Uttaran Das Gupta

In a poem from the 1990s, Telugu poet Varavara Rao details the night before being arrested:

Our sleepless wait

Altering the date

Was to efface

The bittersweet divides.

Even as you say, alas,

Will they take you away tomorrow?

It’s already the day

Today

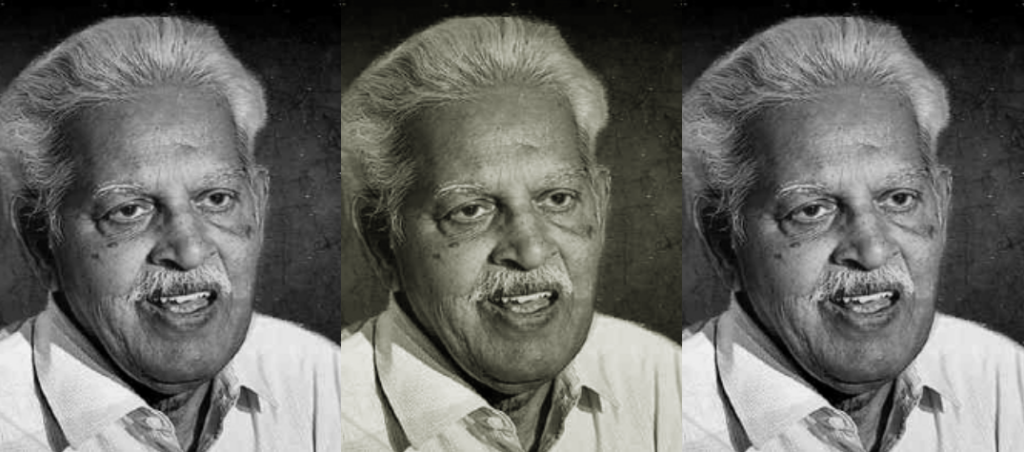

Rao, 79, has been arrested several times during his six-decade-long career as a man of letters and political activism. In a recent article, his niece, Varsha Gandikota-Nellutla claims: “It is, in fact, possible to sketch independent India’s history simply by the dates of fabricated cases brought against him by the Indian state: over the last 45 years, there have been 25, for which he has spent eight years in prison, awaiting trials that would eventually acquit him.”

He was till recently lodged in Mumbai’s Taloja jail in relation to the Elgar Parishad case, and was moved to a hospital after testing positive for COVID-19. Over the past couple of days, the clamour to get him released has increased in India and abroad. Some have even claimed that by ignoring Rao’s health, the state was imposing capital punishment on him, without even a trial.

The treatment that the Indian state has meted out to Rao – earlier and now – might seem Platonic.

In his seminal work, The Republic, ancient Greek philosopher Plato, infamously, bans the poet from his utopian city state. He uses the example of painting to establish that poets are mimetic artists, and therefore they do not speak the truth. In Book X, he gives the example of a bed – or a couch, according to differing translations. There is the idea of the perfect bed, then there is the bed that the carpenter makes, and finally the bed that the artist paints. Surely the painting is artificial – and the creator of such a painting or a work of art, that is, an artist or poet, is a creator of untruths.

While The Republic is Plato’s most commonly cited work, he takes on poets or their allies in other books as well. For instance, in Ion, Plato’s mentor Socrates challenges the rhapsode Ion to explain how he can be truthful and an artist at the same time. Rhapsodes were performers of Homeric poetry in ancient Greece. Ion confesses that when he performs, he can narrate the details of a warfare as written by Homer in his epics, but is he an army general? Socrates concludes that nether Homer nor Ion are soldiers, and therefore it is impossible for them to have such detailed knowledge of warfare. Hence, they both must be lying.

Plato’s anxiety about poetry arises possibly out of a personal experience. As he writes in Apology, at Socrates’ trial – which resulted in his conviction for being an enemy of Athens and execution by suicide –Aristophanes’ play The Cloud was presented as evidence. In his defence, as reported by Plato, Socrates claims that the eponymous character in the play, who claims to “walk the air and talk about various things” is not him at all, but a misrepresentation. But this evidence was accepted by the judges. In the anxiety-ridden climate of post-Peloponnesian War Athens, fake news like this had sufficient traction – something that’s not really unfamiliar to us now.

India seems to have turned this Platonic anxiety on its head, making the utterance of truth a difficult endeavour in this country.

In the Democracy Index 2019, published by The Economist Intelligence Unit in January this year, India slipped 10 places to rank 51 and was classified as a “flawed democracy”, with a score of 6.9. In 2018, its score was 7.23. The report said: “The primary cause of the democratic regression was an erosion of civil liberties in the country.” On the World Press Freedom Index 2020, released by the Reporters Without Borders (RSF), India is ranked 142, among 180 countries, falling two places since 2019. On the Impunity Index 2019 – published by the Community to Protect Journalists, tracking the number of unsolved murders of journalists in a country – it is ranked 13, with 17 solved killings, making it one of the most dangerous places in the world for journalists.

While Western poets have always negotiated Plato’s challenge, one of the most passionate repudiations has been from the British Romantic P.B. Shelley. For the Romantics, who imagined themselves as millennial prophets, the suggestion that poetry was mimetic was anathema. They were the lamps, not the mirrors. In his essay, A Defence of Poetry, Shelley declares that poets are “the unacknowledged legislators to the world”, the keepers of moral and social code. In his famous lyric, he describes the poet as:

…hidden

in the light of thought,

Singing hymns unbidden,

Till the world is wrought,

To sympathy with hopes and fears it heeded not.

Rao is such a legislator. If he were to die in custody without a trial, it would not be Platonic. On the contrary, it would be an insult to truth that Plato enshrined in his philosophy.

(Uttaran Das Gupta has recently published a novel, Ritual, and teaches at O P Jindal Global University, Sonipat.)