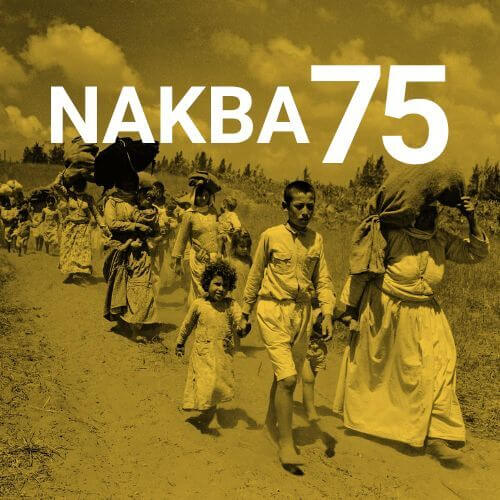

More than 75 years ago, Palestinian writers, intellectuals, historians, and political critics began to adopt a new conceptual term into the global lexicon–“al-Nakba.”

Literally meaning “the catastrophe,” the Nakba has defined and mutilated Palestinian identity. It has come to refer to a specific point in Palestinian history, but is also a currently lived reality.

It is common for annual commemorations to assume that the Nakba was a singular event, beginning and ending in the late 1940s, when Zionist forces carried out the mass ethnic cleansing of the Palestinian people from their ancestral homes. But although the Nakba is commemorated in May of every year, the only reason that month is chosen is because it serves as the mirror for the moment in history when Zionist massacres and bloodbaths became legitimized by the international community with the recognition of the Israeli state.

But those bloodbaths have never ended. The recent Israeli assault on Gaza that killed 33 people, most of them civilians and children, stands testament to the fact that the Nakba is ongoing.

But what do we really mean when we speak of an “ongoing Nakba?” It means the Nakba repeats itself every year, every day, in fact–and every new Israeli venture of colonial expansion is just another iteration of it. It has continued in the countless massacres and expulsions committed against the Palestinian people since 1948, and it continues today in places like Gaza, Masafer Yatta, Hebron, Nablus, Jenin, Bethlehem, al-Naqab, and all of Palestine from the river to the sea.

Taken together, these myriad acts of displacement map out the Nakba as a historical structure. “The ongoing Nakba” is not a metaphor, but the assertion of an existing reality. It repudiates the notion that the Nakba is a frozen moment in history, rejecting the reduction of the Palestinian experience to a tragic but discrete misfortune.

In other words, the Nakba was not an event, but a historical trajectory.

The Nakba’s meaning is erasure

Without the Nakba, Israel cannot exist. “Plan Dalet,” the Zionist master plan for the ethnic cleansing of Palestine, instrumentally utilized massacres to force the Palestinian population into flight for fear for their lives. The size and extent of these massacres continue to be unearthed through historical documentation, the collection of historical archives, and the uncovering of mass graves where Zionist militias buried the Nakba’s martyrs. Oral testimonies also reveal the heroism and bravery of the Palestinian people in resisting these massacres and fighting to the last breath.

It is in this context that Israel was established–over the ruins of historic Palestine and on top of the rubble of the 500 Palestinian villages that were destroyed by the Haganah, the Irgun, the Palmach, the Lehi-Stern Gang, and after May 1948, the Israeli army.

It was in the midst of this process in 1948 that the “Nakba” as a term was first coined–by Syrian and Arab nationalist writer and thinker Constantine Zureiq in his Ma’na al-Nakba (The Nakba’s Meaning). It was first employed in October and November of 1948 by Zureiq and peers like Dr. George Hanna to refer to what the establishment of the Israeli state meant for Palestinians—and what that meant was the erasure of Palestine and Palestinian existence.

Today, 78 kilometers northeast of occupied Jerusalem, the Givati Museum celebrates the crimes committed by Zionism during Operation Yoav, when the newly created Israeli army took over the south of Palestine between October 15 and October 22. Likewise, the massacres are explained in detail at the Herzl Museum, the Rishon LeZion Museum, the Palmach Museum, and the newly renovated Independence Hall in what is now Tel Aviv, a city built on top of at least seven Palestinian villages and towns.

In this way, the formation of the Israeli state and the attempted erasure of the Palestinian people were one and the same, two mutually constitutive processes–in other words, the Nakba is the reality that continues to run parallel to every celebration of Israel’s “independence.”

Pacifying the survivors

Palestinians in imposed exile and the diaspora constitute more than half of the entire Palestinian population–an estimated 14 million people.

This means that the Palestinians who remain inside Palestine are less than half of the Palestinian people and are spread within small spaces in the West Bank, Gaza, Jerusalem, and the few cities and towns which remain within the control of the Israeli state.

In continuing the Nakba, a primary strategy employed by Zionist militias was to borrow from the British Mandate’s divide-and-conquer approach to colonial domination. This includes dividing the Palestinian population across geography, culture, politics, language, and variations of violence.

