Referring to India’s relations with the outside world, Mahatma Gandhi wrote in his weekly Young India in 1921: “I want the cultures of all the lands to be blown about my house as freely as possible. But I refuse to be blown off my feet by any….My Swaraj is to keep intact the genius of our civilization. I want to write many new things. But they must be all written on the Indian slate. I would gladly borrow from the West, when I can return the amount with decent interest.” This virtually sums up the dominant orientation of the Indian Nationalist Movement that culminated in freedom in 1947. It was clearly nationalist, yet maintained the highest standards of internationalism, sometimes under grave provocations.

All the nationalist struggles – launched in parts of Asia, Africa and Latin America – against modern imperialist domination have faced a peculiar dilemma. What should be their attitude to forces of Modernity? For the non-European societies, Modernity had a Janus-like character. It meant both progress and slavery.

From the 18th century onwards began a new global trade in ideas. Most such ideas emanated from Europe, for obvious reasons. In time to come these ideas got neatly packaged as a part of Modernity. Bur this package contained very contradictory ideas. On the one hand, there were the ideas of Progress, Rationalism, Universalism and Secularism, connected to the Enlightenment, an intellectual-philosophical movement that started in Europe. From the same direction, however, also flowed imperialism and colonialism, domination of the world by the West, and a shameless justification of that domination. This really placed the rest of world in a dilemma. An acceptance of the package entailed a loss of freedom. But a rejection of the package contained the risk of isolation in an increasingly globalized world.

The leaders of the Indian national movement, from the very beginning refused to opt for the given options of a total acceptance or a total rejection. Rather they disaggregated Modernity itself. They accepted the ideas of the Enlightenment as part of collective human heritage. But they completely rejected imperialism and colonialism as dangerous and harmful for the society and economy of the colonies. This became the dominant trajectory of the Indian national movement in its relations with the outside world. The leaders of early Congress articulated their views and took a stand on the major international questions of the day.

From the very beginning, the Congress leaders critiqued the British policy of annexation and conquests abroad. When the British annexed upper Burma (present-day Myanmar) and made it a part of British India, the Congress leaders opposed it. Their opposition was only partly based on the expenses involved in such conquests. It also emanated out of a respect for the territorial integrity of another country.

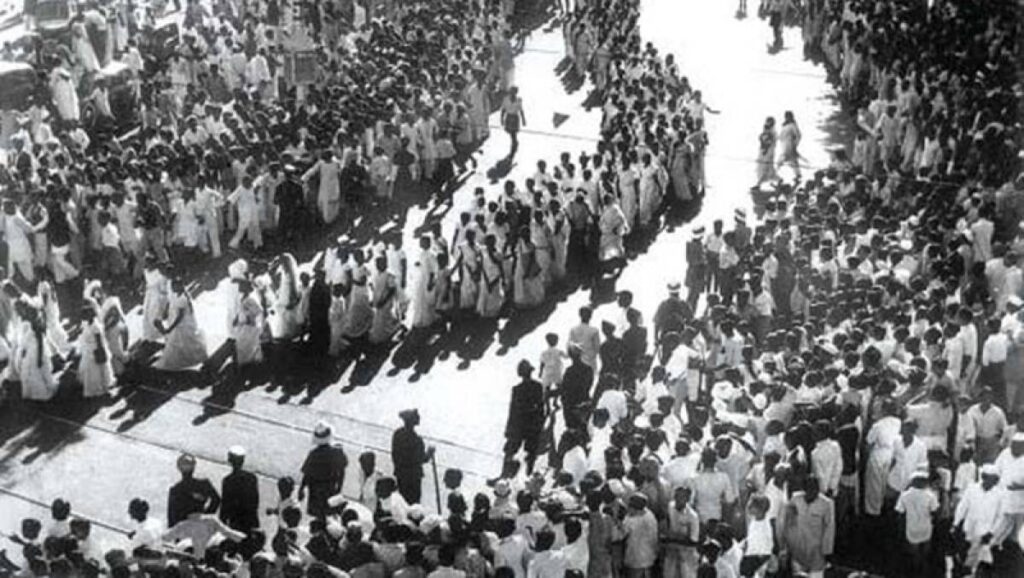

At the beginning of the 20th century these critiques culminated in a concrete policy of non-interference in another country. When the British tried to interfere in the affairs of Persia and Turkey, the Congress leaders voiced their opposition to it. They were particularly agitated on the fate of Turkey because the Caliph, the Sultan of Turkey, was also considered the spiritual leader of Muslims all over the world. At its 1912 session, the Congress president expressed the “profound sorrow and sympathy” felt by all the non-Muslim Indians for their Muslim brethren for the misfortunes of the Caliphate. Later, at the end of the First World War, Gandhi actually led the Khilafat movement in support of the Khalifa. The movement was fought for a restoration of the power and prestige of the Khalifa of Turkey, which had been promised by the British during the War, and denied subsequently.

