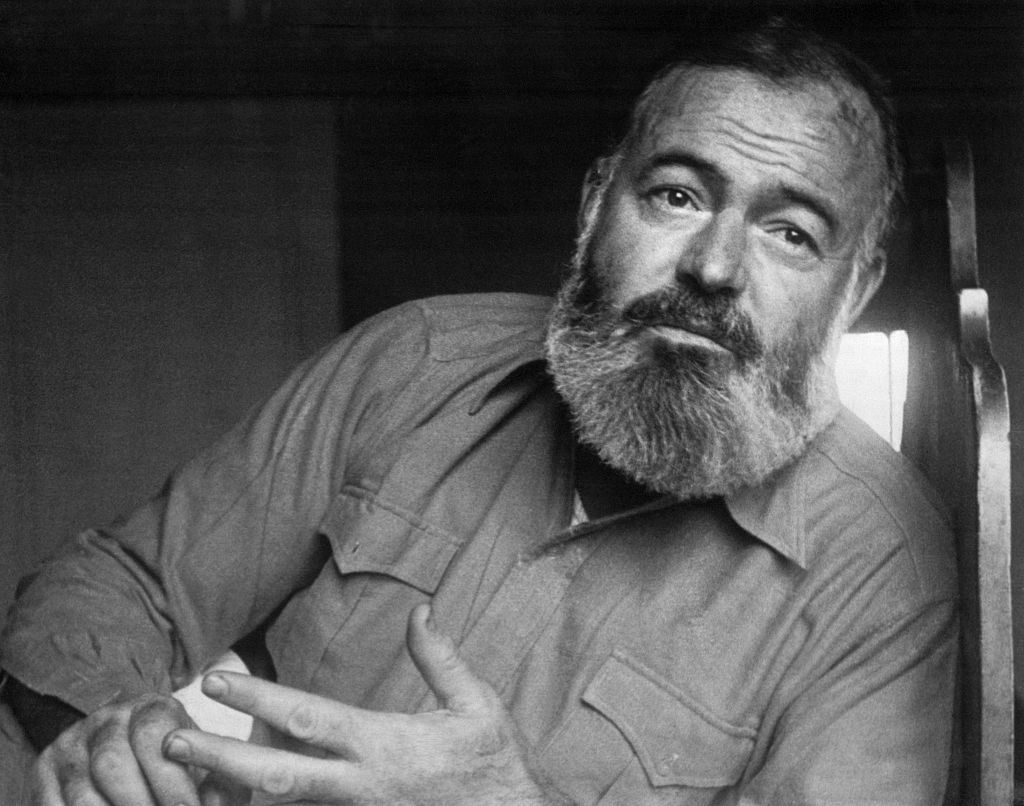

[Ken Burns, the maestro of documentary television, is back with Hemingway, a new three-part, six-hour series for PBS, codirected with longtime collaborator Lynn Novick. Their biopic chronicles Pulitzer Prize winner Ernest Hemingway’s life, work, loves, travels, and causes with archival footage and original interviews with Peruvian novelist Mario Vargas Llosa, as well as the author’s son Patrick Hemingway and, surprisingly, Senator John McCain, among others.

Burns has won four Emmys and been nominated for nine more, as well as for two Oscars, for documentaries including Huey Long (1985), The Civil War (1990), Baseball (1994), and The Dust Bowl (2012). Often working with producer/director Novick, these films have been imbued with social awareness and stamped by cinematic storytelling techniques.

Burns and Novick bring their talents to Hemingway, with cinematic vignettes detailing “Papa’s” famed globe-trotting exploits across Paris, Spain, Key West, Cuba, and Africa. But Hemingway also focuses on the writer’s active participation among the political left, using his renown and literary gifts as a novelist and journalist to try to “write” the wrongs of the Depression and fascism.

Jacobin contributor Ed Rampell recently spoke with Burns about Hemingway’s encounters with war, the FBI, Cuba, and how Hemingway may have been the Bay of Pigs’ most famous casualty.]

ER: Perhaps the peak of Hemingway’s celebrity in the 1930s was also when he first began to delve into politics. What was his reputation among the American left at that time?

KB: There was the presumption that, at the time, in the middle of a great depression, his stories were devoid of, let’s just say, a dialectic that was very much front and center for the American left: confronting the tragedy and pain of the Depression and the underlying causes of it. So he was dismissed, and he reacted, saying, “There’s no Left and Right in literature. There’s only good writing.”

He himself seemed to be aligned in a more conservative fashion, less government. The only thing that is certain, he said, is “death and taxes.” He really despised the Roosevelt administration’s attempt [at] the Florida Keys, where he lived. When the hurricane hit, and jobless veterans who had been there, many hundreds of them lost their lives, he blamed the Roosevelt administration and wrote an article for New Masses saying that.

And so, then, almost instantaneously, you have this transition on the part of Hemingway, in which he ends up writing To Have and Have Not (1937), his bad attempt at a proletarian novel. Then him going off to follow the Spanish Civil War with definite loyalty to the leftist Loyalist government that was in the process of being overthrown by the fascist Francisco Franco and his allies, Adolf Hitler and Benito Mussolini.

Hemingway then made a few pacts with the devil in the fact that Joseph Stalin, who’d made himself the sort of protector of the Loyalists, had so infiltrated the cause that he was weeding out anybody who wasn’t a Stalinist. And it was something Hemingway didn’t write about in his journalism, though, strangely, it made it into his fiction. In his journalism, he looked the other way. This caused a severe rupture with novelist John Dos Passos, who thought it was so opportunistic.

It’s a very complicated pirouette within his own self. That’s what’s so endlessly fascinating about Hemingway, is that in the Whitmanesque sense, he contained multitudes.

ER: What did Hemingway do while he was in Spain? Who did he write for there?

