers in the Al-Amin neighborhood when they heard the Apache helicopters firing. For his book, Finkel had watched the tape (this is evident from pages 96 to 104); he defends the U.S. military, saying that “the Apache crew had followed the rules of engagement” and that “everyone had acted appropriately.” The soldiers, he wrote, were “good soldiers, and the time had come for dinner.” Finkel had made it clear that a video existed, even though the U.S. government denied its existence to Reuters.

The video is horrifying. It shows the callousness of the pilots. The people on the ground were not shooting at anyone. The pilots fire indiscriminately. “Look at those dead bastards,” one of them says, while another says, “Nice,” after they fire at the civilians. A van pulls up at the carnage, and a person gets out to help the injured—including Saeed Chmagh. The pilots request permission to fire at the van, get permission rapidly, and shoot at the van. Army Specialist Ethan McCord—part of the 2-16 battalion that had Finkel embedded with them—surveyed the scene from the ground minutes later. In 2010, McCord told Wired’s Kim Zetter what he saw: “I have never seen anybody being shot by a 30-millimeter round before. It didn’t seem real, in the sense that it didn’t look like human beings. They were destroyed.”

In the van, McCord and other soldiers found badly injured Sajad Mutashar (age 10) and Doaha Mutashar (age five); their father, Saleh—who had tried to rescue Saeed Chmagh—was dead on the ground. In the video, the pilot saw that there were children in the van; “Well, it’s their fault for bringing their kids into a battle,” he says callously.

Robert Gibbs, the press secretary for President Barack Obama, said in April 2010 that the events on the video were “extremely tragic.” But the cat was out of the bag. This video showed the world the actual character of the U.S. war on Iraq, which the United Nations Secretary-General Kofi Annan had called “illegal.” The release of the video by Assange and WikiLeaks embarrassed the United States government. All its claims of humanitarian warfare had no credibility.

The campaign to destroy Assange begins at that point. The United States government has made it clear that it wants to try Assange for everything up to treason. People who reveal the dark side of U.S. power, such as Assange and Edward Snowden, are given no quarter. There is a long list of people—such as Manning, Jeffrey Sterling, James Hitselberger, John Kiriakou, and Reality Winner—who, if they lived in countries being targeted by the United States, would be called dissidents. Manning is a hero for exposing war crimes; Assange, who merely assisted her, is being persecuted in plain daylight.

On January 28, 2007, a few months before he was killed by the U.S. military, Namir Noor-Eldeen took a photograph in Baghdad of a young boy with a soccer ball under his arm steps around a pool of blood. Beside the bright red blood lie a few rumpled schoolbooks. It was Noor-Eldeen’s humane eye that went for that photograph, with the boy walking around the danger as if it were nothing more than garbage on the sidewalk. This is what the U.S. “illegal” war had done to his country.

All these years later, that war remains alive and well in a courtroom in London; there Julian Assange—who revealed the truth of the killing—will struggle against being one more casualty of the U.S. war on Iraq.

(Vijay Prashad is an Indian historian, editor and journalist. He is a writing fellow and chief correspondent at Globetrotter, a project of the Independent Media Institute. This article courtesy: Globetrotter.)

❈ ❈ ❈

The Assange Case: The People have the Power

John Rees

The most important press freedom case of the 21st Century is about to resume in London’s Old Bailey this coming Monday.

After years of background noise swirling around the founder of WikiLeaks, Julian Assange, it is sometimes hard to focus on exactly how blindingly simple the issue at the heart of this hearing remains.

It is this: should the Trump administration be able extradite Julian Assange to the US and put him on trial under the 1917 Espionage Act for revealing material about the Afghan and Iraq wars, Guantanamo Bay prison, and diplomatic communications between states?

The Trump government’s justification for this unprecedented use of the Espionage Act is that in the words of Secretary of State and former boss of the CIA, Mike Pompeo, WikiLeaks acted as a ‘non-state hostile intelligence service’.

This designation has huge consequences. It allows the US to extend the territorial reach of its punitive legislation while simultaneous refusing its targets the right to free speech under the provisions of the First Amendment to the US Constitution.

But a moment’s thought reveals that Pompeo’s categorisation of WikiLeaks as a ‘non state intelligence service’ is either a nonsense or an unintended compliment.

The whole point of espionage is that it is carried out by one state against others. It is intended to find out secrets, keep them secret except to the state doing the spying, and thereby give that state a political, economic, or military advantage over its rivals.

What (some) journalism does is to openly publish material that the state (or others) would prefer to keep secret so that it can be known and evaluated by an informed public debate. This journalism acts on behalf of the public, not a rival state. And it does so openly, not in secret.

Pompeo’s use of the words ‘non-state’ admits half this case and, in doing so, undermines the other half of the case. A non-state actor intent on publication cannot be spying in any normal sense of the word.

