Peter Boyle

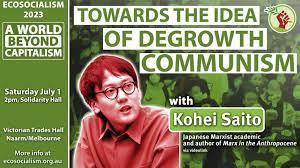

Even if Japanese Marxist Kohei Saito had not written Marx in the Anthropocene: Towards the Idea of Degrowth Communism, the left today would still need to take the idea of degrowth seriously. This is because, economist and anthropologist Jason Hickel explains, “while it’s possible to transition to 100 percent renewable energy, we cannot do it fast enough to stay under 1.5°C or 2°C if we continue to grow the global economy at existing rates.”

It’s not just reliance on fossil fuels that imperils the planet, but capitalism’s chronic pursuit of economic growth. Unlimited growth means more demand for energy. And more energy demand makes it more difficult to develop sufficient capacity for generating renewable energy in the short time left to avert catastrophic warming.

This is why Saito’s re-reading of Karl Marx’s life work is crucial for socialists today. As he argues, ecology wasn’t a secondary consideration for Marx but at the core of his analysis of capitalism. And as he neared the end of his life, Marx turned increasingly to the natural sciences and became deeply convinced that the endless growth associated with capitalism could not be harnessed for human or environmental purposes. Rather, as Saito details, Marx understood that communism would deliver both abundance and degrowth.

More than global warming

Today, environmental activists typically focus on global warming. But the problem is deeper than that. Scientists such as James Hansen and Paul Crutzen have identified a number of “planetary boundaries” beyond which disaster is all but certain. Climate change is one of these. However, tipping points also exist when it comes to the loss of biodiversity or forested land, ocean acidification, chemical pollution, ozone depletion, nitrogen and phosphorus loading in water and the depletion of fresh water.

For example, atmospheric carbon concentration should not breach 350 parts per million (ppm) if the climate is to remain stable — and we already crossed that boundary in 1990. Now, it is 420ppm. Similarly, disaster threatens if the proportion of the Earth’s land surface that is forested drops below 25 percent or if the extinction rate exceeds ten species per million per year.

From the deforestation of the Amazon to extinctions caused by climate-change driven bushfires in Australia, the root cause remains the same — unchecked economic expansion.

However much the evidence demands degrowth, the proposal nonetheless raises difficult political questions. For example, socialists in the developed and developing worlds are united in demanding improved living standards. And it’s hard to imagine a mass movement against capitalism gaining traction unless it can offer a better life.

These, however, are not insurmountable problems. As both Saito and Hickel argue, because of imperialism’s role in systematically passing ecological costs to the global South, economic growth needs to fall sharply in the wealthiest countries while continuing to grow in the global South.

But this does not mean that ordinary people in rich countries have to suffer a sharp drop in their quality of life. By radically restructuring the economy to prioritize social needs and ecological sustainability, it’s possible to improve life for the majority even while reducing production.

As Saito argued in Marx in the Anthropocene, later in life, as Marx deepened his research into political economy and natural science, this idea became more crucial to his vision of a post-capitalist society. However, it’s a perspective that was in part lost given that Marx did not live long enough to incorporate the analysis into planned but uncompleted later volumes of Capital. And this is not just conjecture. Saito builds his case on the basis of his deep knowledge of previously unpublished notebooks and writings that have now been published as part of the new complete works of Marx and Frederick Engels, the Marx-Engels-Gesamtausgabe (MEGA).

Marx, Saito writes, came to realize that the “capitalist development of technologies does not necessarily prepare a material foundation for post-capitalism.” This meant, as he continues, that

Marx not only regarded the “metabolic rifts” under capitalism as the inevitable consequence of the fatal distortion in the relationship between humans and nature but also highlighted the need for a qualitative transformation in social production in order to repair the deep chasm in the universal metabolism of nature.

The productive forces of capitalism

Saito identifies in Marx’s work four reasons why the productive forces developed under capitalism cannot be adopted in a post-capitalist ecosocialist society.

Firstly, because much technology is designed partly to subjugate and control workers, much of it is unfit for a non-exploitative society. Secondly, as Saito explains, “capitalist technologies are not suitable to the socialist requirement of reunifying ‘conception’ and ‘execution’ in the labour process.” This is to say, a socialist society must ensure that the utilization of technology is in accordance with the purpose for which it is designed, and that these work together for human and ecological ends.