Once the national movement came under the active leadership of Gandhi, with Jawaharlal Nehru as his deputy, it acquired truly global dimensions. The new perspective was based on a championship of the twin values of freedom and peace everywhere, and for every country. Indian independence was seen as an important component of this project of world peace.

It was actually in 1921 that Congress stated its own independent foreign policy. Delinking itself from the foreign policy of the British, Congress highlighted peace, freedom and global cooperation as the necessary building blocks in its foreign policy. This was perhaps the first example of a colony, under imperialist domination, declaring its own independent foreign policy. Gandhi declared: “While we are making our plans for Swaraj, we are bound to consider and define our foreign policy. Surely we are bound authoritatively to tell the world what relations we wish to cultivate with it.”

Once Congress dissociated itself from the British foreign policy, it began to support freedom struggles by other Asian countries against European imperialism. It expressed solidarity with the struggles of Arabs, Egypt, Burma, Sri Lanka and China. Gandhi began to talk of an Asian Federation, committed to freedom and peace. “Common lot, no less than territorial homogeneity and cultural affinity is bringing the Asiatic races wonderfully together, and they now seem determined to take their fullest share in world politics.”

Nehru attended the International Congress of Oppressed Nationalities in Brussels in 1927. This really internationalized the Indian struggle for freedom. India and China came close together for the first time. The national movement now began to openly express solidarity with all the struggles against Western imperialism. At Nehru’s initiative, Congress affiliated itself with the League against Imperialism set up at Brussels. Congress now declared from its platform that the Indian struggle was part of a great world struggle against the very system of Imperialism.

In the same year, 1927, Nehru visited the Soviet Union on the occasion of the 10th anniversary of the Russian Revolution, and was very impressed with the transformation in the social conditions in a short span of time. He wrote a whole book on the USSR and transformed the way Indians had looked upon Russia . Till then Indians had looked at Russia through the British lenses, in which Russia appeared as an aggressive expansionist power to be feared. The British foreign policy in India had been largely shaped by a kind of Russio-phobia. Nehru demolished this myth and provided a new vantage point from where the Soviet Russia appeared more like an ally rather than an aggressor. Nehru wrote: “Ordinarily India and Russia should live as the best of neighbours with the fewest points of friction. The continuous friction that we see today is between England and Russia, not between Indian and Russia. Is there any reason why we in India should inherit the age-long rivalry of England against Russia? That is based on greed and covetousness of British imperialism, and our interests surely lie in ending this imperialism and not in supporting and strengthening it.”

It was also at Brussels that Nehru became aware of the problems of Latin Americans, groaning under the weight of American imperialism, through his contacts with the Latin American delegates. He prophesied in 1928: “…the great problem of the near future will be American imperialism, even more than British imperialism, which appears to have had its day and is crumbling fast. Or, it may be, and all indications point to it, that the two will unite together in an endeavour to create a powerful Anglo-Saxon block to dominate the world.”

The sum total of the foreign policy as practiced by the national movement till the 1920s was a combination of Indian nationalism with internationalism. Nehru realized that the British imperialism could not be defeated till Imperialism as a whole was dismantled. It was in this sense that each colony of Asia and Africa needed to fight against its imperialist power but also fight collectively against Imperialism as a system. The two struggles, the nationalist and the global, needed to complement each other in order for both to be successful. But certain important developments in the next decade created new challenges for this perspective of the Congress combining nationalism with internationalism and stretched it to its limits.

The world in 1930s experienced the emergence of a dreadful and horrific political movement generically called Fascism. It was based on totalitarianism, denial of individual freedom, cult of a supreme leader, militarization, and the total subordination of society to a single point of authority. All the major values and aspirations of the modern human civilization were threatened by Fascism. The threat became all the more serious when this movement captured state power in Germany and Italy and maintained an active presence in many other European countries. A variant of Fascism also developed in Japan and captured the state. Fascism was the new global aggressor. It threatened not just the world but also the old leaders of the world, liberal democratic and the Communist alike. The Fascist take-over of the world was a real and dangerous possibility in the 1930s.

This new development changed all the old equations. It also created a major dilemma for the national movement. It was clear that, given the opportunity, Fascism would decimate the old imperial powers, England included. Should the Indian national movement therefore welcome and support the Fascist Juggernaut? The conflict was clearly between the short-term and the long-term goals. Fascism might eliminate the old imperialists and thereby enable India to gain freedom. But it would be impossible to hold on to that freedom in a world dominated by Fascism. Even so, the emergence of Fascism did offer an opportunity to India to get rid of British imperialism. Some of the Indian leaders were attracted to this line of thinking. Some others, however, argued that India should forego, or at least suspend the national fight for its independence and concentrate on the global struggle against Fascism.

