Anil Nauriya

(This essay was written in 2015, as a review of Nayantara Sahgal’s book, “Nehru’s India: Essays on the Maker of a Nation”. We are publishing an edited version of this essay, because it has become even more relevant today.)

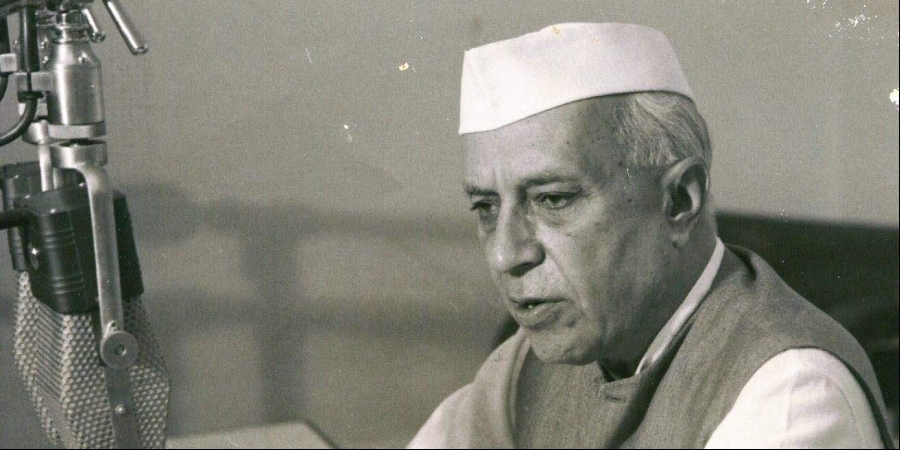

If one scans the political landscape of India in the 20th century for a personality who was both a patriotic front-rank participant in the freedom movement led by Mahatma Gandhi and simultaneously sensitive to the need to oppose international fascism and its domestic Indian manifestations, that man was Jawaharlal Nehru. He has an obvious relevance for India and the world in the 21st century. As Acharya Narendra Deva, the doyen of Indian Marxist Socialism, had noted of Jawaharlal Nehru in an essay in 1946 : “There is no doubt that the personality of Gandhiji and the mass movement initiated by the Congress under his leadership attracted wide attention abroad and created an interest in Indian affairs, but it is also true that if the Congress had not under Jawaharlalji’s inspiration evinced an interest in world affairs and had expressed its keen desire to ally itself with the progressive forces of the world, the world would not have shown that abiding and deep interest which it has shown…. The fact that he has become today an international figure is symbolic of the realisation that he has won international recognition for India and the fact that he is an idol of the Indian masses is symbolic of the Congress having won the affection and loyalty of the masses. For, we must not forget that Jawaharlalji’s life and activities are indissolubly bound up with the Congress and that he has completely identified himself with it. There have been occasions when he has vitally differed from certain policies and decisions of the Congress, but when once a decision is taken, he has given his whole-hearted support to it.”(1)

It is not an accident that Nehru has become a hate-figure for Indian religious sectarianism and the related political majoritarian-sectarianism which goes together with it. There has been a systematic and venomous campaign against Nehru particularly from the early 1950s when Nehru led Parliament to carry out reforms in Hindu law.

In this context, Hartosh Bal, the political editor of Caravan magazine, has made an insightful comment on the Hindu law reform legislation of the 1950s: “Ambedkar quit the Cabinet well before they were passed…. But without Nehru none of these reforms would have ever become reality. Ambedkar on his own could not have taken on the Hindu Right…. Given this, it is ironical that today there are enough to speak for Ambedkar or for the Hindu Right, and very few for Nehru.”(2)

While the present-day Congress cannot entirely be separated from the legacy of the pre-freedom Indian National Congress, yet the former has distinct characteristics and must be organisationally distinguished from its historical predecessor. Moreover, with the current decline of the Congress, we need to remind ourselves that many of us outside that organisation are also legatees of the space created and occupied by Indian nationalism since 1885.