Using a century-old espionage act in such circumstances is simply an attempt to criminalise journalism.

And this is indeed, in the minds of the Trump administration, the real crime that WikiLeaks has committed. It has placed information in the public domain. This is what angers them, this is what drives their multi-million-pound pursuit of Assange.

But for this persecution to reach its zenith Assange has first to be extradited to the US and put on trial in the Eastern District Court of Virginia where the state has never lost an espionage case, not least because jurors are chosen from a population of whom 80 percent work at the nearby CIA and NSA headquarters or the Pentagon.

The British Tory government has been all too willing to expedite the US extradition request. Former Home Secretary Savid Javid signed off on it, as he was required to do, without a moment’s hesitation. His viciously right-wing successor, Priti Patel, could be a Trump family adoptee.

But beyond the global politics at stake, Assange’s treatment by the justice system betrays a political class that is happy for him to disappear into the deepest of black holes.

Leaving aside the fact that he should not be in prison while he awaits his hearing, let alone in Belmarsh high security prison, his access to his lawyers has been restricted to the point which makes a full and fair trial impossible. One moment in the opening week of the hearing in February provided a stark demonstration of this situation.

Assange’s legal team requested that he be brought out of the glass cubicle at the rear of the court room so that he could sit with his lawyers and communicate effectively with them. The judge prevaricated. Then the prosecution’s QC intervened to remind the judge that this was a decision well within her powers to take and that the prosecution had no issue with Assange sitting with his defence team as this was normal practice. The judge still refused on the basis that she had to consult with the private security company that guards the court.

Assange was never allowed to sit with his legal team. He remained incarcerated at the back of the court, as much a participant in his own trial as, he said, ‘a spectator at Wimbledon’.

It is hard to overestimate what is at stake in this case. There is of course plenty of bad journalism out there. Plenty of churnalism that simply regurgitates government and corporate press releases and gossip from the Westminster bubble blowers. But for those journalists actually trying to reveal information that the rich and powerful would like to keep hidden, indeed for any whistle-blower that wants to reveal dangers to the public, Assange’s extradition would be a devastating blow.

And if it’s a devastating blow to journalists and whistle-blowers it’s a devastating blow to us all. To give only the most recent example: how much less would we have known about the true numbers of deaths in the Covid crisis, the disaster in our care homes, the standing disgrace of Do Not Resuscitate notices issued to the vulnerable, or the failure of track and trace, let alone Dominic Cumming’s tour of Britain, if whistle-blowers and journalists had not told us the facts that the government wanted hidden.

The years spent claiming asylum against extradition to the US in the London embassy of Ecuador, the year spent awaiting this hearing in Belmarsh, make it seem as if the Assange case must be reaching its conclusion. But it is not. In many ways it is just beginning.

It is a peculiarity of the British legal system that extradition cases are first heard in Magistrates Courts. These are no jury lesser courts more familiar with motoring offences than freedom of speech cases with global political ramifications.

The judge in the Assange case is clearly terrified of making any, even procedural, decision that could later be criticised. She knows that any decision, whether to extradite Assange or not, will be appealed to a higher court by the losing side.

So this titantic struggle will not be over until this hearing is over and a subsequent appeal is heard.

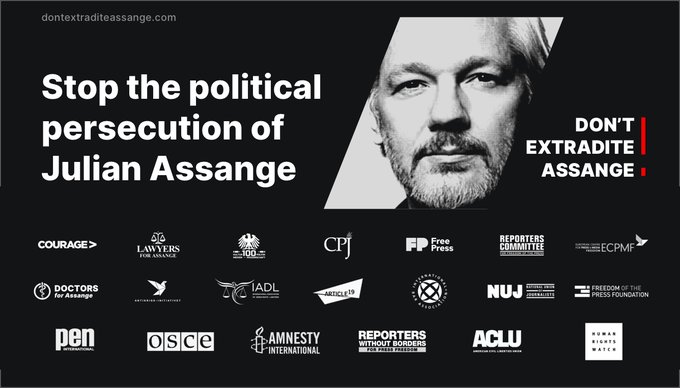

The tide has begun to turn over the Assange case. A once supportive paper turned hostile, the Guardian, is now supportive again, running editorials opposing extradition. So is the Telegraph, and even the Daily Mail and the Sun run neutral reports. Every major NGO, from Amnesty to Human Rights Watch and Pen, are opposed to extradition. But opinion needs to be turned into power. For that to happen all those who wish to see the punitive power of the American Leviathan contained, all those that want to see freedom of speech and freedom of the press preserved have a single, urgent task. That is to create a wave of public mobilisation that can force the Tory government to exercise a power that it does in fact possess: to refuse the extradition of Julian Assange to the US.

(John Rees is a co-founder of the Stop the War Coalition and a visiting research fellow at Goldsmiths, University of London. Article courtesy: https://tribunemag.co.uk.)