Within the borders of what is recognized as the Israeli state–the lands occupied by Israel in 1948–only 1.7 million Palestinians remain. Thousands of those are “present-absentees”–internally displaced Palestinians with Israeli citizenship who were forced out of their villages and resettled a few kilometers away. By decree of Israeli courts, they are prevented from returning to those villages. Instead, these Palestinians are sprawled across the Galilee, the Triangle, and the south of Palestine in the Naqab, and face harsh policing, organized crime encouraged by the Israeli authorities, discriminatory policies, and the suppression of the expression of their identity, language, and Palestinian culture.

Almost a third of the West Bank population, close to one million people, are Palestinian refugees, and they continue to face military incursions and intermittent small-scale massacres.

In Gaza, more than 70% of the population, or almost 1.6 million people, are also refugees. The recent Israeli assault on Gaza killed 33 people, most of them civilians and children.

All of this stands testament to the fact that the Nakba is ongoing. Wherever they are, Palestinians are subjected to these processes of erasure, evidence of the fact that the negation of Palestinian existence itself is the end goal of Zionism.

Resisting the Nakba

When my own grandfather recalls the events of the 40s, he always returns to the moment he gathered his father’s limbs. My grandfather was turning 18 that day, and instead of pursuing medical school, he became a resistance fighter.

This encapsulates the dynamic of resistance that the Nakba has generated. The Nakba’s pains pushed Palestinians towards confrontation at a time when other Arab states were undergoing decolonization.

Like my grandfather, today’s generations have not lost the impetus to turn grief into rage. During my coverage of the revival of armed resistance in the West Bank over the past two years, the youth I encountered echoed this grief.

“Almost fifteen years ago, he was killed in front of me.” Abu Bashir, 30, a fighter with the Lions’ Den armed resistance group, told Mondoweiss last October. His friend was shot from an Israeli military tank stationed near their home during the days of the Second Intifada in Nablus. Catching his own sentimentality, Abu Bashir chuckled at the morbid memory as though the echo of his laughter might erase it.

When current Palestinian armed resistance fighters recall the incentives behind their defiance of Israeli settlers and military power, it is almost always the killing of someone dear. In Jenin, the senior armed resistance leader and fighter, Nidal Khazem, killed last March before his 29th birthday, shared a similar sentiment. “They come here and kill our friends,” he told Mondoweiss months before his own brutal execution. “When they killed my cousin,” Khazem confessed that evening, “I and five other fighters joined [the armed resistance].”

These historical continuities bind the resistance to the Nakba with contemporary Palestinian resistance. It is a refusal to be erased but also a desire to avenge your loved ones. What is today known as Israel’s “targeted prevention” practice of liquidation has just been a continuation of the past. What becomes evident is that the smell of death and the presence of executions is not a memory but a slow slaughter.

Never again

In 2021, during the Unity Uprising, settler lynch mobs in Haifa, Lydd, Yaffa, and Tel Aviv put marks on the doors of Palestinian apartments and homes, to easily identify them for lynching and assault.

It was one of the first times that I witnessed Palestinians in the West Bank offering their homes to Palestinians with Israeli citizenship. “You can come sleep in Ramallah until it’s safer to go back home,” I recall telling a few friends.

That utterance conjured a similar scene of the Palestinians escaping the 1948 massacres and the violence of Zionist militias. The Palestinians, now refugees, tried to find asylum with their families in neighboring towns thinking it was temporary. More than seven decades later, Israel is actively targeting the children of those refugees inside the camps.

On Monday, May 15, Israeli military and undercover special operations forces invaded refugee camps across the West Bank, ranging from Balata and Askar near Nablus, to Aqbat Jabr in Jericho in the south, and Jenin refugee camp in the north. According to local news reports and eyewitnesses who spoke to Mondoweiss, the invasion encompassed at least eight of the 19 refugee camps in the West Bank. In the week leading up to the 75th commemoration of the Nakba, between May 9 and 15, Israel killed 40 Palestinians, bringing the number of Palestinians killed this year as of the time of writing to 153, 26 of whom were children. That week and the weeks, months and years before it, were a morbid demonstration of the Nakba’s meaning.

It is the implication of that meaning–that the drive to expel us from our lands is ongoing–which Palestinians continue to resist. As 43-year-old Fuad Khuffash told Mondoweiss on March 8, almost two weeks after his shop was burned down during the settler pogrom in Huwwara: “The expulsion and displacement of Palestinians [and making them] into refugees was a mistake in 1948, and we will not allow it to repeat itself.”

“We are planted here and rooted here. This is our land and our home,” Khuffash said, reflecting on the pogrom in Huwwara. “The Nakba is something that will not repeat itself in the history of the Palestinian people,” he promised.

(Mariam Barghouti born in Atlanta, Georgia, June 23, 1993, is a Palestinian-American writer, blogger, researcher, commentator and journalist. She hails from Ramallah. Courtesy: Mondoweiss, an independent website devoted to informing readers about developments in Israel/Palestine and related US foreign policy.)