Neera Chandhoke

In the 18th and 19th centuries, colonial powers justified the conquest of large parts of Asia and Sub-Saharan African in terms of an almost divine mission. The mission compelled them to bring “development” and “civilisation” to the territories that had been colonised. The justification was, but a cloak, for more nefarious purposes. The colonised lost control of their land, resources, and labour. These were yoked to the project of garnering economic profits for the imperial power.

Colonies were treated as a piece of real estate that could be plundered at will. The claim that colonialism would bring development to the inhabitants—childlike at best, savages at worst, but certainly heathens who were inept, inefficient and ineffective—was deeply offensive. It generated a backlash in the form of a struggle for freedom. The leaders of the freedom struggle had to re-establish political control over their own land. They also had to reclaim their identity as people who mattered. They had to establish that they were capable of ruling their own country.

Seventy-two years after Indians wrested their freedom from the British, the central government has imposed what can be termed “internal colonialism” in Jammu and Kashmir (J&K). The script of establishing control over the state coheres closely to the colonial project. Consider that the terminology of bringing “development” to the people of J&K has been summoned as a legitimising device. The economist Jean Drèze has established that indices of social development in the state are higher than in many other states, including Gujarat. But this does not seem to matter to the ruling class. The people of the state have been stripped of their dignity by the downgrading of, and the bifurcation of, their state into two Union Territories in a completely arbitrary fashion.

Recollect that the frontiers of countries in Sub-Saharan Africa had been drawn by imperial power. Armed with a pencil they drew lines on a map of the continent at a meeting in Berlin in 1885. They called these lines boundaries of states. Much like the colonised were deprived of basic rights, the people of J&K have been divested of their constitutional rights. This, they are told, is for their own good.

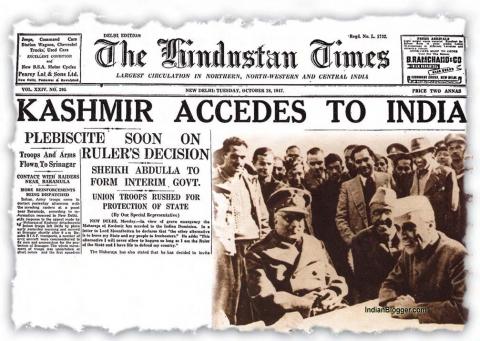

What is more worrying is the reaction of other Indians to the internal colonisation of J&K. Except for a few notable exceptions, our fellow citizens have celebrated the erosion of the status of the state. No one seems to want to understand that the relationship of J&K to the central government is complex. No one recollects that the former princely state had acceded to India in October 1947 on certain terms and conditions, and that these were codified in Article 370 of the Constitution. No one bothers to remember that the people of the state had been promised a plebiscite and that this did not take place. And everyone prefers to forget that successive governments in Delhi have seriously violated democratic norms in J&K, whether these pertained to elections or to civil liberties.

Over the last five and a half years we seem to have mislaid our capacity for informed and reasoned debate. We see surges of emotions that hail every decision of the leadership. We live amidst the politics of din, the terminology of abuse and vicious trolling. We witness with great dismay the waylaying of democratic norms, and of the right of citizens to hold the government accountable. We seem to have lost our ability to stand up for fellow citizens whose rights have been infringed. It is time to raise a question that is central to our democratic life and federalism. Why not Article 370? Why not regional autonomy for groups that wish to protect and preserve their distinctive culture and language? Why do we fail to realise that a diverse society needs different policies for different groups within the country? Why have we forgotten the arguments that stress the importance of federalism?

The defence of federalism is located in at least three sets of arguments. One, in large societies, decentralisation of power enables citizens to access state and local governments, and hold elected leaders responsible. Two, decentralisation is indispensable for administrative and financial efficiency. Three, decentralisation allows elected representatives to gauge the needs of people in far-flung areas and design appropriate policies. For these and other reasons, federalism has been seen as appropriate for large and complex societies.

The debate on federalism acquired new urgency with the end of the Cold War that followed the collapse of actually existing socialism and the outburst of conflicts and civil war over identities. Groups struggle for resources, but these struggles can be resolved given some imagination, a great deal of generosity and some capacity for negotiation. Identity conflicts have proved infinitely more difficult to resolve; they are simply intractable. Some groups demand a share in the resources of the country, others demand regional autonomy and still others wish to secede. Civil wars have led to thousands of deaths, massive displacements and suffering. “Each new morn” says Macduff of war in Shakespeare’s Macbeth, “New widows howl, new orphans cry, new sorrows strike heaven on the face, that it resounds”.

With the explosion of identity wars in the aftermath of the fall of the Berlin Wall, a fourth argument was added to the defence of federalism. Federal arrangements might help to contain combustible politics of identity. The acceptance of identity politics did not come easily to democratic theorists. Many scholars were uncomfortable with linguistic, religious and ethnic identities. They followed John Stuart Mill who in 1861 wrote on the issue in his famous work Considerations on Representative Government. Free institutions, he wrote, are practically impossible in a country made up of different nationalities. People speaking different languages cannot develop fellow feeling. Nor can they generate a united public opinion that is necessary for the working of representative government.

