Shankar Guha Niyogi, the legendary trade union leader of Chhattisgarh Mines Shramik Sangh (CMSS) remains a largely marginalised, if not forgotten, public figure despite his achievements and contribution to workers and tribal struggles in India. This marginalisation largely results from the failure of post-Niyogi CMSS to live up to the legacy of its heyday during the 1980s as well as due to neglect on part of the broader trade union movement to take cognizance of the work and learn from the experiments of CMSS.

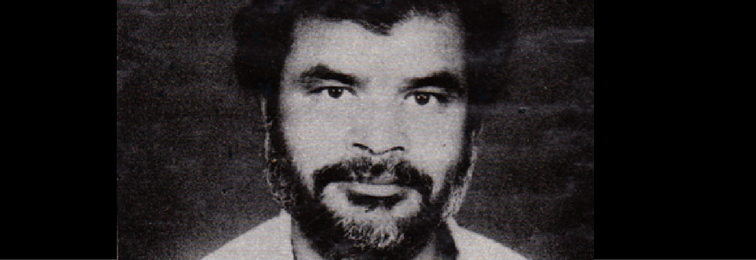

Shankar Guha Niyogi was born on 14 February 1943 in Naogaon district of Assam to a middle class family. He completed his initial education in Asansol, West Bengal, where he came in contact with the life of coal-mine workers and later got associated with communist politics during the Food Movement in Bengal in 1959. Niyogi eventually enrolled in the prestigious Jalpaiguri Engineering College, but left it soon and migrated to Bhilai—present day Chhattisgarh—to work in the Bhilai Steel Plant in the mid-1960s. From here began his career as a trade union leader and a grass-root communist activist.

Niyogi initially started to organise co-workers in the steel plant against the harsh working conditions which led to his expulsion. Between the time he was thrown out and the time he became leader of the CMSS, he led a roller-coaster of a political life. He was member of undivided CPI, and joined the CPI-M after the 1964 split in the communist movement. Later, he was attracted to the Naxalbari movement, only to be expelled from the newly-formed organisation for his critique of CPI-ML’s position on boycott of mass organisations and mass line. Left on his own and branded a “Naxalite” by police, Niyogi went underground and lived under the alias Shankar (his original first name was Dhiresh).

While underground, evading the MISA-enforcers in the immediate aftermath of Emergency, Niyogi lived a nomadic life, traversing the towns and villages of Chhattisgarh. He lived among the Adivasis of Bastar, Gadchiroli and Durg, learned their language and shared their livelihoods. A Bengali with a privileged education and background was able to de-class himself in the Marxist sense as he worked as a manual mineworker and agrarian labourer, and laboured in the forests, or grazed and sold goats, and caught and sold fish.

As a mineworker in the Danitola mines, Niyogi continued his efforts to build a people’s organisation in surrounding villages and organise workers. During this time, he met his future wife, Asha, who belonged to the Gond community. Initially apprehensive of his “outsider” status, Niyogi was able to convince her, as well as villagers and co-workers, that he was “one of their own”, through his serious efforts to integrate such as adopting the local cuisine, language and tradition and was able to bridge the cultural gap.

In his “on-the-run” days, Niyogi also brought out a few issues of a magazine called Sphuling (Spark) inspired by the Bolshevik mouthpiece, Iskra. He also came in contact with a group of revolutionary communist intellectuals led by Dr B.S. Yadhu in Raipur. He would passionately participate in discussions of the group, which gave him clarity on Marxist theory. Later, he edited a pamphlet on Marxist theory titled “Marxvaad Ke Mool Sutra” (Basic Tenets of Marxism) which sought to make it accessible. In short, he was the archetype or living embodiment of the Marxist concept of praxis. When finally he was arrested under MISA during the Emergency, and subsequently released in 1977, he moved to Dalli-Rajahara and here began his most remarkable journey.

CMSS: a unique experiment in trade unionism

In a lot of ways, the life of Shankar Guha Niyogi cannot be separated from the organisation he built and for which he became famous, i.e. CMSS. Formed in 1977 by contract workers in the Dalli-Rajahara mining zone, Niyogi was approached to accept charge of its institutional and organisational growth. The trade union primarily consisted of Adivasi manual mineworkers, with Niyogi as its secretary and Sahadev Sahu, a truck driver, as its president. The CMSS had eighteen departments which included environment and health.