Thirdly, according to Saito, Marx noted that “the capitalist development of productive forces undermines and even destroys the universal metabolism of nature.” This is to say, by disrupting and destroying whole ecosystems, capitalist development inhibits nature’s ability to renew itself. And fourthly, Saito argues that Marx predicted the development of technology that separates means and ends, as described above, would necessitate the rise of a “bureaucratic class.” This new class “would rule general social production instead of the capitalist class,” and “the alienated condition of the working class would basically remain the same.”

For these reasons, Saito argues, Marx started to question his earlier view that capitalism plays a progressive role by increasing society’s productive forces. As a result, as Saito contends, Marx was “inevitably compelled to challenge his own earlier progressive view of history.”

This perspective shift guided Marx’s work on planned but unfinished later volumes of Capital — he stepped up his study of both natural science and of pre-capitalist societies. And after 1868, this led Marx to another paradigm shift as he embraced what Saito and others now term degrowth communism.

According to this new perspective, Marx abandoned the idea that a communist society would simply appropriate the ecologically unsustainable abundance that capitalism now offers for a tiny minority. Instead, it would offer a “radical abundance of ‘communal/common wealth’.” According to Saito, Marx clarifies this in the Critique of the Gotha Program, defining it as “a non-consumerist way of life in a post-scarcity economy which realizes a safe and just society in the face of global ecological crisis in the Anthropocene.”

Indeed, if we read Marx’s late work in this light, it helps us understand his famous 1881 letter to Vera Zasulich, a Russian revolutionary. In it, Marx suggests that pre-modern communal land ownership models found in villages across the Russian empire might be transformed into collective, socialist ownership models. According to Saito, this letter ought to be “reinterpreted as the crystallization of his non-productivist and non-Eurocentric view of the future society,” and “should be characterized as degrowth communism.”

Essential work has lower ecological footprint

Saito argues that a socialist society would shift towards essential work that produces basic use-values, and as a consequence, economic growth will slow. An economy refashioned to serve social needs would have a dramatically lower ecological footprint, he adds, and the artificial scarcity that capitalism has manufactured ever since it destroyed the old commons can be overcome.

But is this true? There is research that suggests it is. Hickel’s study of UN data — cited in Less Is More — found that

The relationship between GDP and human welfare plays out on a saturation curve, with sharply diminishing returns: after a certain point, which high-income nations have long surpassed, more GDP does little to improve core social outcomes.

For example, Spain spends only $2,300 per person to deliver high-quality healthcare to everyone as a fundamental right and also boasts a life expectancy of 83.5 years, one of the highest in the world. Indeed Spain’s life expectancy is a full five years longer than that of the United States, where the private, for-profit system “sucks up an eye-watering $9,500 per person, while delivering lower life expectancy and worse health outcomes.” And much poorer Cuba has long enjoyed a higher life expectancy than the US because of its free and universal health care. During the COVID-19 pandemic this gap grew to three years.

Beyond this, Saito argues there are other good reasons why a post-capitalist society needs to radically refashion the economy. For example, under capitalism, more people are forced to do precarious “bullshit jobs,” a term he borrowed from the late anthropologist and anarchist activist David Graeber. Examples include telemarketers, parking and public transport ticket inspectors and most middle management. In addition to being meaningless, because they’re wasteful, the jobs contribute to environmental destruction, deepen inequality and worsen our mental health and quality of life.

On a broader level, degrowth communism would radically shorten the work week and liberate human creativity, sociality and social solidarity in the process. To explain, Saito notes that during the 20th and 21st centuries, rapid technological change led to increased productivity. And yet, work hours did not decline, again because capitalism necessitates constant growth.

Ultimately, however, Saito’s point is that we will only gain the freedom to make choices about what we produce collectively and how we do it by liberating the majority from the “despotism of capital.”

Against deterministic Marxism

These arguments mean that Saito makes common cause with a long line of Marxists — including Rosa Luxemburg, Leon Trotsky, Georg Lukács, Antonio Gramsci and others — who have opposed deterministic versions of Marxism. Although such theories of history run contrary to much of Marx’s work, both early and late, there are doubtless passages that lend support to historical determinism by claiming that capitalism will inevitably destroy itself.

For example, as Marx famously wrote in 1869 in A Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy,

At a certain stage of development, the material productive forces of society come into conflict with the existing relations of production … From forms of development of the productive forces these relations turn into their fetters. Then begins an era of social revolution. The changes in the economic foundation lead sooner or later to the transformation of the whole immense superstructure.