In the opening years of the 1990s, the upsurge of hyper-nationalist identity politics, conflict and war forced democratic theorists to recognise the importance of, and the power of, identity. People are willing to kill and die for their religion, their language and their ethnic identity. This led to the break-up of countries, for example, Yugoslavia and Czechoslovakia, and secession in other countries. It has been calculated that the increase in the membership of the United Nations from the original 52 members in 1945 to 149 in 1984 was due to decolonisation. The growth thereafter from 151 in 1990 to 193 at present is largely the result of secession.

Democratic theorists had to, in effect, address a new political predicament—how can identity wars that have proved inflexible and resistant to mediation be contained? Though the literature on federalism as the preferred solution to identity struggles is divided, on balance, federalism, regional autonomy and the creation of federal units on the basis of linguistic, ethnic and religious identities is considered a better option than unitary government. Elites temper their demands and their intransigence the moment they are granted a state of their own. From resisters they become stakeholders. And anxieties about religious and linguistic identities are assuaged.

Much before the western world confronted the issue, India had understood the significance of protecting and safeguarding languages and the culture it embodies. Jawaharlal Nehru acknowledged this in April 1963. Intervening in the debate on the Official Languages Bill in the Lok Sabha, he remarked that in matters of language one has to be very careful. We have to be as liberal as possible and not try to suppress a language. “Whenever an attempt has been made to suppress a popular language or coerce the people into using some other language, there has been trouble.” Nehru spoke from experience: a rampant conflict over the national language and the demand for linguistic states, both of which came up in the first decade of the 20th century.

In the mid-1960s, a movement appeared on the political scene that held that Hindi should be the national language. The Hindi movement, which quickly acquired communal overtones because it positioned itself against Urdu, was hotly contested by Tamil nationalists. Repeated anti-Hindi agitations by the Dravidian leadership right until 1965 resisted what was called Brahmanical domination. Tamil nationalists threatened to secede.

Dr B.R. Ambedkar had remarked that no provision in the Constitution bred as much anger as that of the national language in the Constituent Assembly. The Assembly, therefore, postponed the adoption of Hindi as the national language to 1965. As the date drew near, Madras city was shaken by agitations; portions of the Constitution that dealt with the language issue, books written in Hindi and government documents were burnt on the streets. The central government decided that it was safer to compromise. The Official Amendment Act of 1967 adopted the three-language formulae. Major languages have been included in the Eighth Schedule.

Today we cannot imagine the anger and the passion that was expended on the issue of the national language. What is significant is that the government of the day accepted that language was important for people. Which language we speak determines what opportunities we have access to. Language is also important for us because language is culture, it shapes our worldview. To take away language is to diminish human beings.

The second issue that rocked the country was the conflict around linguistic states. The demand had erupted after Bengal was divided in 1905. The Indian National Congress agreed that after India became an independent country, states would be reorganised on the basis of linguistic identities. But when the time came, the Congress government hesitated and prevaricated. After the shock of Partition, which was legitimised by the two-nation theory, the new government could not reconcile with the linguistic reorganisation of states. It might have balkanised the country further.

However, the issue could not be swept away from the centre stage of politics. History has shown us that identity politics acquire a dangerous trajectory; they become independent of economic sops such as “development”, “integration” into the country, or more “opportunities”. In October 1952, Potti Sriramulu, a respected freedom fighter, went on a fast-unto-death for a separate state for Telugu-speaking people. By December of that year discontent erupted in the Andhra region. Sriramulu’s health deteriorated, and he died on 15 December 1952. Telugu speaking areas were wracked by riots. On 19 December, Nehru was forced to concede the new state of Andhra Pradesh. The state was carved out of Madras state, excluding Madras city. Telangana was incorporated into Andhra Pradesh.

The decision propelled other movements for linguistic states and Nehru appointed a States Reorganisation Committee on 22 December 1953. The Commission received and considered over 150,000 documents for and against linguistic states. The first round of state formation during 1956-1966 was based on language. Subsequent rounds, the formation of states in the Northeast, and the creation of Uttarakhand, Chattisgarh and Jharkand were justified on other grounds such as economic backwardness. In 2014, Telangana was constituted as a separate state again on the basis of language and shared cultural traditions.

India’s political experiment added another bow to the argument for federalism, the need to accommodate identity issues. That experiment has worked well, defusing tensions and allaying fears. The recognition of identity is in keeping with the best tradition of contemporary political theory, that there is no such thing as an abstract individual. Individuals are social beings. They realise their sociable nature through membership of associations in civil society, ranging from bird watching clubs, to book reading groups, to literary societies, to theatre-going associations, to cricket clubs, to civil liberties unions that keep watch on acts of omission and commission of the government to even film fan clubs. Yet, undeniably, we are intimately attached to the community we are born into. Our community teaches us a language that allows us to make sense of the world, of our own place in the world, and our relationships with others. It follows that an individual should be assured secure access to her community. This is an essential precondition for being human.

