Right to Information users, like dissenters and democratic activists in India’s troubled democracy, have been under siege.

As the right to information (RTI) Act completes 16 years it becomes increasingly clear that democracy, and the right to information are inextricably linked to one another. An anniversary provides opportunity for review, and despite all the effort to weaken and dilute the law, it is clear that the RTI is much more than a law. It is a people’s movement.

You can circumvent, violate, and even amend a law – but you cannot amend a movement.

October 12 is 10 days after Gandhi’s birth anniversary. In the 150 years after his birth, and 75 years after Independence, the legacy of Gandhi’s ‘satyagraha’ and B.R. Ambedkar and the national movement’s constitution are being explored and strengthened in many ways by the RTI.

A decade should be long enough for a landmark legislation to have built and stabilised its domain – and for a hostile system to have got used to it; but 16 years on, RTI remains a very contested space. Interestingly the contestations are very much between the ‘haves’ and the ‘have nots’ of the information, and the subject to which it pertains.

The RTI is said to be “a tool to control corruption and the arbitrary use of power”. It is, in fact, much more than a ‘tool’ and much deeper than a policy or law. The arbitrary use of power can only suppress people for short periods of time, and their need for freedom of expression is as natural as their physical requirements of food and fresh air.

Like democratic expression, “the right to know” is part of a deep human aspiration for establishing ‘truth’, and to live with dignity, equality and justice. Despots and dictators might use innumerable means to keep their subjects passive and compliant, but they have eventually never been able to control every voice.

RTI has been brilliant, because it has allowed every common citizen using RTI to realise that they can be Hans Christian Anderson’s little child recognising the emperor for what he was (not) wearing. They can therefore and they can use the Constitution and the path of ‘Satyagraha’ to fight their battles for justice.

“The emperors new clothes” and “Satyagraha” are not just allegories that help explain the logic of the RTI in India. The opposition to RTI comes from an insidious criticism about who uses the RTI for what. One of the allegations loosely made about RTI users is that they are ‘mostly blackmailers’. While it is true that some blackmailers have found the RTI to be a means by which they can effectively conduct their practice, it is, in fact, a battle between two thieves. Handled effectively, it could lead to an exposé of both.

Like all movements, the RTI cannot speak for each individual, but there can be little doubt that the RTI is a non-violent method of trying to establish the truth, and using the truth to fight injustice. More importantly, however, it can be controlled through proactive disclosure in the RTI Act itself.

The demand for the RTI began with an agitation of workers and peasants for wage entitlement and the right to see their muster rolls (work records) in central Rajasthan in the early 1990s. In the process, the scope of information access was defined in its broadest terms and transparency and accountability began to manifest themselves as clear and understandable concepts in the Indian polity.

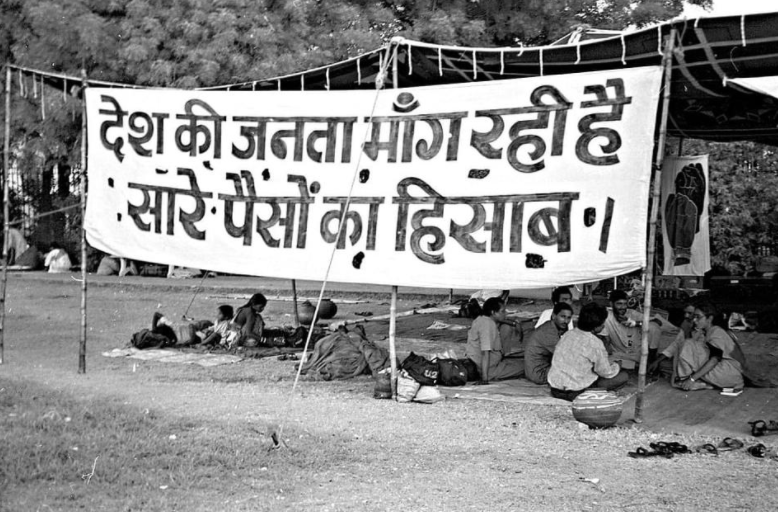

The two slogans of the movement born at that time defined the Indian RTI movement from its inception – “Hamara Paisa, Hamara Hisaab” (our money, our accounts), and “Hum Janenge, Hum Jiyenge” (the right to know, the right to live) . The struggle and campaign grew to be a robust peoples’ movement fundamentally influencing the passage of the national RTI law in 2005.

On October 10, ordinary citizens and users of the RTI from the area where the movement began 30 years ago, met in the School for Democracy, for a discussion and analysis on the use of the law. Their use of the law, demonstrated how the citizen has managed to penetrate the intricacies of governance, probing legalities, and establishing realities. The understanding of the RTI law is pervasive – more people know about, and use this law, than perhaps any other.

For this reason the RTI law and its users have upheld Article 19, 14 and 21 as the right to question and demand answers, mandating the ordinary citizen to exercise her equality, survival and sovereignty. A most important if elusive value enshrined in the constitution has been strengthened through the use of the constitutional right that has sustained it.

But it is not just the freedom of expression that the RTI Act has a synergetic relationship with.

Justices Shah, Sen, and Muralidharan recognised the wide and deep relationship of the Right to Information with the fundamental rights in their Delhi high court judgment. The order said that the peasants and workers of Rajasthan had through their struggle for the Right to Information, raised fundamental questions of equality, social justice, and the right to life, and therefore, along with freedom of expression under Article 19 of the Indian constitution, the RTI should be seen as a manifestation of the right to life under Article 21, and the right to equality under Article 14.

Many RTI applications and struggles have brought much larger questions of law and justice into the domains of democratic discussion, exploring even constitutional principles and concepts through the practice of democracy.

However, today the RTI as a law is being undermined, as is the constitution of India. To understand the nature of the battle, one has to understand the values behind a social democracy, and recognise the connections RTI has with these fundamental values of humanity. It is those values that have made the RTI an irrepressible movement of the people.

The RTI will overcome arbitrary power, because the peoples’ quest for fact, truth, justice and even equality, is insatiable.

Fundamental rights cannot be forever curtailed by any regime. The RTI has done much more than lifted the lid of a Pandora’s box of misdeeds – it has more importantly opened a floodgate of citizen activism. It has given vital spurts of oxygen to democratic citizenship. It has helped transform every battle for truth and justice.

People will struggle until they get their equal share, and collectively celebrate every small and big success. It is that “heaven of freedom” that will sustain even the most oppressed and marginalised people through their darkest moments.

(Nikhil Dey and Aruna Roy are Mazdoor Kisan Shakti Sangathan and RTI activists. Article courtesy: The Wire.)