As Saito argues, it’s mistaken to read this as narrowly predicting that economic growth will flag, resulting in a big crisis and the necessary end of capitalism. To the contrary, “there is simply no empirical evidence that the pressure on profit rates due to the increasing costs of circulating capital will bring about an ‘epochal crisis’ any time soon.”

Indeed, capitalism may prove resilient to ecological catastrophe. As Saito explains,

it is necessary to realize net zero carbon emissions by 2050 to keep global warming within 1.5°C by 2100. When this line is crossed, various effects might combine, thereby reinforcing their destructive impact on a global scale, especially upon those who live in the Global South. However, capitalist societies in the Global North will not necessarily collapse.

Compared to more optimistic readings of Marx, Saito’s is sober. Arguably, however, the actual course of history since Marx’s time — which includes growing metabolic rifts — supports his outlook. And it’s why Marx’s late vision of degrowth communism may be a source of hope for our era of multiple, accelerating and overlapping crises.

(Peter Boyle is a socialist activist and writer for Green Left. Courtesy: Links International Journal of Socialist Renewal.)

Critical Comments on Kohei Saito’s View of ‘Degrowth Communism’

David Schwartzman

Peter Boyle’s review of Kohei Saito’s book Marx in the Anthropocene: Towards the Idea of Degrowth Communism provides an excellent account of its main points.

My critique can be summed up as: “Yes to degrowth communism” but likewise “Yes to good growth ecosocialism” to get there.

In the ecosocialist transition to degrowth communism that Boyle points to, the process of radically shortening the work week and liberating human creativity, sociality and social solidarity would begin to unfold.

Boyle quotes Hickel: “while it’s possible to transition to 100 percent renewable energy, we cannot do it fast enough to stay under 1.5°C or 2°C if we continue to grow the global economy at existing rates.”

A transition of this kind means that fossil fuels should be terminated faster than renewables can be created to replace them. But Hickel does not say what needs to grow — besides renewable energy supplies — and what needs to degrow, in this transition. Deconstructing economic growth into its components is essential to answer this question.

The degrowth brand was challenged by Josef Baum a decade ago:

“Walter Hollitscher, an Austrian materialist philosopher maintained, in discussions occurring in the late 1970s, that the only thing which should definitely grow is the satisfaction of needs. Basically, from a socio-ecological point of view the question of growth or de-growth is simple: there cannot be a yes or no answer. Some flows, stock, and activities should grow; others should not grow but decrease, for example, the production of weapons. It does not seem useful to use “de-growth” without indicating what should decrease, because the general use of the notion “de-growth” easily can easily also be understood as an undifferentiated attack on the standard of living and livelihood of many groups of people, especially broad low-income sectors of society.”[1]

I have critiqued degrowth from a similar position.[2] But Saito opposes any form of economic growth, even in an ecosocialist, post-capitalist regime: “Ecosocialism does not exclude the possibility of pursuing further sustainable economic growth once capitalist production is overcome, but degrowth communism maintains that growth is not sustainable nor desirable even in socialism.” (p. 209)

So it is disappointing since we are still embedded in fossil capitalism that Saito does not systematically deconstruct the degrowth discourse with these distinctions in mind, good versus bad growth in the context of a strategy to reach the goal of degrowth communism..

With the driver being multidimensional class struggle increasingly informed by an ecosocialist agenda under capitalism, ecosocialists commonly support vigorous degrowth of wasteful consumption particularly of the 1%, reliance on cars (even electric), mega-mansions, and especially the military industrial fossil fuel complex, coupled with the growth of renewable energy supplies, free electrified public transit, green affordable housing, agroecologies providing organic food, first rate healthcare and education of all, social governance of the economy. In other words, reaching for the ecosocialist horizon moving to a postcapitalist demilitarized world at peace.

Saito gives us a penetrating exegesis of Marx’s writings, especially of the late Marx, providing profound insights, reinforcing Malm’s critique of hybridism, with a valuable critique of the left “accelerationists” who expect technology by itself to bring the world communism. But Saito neglects to analyze the degrowth literature and its critique from the left.

For example, I am cited: “Many still believe that Marxism and degrowth are incompatible (Schwartzman 1996),” (pp. 209-210), But I don’t even mention degrowth, nor its incompatibility with Marxism in my 1996 paper,[3] and unfortunately Saito passes on any discussion of Georgescu-Roegen’s thermodynamics, which is foundational to degrowth discourse.