The case of Jammu and Kashmir was different. It came into existence in 1846. When the Maharaja of Kashmir acceded to India in October 1947, he insisted on regional autonomy. For Jawaharlal Nehru the inclusion of J&K in India was important. It validated the doctrine of pluralism and secularism, notably that the country has place for all religious groups and that they will be treated equally by the state. If the inhabitants of a state form a minority and for that reason are vulnerable to majoritarianism, if they fear that their religion, their culture and their language is threatened, they should be accorded special protection in the form of regional autonomy. This commitment was incorporated in the Constitution in the form of Article 370. Nehru knew that the people of J&K could only be a part of India if they were assured of their identity and if the state protected their distinctive culture. This reasoning has also been applied to parts of the Northeast that possess a well-defined culture and language.

It is regrettable that over the years successive governments in Delhi have violated the basic terms of the contract with J&K. Yet the people of the state were willing to give democracy a chance. Discontent with the systemic violations of Article 370 and of all democratic norms burst into flames in 1990. Since then the people of the state have lived with violence that is unleashed on them from all sides. The Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) government has tried to contain this violence militarily. But political wars cannot be fought militarily. There is no evidence that violence has abated under the iron hand of the central government. Though all forms of violence are condemnable, state violence that terrorises the citizens of the country is sickening. It contravenes democracy, it leads to trauma.

The very people we voted for, the very people we entrusted our country to, have betrayed us. What could be more traumatic? The poet Umair Bhat gives us an indication of this trauma in his poem The Siege:

In the streets, filled

with impenetrable smoke,

Kashmir is burning again,

so are tyres, rubber

and logs. The houses

are burning. Fire

runs in waves. The air,

heavy with soot, murmurs

death overhead….

Each evening

on the dinner tables

we prepare for our little wars

we will fight in the morning.

This is but a part of the story of violence that runs rampant in Kashmir. Thousands have been killed, thousands have been detained, thousands have disappeared, young children have been radicalised and several thousand have been tortured. The people of Kashmir are caught between the Charybdis of Indian security forces and the Scylla of armed groups that have been active in the Valley since the late 1980s. Terrible forms of violence have engulfed minds and crippled imaginations, forbidden people to think of the future, compelled them to concentrate only on holding minds and bodies together. Violence has painted the history and the present of Kashmir in blood and has blurred the future by the smoke that curls upwards from burning homes and villages. Violence has begotten only violence and led to multiple tragedies of epic proportions.

The tale of the Kashmir tragedy could have been foretold. The Government of India, desperate to prevent further Balkanisation of the country, embroiled in a war that was not of its own making with Pakistan in 1947–48, pilloried in the United Nations by major western powers that had turned against India, and pressurised by right wing forces to integrate Kashmir into the country, was to later adopt extremely short-sighted policies in the Kashmir case. In retrospect it is surprising that the government did not realise that it was not dealing with a population that had been rendered acquiescent under princely rule.

The Government of India was dealing with a people who had mobilised against the misrule of the monarch since the 1930s. This politically aware population witnessed a series of cataclysmic events in the aftermath of 1947, the terror and the atrocities inflicted by raiders from Pakistan in 1947, the disruption that followed the war between India and Pakistan on Kashmiri soil, and the partition of the community and of the homeland between two, and then three countries. Above all, this population bore witness to the breach of contractual and constitutional obligations by the Government of India. Yet the Kashmiri people were prepared to give democracy a chance. But it was precisely democracy that was compromised and denied to them.

Seventy-two years after J&K acceded to India, the Government of India has erased the state from the map of India. We do not know what the consequences will be because the people are shut off not only from the world, but also from their own kith and kin. A sense of foreboding, however, permeates the atmosphere. When Maharaja Hari Singh acceded to India in 1947, the country was poised to be a democracy. The status of the former princely state was fixed by making it a part of the federal structure and granting it regional autonomy so that the distinctive culture and identity of the people could be protected against marauders.

The hope that the Indian state could deliver to the people of the state protection, democracy and justice frittered away by the end of the 1980s. Thereafter the Valley has seen little but discontent and the politicisation of the people. Upon a deeply politicised people the Indian government has imposed humiliation. This is worrying. Thomas Hobbes wrote, “Though nothing can be immortal, which mortals make; yet, if men had the use of reason they pretend to, their Common-wealths might be secured, at least, from perishing by internal diseases.” But reason is not a constitutive aspect of the Kashmir policy of the Government of India. Can the Commonwealth be properly secured? Can rulers throw internal colonialism into the dustbin of history?

(Neera Chandhoke is a former Professor of Political Science in Delhi University.)