There were a wide range of issues that had engaged the pre-independence Indian nationalists: from Dadabhai Naoroji to Romesh Chandra Dutt on the economic aspects; to Mahadev Govind Ranade on social aspects who in turn had inspired both Gopal Krishna Gokhale and Gandhi; to Gandhi, Abbas Tyabji, Motilal Nehru, C.R. Das and Tagore on civil liberties questions arising especially out of the 1919 events and after and Asaf Ali’s inquiries on the NWFP and Bannu raids in 1938; to Narendra Deva and the language-related contradictions in the education system pointed out by the Education Committee headed by him in the United Provinces in 1938–39; to the Rashtriya Stree Sabha of the 1920s, Desh Sevika Sangh of the 1930s, Sarojini Naidu and socialists Kamladevi Chattopadhyaya, Rama Devi and Malati Choudhury on the issue of the relation between nationalism and gender; to the entire legacy of constructive work associated with the freedom movement, as represented for example, by Thakkar Bapa, Kaka Kalelkar, Ginwala, Mithu Petit, Jugatram Dave, Khurshed Naoroji, B.F. Bharucha, Bibi Amtussalam, Perin Captain, Walunjkar, Zakir Husain, Asha Devi and Aryanayakam, and countless others.

The split in the Indian National Congress in 1969 and the dissolution eight years later of the Congress (O), with its merger into the newly-formed Janata Party in 1977, had the undesirable consequence that the entire Congress space came to be occupied by Mrs Indira Gandhi’s party, then known as Congress (I). It is this latter party which has in recent years been receding politically. In the circumstances, it should not have been difficult to foresee that unless those outside this party, who still saw themselves as legatees of the Indian freedom struggle as represented by the pre-freedom Indian National Congress, organised themselves, the vacuum left by the decline of the Congress would inevitably be filled by other forces, especially the Hindutva forces.

The anti-Nehru space in India is populated not merely by Hindutva but also often by the epigones of Rammanohar Lohia. The answers that the latter-day Socialists in the Lohia years provided to some of the social, linguistic and cultural issues Lohia raised are not necessarily so complete or final that they cannot be re-thought.(3) On other issues too, remaining confined to some of the post-independence Lohia–Nehru controversies, especially of the 1960s and the thinking that emerged then, has constricted the intellectual growth of the socialist movement. A similar point was once also made by the late Kishan Patnaik in the socialist journal Janata in 1980.(4) It is also worth recalling here that the late Surendra Mohan, in an introspective article written for Janata, had once pointed to the connection between the negativities in the Opposition politics of the late sixties and the negativities of the post-Shastri establishment.(5)

Another aspect of the matter is worth appreciating. The writings of Lohia and the politics of Lohia need, to some extent, to be distinguished as these are not necessarily congruent. Speaking generally, the writings of both Lohia and JP may be rated considerably higher than their politics, especially Lohia’s politics in the 1960s and JP’s in the 1970s. [Incidentally, this is the reverse of what is true in the case of Mahatma Gandhi whose praxis would often race ahead of his writings, phenomenal though these themselves were; Gandhi himself recognised this when he said that his writings could be burnt for all he cared and that it was his life that was his message; in the same vein, Nehru too had once observed how much greater Gandhi was than his “little books”.]

Every movement requires periodic renewal; its dominant doctrines and practices need to be reconsidered in the light of experience. The political alliances Lohia forged and also the thinking associated with these alliances certainly need to be re-thought in the light of subsequent experience and also the changed circumstances in which the Congress is no longer the force that it used to be. The Socialist alliance with the Jana Sangh in the run-up to the General Elections of 1967 had opened the route to further such unthinking linkages by Jayaprakash Narayan in the mid-1970s and by V.P. Singh in the late 1980s. The remedies sought by Lohia, JP and V.P. Singh, and especially the manner in which these were sought, may have proved worse than the disease. Few precautions were taken by them in the forging of their strategies and no adequate steps taken for the ideological training of cadres. Even if such precautions had been taken, it should have been obvious that aligning with reactionary forces, whether tacitly or otherwise, would have long-term deleterious ramifications for the country.