This development put internationalist vision nurtured by the Indian national movement to a severe test. The Second World War started between the forces of democracy and freedom on the one hand (England, USA and USSR, the Allied powers), and those of Fascism on the other (Germany, Italy and Japan, the Axis powers). England went ahead and unilaterally declared India, as a British colony, to be a party to War from the side of the Allied powers. This created an immediate dilemma for the leaders of the national movement. One option for the leaders of the national movement was to side with the forces of democracy and freedom and play a role in ridding the world off the menace of Fascism. The world as a whole was threatened by it. The trouble however was that the same forces which upheld freedom and democracy globally, suppressed it nationally. England in partnership with USA and USSR fought the Axis powers to uphold freedom and democracy. But it denied the same democracy and freedom to the people of India. What should India do? So far, it had generally been possible to combine its national commitment with global priorities. Indeed national freedom was a stepping- stone towards establishing global peace. But the emergence of Fascism and the particular context of the world war did not allow for this congruence between national and international commitment. The national commitment to freedom demanded a struggle against British imperialism. But an international commitment to peace and democracy demanded a support for the British engaged in a global war against Fascism. What to do?

It was at this point that Nehru, with support from Gandhi, rose to the heights of statesmanship and took a stand which was fully consistent with the high moral standards the national movement had set for itself. Nehru wrote: “We want to combat Fascism. But we will not permit ourselves to be exploited by imperialism, we will not have war imposed upon us by outside authority”. India was desperate to support the force of freedom against Fascism. But it was absurd for England to expect India, a country in imperial subjection, to fight for the freedom of the world. One had to be free and democratic to be able to fight for freedom and democracy. Nehru insisted that India should be immediately set free, and then an independent India will play its part in the global war against Fascism. Though initially reluctant, soon Gandhi too came round to this view.

This was the period of multiple dilemmas. Gandhi faced an acute dilemma on what stand to take on the Jewish question. He strongly disproved of the persecution of the Jews. Yet he felt that the in mass settling of the Jews in Palestine was unfair to the Palestinians. One act of persecution of the Jews, did not justify their encroachment on the lands other people. In a remarkable statement in 1938, he wrote: “My sympathies are all with the Jews. … They have been the untouchables of Christianity. The parallel between their treatment by Christians and the treatment of untouchables by Hindus is very close. Religious sanction has been invoked in both cases for the justification of the inhuman treatment meted out to them …. But my sympathy does not blind me to the requirements of justice. The cry for the national home for the Jews does not make much appeal to me …. Palestine belongs to the Arabs in the same sense that England belongs to English or France to the French. It is wrong and inhuman to impose the Jews on the Arabs.”

It was also during this period that Gandhi developed the practice of making appeals to the people of other countries. He wrote letters to ‘every Briton’, ‘every Japanese’ and also to ‘American friends’. He chided the people of Japan for Japanese aggression in China: “…though I have no ill-will against you, I intensely dislike your attack upon China. From your lofty height you have descended to imperial ambition. You will fail to realize that ambition and may become the authors of the dismemberment of the idea of Asia….I grieve deeply …. your merciless devastation of [China] that great and ancient land.” In sheer desperation, Gandhi even wrote a letter to Hitler, imploring him to prevent the War “which may reduce humanity to a savage state.”

The War ended in 1945 in a victory for Democracy. Fascism was conclusively defeated, though not fully eliminated. The end of the War initiated a phase of decolonization the world over. Between 1945 and 1960, around 120 former colonies of Asia and Africa became independent. The imperialism of the old type became a thing of the past. The end of the War opened a new chapter in human history. The old optimism of human progress and freedom, clouded and buried under multiple layers by Fascism, resurrected again to enlighten and inspire the world in its quest for a bright future. It once again seemed possible that all of humanity might be able to realize the goal it had set for itself since the 18th century. Old optimism began to look feasible. The Indian national movement had played a significant role in altering the map of options facing all of humanity.

This briefly speaking, is the major legacy of the national movement. The edifice of a foreign policy in independent India was based on the foundations laid during the national movement. The general debates on foreign policy tend to invoke the categories of ‘idealism’ or ‘immediate pragmatic necessities’ in a either/or kind of binary. The experience of the national movement was that the immediate pragmatic interests made sense only when placed in a larger setting – of a vision of a world order based on peace and cooperation. This was the big picture at the end of the War. With some modifications, this continues to be a big picture even today. India contributed in a significant manner, not just to the articulation of the big picture, but also to its realization, however partial. Whether India is still ready to contribute to its realization today, depends on its current leaders. But there is no doubt that on this front, we Indians have an extremely rich legacy and we should be proud of it.

[The writer teaches history at Ambedkar University, Delhi.]