KB: He had a very lucrative contract to give dispatches and then larger articles [for the North American Newspaper Alliance newspaper syndicate], and he was paid more than anybody else. He was writing with Martha Gellhorn, turning out dispatches — very poetic, very beautiful.

It’s interesting — his archenemy at the time, Franklin Roosevelt, invites him (through the intercession of Eleanor Roosevelt, a friend of Martha Gellhorn) into the White House to screen The Spanish Earth, by the communist filmmaker Joris Ivens, in which Hemingway is the writer and the narrator. The First Lady hosted a screening to impress the president — in his own way, he understands the much more complicated dynamics of having to remain neutral in relationship to what’s going on in Spain.

So, Hemingway’s got kind of bewildering gyrations in different political polarities.

ER: In your film, Senator John McCain says that the Loyalist-aligned hero of ‘For Whom the Bell Tolls’, Robert Jordan, was his role model. But it seems to me that McCain drew a curious conclusion from the novel, spending his life either fighting or promoting imperialist wars of aggression.

KB: This is where the superficiality of small-p politics is involved. This is a literary character that Barack Obama, who ran against John McCain for president, also cited as an important influence, which I find so interesting.

As McCain says in the film, he — McCain — is a flawed man, serving a flawed cause, meaning the cause that Robert Jordan served, meaning that he often was involved in things and doing it with a certain kind of existential nobility. A lot of people who are captured, if you will, by a literary figure — obviously a made-up literary figure, but based in some reality — there’s an emotional connection. I can’t speak to the dialectic of the fraudulence of John McCain in regard to that, if it is [fraudulent]. He genuinely loved Robert Jordan.

[Novick and I] did a film on the Vietnam War, and we interviewed a woman named Le Minh Khue, who, as a young girl, volunteered to go down the Ho Chi Minh Trail and repair the damage done by American bombers — incredibly dangerous work. And she carried with her For Whom the Bell Tolls, and she thinks one of the reasons she survived is that Hemingway taught her how to think outside and survive in the war.

ER: Your documentary chronicles the fact that Hemingway was among those talents who fell under the cloud of suspicion during the McCarthy era. What contact did Hemingway actually have with Soviet officials in Spain and then, later, in China during his honeymoon with Gellhorn?

KB: In Spain, he turned a blind eye to some of the ruthless acts of Soviet commissars there, [who were] often disappearing people, executing them without trial, torturing people. He knew this was going on. He dined with them.

In China, Hemingway was ostensibly on this trip observing [the China-Japan War] on behalf of the US government. But because, I presume, of the contacts he’d made in Spain, on the eve of World War II, Moscow was also apparently asking for material, and he’d promised to send observations to them but never did. It’s a headshaker.

ER: Did Hemingway’s leftist convictions mark him for ridicule by other members of the literati? I believe Edmund Wilson took shots at his politics.

KB: At the time, his outsize personality outweighed the tiny, internecine things. He was basically beloved within the mainly left-wing literary scene after he began to “turn” with that first article in New Masses — then with To Have and Have Not and, obviously, his reporting on the Spanish Civil War. Everybody wanted to claim him — and he wished not to be claimed.

ER: How did McCarthyist America handle the fact that its beloved national author was so pro-Left?

KB: I’m not sure that they understood it. Remember, there’s not mass readership to New Masses when he writes his anti-Roosevelt thing about the hurricane and the death of the people that he’d helped fish out (some of them were drinking buddies at Sloppy Joe’s in Key West). The dominant image of Hemingway is more the macho image. So I don’t think, in any way, there’s a blip there.

He does change; he goes to Africa in the ’30s. It’s very paternalistic, colonialistic. He refers to the porters as “boys.” But Hemingway came back in the ’50s, twenty years later, and it was a different thing. He stopped shooting, started taking pictures — realizing, as he put it, that every person had a name.

By this time, he’s also being overtaken by madness — we don’t know where that’s from, whether it’s pure genetics or it comes from PTSD or addiction and abuse of alcohol and other drugs or a number of traumatic brain injuries.

ER: How did the FBI feel about Hemingway’s politics? Were they surveilling him?

KB: He thought they were. I don’t know. He was the most famous writer on Earth. He was living in Cuba. I’ve got to assume he sympathized with Fidel Castro’s revolution. He knew how corrupt Fulgencio Batista’s government was. He also understood, in a realpolitik kind of way, that the Ketchum [Idaho] house would be a hedge against the loss of his beloved Finca [Vigía, Hemingway’s home near Havana, now a museum]. In some way, you could argue that it was the loss of that that really sent him completely around the bend. He has fantasies of the FBI checking him out. Who knows what the origin of that is?

ER: Tell us about Hemingway’s longtime ties to Cuba.

KB: He started making trips there in the early 1930s. He was based in Key West, in a house that was essentially purchased by his rich wife’s uncle, who adored Hemingway. I think he felt constrained, so as he discovered the pleasures of deep sea fishing, he’d go to Bimini and sometimes travel to Cuba, and he fell in love with Cuba and eventually bought a house there. And he spent more time there than any other place that was his home — certainly longer than Key West or Paris. Maybe Oak Park [the Chicago suburb where Hemingway was born] is about the same amount of time.

ER: Where was Hemingway politically at the time of his death?

KB: How can you measure that? Somebody who was so mentally degraded? Clearly, he sympathized with the Cuban Revolution, but the Bay of Pigs ended any opportunity for him, he knew, to be able to go back to Cuba. And he was dead in six months.

ER: Hemingway has fallen out of favor in the academy. Do his leftist politics play a role here?

KB: No. Ironically, to whatever extent he’s fallen out of the academy has to do with his maleness, macho-ness, whiteness, and deadness.

(Courtesy: Jacobin, a prominent US socialist journal.)