Contemporary India must positively re-engage with the legacy of Jawaharlal Nehru in his role as a great fighter for Indian freedom and connect with him just as, say, the founders of the Congress Socialist party had. The founders of the Socialist movement did not see themselves as being apart from Nehru. Narendra Deva, in his presidential address at the first session of the of the All-India Congress Socialist Conference at Patna on May 17, 1934, had in his opening words referred to Nehru in the following terms: “My task is made all the more difficult by the absence of our beloved friend, Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru, whose absence today we all so keenly feel and whose valuable advice and guidance would have been of immense value to us on this occasion.” Twelve years later, Narendra Deva wrote a perceptive appraisal of Nehru. Narendra Deva recognised that “Jawaharlalji took great interest in class-organisation. He was elected President of the All-India Trade Union Congress in the year 1929 and it has been his constant endeavour to make the Congress interest itself in the economic struggles of the workers. He tried to bring economic questions to the forefront. The resolution of Fundamental Rights passed at the Karachi Congress in 1931 was his contribution. His activities brought about a general radicalisation of political thought in the country.”(6)

So far as the State was concerned, Nehru was committed to its religious neutrality as postulated by the Karachi resolution of 1931 which he had taken the lead in drafting. As Narendra Deva points out, this resolution was Nehru’s “contribution”. On Nehru’s personal attitude toward religion, Narendra Deva writes: “Religion in its institutional form is repugnant to him as it is the bulwark of reaction and the defender of status quo. Its function in society has been to make social inequalities less irksome to the lower classes. But he has no quarrel with that purer form of religious faith which inspires the conduct of individuals. He, however, believes in ethical social conduct and has a deep sense of human values.”(7)

It was Nehru who, as the Congress President in 1936, had reorganised the Congress headquarters and introduced an internationalist perspective into it. Nearly 40 years younger to Gandhi and some 19 years to Nehru, Rammanohar Lohia wrote to the latter on May 23, 1946: “Please don’t forget that you and another have influenced men like me so much that there never has been a place for a third nor ever shall be.” A photocopy of Lohia’s letter to Nehru was published by the socialist Bhola Chatterji (1922–1992) in an article in Sunday magazine some decades ago.

The socialist leader and intellectual, Madhu Limaye, who was close to Lohia and nearly three decades younger than Nehru, was conscious of the need “to take an objective view and keep out my personal likes and dislikes, prejudices and predilections”; he refers to Jawaharlalji as the “uncompromising sentinel of Independence” and acknowledges that he “gave a new orientation to (the) Congress policy and programme”; and that “he championed the cause of the peasantry” and “took up the case of the workers working in mines and the factories who were being treated as slaves”.

Jawaharlal Nehru is an intrinsic part of the legacy of Indian freedom; no contemporary Indian politics that seeks to take India forward can be defined by excluding him.

On inter-communal questions, which have a bearing on the very definition of India, Nehru’s record is par excellence and second only to that of Mahatma Gandhi. In spite of the bitterness ensuing from the country’s partition in 1947, the Nehru dispensation maintained inter-communal peace, with the first major riot occurring only in the early sixties.

In this context, it is necessary to energetically counter the attempts of Hindu Mahasabha, the Bharatiya Janata Party, the RSS and their associate organisations to malign and discredit Gandhi and Nehru. The vilification tendency has now been in evidence for several decades; but it has lately assumed a virulent character. The RSS has made virulent attacks on Gandhi because they believed the Mahatma was their direct enemy as he did not disclaim Hinduism and occupied the socio-cultural political space which they believed was theirs. In addition Gandhiji’s advocacy of ‘Ishwar-Allah tera naam’ stood in direct opposition to their idea of Hindu and Muslim communities. The Mahatma’s appeal to remove hatred from hearts and minds, and to love all humanity, including Muslims and Christians, was a direct challenge to their social philosophy. To their dismay and disgust, the Congress under Gandhiji had won the people’s hearts and had a pan-Indian and international following. There was no chance or possibility to remove Gandhiji from that political space except by way of killing him, which is why attempts to assassinate Gandhi preceded partition. Post-assassination, direct attacks on Gandhi have been replaced with more subtle strategies that seek to invoke Gandhi for matters such as cleaning-up while ignoring his pluralism and mocking his humanism. The direct attacks are now made mainly by the Mahasabha and its related organisations which have even sought to glorify Gandhi’s assassins.