The CMSS continues to be a unique experiment in the history of the trade union movement in India, and probably the world. The CMSS did not limit itself to economic struggles of mineworkers and villagers but extended its activities to include their socio-cultural life. Niyogi integrated the trade union with almost every fabric of local society and thus redefined the meaning of trade unionism.

The motto of the CMSSS was Sangharsh aur Nirman (Struggle and Construction) and its flag a mix of green and red, denoting the unity of peasants and workers. Under this slogan, the CMSS undertook many remarkable campaigns, which empowered the local community. Apart from struggling over usual trade union questions of wages, working conditions, resisting expulsion, contractualisation, struggling against mechanisation and for social security benefits, the union also campaigned for healthcare and built a remarkable 50-bed hospital. It campaigned for education and built six schools; campaigned for raising awareness about environmental issues, ran an anti-liquor campaign and helped develop a distinct revolutionary Chhattisgarhi identity around Veer Narayan Singh, an Adivasi leader martyred during the 1857 revolt.

Niyogi and the CMSS were able to break free from the capitalist-modernist separation of different aspects of human life which divides it in separate and seemingly independent categories like economy, politics, health, education, environment, art and culture etc. Integrating all the above spheres of human life into a whole, the CMSS presented a coherent world-view of struggle, resistance and construction of a new society.

For example, if we take the question of health, CMSS’s decision to build a hospital arose from the unfortunate death of a woman during childbirth. But the question did not end there, it extended to building a consciousness around health. To do this, the CMSS ran a campaign called “Let’s Struggle for Health” under which streets were cleaned, waste management was taught and the health benefits of cleanliness was spread. Similarly, the anti-liquor campaign was propagated not merely by citing the economic, but also the health and cultural costs, such as domestic violence. The campaign to save the environment was not merely about planting trees or saving the forests, but it was also a critique of the capitalist development model with Bhilai Steel Plant as its embodiment. It was a critique of the separation of Adivasis from their traditional livelihood practices and their rights over the forests.

CMSS and Niyogi raised every important question of human existence and framed it in the language of everyday life by connecting them with the everyday experiences of people. It employed every form of campaign strategy to raise consciousness around issues that mattered. With the complete participation of common people in the CMSS, its creativity was bound to explode and it become a magnet that drew more people towards it. The Dalli-Rajahara area, which was the base of CMSS, soon began to attract doctors, film-makers, artists, journalists, trade union leaders, musicians, alternative development practitioners, writers and so on. People like Ilina Sen, Binayak Sen, Anand Patwardhan and a range of civil society activists found their way to Dalli-Rajahara; some to work, some to write and some merely to live. Niyogi had even planned to setup a Workers University in Danitola, but it did not materialise due to his untimely death in 1991.

Even though the CMSS was able to organise and empower the local population and was hugely popular in urban spaces, there was a serious limitation to the movement, which proved detrimental after the death of its charismatic leader. The union and the movement was a deeply Marxist one but failed to develop a well-charted political programme for a broader political change. Perhaps Niyogi was expecting to transplant the CMSS model of activism to other areas, an opportunity which came in the form of several invitations to start a branch of the union by people of other states and regions.

Shankar Guha Niyogi was murdered in his sleep on 28 September 1991 at the behest of industrialists. His martyrdom coincides with the birth anniversary of Bhagat Singh. Incidentally, one of Bhagat Singh’s closest comrades, Manmathnath Gupta, was a huge supporter of Niyogi and visited Dalli-Rajahara many times. He wrote in a letter to a friend in 1992, “I was very close to Niyogi for 7 years. I used to visit him every year, not once but many times and used to address a lot of public meetings. He was a Marxist, but he had his own method. When he saw that the workers were forgetting Revolution because of alcohol, he organized female workers against it in a Gandhian way.” (Source: Samay Samvad by Sudhir Vidyarthi.)

Niyogi and the CMSS were able to solve the old question of what should come first, culture or politics. He showed that both can go hand-in-hand and there is no need to see them in contradiction. Today, the Indian masses are facing unprecedented distress on the economic front. In order to counter the “resentment” of masses, the ruling dispensation has unleashed a vast cultural war machine, whose job is to spread communal hatred and create a Hindutva cultural consciousness whose defining features are intense hatred for Muslims and Dalits as well as for socialism, feminism, even liberalism.

In order to counter the political-economic attack on Indian masses and normalisation of Hindutva discourse, a multi-pronged strategy has to be adopted in which both the questions of economics and culture have to be equally focussed. Niyogi and CMSS probably provide some intellectual and practical resources to do this.

(The authors are research scholars at JNU. Articlle courtesy: Newsclick.)