I assume that Saito may be referring to my more recent articles and books — e.g. our critique of Kallis (2017).[4] He cites Hickel and Kallis,[5] but not our critique.[6]

Instead we find Saito saying: “Technological progress can push limits back to some extent, but entropy increases, available energy decreases and natural resources get exhausted. These are objective facts that are independent of social relations and human will.” (p. 113)

But in a 100 percent global renewable energy world this entropy debt is paid to space as waste heat without contributing to global warming as now with 80 percent of energy derived from fossil fuel consumption. Further this renewable energy supply, greater than present primary energy consumption, can power a global circular economy necessary for degrowth communism, but this energy infrastructure must be created with real growth of this sector in the physical economy.

In this transition, starting under capitalism, the capacity for climate mitigation and adaptation along with elimination of energy poverty afflicting the global South must be created in the form of mainly wind and solar energy supplies.[7] Saito does not confront this challenge.

He quotes John Bellamy Foster:

“Society, particularly in rich countries, must move towards a steady-state economy, which requires a shift to an economy without net capital formation, one that stays within the solar budget. Development, particularly in the rich economies, must assume a new form: qualitative, collective, and cultural — emphasizing sustainable human development in harmony with Marx’s original view of socialism.”(p. 210) [8]

But rich countries, having the historic responsibility for generating dangerous climate change from their consumption of fossil fuels with the greatest impacts on the global South, now must be held accountable to finance and help implement the necessary wind/solar energy infrastructure especially in the global South, as well as converting their own physical economies to green cities, electrified public transit, agroecologies, etc, dismantling the military industrial fossil fuel complex.

Indeed, Saito recognizes the important role of renewable energy: “As a solution to climate crisis, solar panel and EVs are essential, but the associated battery technology is resource intensive, especially with regard to rare metals.” (p. 41)

But he does not recognize that there are solutions to address the serious challenge of extractivism in a robust wind/solar energy transition, namely using this energy supply for recycling metals including the huge supplies now embedded in the fossil fuel and military infrastructures in a circular physical economy, as well as substituting common elements for rarer ones (e.g., sodium for lithium in batteries) for renewable and energy storage technologies.[9]

Degrowth Communism is close in concept to Solar Communism both with a steady-state physical economy, realizing a 21st century update of Marx, “From each according to her ability, to each according to her needs” with her referring to both humans and nature. This corresponds to what I recently labeled as the future epoch of Solarcommunicene.[10] Saito’s book hopefully will help promote this future.

Notes

[1] Josef Baum, “In Search for a (New) Compass – How to Measure Social Progress, Wealth and Sustainability?” Transform! European journal for alternative thinking and political dialogue, 2011.

[2] David Schwartzman, “ A Critique of Degrowth and Its Politics,” Capitalism Nature Socialism, 2012.

[3] David Schwartzman, “Solar Communism.”

[4] G. Kallis, “Socialism Without Growth,” Capitalism Nature Socialism (2017); D. Schwartzman and S Engel Di Mauro “A Response to Giorgios Kallis’ Notions of Socialism and Growth,” Capitalism Nature Socialism, (2019)

[5] J. Hickel, ‘Degrowth: A Theory of Radical Abundance’. Real-World Economic Review, (2019); G. Kallis, “Socialism Without Growth.”

[6] David Schwartzman, “Solar Communism.”; D. Schwartzman, “A Critique of Degrowth”; D. Schwartzman, “Degrowth in a renewable energy transition?”

[7] https://climateandcapitalism.com/2022/01/05/a-critique-of-degrowth/; http://theearthisnotforsale.org/dschwartzman_exeter42022.pdf

[8] J.B. Foster, “Marxism and Ecology: Common Fonts of a Great Transformation,” Monthly Review (2015).

[9] climateandcapitalism.com/2022/01/05/a-critique-of-degrowth/

[10] David Schwartzman, “An Ecosocialist Perspective on Gaia 2.0,” Capitalism Nature Socialism (2020).

[David Schwartzman is Professor Emeritus (Biology) at Howard University, and co-author of ‘The Earth is Not For Sale: A Path Out of Fossil Capitalism to the Other World That is Still Possible’ (World Scientific, 2019). Courtesy: Climate and Capitalism, an ecosocialist journal, edited by Ian Angus.]