As regards the Sangh targeting Nehru, Kumar Ketkar writes that “Nehru came on the radar of the Sangh Parivar only after Gandhiji declared that he would be his successor.” Gandhi and Nehru were “in complete agreement” on “the most important and explosive issue of communalism”.(8)

Another issue on which the intelligentsia must re-engage positively with Jawaharlal Nehru is that he was the builder of post-independence India. Nehru respected Parliament and urged the judiciary, nurtured in colonial times, to recognise social concerns in a changing India. It was Nehru who got the Congress committed to a socialistic pattern of society in its session at Avadi in 1955. The building up of the public sector enabled India to hold its own for long in a world that various international powers sought to bend to their own image. Stupendous efforts were made under Nehru to reduce India’s external dependence on oil. How vital this effort was may be gauged from the lengths to which Western powers went in opposing similar Iranian efforts under Prime Minister Mossadegh against whom a successful coup was organised in the 1950s. The building up of an independent public sector had other ramifications as well. The emphasis on research and development, 90 percent of which was done in the public sector, induced a tradition of self-reliance, partly squandered by later regimes. In the case of drugs, this tradition has enabled Indian firms today to be prime suppliers of relatively low-priced vital medication to countries with similar problems as ours, such as countries in Africa.

Nehru laid great emphasis on science and technology. In this context, it is worth mentioning the explanation given by the famous scientist, J.B.S. Haldane, for moving to India in the 1950s: “One has the absolute impression of being in a highly civilised community… I feel far more at home there than I do in some European and most American cities.” (9)

Nehru is often criticised for neglecting agriculture at the cost of heavy industry. But it is forgotten that it was Nehru who led from the front in breaking the back of the 150-year-old zamindari system within a democratic framework. At least two rounds of land reform legislation, at the onset of the fifties and sixties, took place under Nehru’s leadership. Daniel Thorner, who had devoted much of his life to studying Indian land and agriculture, writes: “It is sometimes said that the (initial) Five Year Plans neglected agriculture. This charge cannot be taken seriously. The facts are that in India’s first twenty-one years of independence more has been done to foster change in agriculture and more change has actually taken place than in the preceding two hundred years.” (10)

It will be readily conceded, of course, that more could have been done and still needs to be done with regard to irrigation, proper land and water management and liberating diverse regions of India from the cycle of flood and drought.

Another important contribution of Nehru, which is also being much maligned today, was his foreign policy initiatives. Among the most important contributions of Nehru in this regard was his non-alignment. The United Kingdom was particularly upset with Nehru’s stance in the Suez crisis and the Anglo–French attack on Egypt in the late fifties. While there were some foreign policy failures also, as in the case of China, even in this latter case, Nehru’s mistakes have been exaggerated such as the one-sided description in Neville Maxwell’s India’s China War. It is all to the good therefore that some correctives have emerged in recent years, including a book edited by the late Air Commodore Jasjit Singh and a very perceptive paper by Nirupama Rao.(11) At a recent Indo-African summit in New Delhi, the tendency to ignore Nehru’s contribution was carried to the point where the African dignitaries had to remind the current Indian government of the shared vision and positive contributions of Gandhi and Nehru to Africa and its struggles.

The extent to which Nehru moulded the post-independence Congress may be gauged from remarks that Jayaprakash Narayan made in July 1964, a few weeks after Jawaharlalji’s death. JP was reported to have said that leaving the Congress in 1948 to form the Socialist Party was a mistake committed on account of “the wrong assessment of the character of the Congress”. According to JP, most of his partymen thought at that time that the Congress would slowly develop into a conservative-cum-liberal party just like “what the Swatantra Party is today”. But history belied this assessment.(12) [Ironically, the then assessment may have provided an accurate description of the later post-Emergency Congress and especially towards the last two decades of the twentieth century.]

The currently dominant Indian intelligentsia’s attitude towards Nehru induces some of them into making overt and covert arrangements with the BJP and its associates, just as they had done in the past with BJP’s predecessors. This predilection needs rectification. For example, in the case of the Socialists, the Draft Platform of the Socialist Party in 1972 had ruled out any modus vivendi with the Jana Sangh. Yet this formulation was abandoned within a couple of years of it being advanced.

Those who consider themselves to be inheritors of the heritage of the Indian freedom struggle, especially those belonging to the socialist tradition, naturally speak of such figures as Gandhi, Narendra Deva, Jayaprakash, Yusuf Meherally and Lohia. They have no difficulty also in seeking bridges between the social struggles of Gandhi and of Ambedkar. Although the latter was an outsider to the political struggle for Indian freedom, his social legacies are correctly seen by Socialists as being convergent with their own objectives, as Lohia himself recognised in the fifties. Why then the contemporary reluctance of a section of Socialists to recognise their obvious affinities and convergences with Jawaharlal Nehru? It is difficult to avoid the conclusion that Nehru is unjustly excluded for subjective and even irrational reasons connected with the Lohia–Nehru controversies and because family domination emerged within the Congress especially after the crisis of the Emergency in 1975–77. Such exclusion is patently unfair to Jawaharlal Nehru, attacking whom has become a major organising point for Hindutva. Besides, to remain silent in the face of such attacks has the effect of denying the 20th century history of the Indian nation’s strivings and aspirations, a denial which, of course, the Hindutva forces ardently desire.

The crucial issue before the country is the social fascism associated with the ascendancy of the currently ruling forces and their associate organisations. Though it is right in this context to focus on the protection of civil liberties and on safeguards against a repeat of the Emergency, it is necessary to go beyond form and formalism. There is an undeclared social emergency in the country. Developments in rural western Uttar Pradesh in the run-up to the 2014 General Elections should have left no doubt on that score. The lives and property of members of the minority communities, Dalits and poor peasants are endangered. These forces operate with the support of elements within the Central and provincial state apparatus, the business world and affluent non-resident Indians. The fight against the malaise of corruption is only one part of the larger question of the accountability of power; the latter subsumes within itself struggles against governmental malfeasance and misfeasance in protecting citizens’ lives and welfare. Such accountability and protection is a solemn obligation on all political parties, a duty which Gandhi as well as Jawaharlal Nehru fully recognised.

Endnotes

- Acharya Narendra Deva, “Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru” in Acharya Narendra Deva, Socialism and the National Revolution [Yusuf Meherally (ed.)], Bombay, Padma Publications, 1946, pp. 203–204.

- Hartosh Bal, The Truth-teller in Sahgal (ed.), “Nehru’s India: Essays on the Maker of a Nation,” Speaking Tiger Publishing Pvt Ltd, New Delhi; 2015, p. 150.

- For some possible ideas in this context, see my article, “Three Outstanding Linguistic Issues: Some Suggestions”, Janata, June 26, 1994.

- How the composite insights of the socialist doer and thinker, Karpoori Thakur, and later of Kishan Patnaik were lost a decade or so later in the exclusively-caste-oriented framing of the reservation question in 1990–91 is pointed to in my article, “Moment of Truth for Janata Dal”, Economic and Political Weekly, June 29, 1991.

- I am unable to trace the reference for this very important comment by Surendra Mohan but it is most certainly there. In fact, I remember discussing Surendra Mohan’s article with him.

- Acharya Narendra Deva, “Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru” in Acharya Narendra Deva, Socialism and the National Revolution [Yusuf Meherally (ed.)], Bombay, Padma Publications, 1946, pp. 203–204.

- Ibid., pp. 206, 208.

- Kumar Ketkar in Sahgal (ed.), “Nehru’s India: Essays on the Maker of a Nation,” ibid., pp. 52-53.

- Quoted by Nayantara Sahgal in her Introduction to Sahgal (ed.), “Nehru’s India: Essays on the Maker of a Nation,” ibid.

- Cited by Aditya Mukherjee and Mridula Mukherjee in ibid., pp. 77–78.

- Air Commodore Jasjit Singh, China’s India War, 1962: Looking Back to See the Future, New Delhi, KW Publishers Pvt. Ltd., 2013; Nirupama Rao, Telling it on the Mountain: India and China and the Politics of History: 1949–1962, Occasional Paper No 73, Nehru Memorial Museum and Library, New Delhi, 2015.

- See The Hindustan Times, July 4, 1964, cited in Girja Shankar, Socialist Trends in the Indian National Movement, Meerut, Twenty-First Century Publishers, 1987, p. 294n.

(Anil Nauriya is a writer and an advocate of the Supreme Court.)